Читать книгу WG Grace - Robert Low - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 · INTRODUCTION

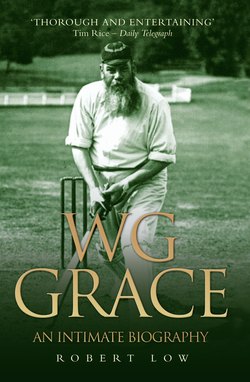

ОглавлениеMUCH was written about W.G. Grace, who was born on 18 July 1848, during his full and active lifetime and much has been written since. We have an image of him: a huge, bulky bearded man, glowering at the camera from beneath a striped cap which looks faintly ridiculous on such a massive head. Or perhaps posing at the crease, in one of those stilted Victorian photographs. Or preparing to bowl, still with his cap on, his arm much lower than anything you would see today. The image is that of a man who was very far from being an athlete, yet everyone who knows anything about cricket knows this: W.G. Grace was the greatest cricketer England has ever seen.

What else could they tell you? After all, cricket followers can recite statistics and relate them to individuals at the drop of a floppy white hat. Len Hutton? He scored 364 against Australia in 1938, a world record which stood for nearly thirty years. Jack Hobbs? Most centuries – 197, to be precise. Ian Botham? In 1981, his two whirlwind centuries against Australia turned the tide and won back the Ashes. Jim Laker? He took a record nineteen wickets in a Test match in 1956. I wrote those down without consulting a single reference book, and I could do the same for many more players, both English and overseas.

Before I embarked on this biography of W.G. Grace, I could not have told you anything much about him except that he was a large, corpulent man with a beard, a doctor of medicine, an all-rounder who dominated the game of cricket in his day. Above all, he was a character, a bit of a rogue, a batsman who hated to leave the crease, a player who hated to lose, a man who bent the rules to suit himself. The one story everyone knows about him is of his dismissive retort to an umpire who had just attempted to give him out: ‘They’ve come to see me bat, not to see you umpire.’

As I set about the task of retelling his life, I frequently asked myself what the point of it was. Did the world need a new biography? Plenty had been written, some during his life, a massive, rambling Memorial Biography compiled by the game’s great and good soon after his death in 1915, several at regular intervals since, notably by Bernard Darwin, better known as the father figure of modern golf writing, in 1934, by A.A. Thompson (my own favourite) in 1957, and Eric Midwinter, academic, social historian and cricket buff, whose blend of interests produced an interesting portrait in 1981.

My frequent doubts would be offset by the number of people who, on finding out my project, (a) declared that it sounded a very interesting idea, and (b) revealed that they knew absolutely nothing about W.G. beyond the sort of sketchy brushstrokes I have mentioned above. It encouraged me to plough on, in the growing belief not only that Grace’s life was a fascinating one but that it deserved to be told again, and perhaps reinterpreted, for a new generation. And the more I looked into his life, the less like the usual caricature it appeared to be.

Beyond a Boundary by C.L.R. James, the great West Indian writer on cricket, history and politics, should be required reading for anyone interested in the game and how it developed in the Caribbean. A Marxist, but utterly devoid of the dogmatism normally associated with people to whom that adjective is applied, James devoted two fascinating chapters of Beyond a Boundary to W.G. and his key place in the Victorian era. Most of what he wrote is brilliantly perceptive and reads as freshly as if written yesterday. His central thesis was that Grace was ‘a typical representative of the pre-Victorian Age’ who nevertheless came to be one of a trio who symbolised Victorian culture, the others being Thomas Arnold, the great headmaster of Rugby, and Thomas Hughes, author of Tom Brown’s Schooldays. Yet you would search through the history books of the period in vain for any mention of Grace, an omission which James deplored.

Viewing him in purely cricketing terms, he also saw Grace as the founder of modern batting, and the man who almost single-handed and ‘by modern scientific method … lifted cricket from a more or less casual pastime into the national institution which it rapidly became’. What are the missing words in that sentence? ‘This pre-Victorian’ – James was infatuated with the notion of Grace springing from a pre-industrial Arcadia and somehow rising above the Victorian hurly-burly to impose his will upon his sport.

While I am convinced by most of James’s elegant proposition, I cannot see Grace as a pre-Victorian, and not only because Victoria had already been Queen for eleven years before he was born. Neville Cardus was surely right to have characterised him as the archetypal Eminent Victorian, perhaps the one public figure who was instantly recognisable to the common man. For my part, the more I have immersed myself in Grace’s life, the more modern he seems to be. The overriding impression he leaves is that he would have been as successful in the late twentieth century as he was in the equivalent period of the nineteenth.

There were always two sides to Grace. He may have been an amateur, in name at least and certainly by nature, but in reality he was the ultimate professional in every respect, almost from the beginning. He was reared to be a cricketer, by a family whose obsession the game was – two of his brothers were among the finest players of the age alongside him, his father helped to shape the game in the West Country and even his mother was devoted to the game and the fortunes of her offspring.

Throughout his long career he earned more money from the game than any of the so-called professionals with whom he played. Indeed, so bitter did they become at this that five of them finally threatened to go on strike over the issue before the Oval Test match of 1896, and two declined to play when their demands were refused. Although much is made of his simultaneous medical career, he was only too glad to abandon it in his early fifties, just when he might have been thought to be about to settle down to the life of a full-time doctor, in order to devote himself entirely to cricket, as secretary-captain of the new London County Club.

Equally, there were two faces of W.G., the cricketer. There is the familiar, bulky figure to which I have already referred and which still dominates our image of him – but there is an altogether different face which, I believe, has become neglected and obscured by the later one. This one is the Grace of his late teens and twenties: a tall, slim, graceful, athletic figure, whose long black beard contained not a fleck of grey and who rewrote the record books in the decade or so between the mid-1860s and mid-1870s. This Grace resembled a fierce young prophet, or a Zionist pioneer. He slightly resembled the young Theodor Herzl, who imposed his own will on a different field of play.

He is as different from the older Grace as the young Botham of 1981 was from the man whose international career was virtually over only a decade later. Incidentally, how Grace would have loved to have played with Botham! And what high jinks that pair might have got up to after play was over for the day. But whereas Botham was effectively finished as a cricketer by his mid-thirties, W.G. went on and on, his career bursting into life again in his late forties like one of those ancient plants that suddenly and unexpectedly produce a glorious flower when it was thought to be incapable of doing so again.

Cricketers who play on well into their forties at the highest level are not unknown in the modern age. One thinks of Cyril Washbrook, gloriously recalled to the England colours at the age of forty-two and responding with 98, of Bill Alley saving his best until the late autumn of his career when he scored more than 3,000 runs in one season (1961), also aged forty-two. In our own era, Graham Gooch is also going strong at forty-three and in 1996 passed W.G.’s mark of 1 first-class centuries. But what distinguishes Grace from anyone else is that he provides a bridge from the old world to the new. In 1863, at the age of fifteen, he played for a Bristol Twenty-Two against William Clarke’s professional circus, long before there was such a thing as a county championship. In 1899, at the age of nearly fifty-one, he was opening the batting for England against Australia with C.B. Fry and matching the arch-Corinthian stroke for stroke, if not in fleetness of foot between the wickets. He played with and against the ageing John Lillywhite in the 1860s and the young Jack Hobbs at the turn of the century.

In between, he rewrote – or perhaps I should say wrote, for there was nothing much before him – the record books. The statistics are awesome. He scored 54,211 first-class runs in a career that lasted an incredible forty-three years, from 1865 to 1908 (the exact number of runs is disputed by cricket statisticians, some of whom appear to have dedicated the best part of their lives to trying to trace every run he scored). Only four batsmen have made more – Jack Hobbs (61,237), Frank Woolley, Percy Hendren and Phil Mead. Of later players, Walter Hammond had a total of 50,551, Herbert Sutcliffe 50,138, Geoffrey Boycott 48,426 and Graham Gooch had accumulated 44,472 by the end of 1996. But statistics tell only part of the story. In the first half of his career, Grace played on pitches which were often atrocious by modern standards, when scores were far lower than they became from the 1880s onwards. In those circumstances, his achievements were remarkable. For instance, in 1871 he scored 2,739 first-class runs, the first man to clear 2,000 in a season.

Compared with Grace in that season, only one other batsman topped 1,000 (Harry Jupp, with 1,068). In 1873, W.G. made 1,805, when nobody else could manage 1,000 (the dogged Jupp failed by 4). In his great year of 1876, W.G. made 2,622, including 839 in eight days, a spell which included two triple-centuries. Nobody had ever managed even one before and only one other batsman scored more than 1,000 that summer. The previous month W.G. had scored 400 not out against twenty-two fielders at Grimsby. Yet nineteen years later, in 1895, he was still good enough to become the first batsman to score 1,000 first-class runs in May and to rattle up 2,346 runs in the season. How many might he have scored on the shirt-front wickets of modern times, or if he had toured abroad more than three times (twice to Australia, once to Canada and the USA)?

He also made more than 45,000 runs in club and other minor fixtures. Did he score more than 100,000 runs in all forms of cricket? Some believe he falls short of the magic figure by a tantalising few but, just as I like to think of Mallory and Irving disappearing into the clouds just short of the summit of Everest but getting to the top before perishing on the way down, so I like to think of W.G. having reached his 100,000, despite what the dry race of statisticians says.

He was a highly effective bowler, taking 2,808 first-class wickets, first as a brisk round-arm seamer, then slowing down with age to become a purveyor of gentle leg-breaks which lured successive generations of batsmen to a destruction they all thought impossible against such soft stuff – and he diddled out a further 4,500 or so in minor cricket. But statistics, while imposing, tell less than half the story. For W.G. was cricket for the Victorian public, the most recognisable face in the country along with Gladstone (Monsignor Ronald Knox playfully suggested they were one and the same person).

His participation in a match was guaranteed to add thousands to the gate. If the news spread round London that he was batting at Lord’s or The Oval, offices would empty and the cabs stream up the roads to St John’s Wood or Kennington. If he was playing at Trent Bridge, Old Trafford or Sheffield, the workers would leave factory or furnace to walk miles for a sight of him batting. And how rarely would he let them down. Of plain country stock himself, he had an instinctive empathy with the common man. The spontaneous displays of affection, the crowds spilling over the ropes to chase him to the pavilion at the end of a great innings, or merely the day’s play, were evidence of his huge popularity. Twice national testimonials were organised on his behalf, once by the MCC, once by the Daily Telegraph, and on both occasions the public was unstinting in its generosity to a man who had already done well out of the game financially, although he was never one to turn down money.

This sense of comradeship with ordinary people was most marked in his work as a doctor in Bristol. There are many stories of his kindness to poor people, of his little gifts to those in trouble and his efforts to get them help or work. But he was no saint: he had a violent temper, which it was easy to provoke. In 1889 he battered a youth with a cricket stump after the lad had the temerity to ignore W.G.’s orders not to practise on the new county ground at Bristol, and was fortunate to escape legal proceedings. In the event, an apology was enough to settle the matter. He had to apologise in similar fashion to settle a huge row with the Australian touring side of 1878 whom he had outraged by kidnapping Billy Midwinter, the Australian player also registered with Gloucestershire, from Lord’s and taking him off to The Oval for a county match on 20 June. That was W.G. all over – quick to rouse, and usually quick to make up, or regret his actions. The most obvious example is his resignation from the Gloucestershire captaincy in 1899 with a withering letter of contempt and hatred for the committee who, he believed, had forced him to take such a step unnecessarily. But he regretted it ever afterwards, and was delighted when fences were mended a few years later.

Indeed, he was often pathetically reluctant to give offence or to dredge up old quarrels. His books of memoirs are utterly devoid of contentious material, and it is difficult to believe they could have any connection with the man who had been involved in so many confrontations on and off the field in England and Australia. It was almost as if he preferred to believe they had never happened. In old age, he was even unwilling to get involved in nominating his greatest XI, a harmless exercise if ever there was one, for fear of giving offence to someone. Behind that brooding, off-putting facade there may have lurked a rather uncertain personality.

He could also be tolerance itself, especially if children were involved. When he arrived at the county ground, Bristol, one morning in 1896 for a match starting at 11.30 a.m., there was already a crowd of about thirty boys waiting outside. He opened the door himself and the boys asked if they could pay him. He let them in and told them to go back and pay when the gates opened. As he walked off, he asked his companion and team-mate, Robert Price, ‘Think they’ll come back and pay?’ Price replied, ‘I don’t think they will.’

‘No, I shouldn’t,’ replied W.G., laughing.

When a visitor to Bristol paid for his family to get into the ground at Clifton under the mistaken impression it was Clifton Zoo, the gatekeeper refused to give him his money back. Spotting W.G.’s unmistakable face, the man went up to him and told him of his error. W.G. took him back to the gate, made the keeper refund him and pointed out the correct way to get to the zoo.

As he grew older he became more and more autocratic. His family virtually founded Gloucestershire County Cricket Club and were instrumental in making it an instant success and leading it to a glorious first decade of existence never since equalled. He captained the team for twenty-nine years but would not change his selection policy or his way of doing things when the county hit bad times in the late 1880s and early 1890s. The subsequent parting of the ways was inevitable, for he was never a man to compromise.

Not only did he quit Gloucestershire County Cricket Club, he left the county of his birth, and the practice of medicine, for ever and moved to London. The abruptness of his departure is intriguing. Did he ever really enjoy being a doctor? Did he perhaps go into medicine out of a sense of family duty? His father and three older brothers were doctors and it seems to have been considered inevitable that W.G. would follow suit. Whether he was ever consulted about it is another matter.

His medical studies took him the best part of a decade to complete, which is hardly surprising given that at the same time he was in his prime as a cricketer and made two overseas tours. But even so it does not speak of great aptitude for the work. He practised medicine in Bristol for nearly two decades, mainly in the winter, for he continued to play cricket during the summers with undiminished enthusiasm, and was greatly loved by his patients. But at the age of fifty-one he gave it up at short notice and never went back to it.

This was premature by any standards. His father and brothers, for example, practised medicine almost until their dying days. In various memoirs, W.G. never wrote a word about his medical work and does not seem to have missed it at all, particularly once his financial future was secure, thanks to his second testimonial. Perhaps he went along with the study of medicine in the 1870s out of respect for the memory of his father, Dr Henry Grace, who died in 1871, and felt free to abandon a doctor’s labours after the death of his eldest brother, Henry junior, in 1895.

He was not a complicated man. Like most of the Grace brothers, he adored practical jokes and schoolboy japes, even in his fifties. His idea of a lark was to suggest to his fellow-players staying at the Grand Hotel, Bournemouth, to race up the stairs to the top of the hotel and back, the last man to stand drinks all round – and this at one o’clock in the morning. He took part, naturally, and did not have to pay for the round. Then they did it all over again, to the consternation of the other guests, who by now thought the hotel must be on fire. As several of his contemporaries noted, he was really just an overgrown schoolboy. Indeed, he was never happier than in the company of children. One of his granddaughters remembered sitting on his knee and tying ribbons in his beard, to his huge amusement.

He left Bristol for ever in 1899 but there were many in the city nearly half a century later in the 1930s who could still remember Dr Grace on his rounds putting down his bag and joining in a snowball fight with the local boys, or an impromptu game of cricket. He would round up a few youths to bowl at him in his garden or before an innings on the county ground, always tipping them generously. For while he was notorious for demanding and getting what he thought he was worth as a cricketer he was equally free in dispensing his money to anyone, young or old, who did him a favour. When a youth found his purse in the street and took it to his surgery, W.G. gave him the purse and all the money in it, which was enough to buy the lad a new suit.

He seems to have spent his life in perpetual motion. When he wasn’t playing cricket or attending to his patients, he was out following the beagles or, in later life, playing golf or bowls. He adored beagling, a recreation he pursued all his life (he had to give up riding to hounds when he got too heavy for a horse). His stamina was remarkable and so was his strength, as one Gloucestershire farmer discovered when he tried to block W.G. from pursuing the beagles into his fields. W.G. simply picked up the man, tucked him under his arm and strode across his land, depositing him on the other side with a threat to smack his bottom if he misbehaved himself further. When another farmer rejoiced at the sight of W.G. falling headlong into a ditch as he raced after the dogs, W.G. got up, grabbed him and sat him down in the water too. ‘He picked me up as if I’d been a new-born baby,’ the farmer is said to have remarked wonderingly when told the identity of his huge assailant.

Such stories are all part of the Grace legend, and there are a thousand such anecdotes about his cricketing life which have gone into the game’s folklore. Many of them involve Tom Emmett, the doughty Yorkshire left-arm seam bowler who was involved in many a long battle with W.G. ‘He ought to have a littler bat,’ was his comment during one epic innings. Another left-armer who came in for a lot of punishment from W.G. was Nottinghamshire’s James Shaw, who made the immortal remark: ‘I puts ’em where I likes, and he puts ’em where he likes.’

The commonest perception of W.G., which persists to this day, is that he was a cheat, that he bent the rules to suit himself, and would simply ignore an umpire’s decision if he did not agree with it. ‘He would stretch the laws of cricket uncommonly taut in his own favour,’ wrote Lord Hawke, ‘but nobody bore him a grudge.’ Whether W.G. behaved very differently from anybody else playing then or now is a moot point. I was writing some of this book to the accompaniment of the radio commentary on the climax of the first Test between Zimbabwe and England in December 1996, when Zimbabwe deliberately bowled wide to prevent the England batsmen from scoring the last few vital runs. I have no doubt that had W.G. been captaining the fielding side in such a situation he would have ordered his bowlers to behave in a similar fashion.

He played to win, although he could accept defeat gracefully. He undoubtedly tried to intimidate umpires into giving marginal decisions in his favour but, again as I write, the England team in Zimbabwe has just been warned by the match referee for that very offence. When Gloucestershire played Essex at Leyton in 1898, W.G. infuriated the Essex fielders as the game built up towards a tight finish by refusing to accept the umpire’s initial verdict of ‘out’ for what he thought was a bump-ball return catch. On that occasion, the umpire backed down, but just as frequently umpires did not, sending W.G. on his way despite his grumbles. Once he enquired, as he left the wicket, which leg the umpire thought the ball had struck for an lbw decision. ‘Never mind which leg,’ replied the umpire. ‘I’ve given you out and out you’ve got to go.’

To another umpire who had also given him out leg before, W.G. complained, ‘I played that ball.’

‘Yes,’ retorted the umpire, ‘but it was after it had hit your leg.’

In these days the sports pages are full of batsmen who never touched the ball but were given out caught behind, or off bat and pad at forward-short-leg, and often we are none the wiser after watching the television replay half-a-dozen times.

So, while W.G. may frequently have stretched the laws as far as he could, the idea that he invariably disregarded the umpire’s verdict if he did not agree with it is an exaggeration. He once prevented a Gloucestershire batsman from leaving the pavilion to go out to the wicket at Bristol because he believed the last man out, Gilbert Jessop, had not been fairly caught on the boundary. The game was held up for half an hour while the argument raged but the umpires had their way in the end.

W.G. was essentially a cricketer who liked to win and occasionally crossed the barrier between fair and foul play in tight situations, like many others before and since. He was involved in a number of notorious incidents in first-class cricket, such as when he ran out the Australian batsman Sammy Jones in the legendary match at The Oval in 1882 when Jones wandered up the pitch to do a spot of ‘gardening’. Most people – including the batsman – thought the ball was dead but the umpire bowed to W.G.’s appeal.

Tony Greig did something very similar to Alvin Kallicharran in 1974, and the umpire agreed with him too. Such was the outcry that the appeal was withdrawn and the West Indian reinstated, but when people think of Greig today they don’t think of him primarily as a cheat but as occasionally over-enthusiastic for the best motives. (Incidentally, had Kerry Packer existed in W.G.’s day, he would have been strongly tempted to throw in his lot with Packer, as Greig did, for W.G. was always keen on money. He would have made a great limited-overs player too.)

Like players today, he behaved worse than normally if he thought the standard of umpiring was low, as it probably was on his two tours of Australia where he repeatedly took umbrage at the umpires’ decisions, and thereby earned the hostility of press and public, though interestingly not of the Australian players. They knew a tough competitor when they saw one, and probably didn’t think much of their own officials either.

Nothing W.G. got up to in Australia was anything like as bad as the row between the England captain Mike Gatting and the local umpire Shakoor Rana in Pakistan in 1987 which helped to sour cricketing relations between the two countries for years.

Many of the stories about W.G. and umpires stem from club matches where nothing was at stake and where the crowd undoubtedly wanted to see the legendary figure in action. He went out to open the innings in a charity match, attended by a large and expectant crowd, only to see the second ball remove the off bail. W.G. bent down, picked it up and replaced it, saying to the wicketkeeper in his inimitable Gloucestershire accent, ‘Strong wind today, Jarge.’ No one queried his action and he went on to hit 142 – which is what everyone had hoped to see.

His contemporaries had no doubt about his stature. Those two cricketing peers who dominated the councils of the Victorian game, Lords Hawke and Harris, produced very similar verdicts on him. ‘As a cricketer,’ wrote Hawke,

I do not hesitate to say that not only was he the greatest that ever lived, but also the greatest that ever can be, because no future batsman will ever have to play on the bad wickets on which he made his mark and proved himself so immeasurably superior to all his contemporaries.

According to Harris,

he was … always a most genial, even-tempered, considerate companion and of all the many cricketers I have ever known the kindest as well as the best. He was ever ready with an encouraging word for the novice, and a compassionate one for the man who had made a mistake … It is difficult to believe that a combination so remarkable of health, activity, power, eye, hand, devotion and opportunity will ever present itself again.

There is much more anecdotal evidence about his kindness to young players and modesty about his own achievements.

If he had a weakness, it was as a captain. While he was a dab hand at enticing a batsman out with a crafty bit of field placing, he had a tendency to let things drift along when imagination and daring were called for. He was no innovator, but an instinctive conservative, and he brooked no opposition to his way of doing things. His record was patchy. He led Gloucestershire with great success in the first years of the county’s official existence but that was due more to his own overwhelming dominance with bat and ball, ably backed up by his brothers E.M. and G.F. The county’s fortunes declined and W.G. failed to bring on enough new players to restore it to its previous eminence.

But of his own playing ability there will never be any doubt. In our century, Gary Sobers was a purer all-rounder and Don Bradman a greater run-getter, although there are some interesting parallels between Bradman and Grace. Both were country boys who displayed a fierce dedication from a very young age, while their adult play was characterised by enormous patience and discipline. Neither was a stylist; instead, they were brutally effective, deriving an almost sadistic pleasure from reducing a bowling attack to rubble. Bradman’s career batting figures (first-class average: 95.14, Test average 99.94) were far superior to Grace’s but he played on much better pitches. Perhaps the greatest similarity between them was that they represented more than cricket to the common man in his own country. Bradman was the personification of an Australia emerging from the dominance of its colonial master, Grace the hero to the working class of industrial Victorian England.

W.G.’s abiding legacy, however, is that no single cricketer has since dominated the game so totally as he did for more than thirty years. English cricket these days could do with someone possessing one tenth of his talent, discipline and will to win.