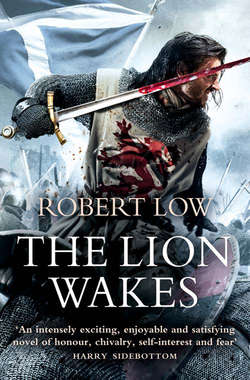

Читать книгу The Lion Wakes - Robert Low - Страница 10

ОглавлениеChapter Two

Douglas Castle, later that day

Vigil of St Brendan the Voyager, May 1297

They waited for the Lady, knights, servants, hounds, huntsmen and all, milling madly as they circled horses already excited. The dogs strained at the leashes and leaped and turned, so that the hound-boys, cursing, had to untangle the leashes to load them in their wooden cages on the carts.

Gib had the two great deerhounds like statues on either side of him and turned to sneer at Dog Boy. The Berner had given the stranger’s dogs into Gib’s care because Dog Boy was less than nothing and now Gib thought himself above all the sweat and confusion and that the two great hounds leashed in either fist were stone-patient because of him. Dog Boy knew better, knew that it was the presence of the big Tod’s Wattie nearby.

Hal frowned, because the deerhounds, if they had chosen, could leap into the mad affray and four men would not hold them if their blood was up, never mind a tall, scowling boy with the beginning of muscle and a round face fringed with sandy hair. With his lashes and brows and snub nose, it all contrived to make him look like an annoyed piglet; he was not the one with the charm over the deerhounds and Hal knew the Berner had arranged this deliberately, as a snub, or to huff and puff up his authority.

The one with the hound-skill – Hal sought him out, caught his breath at the stillness, the stitched fury in the hem of his lips, the violet dark under his hooded eyes and the dags of black hair. Darker than Johnnie, he thought . . . as he had thought last night, the lad had the colouring and look of Jamie and might well be one of The Hardy’s byblows, handed in to the French hound-master of Douglas for keeping. Hal switched his gaze to fasten on Berner Philippe, standing on the fringes of the maelstrom and directing his underlings with short barks of French.

The weight of those eyes brought the Berner’s head up and he found the grey stare of the Lothian man, blanched, flushed and looked away, feeling anger and . . . yes, fear. He knew this Sientcler had been given the Dog Boy by the Lady, passed to him without so much as a ‘by your leave, Berner’, and that had rankled.

When told – told, by God’s Wounds – that the Dog Boy would look after the deerhounds he had decided, obstinately, to hand them to Gib. It was, he knew, no more than a cocked leg marking his territory – all dogs in Douglas were his responsibility, no matter if they were visitors or not – and he did not like being dictated to by some minor lordling of the Sientclers, who all thought themselves far too fine for ordinary folk.

He liked less the feel of that skewering stare on him, all the same, busied himself with leashes and orders, all the time feeling the grey eyes on him, like an itch he could not scratch.

Buchan sat Bradacus expertly and fumed with a false smile. The hunt had been the Bruce’s idea at table the night before and he had spent all night twisting the sense of it to try to the Bruce advantage in it. Short of a plot to kill him from a covert, he had failed to unravel it, but since he’d had nothing else to occupy him the time wasted had scarcely mattered. The bitterness of that welled up with last night’s brawn in mustard, a nauseous gas that tasted as vile as his marriage to the MacDuff bitch.

It had seemed an advantageous match, to him and the MacDuff of Fife. Yet Isabel’s own kin, bywords for greed and viciousness, had slain her father, which was no great incentive for joing the family. Even at the handseling of it, Red John Comyn of Badenoch had tilted his head to one side and smeared a twisted grin on his face.

‘I hope the lands are worth it, cousin,’ he had said savagely to Buchan, ‘for ye’ll be sleeping with a she-wolf to own them.’

Buchan shivered at the claw-nailed memory of the marriage night, when he had broken into Isabel MacDuff. He had done it since – every time she was returned from her wanderings – and it was now part of the bit, as much as lock, key and forbiddings to make her a dutiful wife, fit for the title of Countess of Buchan. That and the getting of an heir, which she had so far failed to do; Buchan was still not sure whether she used wile to prevent it or was barren.

Now here she was, supposedly ridden to Douglas on an innocent visit and using Bradacus’ stablemate, Balius, to do it. Christ’s Wounds, it was bad enough that she was unchaperoned – though she claimed such from the Douglas woman – but without so much as a servant and riding a prime Andalusian warhorse in a country lurking with brigands was beyond apology.

She could be dead and the horse a rickle of chewed bones . . . he did not know whether he desired the first more than he feared the second, but here she was, snugged up in a tower, refusing him his rights while he languished in his striped panoply in the outer ward, too conscious of his dignity to make a fuss over it.

That dropped the measure of her closer to the nunnery he was considering. He was wondering, too, if she and Bruce . . . He shook that thought away. He did not think she would dare – but he had set Malise to scout it out.

Now he sat and fretted, waiting for her to appear so they could begin this accursed hunt, though if matters went as well as the plans laid, the Gordian knot of the Bruces would be cut. Preferably, he thought moodily, before Bruce’s secret blade.

Which, of course, was why he and his men chosen for this hunt were armed as if for war, in maille and blazoned surcoats; he noted that the Bruce was resplendant in chevroned jupon, bareheaded and smiling at the warbling attempts of young Jamie Douglas to sing and play while controlling a restive mount. Yet he had men with him, unmarked by Carrick livery so that no-one could be sure who they belonged to.

He looked them over; well armed and mounted on decent garrons. They looked like they had bitten hard on life and broken no teeth – none more so than their leader, the young lord from Herdmanston.

Hal felt the eyes on him and turned to where the Earl sat on his great, sweating destrier, swathed in a black, marten-trimmed cloak and wearing maille under it. The face framed by a quilted arming cap was broad, had been handsome before the fat had colonised extra chins, was clean-shaven and sweating pink as a baby’s backside.

The Earl of Buchan was a dozen years older than Bruce, but what advantage in strength that gave the younger man was offset, Hal thought, by the cunning concealed in those hooded Comyn eyes.

Buchan acknowledged the Herdmanston’s polite neck-bow with one of his own. Bradacus pawed grass and snorted, making Buchan pat him idly, feeling the sweat-slick of his neck even through the leather glove.

He should have begged a palfrey instead of riding a destrier to a hunt, he thought moodily, but could not bring himself to beg for anything from the Douglases or Bruces. Now a good 25 merks of prime warhorse was foundering – not to mention the one his wife had appropriated, and he was not sure whether he fretted more for her taking a warhorse on a jaunt or for her clear, rolling-eyed flirting with Bruce at table the night before.

Brawn in mustard and a casserole of wheat berries, pigeon, mushrooms, carrots, onions and leaves – violet leaves and lilac flowers, the Lady Douglas had said proudly. With rose petals. Buchan could still feel the pressure of it in his bowels and had been farting as badly as the warhorse was sweating.

It had been a strange meal, to say the least. Old Brother Benedictus had graced the provender and that was the last he said before he fell asleep with his head in his rose petals and gravy. The high table – himself, Bruce, the ladies, wee Jamie Douglas, the Inchmartins, Davey Siward and others -had been stiffly cautious.

All save Isabel, that is. The lesser lights had yapped among themselves, friendly enough save for those close to the salt, when the glowering and scowling began at who had been placed above and below it.

Conversation had been muted, shadowed by the distant cloud that was King Edward – even in France, Buchan thought moodily, Longshanks casts a long shadow. He had put Bruce right on a few points and been pleased about it, while giving nothing away to clumsy probings about his intentions regarding the rebelling Moray.

‘Exitus acta probat,’ he had answered thickly, choking on Isabel’s smiles and soft conversation with the Lady, talking right across him and ignoring him calculatedly.

‘I hope the result does validate the deeds,’ a cold-eyed Bruce had answered in French, ‘but that’s a wonderful wide and double-edged blade you wield there.’

Hal would have been surprised to find that he and Buchan shared the same thoughts, though his had been prompted by the sight of the Dog Boy, whose life had been wrenched apart and reformed at last night’s feast as casually as tossing a bone to a dog.

‘Your hounds are settled?’ Eleanor Douglas had called out to Hal, who had been placed – to his astonishment – at the top of the lesser trestle and within touching distance of the high table. He thought she was trying to unlatch the tension round her and went willing with it. Then he found she only added to it.

‘Yon lad is a soothe to them, mistress,’ he had replied, one ear bent to the grim, clipped exchanges between Buchan and Bruce.

‘It pleases me, then, to give you the boy,’ the Lady said, smiling. Hal saw the sudden, stricken look from Jamie, spoon halfway to his mouth, and realised that the Lady knew it, too.

‘Jamie will have me a wicked stepma from the stories,’ she went on, not looking at her stepson, ‘but he spends ower much time with that low-born chiel, so it is time they were parted and he learns the way of his station.’

Hal had felt the cleft of the stick and, with it, a spring of savage realisation – the hound-boy is a byblow of The Hardy, he thought to himself, and the wummin finds every chance to have revenge on wayward husband and her increasingly fretting stepson. Gutterbluid was one and now I am another – a dangerous game, mistress. He glanced at Jamie, seeing the stiff line of the boy, the cliff he made of his face.

‘I shall take careful care of the laddie,’ he had said, pointedly looking at Jamie and not her, ‘for if he quietens those imps of mine, he is worth his weight.’

He realised the worth of his gift only later and, staring at the scrawny lad, marvelled at the calm he brought to those great beasts; the Berner’s mean spirit came back to make Hal frown harder and he suddenly became aware that he was doing it while glaring at the Earl of Buchan.

Hastily, he formed a weak smile of apology, then turned away, but he realised later that Buchan had not been aware of him at all, had been concentrating, like a snake on a vole, on the arrival of his wife.

She appeared, a spot of blood on the vert of the day, smiling brightly and inclining her head graciously to her scowling husband, the huntsmen and hound boys. She sat astraddle, on a caparisoned palfrey – at least she is not riding my other warhorse this time, Buchan thought viciously – while the Lady of Douglas, demure and aware of her rank, rode sidesaddle and was led by Gutterbluid, who had her hawk on his wrist.

Isabel wore russet and gold and, incongruously to Hal, worn, travel-stained half-boots more suited to a man than a Countess, but the hooded cloak was bright as a Christmas berry. Hal realised all of it was borrowed from the Lady Douglas – save the boots, which were her own and all she had arrived with bar a green dress, an old travel cloak and a fine pair of slippers.

Jamie rode alongside her, a lute in one hand; he winked at Dog Boy, who managed a wan smile and the pair of them shared the sadness of this, their final moments together in all their lives to this point.

‘Wife,’ growled Buchan with a nod of grudged greeting and had back a cool smile.

‘La,’ she then said loudly, cutting through all the noise of dogs and horses and men. ‘Lord Robert – finches.’

Buchan brooded from under the lowered lintel of his brows at Bruce and his wife, playing the same silly game they had played all through last night at table. He felt the temper in him rising like a turd in a drain.

‘Easy. A chirmyng,’ Bruce replied. ‘Now one for you – herons.’

Hal saw the way Isabel pouted, her eyes sapphire fire and her hair all sheened with copper lights; he felt his mouth grow dry and stared. Buchan saw that too, and that irked him like a bad summer groin itch that only inflamed the more you scratched it.

‘A siege,’ she answered after only a short pause. ‘My throw – boys.’

Bruce frowned and squinted while the hunt whirled round them like leaves, not touching the pair of them, as if they sat in a maelstrom which did not ruffle a hair on either head. But Hal watched Buchan watching them and saw the hatred there, so that when Bruce gave in and Isabel clapped her hands with delight, Hal saw the Comyn lord almost lift off his saddle with rage.

‘Ha,’ she declared, triumphantly. ‘I have come out on top again.’

Then, as Bruce’s face flamed, Hal heard her add, ‘A blush of boys.’

‘If ye are done with your games,’ White Tam growled from the knotted root of his face, ‘we may commence the hunt.

‘My lord,’ he added, seeing Bruce’s scowl and managing to invest the term with more scathe than a scold’s bridle. Since White Tam was the Douglas head huntsman and more valued than even Gutterbluid the Falconer, Bruce could only smile and acknowledge the man with a polite inclination of his head.

‘Now we will begin,’ White Tam declared and flapped one hand; the cavalcade moved laboriously off, throwing clots up over the grass from the track that led into the forest alongside the Douglas Water. Dog Boy watched Gib being pulled into the wake of the hound cart by the deerhounds.

‘Peace, o my stricken lute, warbled Jamie shakily and plucked one or two notes, though the effect was spoiled by his having to break off and steer the horse.

‘Bloody queer battue this,’ Sim Craw growled, coming up to Hal’s elbow. Buchan and Bruce were armed and mailled, though they had left helms behind as a sop to false friendship and because what they wore was already a trial in the damp May warmth.

Buchan even rode his expensive warhorse, Sim pointed out, as if he expected trouble, while the shadow of Malise Bellejambe jounced at his back on a rouncey fitted with fat saddle-packs on either side.

‘Or would mak’ trouble,’ Hal answered and Sim stroked his grizzled chin and touched the stock of the great bow slung to one side of his rough-coated horse, watching the constantly shifting eyes of Bellejambe. Kirkpatrick, he noted, was nowhere to be seen and the entire fouled affair made him more savage at the mouth of the barrel-chested Griff, a foul-tempered garron, small, hairy and strong.

All his men rode the same mounts, small horses ideally suited for rough trod and long rides in the dark and the wet, with only a handful of oats and rainwater at the end of it. They could run for hours and sleep in snowdrifts, but would not stand up to a mass of men on horses the like of Buchan’s Bradacus – but Hal was Christ-damned if he would be caught in a fight on a mere gelded ambler.

Sim and two hands of riders, wearing as much protection as they could strap on, followed him and they were not sure whether they were here for hunt or herschip, since they were armed with long knives and Jeddart staffs.

Bruce’s smile was wry when he looked at them. It was hardly a hunting weapon, the Jeddart, an eight-foot shaft reinforced with iron for the last third, fitted with polearm spearpoint, a thin sliver of blade on one side and a hook like a shepherd’s crook on the other. Men skilled with it could lance from horseback, or dismount and form a small huddle of points, capable of hooking a rider out of the saddle, or slicing his expensive horse to ruin. Bruce, for all he thought they looked like mounted ruffians, saw the strength and use of them.

‘If you were April’s lad-ee and I were Lord of May, Jamie twittered as they scowled along the river road, the sun shining like a jest on their mockery.

They swung off the road, the carts lurching and the caged dogs whining eagerly. Dog Boy saw the forest, dark and musked, pearled with dawn rain. The trees, so darkly green they looked black, sprawled over hills alive with hidden life, tangled with bracken and scrub.

A place of red caps, dunters and powries, Sim Craw thought to himself and shivered at the idea of those Faeries. He liked the flat, long roll of Merse and March, bleak as an old whore’s heart; forests made him hunch his shoulders and draw in his neck.

The trees closed in and the road vanished behind them as the sun turned faint, staining the woods with dapple; the flies closed in, whirring and nipping, so that horses fretted and twitched.

‘What do they eat when we’re elsewhere?’ Bangtail whined, slapping his neck, but no-one wanted to open his mouth enough to answer, in case he closed it on cleg.

The Lady smiled at Hal and he remembered her turning to him in the Ward after Buchan and Bruce had gone off, arm in arm like returned brothers. He remembered it particularly for the astonishment in seeing her snub-nosed, chap-cheeked pig of a face softened by concern.

‘I know what this day has cost,’ she had murmured in gentle, courtly French and both the language and the sentiment had shocked him even more. Then she’d added, in gruff Scots, ‘Not me nor the boy here will be after forgetting, either. Ye’ll be sae cantie as a sou in glaur whenever ye come to Douglas after this.’

Sae cantie as a sou in glaur – happy as a pig in muck – and not the best offer Hal had ever had; for all her courtly French and De Lovaine breeding, the Lady of Douglas had the mouth of a shawled washerwoman when she chose. Hal thanked her all the same, while watching Buchan watching Bruce and the pair breaking off only to watch Isabel MacDuff.

The Lady of Douglas turned and spoke to White Tam, waving flies from her face. The old huntsman was like some gnarled tree, Buchan thought, but he knew the business well enough still. White Tam signalled and the whole cavalcade stopped; the hounds milled in their cages, yelping and whining.

A nod from the huntsman to Malk, and the houndsmen struck off the road and up into the trees with the carts, the dog boys leaning in to push over the scrub and rough; everyone followed and in a few steps it seemed to everyone as if the forest had moved, stepped closer and loomed over them, sucking up all noise until even Jamie gave up on his love dirges.

White Tam stood up slightly in the stirrups, a bulky, redfaced figure with a cockerel shock of dirty-snow hair which gave him his name. He had a beard which reminded Hal of an old goat and had one eye; the other, Hal had heard, had been lost fighting men from Galloway, in a struggle with a bear and in a tavern brawl. Any one, Hal thought, was possible.

The head hunstman rode like a half-empty bag of grain perched on a saddle. His back hurt and his limbs ached so much nowadays that even what sun there was in these times did nothing for him. It would have astonished everyone who thought they knew the old hunter to learn that he did not like this forest and the more he had discovered about it, the less he cared for it. He liked it least at this time of year and, at this moment, actively detested it, for the stags were coming into their best and the hunt would be long, hot and tiring.

The huntsman thought this whole farce the worst idea anyone had come up with, for a battue usually achieved little, spoiled the game for miles around for months and foundered good horses and dogs. He drew the ratty fur collar of his stained cloak tighter round him – he had another slung on the back of the horse, for experience had taught him that, on a hunt, you never knew where your bed might be – and prayed to the Virgin that he would not have to spend the dark of night in this place. Distantly, he heard the halloo and thrash of the beaters.

White Tam glanced sideways at the Sientclers, the Auld Templar of Roslin and the younger Sientcler from somewhere Tam had never heard of. His hounds, mind you, were a pretty pair and he wondered if they could hunt as well as they looked.

He watched the Lady Eleanor cooing to her hooded tiercel and exchanging pleasantries with Buchan and saw – because he knew her well now – that she was as sincere as poor gilt with the earl. That yin was an oaf, White Tam thought, who rides a quality mount to a hunt and would regret it when his muscled stallion turned into an expensive founder. An Andalusian cross with Frisian, he noted with expert eye, worth seven times the price of the mount he rode himself. Bliddy erse.

He considered the young Bruce, easy and laughing with Buchan’s wife. If she was mine, White Tam thought, I’d have gralloched the pair of them for makin’ the beast with two backs. It seemed that Buchan was blind or, White Tam thought to himself with years of observation behind it, behaving like most nobiles – biding his time, pretending nothing was happening to his dignity and honour, then striking from the dark and behind.

White Tam knew that men come to a battue armed as if for war was no unusual matter, for that style of hunt was designed for the very purpose of training young knights and squires for battle. Still, the old hunter had spoored out the air of the thing and could taste taint in it. The young Sientcler had confirmed it when he had come to Tam, enquiring about aspects of the hunt and frowning over them.

‘So we will lose each other, then,’ he had said almost wearily. ‘In the trees. Folk will scatter like chaff.’

‘Just so,’ White Tam had agreed, seeing the worry in the man and growing concerned himself; he did not want rival lords stalking one another in Douglas forests. So he spilled his fears to the Herdmanston lord, telling the man how there was always something went wrong on a hunt if people did not hark to the Rule of it all. Foundered horses, careless arrows – there had been injuries in the past and especially in a battue. Beside that, a bad shot, a wild spear throw, a stroke of ill luck, all frequently left an animal wounded and running and it was a matter of honour for the person who had inflicted the damage to pursue it, so that it did not suffer for longer than necessary. Alone, if necessary, and whether he was a magnate of the Kingdom or a wee Lothian lord.

‘Provided it is stag or boar,’ White Tam had added, wiping sweat drips from his nose. ‘Stag, as it is the noblest of God’s creations next to Man and boar for they are the most vicious of God’s creations next to Man and the worst when sair hurt.’

Anything else, he had told Hal pointedly, can be left to die.

Now he rose in the stirrups and held up a hand like a knotted red furze root, mottled as a trout’s belly. Then he turned to Malk, who was valet de limier for the day.

‘Roland,’ he said quietly and the dog was hauled out of one cartload. White Tam dismounted stiffly and, grunting, levered himself to kneel by the hound; they regarded each other sombrely and White Tam stroked the grey muzzle of it with a tenderness which surprised Hal.

‘Old man,’ he said. ‘Beau chien, go with God. Seek. Seek.’

He handed the leash to the grim-faced Malk and Roland darted off, tongue lolling, moving swiftly from point to point, bush to root, head down and snuffling impatiently as he hauled Malk after him. He paused, stiffened, loped a few feet, then determinedly pushed through the scrub and off into the trees at a fast, lumbering lope. The houndsmen and dog boys followed after, struggling with the carts.

Hal turned to Tod’s Wattie, who merely grinned and jerked his head: Gib came up on foot, the two deerhounds loping steadily ahead and hauling him along like a wagon. Hal returned the grin and knew that Tod’s Wattie would keep a close eye on the boy and, with a sudden sharpness deep in him, saw the dark dog boy slogging through the bracken.

Sim Craw saw it too and caught his breath – wee Jamie’s likeness, just as Hal had pointed out. Now there is a mystery . . .

‘Follow Sir Wullie and stay the gither,’ Hal said loudly, so that his men could hear. ‘Spread the word – bide together. If something happens, follow me or Sim. I do not want folk scattered, eechie-ochie. Do this badly and I will think shame to be seen with you.’

The men grunted and growled their assent and Sim urged his horse close to Hal.

‘What of the wummin, then?’ he asked, babe innocent. ‘Mayhap ye would rather chase the hurdies of the Coontess of Buchan?’

Hal shot him daggers and felt his face flame. God’s curses, had he been so obviously smit with Isabel MacDuff’s charms?

‘Let that flea stick to the wall,’ he warned and Sim held up a placatory hand.

‘I only ask what’s to be done,’ he said with a slight smile and the mock of it in his eyes. ‘Leave the Coontess to her husband – or Bruce, who is sookin’ in with her, as any can spy but the blind man wed on to her?’

Hal shot a look at the Countess, a flame in the dim light under the green-black trees, remembering how she had shone in the dark, too.

He had been fumbling his way to the jakes after the awkward feast, flitting as mouse-quiet as he could through the chill, grey, shadowed castle to the latrine hole. Halfway up the turn of a stair he had heard voices and stopped, knowing one was hers almost before the sound had cleared his ear. He moved on, so that he could peer over the top step along the darkened passage.

She was at the door of her room, barefoot and bundled in a great bearskin bedcover and clearly naked underneath it. Her hair was a russet ember in the shadows, tumbling in tendrils down white shoulders.

At the side of her door hung a shield, a little affair glowing unnaturally white in the grey dim, with a bar of blue across the top and the Douglas mullets bright on it. A gauntlet hung over it.

‘Young Jamie’s shield,’ she explained to the shadow, who clasped her close. ‘He hung it there with the metal glove, look there. He has sworn to be my knight and champion and hangs that there to prove it. If any refuse to admit that I am the most beauteous maid in all the world, they must strike the shield with the glove and be prepared to fight.’

The shadow shifted and laughed softly at this flummery while Isabel pouted hotly up into his mouth. For a moment, Hal’s breath had caught in his throat and he wished he was looking down, feeling that warmth on his lips.

‘Shall I strike it for you?’ she’d asked archly, and raised her long, white fingers, which spilled the fur from her shoulders and one impossible white breast, ruby-tipped like flame in the grey; Hal’s breath caught in his throat. ‘A tap, perhaps, just to see if he storms along the corridor.’

‘No need,’ the shadow declared, moving closer to the heat of her. ‘I have no argument with what he defends.’

She reached and he grunted. She smiled up into his eyes, moved a hand.

‘Nevertheless, Sir Knight,’ she said, slightly breathy. ‘It seems your lance is raised.’

‘Raised,’ the shadow agreed, guiding her into the doorway, so that the firelight fell on his face.

‘But not yet couched,’ Bruce added and the door closed on the pair of them.

A low, hackle-prickling bay snapped Hal from his revery and the caged hounds went wild.

‘Wind, wind!’ White Tam called out hoarsely – and unnecessarily, for everyone was heading towards the sound; Hal saw that Isabel had handed her hawk to the loping, hunched figure of the Falconer and was now spurring her horse away. Bruce, who had been admiring Eleanor’s hawk, now thrust it back at the Falconer and followed, the pair of them forging ahead. Hal heard her laugh as Bruce blew a long, rasping discordance on a horn.

The limiers, hauling against their leashes as the luckless dog boys panted after, forged stealthily off in the eerie silence bred into them, the scent Roland had spoored for them strong in their snouts.

Malk appeared with Roland, the hound panting and trembling with excitement. He struggled at the leash and sounded a long, rolling cry from his outstretched throat that was choked off as Malk hauled savagely on the leash.

‘Enough!’ growled White Tam and shot Philippe a harsh look, which carried censure and poison in equal measure. He saw the Berner’s mouth grow tight and then he was bellowing invective at the luckless Malk.

‘Hand him up,’ demanded White Tam and Malk, scowling, hauled the squirming Roland off the ground and up on to the front of the old huntsman’s saddle.

‘Swef, swef, my beauty. Good boy.’

White Tam suffered the frantic face licks and fawning of the hound, then tucked it under one arm and turned to Hal with a wry smile.

‘What a pity that when the nose is perfect, the legs have to go, eh?’

Roland was returned to Malk, who took him as if he were gold and carried him gently back to the cage. White Tam, frowning, looked down at the berner.

‘We will have Belle, Crocard, Sanspeur and Malfoisin,’ he declared. ‘Release the rapprocheurs.’

The hounds were drawn out and let slip, flying off like thrown darts, coursing left and right. Dog Boy saw Gib stagger a little under the slight strain of the two deerhounds, but a word from Tod’s Wattie made them turn their heads reproachfully and whine.

Dog Boy saw Falo start to run after the speeding dogs, leashes flapping in his sweating hands and remembered all the times he had been the one with that thankless, exhausting task. Now he had been handed to this new lord and it was no longer part of his life. He realised, with a sudden leap of joy, so hard it was almost rage, that he was done with Gutterbluid and his birds, too.

Behind Falo the peasant beaters struggled to keep up, locals rounded up for the purpose and, in the mid-summer famine between harvests, weak with hunger and finding the going hard on foot; the rapprocheurs’ sudden distant baying was wolfen.

Cursing, Hal saw the whole hunt fragment and stuck to the plan of following the Auld Templar, knowing Sir William would stick close to the Bruce and that Isabel would be tight-locked to the earl as well. If any Buchan treachery was visited, it would fall on that trio and Hal was determined to save the Auld Templar, if no-one else.

He forced through the nag of branches, looking right and left to make sure his men did the same. He urged Griff after the disappearing arse of Bruce’s mare, growling irritatedly as one of the Inchmartins loomed up, his stallion caught in the madness, plunging and fighting for the bit.

White Tam sounded a horn, but others blared, confusing just where the true line of the hunt lay; Hal heard the huntsman berate anyone who could hear about ‘tootling fools’ and suspected the culprit was Bruce.

A sweating horse crashed through some hazel scrub near Dog Boy and almost scattered Gib from the deerhounds, who sprang and growled. Alarmed and barely hanging on, Jamie Douglas had time to wave before the horse drove on through the trees.

A few chaotic, exhausting yards further on, Hal burst through the undergrowth to see Jamie sliding from the back of the sweat-streaked rouncey, which stood with flanks heaving. The boy examined it swiftly, then turned as Hal and the riders came up.

‘Lame,’ he declared mournfully, then stroked the animal’s muzzle and grinned a bright, sweaty grin.

‘Good while it lasted,’ he shouted and started to lead the horse slowly from the wood. Hal drove on; a thin branch whipped blood from his cheek and a series of short horn blasts brought his head round, for he knew that was the signal for the ‘vue’, that the quarry was in sight of the body of the hunt – and that he was heading in the wrong direction. Which, because he had been following the distant sight of red, made him angry.

‘Ach, ye shouffleing, hot-arsed, hollow-ee’ed, belled harlot,’ he bellowed, and men laughed.

‘The quine will not be happy at that,’ Sim Craw noted, but Hal’s scowl was black and withering, so he wisely fastened his lip and followed after. Two or three plunges later, Hal reined in and sent Bangtail Hob and Thom Bell after the Countess, to make sure she found her way safely back to join the hunt.

They forged on, ducking branches – something smacked hard on Hal’s forehead, wrenching his head back; stars whirled and he felt himself reel in the saddle. When he recovered himself, Sim Craw was grinning wildly at him.

‘Are ye done duntin’ trees?’ he demanded and looked critically at Hal. ‘No damage. Yer still as braw as the sun on shiny watter.’

Tod’s Wattie came up, shepherding a panting Gib and the running deerhounds, who were not even out of breath – but they were on long leashes now, held by Tod’s Wattie from the back of his horse, and starting to dance and whine with the smell of the blood, begging to be let loose. Dog Boy trotted up and Hal saw that, because he was not being hauled at breakneck pace by dogs, he was breathing even and clean; they grinned at one another.

Tod’s Wattie threw the leashes to Gib, who wrapped them determinedly in his fists, truculent as a boar pig. Horsemen milled in a sweating group; a few peasants stumbled to the boles of trees and sank down, exhaustion rising from them like haze. Horse slaver frothed on unseen breezes.

‘Bien aller,’ bellowed White Tam and raised the horn to his blue, fleshy lips, the haroo, haroo of it springing the whole crowd into frantic movement again. Berner Philippe, breathing ragged, gasped out a desperate plea for space for his hounds and White Tam rasped out another blast on his horn.

‘Hark to the line,’ he bellowed. ‘Oyez! Ware hounds. Ware hounds.’

The stag burst from the undergrowth and, a moment later, a tangled trail of baying hounds followed, skidding in confusion as the beast changed direction and bounded away.

It stank and steamed, rippling with muscle and sheened like a copper statuette, the great horned crown of it soaring away into the trees as it sprang, scattering hounds and leaping majestically, leaving the dogs floundering in its wake. The powerful alaunts had been released too soon, White Tam saw, and had already been left behind, for they had no stamina, only massive strength.

‘Il est hault, he roared, purple-faced. Tl est hault, il est hault, il est hault.’

‘Tallyho to you, too,’ muttered Hal and then tipped a nod to Tod’s Wattie, who grinned and nudged Gib.

White Tam cursed and banged the horn furiously on the cantle, for he could see the stag dashing away – then two grey streaks shot swiftly past on either side of him, silent as graveshrouds. They overtook the running stag, barging in on one side and forcing it to turn at bay. The deerhounds . . . White Tam almost cried out with the delight of it.

Dog Boy gawped. He had never seen such speed, nor such brave savagery. Mykel dashed for the rear; the stag spun. Veldi darted in; the stag spun – the hound seized it by the nose and the stag shook it off, spraying furious blood. But Mykel had a hock in his jaws and the back end of the beast sank as the rest of the pack came up and piled on it.

Even then the stag was not done. It bellowed, fearful and desperate, swung the massive antlered head and a dog yelped and rolled out like a black and tan ball, so that Dog Boy felt a kick in him, sure that it had been Sanspeur.

Tod’s Wattie shouted once, twice, three times but the grey deerhounds clung on and the stag hurled itself off into the forest, staggering, stumbling, dragging the deerhounds and the rest of the pack in a whirling ball. Hal bellowed with annoyance when he saw Mykel ripped free from the hindquarters of the beast, the leash that should have been removed before he’d been released snagged on something in the undergrowth.

Choking, the hound floundered, trying to get back into the fray, gasping for breath and doing itself no good by its own frantic, lunging efforts. Tod’s Wattie lashed out at Gib, who knew he had erred but was too afraid of the hound to go forward and release it – but a small shape barrelled past him, right to where the gagging deerhound whirled and snarled.

Dog Boy ignored the sight of the fangs, sprang out his eating knife and sawed the cord free from the dog’s neck, the white, sharp teeth rasping, snapping close to his face and wrists. Released, Mykel sprang forward at once with a hoarse, high howl and, the other hand caught in its hackled ruff, Dog Boy went with it, grimly hanging on – Hal saw the blood on the dog’s muzzle and marvelled at the boy’s bravery and sharp eyes.

Mykel checked then, rounded on Dog Boy and he saw the maw of it, the reeking heat of the muzzle. Then the deerhound whined with concern and licked him, so that the stag blood smeared over Dog Boy’s face. When Tod’s Wattie came up with Hal and the others, he turned and grinned at Hal, nodding appreciatively because the boy, heedless of teeth and covered in blood and slaver, was examining Mykel’s mouth to make sure all the blood belonged to the stag.

Tod’s Wattie tied on a new leash, scowling at Gib. Hal leaned down towards Dog Boy and Sim Craw saw the concern.

‘Yer a bit bloody, boy,’ Hal said awkwardly and Dog Boy looked at him while the huge beast of a deerhound panted and fawned on him. He smiled beatifically. There was something huge and ecstatic in his chest and the raw power of it locked with this new lord and made them, it seemed, one.

‘So is yourself, maister.’

Sim Craw’s laugh was a horn bellow of its own and Hal, ruefully touching his cheek and forehead, looked at the blood on his gloved fingers, acknowledged the boy with a wave and went on after the hunt.

The pack was milling and snarling and dashing backwards and forwards, save for the powerful alaunts, who had caught up at last and charged in. One was locked to the stag’s throat, another to one thin, proud leg and a third to the animal’s groin, jerking it this way and that. The stag’s dulling eyes were anguished and hopeless and, too weary now to fight, it suffered the agony in a silence broken only by the bellow rasp of its breathing, blowing a thin mist of blood from flaring nostrils.

White Tam, reeling precariously in his saddle, barked out orders and the hound and huntsmen moved in with whips and blades to leash the dogs and give the beast the grace of death.

‘A fine stag,’ he said to Hal, beaming. ‘Though it is early in the year and there will be finer come July. What will you take for yon dugs?’

Hal merely looked at him, raised an eyebrow and smiled. White Tam slapped one hand on his knee and belched out a laugh.

‘Just so, just so – I would not part with them neither.’

Dog Boy heard this as if from a distance, for his world had folded to the anguish on Berner Philippe’s face and the mournful dark eye of Sanspeur. The rache whined and tried to lick Dog Boy’s hand and, for a moment, they knelt shoulder to shoulder, the Berner and Dog Boy.

‘Swef, swef, ma belle, Philippe said and saw that the leg was smashed beyond repair. There was a moment when he became aware of the boy and looked at him, the thought of what he had to do next a harsh misery in his eyes, and Dog Boy saw it. The Berner felt something sharp and sweet, a pang which drove the breath from him when he looked into the eyes of the dog he would have to kill. He loved this dog. The knife flashed like a dragonfly in sunlight.

‘Fetch a mattock,’ he grunted and, when nothing happened, jerked his head to the boy. Then he saw the look on Dog Boy’s face as he stared at the filming eyes of the dying dog and the harsh words clogged in his throat. He found, suddenly, that he was ashamed of how hard he grown in the years between now and when he had been Dog Boy’s age.

‘If you please,’ he added, yet still could not keep the slightest of sneers from it. Dog Boy blinked, nodded and fetched a mattock and a spade, while the dogs were hauled away and the stag butchered. Between them, they dug a hole under a tree, where the ground was mossy and still springy and put the dog in it, then covered it with mould, black leaves and earth.

Sanspeur, Philippe thought. Without fear. She had been without fear, too and that had been her undoing. It was better to be afraid, he thought to himself, and stay alive. The boy, Dog Boy, knew this – Philippe turned and found himself alone, saw the boy moving from him, back to the big deerhounds and the hard, armed men he now belonged to. He did not look afraid at all.

There was a flurry off to one side, a flash of berry red, and Isabel appeared, cheeks flushed, hood back and her fox-pelt hair wisping from under the elaborate green and gold padded headpiece, her face wrinkling distaste at the blood and guts and flies. Behind her came Bruce, riding easily, and after them Bangtail Hob and Thom Bell, all black scowls and slick with a sweat that was mead for midges.

‘There’s your wummin,’ Sim said close to Hal’s elbow. ‘Safe enow. What was it ye called her – a hot-arsed . . . what?’

Then he chuckled and urged ahead before Hal could spit out for him to mind his business.

‘Martens,’ Isabel called out gaily and Bruce, laughing, came up with it almost at once – a richesse. Hal saw Buchan scowl and, fleetingly, wondered where Kirkpatrick was.

A tan, white-scutted shape burst out of the undergrowth, almost under the hooves of Bradacus, which made the great warhorse rear. Buchan, roaring and red-faced, sawed at the reins as he and the horse spun in a dancing half-circle, then lashed out with both rear hooves, catching Bruce’s horse a glancing blow.

Bruce’s rouncey, panicked beyond measure, squealed and bolted, the rider reeling with the surprise of it, while the dogs went mad and even the big deerhounds lurched forward, to be brought short by Dog Boy and Tod’s Wattie’s tongue.

Isabel threw back her head and laughed until she was almost helpless.

‘Hares,’ she called out to Bruce’s wild, tilting back and Hal, despite himself, felt the flicker of his groin and shifted in the saddle. Then he realised the Berner was bellowing and half-turned to see the biggest brute of the alaunts, unused in the hunt and fighting fresh, rip its chains out of its handler’s fists and speed off after Bruce, snarling.

There was a frozen moment when Hal looked at Sim and both glanced to where Malise, off his horse, stared after the fleeing hound with a look halfway between feral snarl and triumph. In a glance so fast Hal nearly missed it, he then turned and looked at the alaunt handler, who looked back at him.

The chill of it soured deep into Hal’s belly. The hound had been deliberately released – and a trained warhorse frightened by a leaping hare?

‘Sim . . .’ he said, even as he kicked Griff, but the man had seen it for himself and spurred after Hal, bellowing for Tod’s Wattie and Bangtail Hob. Buchan, bringing Bradacus miraculously back under control, watched them crash through the undergrowth in pursuit of Bruce and tried not to smile.

White Tam, hunched on the mare, ploughed on relentlessly while the hunt swirled and whirled around him, knowing the truth of matters – that he was too old and slow these days, so that he reached the hunt when it was all over bar the cutting up. White Tam knew the ritual of cutting up well now, talked more and more in a language gravy-rich with os and suet, argos and croteys, grease and fiants.

He was aware only of the vanishing of Bruce and the others as an annoyance by well-bred oafs who chased hares.

‘Go after the Earl of Carrick,’ he ordered those nearest. ‘Mak’ siccar he does not tumble on his high-born arse.’

Bruce, half-clinging on for dear life, finally got control of the rouncey and became aware, suddenly and with a catch of fear in his throat, that he was alone. He turned this way and that, hearing shouts but confused as to direction then, for fear his anxiety would cause the trembling horse to bolt again, he got off the animal and stroked it quiet, neck and muzzle.

The leveret was long gone and he shook his head at the shame of having let his mount bolt, even if it had been sorely provoked by a kicking destrier. Hares, he thought with a savage wryness. A husk of hares – he would take delight in telling her.

He looked round at the oak and hornbeam, the sun glaring cross-grained through branches, thinly prowling over his face like delicate, warm cat paws. The bracken was crushed here, there was a smell of broken grass and turned earth and the iron tang of blood, which made Bruce uneasy. The mystery of how a hare, which was not a forest animal at all, had been there at all nagged him a little and the worry of plots surfaced like sick.

Then he realised this was where the stag had been brought to bay by the deerhounds and relaxed a little, which in turn brought the rouncey to an even breathing. Even so, there was a musk that puzzled him, the more so because it came from the rouncey’s sweat-foamed sides and the saddle; he had been smelling it all day.

The alaunt came out of the undergrowth like an uncurling black snake, a matted crow of snarls that skidded, paused and padded, slow and purposeful, the shoulders hunched and working, the slaver dripping from open jaws.

Bruce narrowed his eyes, then felt the first stirrings of fear – it was stalking him. Then, with a deep panic he had to grip himself to fight, he realised what the musk smell was and that hare scent, blood and glands, had been deliberately smeared on saddle and horse flank. A deal of hare scent, too, now transferred to himself.

There was a pause and Bruce fought to free the dagger at his belt, cursing, seeing the inevitable in the gathering tremble of the beast’s haunches. Somewhere, he heard shouts and the blare of a hunting horn – too far, he thought wildly. Too far . . .

The black shape launched forward, low and fast, boring in to disembowel this strange, large, two-legged prey that smelled right and looked wrong. The rouncey squealed and reared and danced away, reins caught in the bracken, and the alaunt, confused by scent from two victims, paused, chose the smaller one and, snarling, tore forward.

There was a streak through the grass, a fast-moving brindle arrow, rough-haired and uncombed. It struck the flank of the alaunt in mid-leap and Bruce, one forearm up to protect his throat, reeling back and already feeling the weight and the teeth of the affair, saw an explosion of snarls and a ball of fur and fang rolling over and over until it separated, paused and then alaunt and Mykel surged back at each other like butting rams.

Their bodies whirled and curled, opened and shut. Fangs snapped and throats snarled; one of them squealed and bloody slaver flew. Bruce, shocked, could only watch while the rouncey danced and screamed on the end of its tether – then a second grey shape barrelled in and the ball of fighting hounds rolled and snarled and fought a little longer until the alaunt, outmatched even by one, broke from the pair of deerhounds and sped away.

Hal and Sim came up, trailing Tod’s Wattie, the Dog Boy with a fistful of leashes and a cursing Bangtail Hob in his wake. They all arrived in time to see the alaunt, close hauled by the ghost-grey shapes, suddenly fall over its own front feet, roll over and over and then sprawl, loose and still. The deer-hounds overran it and had to skid and backtrack, only to find their prey so dead they could only paw it, snarling and whining in a thwarted ecstasy of lost bloodlust, puzzled at the leather-fletched sapling which had sprouted from the hunting dog’s neck.

From out of a nearby copse strolled Kirkpatrick, latchbow casually over one shoulder.

A fine shot, Sim noted with a detached part of his brain. What was he doin’, sleekit in the trees with a latchbow? He could not find the voice for it – did not need to – as the Dog Boy ran to secure the hounds and Hal and Bruce exchanged looks.

‘If you are allowed to search the saddle-bags of yon Malise,’ Kirkpatrick said, in a voice as easy as if they were discussing horses at table, ‘you will surely find it full of hare shite. Terrifying for a wee leveret, to be shut up in the bouncing dark until needed. You will find also that the alaunt handler has been spirited away, though I will wager he’ll not long enjoy the payment he had for releasing yon monster on cue. You will not find him at all, I suspect.’

No-one spoke, until Bruce turned to the snorting, panting, wild-eyed rouncey and gathered up the reins, the trembling fear in him turning to anger at what had been revealed, at the cunning planning in it and, if truth be told, his own secret attempt against Buchan.

In his mind’s eye, for a fleeting, bowel-wrenching flicker, he saw the dog’s great jaws and the long, leaping shape of it – he wrenched to free the reins from the tangle, felt them give then catch again; irritated, he hauled with all his strength.

Death ripped up out of the earth and leered at him.

Douglas Castle The next day

The hunt ended like a trail of damp smoke, filtering back in near-silence to the castle. Bruce, too bright and brittle to be true, flirted even more outrageously with the Countess, though her exchanges seemed strained and she was too aware of Buchan’s glowering.

No-one could stop looking at the cart which held the body – though Hal had seen Kirkpatrick, riding silent and cat-hunched with a face as sightless and bland as a stone saint. Here was a man who had just seen his liege lord under attack and should be head-swinging alert – yet he stared ahead and saw nothing.

He should, Hal said to Sim later, be like a mouse sniffing moonlight for more owls.

‘You would so think,’ Sim agreed – but he was distracted, had come in from the dark night of the Ward to report that he’d seen the Countess, huckled like a bad apprentice across to the Earl of Buchan’s tent by Malise and two men in leather jacks and foul grins. The noises that came from it then set everyone’s teeth on edge.

In the comfort of the kitchen, old limbs wrapped to ease the ache, White Tam nodded approval; the Earl of Buchan had finally seen sense ower his wayward wummin.

‘A woman, a dog and an old oak tree,’ he intoned. ‘The more you beat them, the better they be.’

‘Why an oak tree, Master?’ demanded one of the scullions and Tam told him – sometimes such a tree stopped producing valuable acorns for the pigs, so some stout men, including the Smith with his forge hammer, would walk round it, hitting it hard. It started the sap up again and saved the tree.

Dog Boy, fetching scraps for the hounds, listened to the sick sounds and thought of the Countess being hit by a forge hammer. He did not think her sap would rise.

There was worse to come, at least for Hal, as the morning crept closer – the Auld Templar shifted out of the shadows like a wraith and, with a pause for a single deep breath, like a man ducking underwater, said:

‘I need to call on your aid.’

Hal felt the chill of it right there.

‘I am, as ever, fealtied to Roslin,’ he replied carefully and saw the old man’s head jerk at that. Aha – so I am right, he thought. He summons me as a liege lord.

‘Before my son came of age,’ the Auld Templar said slowly, ‘I was lord of Roslin. I taught the young Bruce how to fight.’

Hal said nothing, though that fact explained much about the Templar’s presence with the Earl of Carrick.

‘When my son was able, I handed him Roslin and gave my soul and arm to God,’ the Templar went on. ‘I have never regretted it – until now.’

He stared at Hal, pouch eyes flickered with torchlight.

‘I cannot be seen to fight for one side or the other,’ he went on. ‘But Roslin must jump.’

‘To the Bruce,’ Hal said bleakly and had back a nod.

‘The Sientcler Way,’ Hal added, hearing the desperation in his own voice. The Sientcler Way was always to have a branch of the family on either side of a conflict. That way, triumph or loss, the Sientclers always survived.

The Auld Templar shook his head.

‘This conflict is too large and the Sientclers are too thinned. This time, we must jump one way and pray to God.’

‘You wish me to serve the Bruce, in your stead,’ Hal declared flatly; the Templar nodded.

It was hardly a surprise. Roslin owed fealty to the Earl of March, Patrick of Dunbar – and so, therefore, did Herdmanston – but Earl Patrick was lockstepped with Longshanks and, with a son and grandson held by the English, the Auld Templar was inclined to those who opposed them.

‘My father,’ Hal began and the Auld Templar broke in.

‘Is at home,’ he said. ‘He sent word that the Earl of March refuses to help return my boys to me. Just punishment for rebellion, he says. The Earl of Carrick has promised help with ransoms.’

Well, there it was – sold for the price for two men from Roslin. Hal felt his mouth dry up. Herdmanston was put at risk and his father with it – yet he knew the Auld Templar had weighed that in the pan and still found the price acceptable.

‘Then we are bound – where?’ Hal asked, sealing it as surely as fisting a ring into wax. For a moment the Auld Templar looked broken and Hal realised the weight crushing those bony shoulders, wanted to offer some reassurance. The lie choked him – and the Auld Templar’s next words would have made mockery of it in any case.

‘Irvine,’ he said and forced a grin to split his snowy beard. ‘The Bruce is off to treat with rebels.’

Hal stared at the space where the Auld Templar had been long after the dark had swallowed the man – until Sim found him and, frowning, asked him why he was boring holes in the dark. Hal told him and Sim blew out his cheeks.

‘Rebels are we then?’ he declared and shrugged. ‘Bigod -that puts us at odds with the chiel who has also just asked for our aid. I would not mention it.’

The Earl of Buchan was in the undercroft, coldest hole in Douglas and the resting place of the mysterious body. In the soft, filtered light of early morning, you could see why the body had drained the blood from Bruce’s face when he’d had it torn from the mulch almost into his face.

Kirkpatrick, too, had looked stricken – but, then, no-one was chirruping songs to May at the sight of the half-eaten, rotted affair, undeniably human and undeniably a man of quality from the remains of his clothing and the rings still on his half-skeletal fingers.

Not robbed then, for a thief would have had his rings and searched under armpits and bollocks, the place sensible men kept most of their heavy coin. The dead man had a purse with some little coin in it still snugged up in a scrip with what looked to be spare braies, but no weapon. No-one, at first, wanted to go near the corpse save Kirkpatrick and, when he left it, he closeted himself with Bruce.

Grimacing with distaste, Buchan had assumed the mantle of responsibility for it and now beckoned Hal and Sim Craw to where the reeking remains lay on the slabbed floor. He spoke in slow, perfect English so that Sim Craw, whose French was poor, could understand.

‘White Tam has had a look but the most he can tell is that it is a year dead at least,’ Buchan had declared. ‘He says he is just a huntsman, but that yourself and Sim Craw are the very men for looking over bodies killed by violence. I am inclined to agree.’

Hal did not care for this unwelcomed skill handed to him by White Tam, nor did he want to be closeted with Buchan following the events of the hunt and the Auld Templar, but it appeared the earl was not put out at having his plans foiled by a wee lord from Lothian and a pair of splendid dogs. Hal had to admire the blithe dismissal of what would have been red murder if he had been allowed to succeed – but he did not want to be cheek by jowl with this man, who held a writ from the distant thunder that was King Edward to hunt out rebels in the north.

He thought to refuse the earl, using the excuse of not wanting to go near the festering remains, but he had seen Kirkpatrick’s face in the instant the effigy had been torn up by Bruce’s reins and in the long ride back. Now such a refusal was a blatant lie his curiosity undermined. Swallowing, driven by the desire of knowing, Hal had looked at Sim Craw, who had shrugged his padded shoulders in return.

‘A wise man wavers, a fool is fixed,’ he growled meaningfully, then sighed when he saw it made no difference, following Hal to the side of the thing, trying to breathe through his mouth to keep the stink out of his nose.

‘Christ be praised,’ Buchan said, putting a hand over his lower face.

‘For ever and ever,’ the other two intoned.

Then Sim poked his gauntleted hand in the ruin of it, peeled back something which could have been cloth or rotted flesh and pointed to a small mark on a patch of mottled blue-black.

‘Stabbed,’ he declared. ‘Upward. Thin-bladed dagger – look at the edges here. A wee fluted affair by the look. Straight to his heart and killit him dead.’

Hal and Sim looked at each other. It was an expert stroke from a particular weapon and only a man who killed with it regularly would keep a dagger like that about him. Wildly, Hal almost asked Buchan if he and Bruce had hunted in these woods before and had lost a henchman. He thought of the two deerhounds, slathered with balm and praises, and the dead alaunt, bitterly buried by the Berner.

‘So,’ Sim declared. ‘A particular slaying – what make ye of this, Hal? When the slayer was throwin’ him down, d’ye think?’

It was a cloth scrap, a few threads and patch no bigger than a fingernail, caught in the buckle of the dead man’s scrip baldric. It could have been from the man’s own cloak, or another part of his clothing for all the cloth was rotted and colour-drained, but Hal did not think so and said as much.

Sim thought and stroked the grizzle of his chin, disturbed a louse and chased it until he caught it in two fingers and flicked it casually away. He turned to Hal and Buchan, who was wishing he could leave the festering place but was determined, on his honour and duty as an earl of the realm, to stay as long as the others.

‘This is the way of it, I am thinking,’ Sim said. ‘A man yon poor soul knows comes to him, so getting near enough to strike. They are in the dark, ken, and neb to neb, which is secretive to me. Then the chiel with the dagger strikes . . .’

He mimicked the blow, then grabbed Hal by the front of his clothes and heaved him, as if throwing him over on to the ground. He was strong and Hal was taken by surprise, stumbled and was held up by Sim, who smiled triumphantly and nodded down to where the pair of them were locked, buckle to buckle, Sim’s leg between Hal’s two.

Hal staggered upright as Sim let go, then explained what had just happened to the bewildered Buchan, who had understood one in six words of Sim’s explanation in Lowland Lothian. Like wood popping in a fire, the earl thought.

‘Aye,’ Hal said at the end of it, ‘that would do it, right enough – well worked, Sim Craw.’

‘Which does not explain,’ Buchan said, ‘who this man is. He is no peasant with these clothes – Kirkpatrick said as much when he was here.’

‘Did he so?’ mused Sim, then looked closely at the dead man, half yellow bone, half black strips of rot, some cloth, some flesh. An insect scuttled from a sleeve, down over the knucklebones, slithering under a mottled leather pouch. Sim worried the pouch loose, trying to ignore the crack of the small bones and the waft of new rot that came with him disturbing the body. He opened it, shook the contents on to the palm of his hand and they peered. Silver coins, a lump of metal with horsehair string attached, a medallion stamped with the Virgin and Child.

‘No robbery, then,’ Hal declared, then frowned and indicated the brown, skeletal hand.

‘Yet a finger has been cut.’

‘To get at a tight-fitting ring,’ Sim said, with the air of man who was no stranger to it, and Buchan lifted an eyebrow at the revelation.

‘Yet no other rings are taken,’ he pointed out, and Hal sighed.

‘A wee cat’s cradle of clues, right enow,’ he declared, looking at the contents of the purse. The medallion was a common enough token, a pardoner’s stock in trade to ward off evil, but the teardrop metal lump and string was a puzzler.

‘Fishing?’ Buchan suggested hesitantly and Hal frowned; he did not know what it was but fishing seemed unlikely. Besides, it was knotted in regular progression and unravelled to at least the height of a man.

‘It is a plumb line,’ Sim said. ‘A mason uses it to mark where he wants stone cut – see, you chalk the string, hold the free end and let the weight dangle, then pluck it like a harp string to leave a chalk line on the stone.’

‘The knots?’

‘Measurement,’ Sim answered.

‘A mason?’ Buchan repeated, having picked that part out ‘Is this certes?’

Hal looked at Sim, eyebrows raised quizzically.

‘Am I certes? Is a wee dug bound by a blood puddin’?’ Sim answered indignantly. ‘I am Leadhoose born, up by the wee priory of St Machutus what the Tironensians live in. My father was lifted to work with the monks, who were God’s gift for buildin’.’

‘Tironensians. I know that order,’ Buchan said, recognising that word in the welter of thick-accented braid Scots. ‘They are strict Benedictines, finding glory in manual labour. They are skilled – did they not do the work at the abbeys in Selkirk, Arbroath and Kelso? You think this mason is a Benedictine from that place?’

‘Mayhap, though he is not clothed like any monk I ken,’ Sim declared. ‘But my da was lifted from the cartin’ to work with them at the quarrystanes and then came to Herdmanston to dig a well. Until I was of age to go off with young Hal here, I worked at the digging and the drystane. I ken a plumb line – the knots are measured in Roman feet.’

He closed his eyes, the better to remember.

‘Saint Augustine says six is the perfect number because the sum and product of its factors – one, two, and three – are the same. Thus a thirty-six-foot square is the divine perfection, much favoured by masons who build for the church. Christ be praised.’

He opened his eyes into the astounded stares of Hal and the Earl of Buchan and then blinked with embarrassment as they stumbled over the rote response, almost dumbed by the revelation of a Sim with numbers.

‘Aye, weel – tallyin’ is not my strength, though I ken the cost of a night’s drink. But my da dinned plumb lines into me, for ye can dig neither well nor build as much as a cruck hoose without it.’

‘You think it was a mason from St Machutus?’ the earl demanded, narrow eyed and cock-headed with trying to understand. Sim shook his head.

‘It’s a mason, certes. And a master, if his fine cloots are any guide.’

‘Aye,’ Hal said wryly. ‘Since English Edward knocked about some fine fortresses last year, I daresay there are a wheen of master masons at work in Scotland.’

‘Not our problem,’ Buchan said suddenly, eager to be gone from the place. He plucked weight, string, medallion and coins from Sim’s palm and tossed them carelessly back into the mess on the table.

‘Evidence,’ he declared. ‘We will wrap this up and deliver it to the English Justiciar at Scone. Let Ormsby deal with it. I have a rebellion to put down.’

Irvine

Feast of St Venantius of Camerino, May, 1297

The sconces made the shadows lurch and leer, transported a bishop to a beast. Not that Wishart looked much like the foremost prelate in Scotland, sitting like a great bear in his undershift, the grey hair curling up under the stained neck of it above which was a face like a mastiff hit with a spade.

‘More of a hunt than you had bargained, eh, Rob?’ he growled and Bruce managed a wan smile. ‘Then to find a corpse . . . Do we ken who it is, then?’

The last was accompanied by a sharp look, but Bruce refused to meet it and shook his head dismissively.

‘Buchan carted the remains off to Ormsby at Scone. I said to go to Sheriff Heselrig at Lanark, but he insisted on going to the Justiciar.’

He broke off and shot looks at the men crowded into the main hall of the Bourtreehill manor.

‘Did he know? Did Buchan know that Heselrig was already dead and Lanark torched?’ he hissed and Wishart flapped an impatient hand, as if waving away an annoying fly.

‘Tish, tosh,’ he said in his meaty voice. ‘He did not. No-one knew until it was done.’

‘Now all the realm knows,’ growled a voice, and The Hardy stuck his slab of a face into the light, scowling at Bruce; Hal saw that he was a coarser, meatier version of Jamie. ‘While you were taking over my home, Wallace here was ridding the country of an evil.’

‘You and he were, if the truth be told, torching our lands around Turnberry,’ Bruce countered in French, swift and vicious as a stooping hawk. ‘That’s why my father was charged to bring you to heel by sending me to Douglas – as well, my lord, that I had less belly for the work than you, else your wife and bairns would not be tucked up safe a short walk away.’

‘You were seen as English,’ The Hardy muttered, though he shifted uncomfortably as he spoke; they both knew that The Douglas had simply been taking the opportunity to plunder the Bruce lands.

‘That was not the reason Buchan tried to have me killed,’ Bruce spat back, and The Hardy shrugged.

‘More to do with his wife, I should think,’ he said meaningfully, and Bruce flushed at that. Hal had seen the Countess early the next day, mounted on a sensible sidesaddled palfrey and led by Malise out of Douglas, with four big men and the Earl of Buchan’s warhorse in tow. Headed back to Balmullo, he had heard from Agnes, who had been her tirewoman while she stayed in Douglas. Ill-used to the point of bruises, she had added.

‘He tried to have me killed,’ Bruce persisted and Hal bit his lip on why Kirkpatrick had been loose in the woods with a crossbow, but the sick meaning of it all rose in him, cloyed with despair; the most powerful lords in Scotland savaged each other with plot and counterplot, while the Kingdom slid into chaos.

‘Aye, indeed,’ Wishart said, as if he had read Hal’s mind, ‘it’s as well, then, that Wallace here put a stop to the Douglas raids on the Bruce, in favour of discomfort to the English in Lanark. A proper blow. A true rebellion.’

Douglas scowled at the implication, but the man in question shifted slightly, the light falling on his beard making it flare with sharp red flame. The side of his face was hacked out by the shadows and, even sitting, the power of the man was clear to Hal and everyone else. His eyes were hooded and dark, the nose a blade.

‘Heselrig was a turd,’ Wallace growled. ‘A wee bachle of a mannie, better dead and his English fort burned. He was set to assize me and mine for a trifle and would have been savage at it.’

‘Indeed, indeed,’ Wishart said, as if soothing a truculent bairn. ‘Now I will speak privily with the Earl of Carrick, who has come, it seems, to add his support to the community of the realm.’

‘Has he just,’ answered Wallace flatly and stood up, so that Hal saw the size of him – enough of a tower for him to take a step back. Wallace was clearly used to this and merely grinned, while The Hardy followed him as he ducked through the door, arguing about where to strike next.

Wishart looked expectantly at Kirkpatrick and Hal, but Bruce started to pace and glower at him.

‘They are mine,’ he said, as if that explained everything. Hal bit his lip on the matter, though he knew he should have walked away from the mess of it, before the wrapping chains of fealty to the Roslin Sientclers shackled him to a lost cause.

He glanced over at Kirkpatrick and saw the hooded stare he had back. Noble-born, Hal thought, and carries a sword, though he probably does not use it well. Not knighted, with no lands of his own – yet cunning and smart. An intelligencer for The Bruce, then, a wee ferret of secrets – and a man Bruce could send to red murder a rival.

‘So – you and Buchan, plootering about in the woods like bairns, tryin’ to red murder yin another?’ Wishart scathed. ‘Hardly politic. Scarcely gentilhommes of the community of the realm, let alone belted earls. Then there is this ither matter – ye never saw the body, then?’

Bruce rounded on him like a savaging dog, popping the French out like a badly sparking fire.

‘Body? Never mind that – what in God’s name are you up to now, Wishart? The man’s a bloody-handed outlaw. Barely noble – community of the realm, my arse.’

Wishart sipped from a blue-glass goblet, a strangely delicate gesture from such a sausage-fingered man, Hal thought. The bishop stared up into Bruce’s thrusting lip and sighed.

‘Wallace,’ he said heavily. ‘The man’s a noble, but barely as you say. The man’s an outlaw, no argument there.’

‘And this is your new choice for Scotland’s king, is it?’ Bruce demanded sneeringly. ‘It is certainly an answer to the thorny problem of Bruce or Balliol, but not one, I think, that your “community of the realm” will welcome. A lesser son, a family barely raised above the level? Christ’s Bones, was he not bound to be a canting priest, the last refuge of poor nobiles?

‘Aye, weel – some become bishops,’ Wishart answered mildly, dabbing his lips with a napkin, though the stains down the front of his serk bore witness to previous carelessness and Bruce had the grace to flush and begin to protest about present company. Wishart waved him silent.

‘Wallace is no priest,’ he answered. ‘No red spurs nor dubbing neither, but his father owns a rickle of land and his mother is a Crawfurd, dochter of a Sheriff of Ayr – so he is no chiel with hurdies flappin’ out the back of his breeks. Besides, he is a bonnie fighter – as bonnie as any I have ever seen. As a solution to the thorny problem of Bruce or Balliol it takes preference over murder plots on a chasse, my lord.’

‘Is that all it takes, then?’ Bruce demanded thickly. ‘You would throw over the Bruce claim for a “bonnie fighter”?’

‘The Bruce claim is safe enough,’ Wishart said, suddenly steely. ‘Wallace is no candidate for a throne – besides, we have a king. John Balliol is king and Wallace is fighting in his name.’

‘Balliol abdicated,’ Bruce roared and Kirkpatrick laid a hand on his arm, which the earl shook off angrily, though he lowered his voice to a hoarse hiss, spraying Wishart’s face.

‘He abdicated. Christ and All His Saints – Edward stripped the regalia off him, so that he is Toom Tabard, Empty Cote, from now until Hell freezes over. There is no king in Scotland.’

‘That,’ replied Wishart, slowly wiping Bruce off his face and staring steadily back at the pop-eyed earl, ‘is never what we admit. Ever. The kingdom must have a king, clear and indivisible from the English, and Balliol is the name we fight in. That name and the Wallace one gains us fighting men – enough, so far, to slay the sheriff of Lanark and burn his place round his ears. Now the south is in rebellion as well as the north and east.’

‘Foolish,’ Bruce ranted, pacing and waving. ‘They are outlaws, cut-throats and raiders, not trained fighting men -they won’t stand in the field and certainly not led by the likes of Wallace. Your desperation for a clear and indivisible king blinds you.’

He leaned forward and his voice grew softer, more menacing while the shadows did things to his eyes that Hal did not like.

‘Only the nobiles can lead men to fight Edward,’ he declared. ‘Not small folk like Wallace. In the end, the gentilhommes – your precious “community of the realm” – is what will keep your Church free of interference from Edward, which is really what you finaigle for. Answerable only to the Pope, is that not it, Bishop?’

‘Sir Andrew Moray is noble,’ Wishart pointed out, bland as a nun’s smile, and that made Bruce pause. Aha, Hal thought, the bold Bruce does not like the idea of Moray. Moray and Wallace as Guardians of the Realm would go a long way to appeasing nobles appalled at the idea of a Wallace alone.

Bruce would not then be at the centre of things – he had not been party to any of it so far, nor would he have been if he had not turned up on his own, dangling The Hardy’s family as security of his intentions and looking for the approbation of the other finely born in Wishart’s enterprise. Hal, dragged along in the Auld Templar’s wake, had wondered, every step of the way, what had prompted Bruce to suddenly become so hot for rebellion and Sim had remarked that Bruce’s da would not care for it much.

Bruce the son had not got much out of it. The Hardy had been grudgingly polite, the Stewart brothers and Sir Alexander Lindsay had been cool at best while Wallace himself, amiable, giant and seemingly bland, had looked the Earl of Carrick up and down shrewdly and wondered aloud why ‘Bruce the Englishman’ had decided to jump the fence. Now they were all glowering on the other side of the door, still wondering the same.

It was exactly what Wishart now asked.

‘If you have set your face against this enterprise and my choice of captain,’ Wishart grunted, slopping wine on his knuckles, ‘why are you here when your da is in Carlisle, no doubt setting out his explanations to Percy and Clifford of why his son has gone over to Edward’s enemies? I would have thought, my lord, that you would be bending your efforts against Buchan – and a body found in the woods.’

Hal leaned forward, for this was something he wanted to know as keenly – Bruce was young, his father’s son in every way until now, and his family had been expelled from their Scottish lands by the dozen previous Guardians, only just returned to them by Edward’s power. Why here? Why now?

Hal was sure the uncovered corpse had something to do with it, surer still that Wishart and Bruce shared the secret of it. He was also more certain than ever that he should not be here, mired in the midden of it all – how in the name of God and all His Saints had he become a rebel, sudden and easy as putting on a cloak?

He became aware of eyes, turned into the black, considered gaze of Kirkpatrick and held it for a long while before breaking away.

Bruce frowned, the lip pouted and the chin thrust out, so that the shadows turned his broad-chinned face to a brief, flickering devil’s mask – then he moved and the illusion shattered; he smiled.

‘I am a Scot, when all said and done. And a gentilhomme of your community of the realm, bishop,’ he answered smoothly, then plucked the prelate’s glass from his fat, beringed fingers and drained it, a lopsided grin on his face.

‘Besides – you have your fighting bear,’ he answered. ‘You need, perhaps, someone to point him in the right direction. To point you all in the right direction.’

Wishart closed one speculative eye, reached out and took the glass back from Bruce with an irritated gesture.

‘And where would that be, young Carrick?’

‘Scone,’ Bruce declared. ‘Kick England’s Justiciar, Ormsby, up the arse, the same way we did Heselrig.’

Hal heard the ‘we’ and saw that Wishart had as well, but the bishop did not even try to correct Bruce. Instead he smiled and Hal was sure some subtle message passed between the pair.

‘Aye,’ Wishart said speculatively. ‘Not a bad choice. To make sure of . . . matters. I will put it to the Wallace.’

He lifted the empty glass in a toast to Bruce, who acknowledged it with a nod, then smiled a shark-show of teeth at Hal.