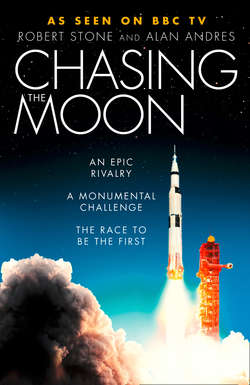

Читать книгу Chasing the Moon: The Story of the Space Race - from Arthur C. Clarke to the Apollo landings - Robert Stone - Страница 8

CHAPTER TWO THE MAN WHO SOLD THE MOON

Оглавление(1952–1960)

ON A THURSDAY evening in March 1952, viewers of NBC’s Camel News Caravan were introduced to a man who, in the next few years, would be celebrated as a national hero for ushering America into the space age, becoming his adopted country’s most widely recognized man of science. That only a decade earlier Wernher von Braun had overseen Adolf Hitler’s most ambitious weapons program is among the strangest and most confounding ironies of twentieth-century history.

It’s no surprise that von Braun’s affiliation with the Third Reich was not mentioned on the evening of his national TV debut. The handsome forty-year-old wore a tailored double-breasted suit and might have been mistaken for a crusading district attorney in a Hollywood film noir. But in no screen thriller did a DA ever speak in such a distinctly Teutonic accent or display the fantastic props that von Braun held onscreen. Viewers were told that these were models of space vehicles that would transport humans into the cosmos within a few years and bring an end to threats from Iron Curtain nations around the globe. Von Braun was on TV to launch a nationwide publicity campaign for the mass-circulation magazine Collier’s and, in particular, its latest issue, with a cover that proclaimed, MAN WILL CONQUER SPACE SOON!

In the spring of 1952, television sets were a fixture in one out of every three American households, an increase of 200 percent in the past twenty-four months. The new medium’s first users were predominantly upper-middle-class families living near cities with network-affiliate stations. For most of these viewers, von Braun’s spaceships were not a new sight. Adventure series such as Tom Corbett, Space Cadet and Captain Video were already competing against small-screen Westerns to capture the imaginations of young audiences. But von Braun’s NBC appearance that evening was intended for their parents, many from the generation of recent war veterans who were redefining America as it assumed its position as a global economic and military superpower. Indeed, the editorial introducing the new issue of Collier’s delivered an urgent Cold War warning: If the United States did not immediately establish its dominance in space, it would lose this high ground to the Soviet Union. Not only was America’s destiny in outer space but the nation’s security depended on mastering the science and technology to get us there.

Collier’s readers were introduced to von Braun as the technical director of the U.S. Army’s Ordnance Guided Missile Development Group. “At forty, he is considered the foremost rocket engineer in the world today. He was brought to this country from Germany by the U.S. government in 1945.” Further details about his wartime work were carefully omitted. He was pictured at the head of a table next to his first tutor and mentor in rocket research, Willy Ley. Shortly after the Peenemünde team arrived in the United States, Ley had cautioned friends to be wary of von Braun’s seductive charisma. By the early 1950s, von Braun’s charm, as well as his considerable political savvy and innate talent to inspire, had worked magic on his former enemies.

This wasn’t the first meeting on American soil of the two former colleagues. It was on a December evening in 1946 that Ley and von Braun had looked each other in the face for the first time in more than a decade and a half. Their post-war experiences in their adopted country had differed dramatically. Ley was the son of a traveling salesman; von Braun had been born into privilege, an aristocrat whose father was a politician, jurist, and bank official. Von Braun grew up with a sense of entitlement, which, when combined with his innate charisma, effortlessly opened doors. Physically, he could have been mistaken for a matinee idol; Ley once described von Braun’s appearance as “a perfect example of the type labeled ‘Aryan Nordic’ by the Nazis.” In affect and appearance, Ley, on the other hand, personified the “absentminded professor” stereotype. He wore thick-lens eyeglasses and spoke with a heavy accent, which peppered a discussion about UFOs with references to “flyink zauzers.” Nevertheless, Ley was a talented communicator with an ability to convey his curiosity and fascination about scientific subjects to audiences, which found his passions infectious. Unfortunately, he was less successful when attempting to find rocketry-related work in the United States in spite of his expertise, while von Braun charmed his way into new opportunities.

Their reunion had occurred when von Braun made his first visit to New York City, to attend an American Rocket Society conference, accompanied by his entourage of military minders. The presence of von Braun’s escort didn’t prevent Ley from extending an invitation to dinner at his apartment in Queens. Over glasses of wine, the two men talked until nearly 3:00 A.M., catching up on fifteen years of history during a discussion Ley later described as both tense and informative. Von Braun revealed the history of the Nazi rocket program and how he had come to lead it. However, he was less forthcoming about some crucial details that became more widely known only decades later.

Von Braun disclosed the circumstances behind his abrupt disappearance from the Verein für Raumschiffahrt in the fall of 1932. A captain in the German Army’s weapons department, Walter Dornberger, had personally recruited von Braun to research the development of liquid-fuel rockets as ballistic weapons. Dornberger set up a small lab at Kummersdorf, a secluded estate south of Berlin, and gave von Braun a stipend, a stationary rocket-engine testing stand, and an assistant. They imposed total secrecy on von Braun’s work since all Army-funded research was classified. While at Kummersdorf, the young scientist—then age twenty—was allowed to pursue his doctoral studies in physics and engineering at the University of Berlin. It was while he was at work on his dissertation that the Nazis removed Jewish professors and academics with suspected leftist political leanings, and burned books at the public rallies. Von Braun admitted to Ley that he had focused exclusively on his studies and was oblivious to the political significance of what was happening around him. When von Braun’s dissertation was finished, the German Army demanded it be titled “About Combustion Tests,” in an attempt to disguise the fact that it included detailed information about his liquid-fuel-rocket research at Kummersdorf.

Von Braun explained to Ley how by 1937 the German Army had financed the development of the world’s most powerful rocket of that time, a towering twenty-one-foot liquid-fuel missile, which they secretly launched from a remote island on the Baltic Sea. During Germany’s period of rearmament, von Braun said, he also worked on developing rocket-assisted airplane takeoffs for the air force, the Luftwaffe. Not long after, a competition ensued between the different branches of the German armed forces, with the Luftwaffe offering von Braun five million marks to establish a new facility for rocket development, and the Army coming up with six million more. The Army’s additional one million marks ensured that Dornberger would continue as von Braun’s superior and would exert greater control over the combined eleven-million-mark Luftwaffe-Army project. Von Braun couldn’t believe his good fortune. “We hit the big time!” he said, and was then tasked with finding the perfect location for his new facility.

Von Braun continued his story as he told Ley how he had searched for a remote secure location near a large body of water. Sensing the coming war, he also thought it should be a site strategically situated for future rocket launches against the Allies. His mother suggested Peenemünde, a relatively uninhabited pine-covered island on the Baltic, where his father used to go duck hunting. The Luftwaffe funded the luxurious facilities, and by 1938 the island had a brand-new town, a chemical-manufacturing facility, a power plant, and its own railway. At full capacity it would house twelve thousand employees.

As their conversation continued into the night, von Braun went on to vividly describe the first test of the A-4 rocket in October 1942. Listening attentively, Willy Ley attempted to mentally record as much information as he could. He had published Rockets: The Future of Travel Beyond the Stratosphere only two years earlier and realized the history section of his book was now unacceptably obsolete. Von Braun said the A-4—the rocket that became better known by its propaganda name as the V-2—had been designed to carry a one-ton warhead two hundred miles. Von Braun revealed that the first A-4 had been decorated with a painted insignia that depicted a long-legged nude woman with a rocket sitting upon the crescent moon, a reference to Fritz Lang’s Frau im Mond. The first test of the A-4 had gone far better than any of his team had expected. It reached an altitude of almost sixty miles. At a celebration after the launch, von Braun said Colonel Dornberger had looked around the room and remarked, “Do you realize that today the spaceship was born?”

After the A-4’s successful first flight, a number of guidance-system design problems remained unresolved and months of work lay ahead before the weapon could be deployed in the war. Some weeks later, von Braun and Dornberger were summoned to meet with Hitler to explain the production delays. They showed him a film of the first successful test. When the screening ended and the lights went up, Hitler displayed a sudden new enthusiasm for the A-4 program and talked of it as the superweapon he had been hoping for. Hitler immediately approved further research funding and conferred a professorship on von Braun—“the youngest professor in Germany”—and promoted Dornberger to major general.

The British had become aware of the activity at Peenemünde, however, and on the night of August 17–18, 1943, nearly six hundred RAF bombers dropped hundreds of tons of explosives on the facility. Almost seven hundred people were killed in the raid, most of them foreign prisoners who had been forced to work on the assembly of the early rockets. As a result of the raid, production for both the V-2 and the less complicated V-1 cruise missile was relocated to a distant underground facility. Development and testing of the V-2 missile continued at Peenemünde, but with a smaller workforce.

A crucial part of the story remained untold, however. The new hidden underground production facility was, in fact, built as part of the Dora-Mittelbau concentration camp in the Harz Mountains, more than three hundred miles southwest of Peenemünde. During the final two years of the war, thousands of slave laborers from the Soviet Union, Poland, and France were worked to death at Dora-Mittelbau while building thousands of rockets. A few grim details about the rocket-making facility appeared in American newspapers around V-E Day, but otherwise the full story detailing the extent of the horrors surrounding the V-2’s production went unreported in the United States for decades.

© NASA/Marshall Space Flight Center

Wernher von Braun photographed in the early 1950s holding a model of the V-2 rocket.

Despite holding a high position in the Third Reich, von Braun had been in serious danger. He told Ley how he had run afoul of Heinrich Himmler’s SS, which had been competing with the Army for control of the rocket program. After frankly admitting to Himmler that he preferred working under General Dornberger, von Braun was arrested by the SS. For two weeks he was held under suspicion of being a defeatist, a communist sympathizer, and a potential defector. His file even contained a report that during a private conversation he had confessed that if given a choice he would prefer to design spaceships instead of weapons, a comment that was considered dangerously anti-militarist. His release came only after General Dornberger made a personal appeal to Hitler’s minister of armaments and war production, Albert Speer, who, in turn, conveyed it to Hitler.

As Allied forces moved toward Berlin and the first V-2s began hitting targets in London and Antwerp in late 1944, slave laborers in Dora-Mittelbau’s massive tunnel facilities were assembling as many as six hundred V-2 rockets a month. But by March of the following year, the Russian Army was approaching Peenemünde, and von Braun and five hundred engineers and scientists fled south to the Bavarian mountains. Hiding in an alpine hotel, von Braun and Dornberger plotted their surrender to the Allies.

Two days before von Braun told his story to Ley, his picture had appeared in The New York Times in an article about the Operation Paperclip scientists. The Times reported that the technical knowledge of these “former pets of Hitler” would save American taxpayers an estimated 750 million dollars in research-and-development costs. Someone unimpressed by America’s new German brain trust was Ley’s friend, science-fiction author Robert Heinlein, who was disgusted when he learned that Ley had been “fraternizing with a Nazi.” Heinlein wrote to a mutual friend in the Navy that by spending the evening with von Braun, Ley had displayed careless expediency. As a result, Heinlein decided to withdraw his support for Ley’s efforts to find a government job.

Culturally, the new global superpower that had welcomed von Braun and the Operation Paperclip engineers still suffered from a pervasive inferiority complex. The superiority of the European tradition in the arts and sciences went largely unquestioned. To the citizens of a nation still less than two hundred years old, Wernher von Braun personified a cultured, well-mannered, soft-spoken European aristocrat, much like the characters played by Cary Grant, George Sanders, Claude Rains, or Paul Henreid in Hollywood movies. Typical of his upbringing, Von Braun was an accomplished musician who could play the “Moonlight Sonata” from memory. He was perfectly cast for the role he was to play in post-war America.

In Washington, America’s Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency carefully sanitized the troublesome personal histories of von Braun and other Operation Paperclip engineers, much as Hollywood publicists fictionalized the biographies of actors under the studio system. Von Braun arrived in the United States aware that his wartime management experience guaranteed him a position of importance—a position that until very recently had allowed him to be indifferent to the struggles of others or the ethical repercussions of his personal actions. Unlike most of his fellow space visionaries, von Braun was driven less by a personal desire to make a better tomorrow than by a personal ambition to accomplish something that no one had done previously.

Early in his career, von Braun realized that to achieve his goals, he had to become a persuasive salesman. He learned how to convince the key decision makers that his vision would confer to those in power precisely what he had deduced they most desired. To generals and dictators, he offered a promise of military superiority and national prestige; to those worried about threats from outside enemies, he promised security; to those searching for a sense of purpose and meaning, he promised a unique adventure and the fulfillment of our human destiny. Along with his persuasive salesmanship, he cultivated a rare talent to inspire others to do their best and to instill in them a sense of loyalty and dedication that seldom wavered.

It was while quartered with the other German rocket engineers at the Army’s Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas, that von Braun made a personal choice to become an evangelical Christian. His decision followed a visit to a modest white-framed church situated on a parched Texas lot, where, he later said, he came to realize for the first time that religion wasn’t something inherited like an heirloom but a personal commitment requiring effort and discipline. Von Braun’s conversion may have served to compartmentalize his European past from what lay ahead, as did his decision, at nearly the same time, to wed his eighteen-year-old cousin and bring her to Texas as part of his new life.

THE U.S. ARMY had shipped hundreds of crates containing the components for scores of confiscated German V-2s to the United States. Von Braun and his team restored their mechanisms and successfully launched them from a test range at White Sands, New Mexico, sending some as high as one hundred miles above the Earth. Later flights tried out a two-stage launch vehicle, with a second, smaller research rocket positioned on the nose of the modified V-2. After climbing to a height of twenty miles, the smaller rocket separated from the V-2 and, using its own engine, achieved a velocity greater than five times the speed of sound and ascending nearly two hundred fifty miles above the Earth.

But within the offices of the Pentagon, there was little interest in large rockets like the V-2, as either an offensive or defensive weapon. Its performance during World War II had proven the V-2 more effective as a weapon of psychological terror than destructive power. Von Braun’s work at White Sands had yielded interesting scientific information, but how it might be applied to Defense Department concerns was unclear.

The Cold War had become the dominant concern of those overseeing America’s defense planning, and space research had no role in it. Nevertheless, von Braun tried to think of ways in which he might persuade military decision makers to fund his space-flight research and development. He sought out the physicists at the national laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, who had developed the atomic bomb, with a proposal to marry an atomic warhead with one of his ballistic missiles: the genesis of the intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). But in the 1940s it was still assumed that conventional bomber aircraft were the most practical and effective way to deliver a heavy nuclear weapon to a target. Von Braun also outlined plans for a large orbiting military space station, which he argued could serve as a bombing platform capable of targeting any location on the globe and a unique surveillance outpost. It was an idea that he continued to refine and lobby for throughout the 1950s.

But his third and most ambitious idea to stimulate space funding didn’t depend on government defense strategies at all. Recalling how reading science fiction had fired his youthful imagination, von Braun decided to engage a new generation of space dreamers by writing a novel about the first voyage to Mars. Unfortunately for von Braun, the publishers who read the manuscript found his dialogue wooden and faulted the lack of a romantic subplot. When writing his manuscript, von Braun had emphasized the story’s technical accuracy; entertaining his reader was of secondary concern. In all, eighteen American publishing houses rejected it.

Four years after Arthur Clarke and the other officers of the British Interplanetary Society narrowly avoided being killed by the V-2 explosion, Clarke thought it time to exploit the experience to their advantage. He sent a letter to von Braun, offering him an honorary society membership. Von Braun graciously accepted, replying, “Despite the grief the work of me and my associates brought to the British people, [your invitation] is the most encouraging proof that the noble enthusiasm in the future of rocketry is stronger than national sentiments.” An exchange soon followed, in which von Braun sent Clarke some scientific details about the recent White Sands tests and Clarke invited von Braun to deliver a paper at an upcoming British Interplanetary Society conference in London.

In the immediate post-war years, von Braun’s U.S. Army minders kept him on a short leash. It was a time of heightened fear about Soviet spies operating within the United States, and the Army considered him a valuable asset. During his brief return to Germany to get married, the Army had von Braun under constant watch to prevent a Soviet kidnap attempt. But the Army had other worries as well. Von Braun gave a well-received speech to the El Paso Rotary Club in January 1947, but not long after, reports appeared in newspapers that revealed that some Operation Paperclip engineers had to be sent back to Germany after troublesome details about their Nazi past had come to light. Most press accounts stressed the Germans’ eagerness to work for the United States—their anti-communist sympathies were often cited—and indicated their hope to become American citizens. Nevertheless, the same month that von Braun addressed the El Paso Rotary, the president of the American and World Federations for Polish Jews said, “It is a sad reflection and insult to the consciousness of humanity [to welcome] these evil representatives of Nazi science … to this country with open arms.” For the next two years, von Braun maintained a modest public profile.

After the Germans had concluded their work with the refurbished V-2s at White Sands, the Army had few new projects to keep them occupied. There was scant military funding for additional rocket research, and their quarters at Fort Bliss were needed to house the Cold War’s growing roster of soldiers. The Army had to find a new permanent home for its restless and underutilized rocket specialists. In 1950, at the urging of Senator John Sparkman of Alabama, the Department of Defense moved the Army’s Rocket Branch of the Ordnance Department’s Research and Development Division to the recently shuttered Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama. It was here, near the Tennessee River, that the Fort Bliss rocket men relocated to buildings constructed a decade earlier for the manufacture and storage of chemical weapons and munitions. New signs announced the facility as the Army’s Ordnance Guided Missile Center. The thirty-five-thousand-acre site on which Redstone Arsenal had been built had already witnessed a great deal of history.

The fertile soil on the southern dip of the Tennessee River Valley had been home to Creek, Cherokee, and Chickasaw tribes prior to the arrival of the Euro-Americans, who forcibly removed all the native peoples during the 1830s and 1940s. For a few years before the Civil War, slaves worked the land’s large cotton plantations; however, during Reconstruction the land was subdivided into small tenant farms, many cultivated by the families of the recently freed. But after seven decades, the tenant farmers were forced to relocate when the Huntsville Arsenal and the Redstone Ordnance Plant were built on the land during World War II.

The German engineers who arrived in 1950 found the green landscape surrounding the Tennessee River a welcome change. After sandy and dry El Paso, Huntsville was somewhat reminiscent of Silesia, von Braun thought. When the engineers arrived, Huntsville’s population was only sixteen thousand, reflecting a post-war decline following the closing of the chemical-weapons facility.

Huntsville’s flagging economy began to rebound once the Army’s new Ordnance Guided Missile Center was established at Redstone Arsenal. The city’s new citizens brought a bit of European culture to northern Alabama, and local grocery stores began selling sauerkraut. Huntsville took on the air of a New England college town, albeit with a Dixie flavor: It founded a symphony orchestra, a ballet, and a Broadway Theater League and opened a newly expanded public library.

ONE OF THE most popular books in the new Huntsville library’s collection was Ley and Bonestell’s The Conquest of Space. In New York, the Hayden Planetarium created a popular show based on the book, which subsequently traveled to other cities. As a result of this collaboration, Willy Ley had become friendly with the planetarium’s chairman. In the course of a lunch conversation, Ley asked his friend why it was that the British Interplanetary Society could schedule annual conferences about human spaceflight but no such event had ever been planned in the United States.

Without much further discussion the Hayden’s chairman simply responded: “Willy, go ahead; the planetarium is yours.”

That seemingly minor exchange set in motion a sequence of events that would alter American attitudes toward space travel during the coming decade and turn von Braun into a celebrity of the early television era.

Less than six months after the Hayden Planetarium’s chairman gave his consent, Ley had assembled a roster of speakers for the First Annual Symposium on Space Travel, held, symbolically, on Columbus Day 1951. He conceived it as an event that would generate media interest and public awareness. Invitations were sent to every print and TV outlet with an office in the New York City area, including foreign publications. Among the two hundred attendees who heard talks on space medicine, space law, and upper-atmosphere science were two journalists from Collier’s magazine.

Collier’s assistant editor Cornelius Ryan was unimpressed with the report he received about the Hayden Planetarium conference from the two staffers who had attended. The Irish-born former war correspondent had little patience for all the recent talk about human space travel, believing the subject was more appropriate for children’s television than for a serious magazine. However, at the insistence of the managing editor, Ryan reluctantly attended a conference on space medicine in San Antonio. Collier’s also dispatched Conquest of Space artist Chesley Bonestell to sit in as well. After the first full day of presentations, Ryan was left confused and unimpressed.

Over cocktails, Ryan began a conversation with a tall handsome man also attending the conference. Grasping his highball glass, Ryan confessed, “They’ve sent me down here to find out what serious scientists think about the possibilities of flight into outer space.” As he gestured around the room he admitted, “I don’t know what all these people are talking about. All I could find out so far is that a lot of people get up to the rostrum and cover a blackboard with mysterious signs!” He said Collier’s was considering publishing a major cover story about space exploration, but he doubted readers would find anything presented at this conference of much interest.

His companion introduced himself as Wernher von Braun, and as he attempted to help Ryan understand the day’s presentations, he motioned for two others to join them. One was Fred Whipple, chairman of the Harvard University astronomy department, and the other was Joseph Kaplan, a scientist specializing in the study of the upper atmosphere. Over a lengthy dinner that lasted until nearly midnight, von Braun, Whipple, and Kaplan passionately took turns explaining why they believed humanity’s destiny lay in space.

The latest recipient of the von Braun charm offensive returned to New York a true believer. He convinced the magazine’s managing editor that a unique Collier’s-branded space symposium would generate publicity for the magazine and attract advertising dollars away from the emerging threat of television. Ryan insisted that von Braun should serve as Collier’s key expert, with additional articles written by other specialists from the New York and San Antonio conferences.

At that moment, von Braun and his engineers were spearheading the creation of the Redstone rocket, the Army’s first short-range ballistic missile. The Redstone was a bigger but less streamlined variation on the V-2, designed to carry a payload of nearly seven thousand pounds. Its rapid development was part of a newly unfolding rocket rivalry between two different branches of the armed services. At nearly the same time that the Army decided to develop the Redstone, consultants for the U.S. Air Force began work on their own intercontinental-ballistic-missile development program, which would eventually reach fruition with the Atlas. Though designed to deliver munitions, both the Redstone and Atlas would become far better known to the general public a decade later for their role as the vehicles that transported the first Americans into space.

Having brought von Braun’s entire team to Huntsville, the Army was now more comfortable with him entering the public spotlight. He had not spoken at either of the two American space conferences during the autumn of 1951, though other Operation Paperclip Germans—Dr. Hubertus Strughold and Heinz Haber—had delivered papers. Strughold had risen to prominence as a leading researcher on the physical and psychological effects of human spaceflight, but details about his past had been deliberately obscured. Indeed, it would be another four decades before allegations of his complicity in notorious Nazi-era human medical experiments were widely published. By 1951, public objection to government employment of the Paperclip scientists and engineers had largely subsided, though the Germans’ hopes for American citizenship would remain unfulfilled for a few more years.

In April 1951, journalist Daniel Lang published an extended profile of von Braun in The New Yorker. A former war correspondent who had covered World War II in Italy, France, and North Africa, Lang was intrigued by the ethical choices faced by men of science during the Cold War. Lang described von Braun’s personality as “exuberant rather than reflective” and thought he comported himself like “a man accustomed to being regarded as indispensable.” Unlike the reticence he displayed in later interviews, von Braun was unguarded with Lang, even confessing, “Working in a dictatorship can have its advantages, if the regime is behind you…. We used to have thousands of Russian prisoners of war working for us at Peenemünde.” The profile also revealed that 80 percent of the Germans working at Redstone Arsenal had been members of the Nazi Party or affiliated organizations and that von Braun had been a party member. Pressed by Lang to address the morality of his decision to work for the German Army, von Braun explained, “We felt no moral scruples about the possible future abuse of our brain child…. Someone else would have done the job if I hadn’t.” After the New Yorker profile appeared, von Braun became more cautious when talking to the press.

At the end of the year, Collier’s gathered a symposium of space experts in the magazine’s New York office, where von Braun was joined by Ley, Whipple, Bonestell, and others. In conjunction with the magazine’s forthcoming issue, Collier’s commissioned a series of detailed full-color illustrations of giant spacecraft reaching orbit and showing how humans would live and work in space. These were based on plans and sketches drawn up by von Braun and his team in Huntsville. Von Braun also assigned Gerd de Beek, a former Peenemünde staffer now at Redstone, to construct scale models of the huge rocket and space station. It was de Beek who had painted the Frau im Mond insignia on the first successfully launched A-4 in 1942.

In the weeks before the March publication date, the Collier’s staff concluded that von Braun was such an asset that they chose him as their spokesperson to promote the special issue at media events. After his national television debut on the Camel News Caravan, von Braun appeared several more times on the new medium within twenty-four hours. In Manhattan he traveled from one network broadcast studio to another for scheduled live interviews on the most popular programs. In the morning he was on the Today show on NBC; by the afternoon he was in a CBS studio chatting with entertainer Garry Moore. He even put in an appearance at the end of the day during a broadcast of ABC’s children’s adventure series Tom Corbett, Space Cadet. Whenever he appeared, he brought along de Beek’s models to illustrate his argument.

After working nearly seven years with little national recognition, von Braun was exuberant that his American moment had arrived. “I’m tickled to death about this TV and radio business,” he wrote Ryan. “Space rockets are hitting the big time!”

The Collier’s issue looked like nothing that had been seen previously in a mass-circulation general-interest magazine. Bonestell’s color illustrations provided eye-catching visions of space vehicles heading into orbit and space stations under construction. Equally impressive were the magazine’s cutaway diagrams showing the interiors of von Braun’s huge rocket and the rotating space station. The attention to detail in these images conveyed a convincing sense of accuracy, even though they were based on plans that were entirely imaginary. With a circulation of three million copies and an estimated reach of twelve to fifteen million readers, that single issue of Collier’s was believed to have been seen by 8 to 10 percent of the American public.

The Collier’s publicity campaign included department-store window displays and posters on buses, subways, and newsstands. The cumulative effect not only promoted the magazine, it suddenly transformed von Braun into the world’s most visible public proponent for space exploration. Collier’s introductory editorial emphasized space as a national defense and security concern, though military implications were downplayed in the articles. In von Braun’s feature article, “Crossing the Last Frontier,” he made reference to his orbiting “atomic bomb carrier” space station, but apocalyptic scenarios were kept to a minimum. Not that Collier’s was averse to exploiting Cold War fears to sell issues; two years previously they had commissioned Bonestell to paint disturbing scenes of Manhattan consumed by an atomic mushroom cloud. But with their space issue, Collier’s presented a more optimistic technological vision of the future, which promised both adventure and a new domain for human exploration. It was a welcome relief from concerns about nuclear proliferation, Soviet espionage, and the ongoing Korean stalemate.

So favorable and resounding was the reader and media response to that Collier’s immediately began planning additional space-themed issues. The next one hit newsstands October 1952 and featured articles about the first human voyage to the Moon. Von Braun continued to make public appearances, such as an extended segment on the only network TV program about science, The Johns Hopkins Science Review, which broadcast three separate thirty-minute episodes discussing the Collier’s series.

Culturally, the Collier’s issues had prompted a significant shift in public attitudes toward human spaceflight: The subject was no longer ridiculed or approached with embarrassment. At the San Antonio conference the previous year, the organizers had been reluctant to use the word “spaceflight” in the event’s title, for fear that it would diminish its seriousness. After spring 1952, politicians speaking about space travel seldom encountered the derision David Lasser had experienced on the floor of the House of Representatives a decade earlier.

ON THE EVENING of July 9, 1952, CBS newsman Walter Cronkite sat in a wood-paneled studio in Chicago, covering the opening of the Republican National Convention. It was a decisive moment for the young journalist as well as for the country. Cronkite was anchoring the first live network broadcast of an American political convention. The GOP campaign had begun in New Hampshire the same week that von Braun made his TV debut. Now the field of candidates had narrowed to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Ohio senator Robert Taft, and California governor Earl Warren.

The former speaker of the House, Joe Martin, Jr., gaveled the convention into session, and in a speech watched by millions, Martin attacked the Democrats in power as “disciples of a dead-end economy” who offered the youth of America nothing more than a “road to nowhere.” Martin then segued to offer a more optimistic vision of the future, and when doing so he appeared to have in mind a recent national magazine. “We have an entire new world about to unfold!” Martin promised. “I listen to the words of scientists and engineers…. They are optimistic! They are visionary beyond our fondest dreams! They say that science and technical skill are uncovering new horizons that all but defy the imagination.” He described new advances in medicine, power, and transportation. Then Martin turned to the heavens. “Travel in space! I mean interplanetary travel—in our solar system—no longer is the figment of a cartoonist’s imagination. It is on the verge of reality! Who knows what wonders lie beyond the limit of our atmosphere, what new worlds will open to us?”

A foreigner who had arrived in the United States on the Queen Mary a few days earlier watched the convention with great interest on the television set in his hotel room. Arthur C. Clarke was in America to promote the publication of his newest book of nonfiction, The Exploration of Space. The judges of the Book-of-the-Month Club had chosen it as a featured selection in the wake of the Hayden Planetarium conference and the enthusiastic response to the Collier’s issue.

Clarke sat up and listened to Joe Martin with astonishment. A politician was on national TV giving a speech that contained passages that could have been written by Clarke himself. “I didn’t expect the Republican Party to take official cognizance of the topics the science-fiction writers love to mull over,” he recalled later. He listened as Martin talked of smart “electronic computing machines” and wrist radios utilizing “a new invention no bigger than a postage stamp, called the transistor.” He was delighted. “After that, nothing could drag me away from the convention.”

This was only the second trip Clarke had taken outside of the United Kingdom, and as he traveled the United States, others aspects of 1950s America caught his attention. At the invitation of Ian Macaulay, a fanzine editor whom he had met at a science-fiction convention, Clarke traveled to Atlanta, Georgia. At that moment Macaulay was active in the fight for civil rights, organizing to end segregation in schools and public transportation and working to increase African American voter registration. Macaulay’s activism prompted some lengthy late-night discussions during which Clarke learned more about America’s long history of racial inequity.

Prior to coming to the United States, Clarke had never met any black people. He stayed with Macaulay again in Atlanta the following year, and during his return visit he was at work on the final pages of his novel Childhood’s End. In the book’s conclusion, an adventurous scientist named Jan Rodricks is selected by representatives of an advanced extraterrestrial civilization to witness the transformation of the human race into a higher form of life: a collective cosmic entity. Clarke’s decision to make Rodricks—his fictional representative of all mankind and “the last person on Earth”—an astronomer of black African descent was a bold and politically provocative choice for 1953.

Since reading a short story about a sympathetic alien in a 1934 issue of Wonder Stories, Clarke had been fascinated by science fiction’s potential to evoke empathy for alien characters and convey to readers the viewpoint and values of those from other cultures. During its formative decades, the genre’s predominantly male readership was hungry for escape from the mainstream culture and curious about emerging technologies and new ideas. Many science-fiction readers were intelligent yet socially marginalized in some way due to a variety of reasons, such as ethnicity, sexuality, religion, or race. Plus, conventional society’s habit of ostracizing and calling those with an interest in technical or intellectual subjects “nerds” or “eggheads” was familiar to a sizable segment of the genre’s readership. Not surprisingly, therefore, science-fiction readers often identified with the alien.

By the early 1950s, some science-fiction authors had begun using mass-market paperbacks as a literary vehicle to subtly question conventional attitudes about race and sexuality. The cover illustration on a 1952 book of short stories by Robert Heinlein featured the first visual depiction of a black astronaut, even though no such character was specifically described within the book, and publishers’ sales directors at the time expressly asked illustrators not to include African Americans on book covers, since it was assumed this would hinder sales south of the Mason–Dixon Line. A year later Weird Fantasy, a science-fiction comic book, published an allegory on American segregation in a story about an emerging civilization on a planet where orange robots are accorded privilege over the less entitled blue robots. In the story’s kicker ending, the space-suited emissary, who sits in judgment of the planet and denies its application for admission to a galactic republic, is revealed to be a black astronaut.

Robert Heinlein, who had also challenged social preconceptions about masculinity and femininity, wrote Tunnel in the Sky in 1955. In the young-adult novel, the race of the central protagonist is not overtly defined, but there are hints that he is black. Heinlein confessed that he used this literary device in an attempt to disarm his white readers, hoping that in the course of the narrative they would gradually come to realize the protagonist’s race after feeling empathy and identifying with him.

Writing in an essay for The New York Times shortly after his visit to Atlanta, Clarke addressed this issue as part of a larger defense of science fiction as literature. “Interplanetary xenophobia [in earlier science fiction] has given place to the idea that alien forms of life would have as much right to their points of view as we have. Such an attitude … can obviously help spread the idea of tolerance here on Earth (where heaven knows it’s needed).”

THE SUMMER THAT Arthur Clarke returned to the United States and was finishing the manuscript of Childhood’s End, he finally met Wernher von Braun, when both were guests at the Washington, D.C., home of the American Rocket Society’s president. In a lengthy diversion from a dinner conversation about humanity’s future in space, Clarke described his love of scuba diving and explained that it was an effective way to simulate the experience of being weightless in space. He then vigorously urged von Braun to take up the sport for the same reason, which von Braun did only a few weeks later, remaining an active diver for most of his life.

Even while overseeing the development of the Redstone rocket and working on a top-secret plan to quickly and inexpensively launch the first satellite into orbit, code-named Project Orbiter, von Braun continued his public advocacy for human spaceflight. An unexpected opportunity arose directly as a result of the Collier’s publications, just as the magazine released its eighth and final space-themed issue, featuring a description of the first human voyage to Mars. In early 1954, Hollywood came calling, in the person of Walt Disney, who was interested in producing a series of well-financed hour-long documentary films based on the magazine series. Disney was in the midst of creating a new prime-time TV program, Disneyland, which would mix recycled older content and new programming in order to promote another new venture, his California theme park, scheduled to open in 1955.

At the suggestion of one of his top animators, Ward Kimball, Disney approved three space-related “Tomorrowland” episodes adapted from Collier’s articles. The first episode, “Man in Space,” had Ley, von Braun, and Heinz Haber discussing rocketry history, orbital science, and the physical challenges facing humans during spaceflight, before concluding with an animated look into the near future as humans first entered space. Disney’s choice to feature three onscreen experts with distinctive German accents became an issue of concern within the studio prior to filming, until it was deemed that their authenticity was more valuable than any possible negative associations. The history portion of the program included World War II–era footage of V-2 launches, yet there was no mention of Nazi Germany’s part in rocket development; the V-2 was merely referred to reverently as “the forerunner of spaceships to come.” Among the featured experts, it was von Braun who commanded the viewer’s attention. Looking into the camera, he confidently asserted, “If we were to start today on an organized and well-supported space program, I believe a practical passenger rocket can be built and tested within ten years.”

© NASA/Marshall Space Flight Center

Walt Disney and Wernher von Braun in 1955 collaborating on “Man in Space,” one of three space exploration–themed episodes broadcast on Disney’s weekly television series in the 1950s. The programs were seen in more than a third of American households, including the White House, where President Dwight Eisenhower tuned in.

“Man in Space” premiered in the spring of 1955. Forty million households—more than a third of the American viewing public—watched the broadcast on their black-and-white televisions. Polling conducted that year revealed that nearly 40 percent of Americans believed “men in rockets will be able to reach the Moon” before the end of the century, a figure that had more than doubled in six years. Once again, von Braun’s space advocacy had political repercussions. One viewer who saw “Man in Space” lived at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, and after the broadcast Disney received a request from the Eisenhower White House for the loan of an exhibition print of the program so that it could be screened for Pentagon officials.

In nearly all of his entertainment, Disney promoted commonly accepted traditional American values. Though he kept his personal political attitudes out of the spotlight, Disney’s were conservative and anti-communist. Von Braun’s association with Disney therefore subtly bestowed an imprimatur of American respectability on the former official of the Third Reich. And in a final act of assimilation, a month after “Man in Space” aired, von Braun and more than one hundred other Germans working at the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville appeared in a newsreel taking an oath of allegiance as they became U.S. citizens.

Von Braun was also celebrated in American public schools, many of which had recently introduced new audio-visual equipment into the classrooms. The Disney studio actively licensed 16mm exhibition prints of “Man in Space” as an entertaining teaching aid. Disney published a teacher’s study guide to use in conjunction with the screening, which featured von Braun’s photo on the cover and suggested classroom discussion questions such as “How likely is it that the present barriers between nations will tend to break down as contacts with other planets develop?”

Von Braun’s onscreen presence in the Disney programs coincided with his appearance in another far less visible film. Released in late 1955, the low-budget black-and-white Department of Defense film Challenge of Outer Space recorded an “officers’ conference” in which von Braun addressed a classroom of officers from various branches of the armed services. The content of his presentation paralleled the Disney films—and even included Collier’s illustrations. However, von Braun approached it almost entirely in terms of Cold War military superiority, something that was never mentioned in the “Man in Space” program. When discussing his space station, von Braun described it as something of “terrific military importance both as a reconnaissance station and as a bombing platform” with “unprecedented accuracy.”

Seated in front of an American flag, von Braun answered rehearsed questions from the officers, such as “Dr. von Braun, can you explain why it would be easier to bomb New York from a satellite than from a plane or a land-launched guided missile?” His response to such sobering questions was in marked contrast to his demeanor in the Disney production. He didn’t resort to colorful language to appeal to his listeners’ sense of wonder or innate desire to explore the unknown; there were no mentions of a “Columbus of space” or allusions to humanity’s evolutionary leap when first entering the cosmos. From his past experience, von Braun well knew that delivering his message to a room of grim-faced men wearing campaign ribbons necessitated very different rhetoric. He framed his talk entirely in terms of adversarial conflict and achieving strategic advantage and concluded with a note of warning: “The Russians are already hard at work, and if we are to be first, there is no time to lose.”

IN THE SPRING of 1955, the Eisenhower White House approved a proposal for the United States to orbit the world’s first satellite during the upcoming scientific International Geophysical Year. Modeled on International Polar Years of the past, the IGY would involve scientists from forty-six countries taking part in global geophysical activities and experiments from July 1957 through December 1958. The Soviet Union was believed to be on the verge of announcing its own satellite program, so the United States was attempting to stake its claim as well.

Very real Cold War concerns lay behind what appeared to be a purely scientific initiative. Since the beginning of the escalating nuclear-arms race, the two superpowers had been seeking a method to monitor the progress of their opponent’s weapons programs and their compliance with international agreements. Rather than using a high-altitude spy aircraft, which ran the risk of being shot down, the influential global-policy think tank, the RAND Corporation, proposed a space-age alternative: an unpiloted orbiting observational satellite that would either transmit video images or return exposed film reels via automated reentry capsules.

President Eisenhower believed that if a scientific research satellite was placed in an orbit that passed over the airspace of a Soviet Eastern Bloc country, this action would establish a precedent for orbital overflight, thus opening up space for observational reconnaissance. But from a diplomatic perspective this was an unsettled matter of international law. Eisenhower listened to other advisers, who cautioned that if the United States became the first to orbit an object over another nation’s sovereign territory, it risked international condemnation. They thought it wiser for the United States to hold off being first.

Von Braun’s secret Project Orbiter proposal was vying against two alternative plans, developed by the Air Force and the Navy. Orbiter was generally acknowledged to be the most sophisticated, practical, and reliable of the three proposals, but it was the Naval Research Laboratory’s Project Vanguard that got the official nod in late July 1955 when the White House made its announcement. (The projected launch wouldn’t occur until late 1957 or 1958.) Von Braun believed Project Orbiter had lost out to the Navy specifically because he had been involved. He wondered whether professional jealousy, his recent celebrity status, and prejudice about his German past, combined with the ever-present interservice rivalry, had contributed to his satellite’s rejection. Von Braun was so sensitive about reports of antagonism against him in Washington that when he learned that Disney’s publicists were planning to promote a rebroadcast of “Man in Space” with an ad line suggesting that the TV show led directly to the White House’s recent action, he vehemently implored them not to do so, fearing that some in Washington would assume he was using his Hollywood connections to take credit. “The statement would hurt the cause far more than it would help,” he told Disney’s producer.

In fact, a more important factor was involved in the selection. Giving the project to the Naval Research Laboratory was intended to deemphasize military and strategic implications, since the lab already had a reputation for conducting basic scientific research, unlike the Ordnance Guided Missile Center at Redstone Arsenal. The Navy planned to use modified research rockets with an established pedigree from past scientific-research experiments. In contrast, the Army intended to use a modified Redstone, which had been expressly developed to carry a nuclear explosive.

A memo written by Eisenhower’s secretary of defense, Charles Wilson, clarifying the nation’s missile-development responsibilities, only made matters worse for von Braun’s team. Wilson gave the Air Force responsibility for all future land-launched space missiles and limited the Army’s work to surface-to-surface battlefield weapons with a range of less than two hundred miles. At Redstone Arsenal and in the city of Huntsville, morale plummeted.

Four days after the White House’s announcement of Project Vanguard, Soviet space scientist Leonid I. Sedov addressed reporters at his country’s embassy in Copenhagen, where the annual congress of the International Astronautical Federation was being held. Much as the White House had expected, Sedov announced that the Russians would possibly launch a satellite in the next two years. When asked by a journalist about any German rocket specialists employed in Russia, Sedov adamantly insisted that none were working there.

Sedov’s assertion was largely correct, despite published rumors to the contrary. The full story didn’t emerge for decades. Joseph Stalin had personally authorized that nearly five hundred of the remaining rocket engineers from Peenemünde be forcibly transported to Russia in 1946. They were confined to isolated communities with little more than standard amenities, where they were subject to constant surveillance and the enmity of their Russian counterparts.

The Soviet Union’s closest equivalent to von Braun was Sergei Korolev, a Ukrainian-born engineer and strategic planner who, despite having spent six years in one of Stalin’s gulags, had risen to prominence as the chief rocket designer. Korolev distrusted the German engineers living in Russia, fearing that if they attained positions of importance they could possibly thwart his own ambitions and undermine the authority of his handpicked team of designers. Nevertheless, by the mid-1950s, and after wasting years working on projects of little importance, most of the captured Germans were finally allowed to return to the West.

A RINGING PHONE in the darkness immediately woke him. Arthur Clarke reached for his glasses and rose from the bed in his Barcelona hotel room to catch the call. The man’s voice on the other end of the line said he was calling from London. It was a journalist from the Fleet Street tabloid the Daily Express, requesting a quotation in reaction to the breaking news. The reporter informed Clarke that minutes earlier the Soviet news agency, Tass, announced that Russia had successfully launched an artificial moon weighing 184 pounds into orbit around the Earth.

It was approaching midnight on October 4, 1957. Clarke was in Spain to attend that year’s International Astronautical Federation conference, and the call from London placed him in a privileged position among those who had arrived. Generalissimo Francisco Franco’s regime maintained an international news blackout; nothing appeared in newspapers or on the radio until it had been cleared for public release. Most of the other conference delegates remained ignorant of the Soviet Union’s triumph until those arriving late brought the news of the outside world with them. But within a few days everyone knew a new Russian word, “Sputnik,” meaning “fellow traveler.” The provocative response that Clarke gave to the reporter that night received attention in newspapers around the world as well: “As of Saturday the United States became a second-rate power.”

Clarke’s words did not sit well with William Davis, an American Air Force colonel. “I heard that and I didn’t like it! Space is the next major area of competition. If this one is lost, we might as well quit.” Colonel Davis suggested the United States should counteract the Soviet propaganda by readying its own space vehicle, with a human on board.

Missing from the Barcelona conference was Wernher von Braun. It was still Friday evening in Huntsville when a British journalist called his office at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency, the successor to the Ordnance Guided Missile Center. Von Braun had feared this day would come, and his sense of disappointment was mixed with anger. He had no doubt that had the United States government given him the opportunity, he would have placed the first artificial satellite in orbit.

At a press conference a few days later, President Eisenhower congratulated the Soviets but dismissed the idea of a race with Russia. He emphasized that both superpowers were engaged in an international program of scientific research. Eisenhower attempted to explain the Soviets’ success by casually noting that “the Russians captured all the German scientists at Peenemünde,” a remark that astounded many in Huntsville, as it was an outright lie. Unstated by Eisenhower was his relief that Russia had established the controversial precedent of orbital overflight. In the future, neither the Soviets nor other nations could voice their diplomatic objections when the United States eventually orbited its planned surveillance satellites.

The American media’s reaction to Sputnik was far less measured than the president’s. Columnists bemoaned the shocking loss of national prestige and criticized Eisenhower’s blasé reaction as lack of leadership. Opposition politicians appeared on television, expressing fear that the Soviets might use their powerful rockets to position a nuclear sword of Damocles above any nation.

Overshadowed by the news of Sputnik was another event at the Barcelona astronautical conference that captured the Cold War zeitgeist. Dr. S. Fred Singer, a young Austrian-born physicist noted for his work in cosmic radiation, was there to deliver a provocative paper. One of von Braun’s Project Orbiter colleagues and a leading member of the American Astronautical Society, Singer had also cultivated a talent for getting his name into print by fearlessly saying things his more prudent scientific colleagues would avoid.

Singer’s paper was titled “Interplanetary Ballistic Missiles: A New Astrophysical Research Tool” and argued in favor of exploding thermonuclear bombs on the Moon as a way to conduct scientific research. It was an idea that, he said, was “not only peaceful, but also useful, and, therefore, worthwhile.” This proposal, he believed, might lead to other experiments, such as exploding thermonuclear devices on the planets or an attempt to create a new star. But more immediately, Singer suggested, this initiative would promote world peace, as “the H-bomb race between the big powers would then be reduced to the much more tractable problem of seeing who could make the bigger crater on the Moon.” He was especially excited by the possibility of rearranging lunar geography. “The idea of creating a permanent crater as a mark of man’s work is an appealing one,” he said. “One is left with a nice crater on the Moon which is unnamed and therefore provides unique opportunities for perpetuating the names of presidents, prime ministers, and party secretaries.”

The Soviet delegates sitting in the lecture hall listened to Singer’s proposal with understandable astonishment and outrage. However, Singer later remarked that the Soviet reaction to his paper was “blown out of proportion.”

As Sputnik dominated the headlines, newspapers gave less attention to the big story out of Little Rock, Arkansas, where a week earlier President Eisenhower had ordered 1,200 members of the Army’s 101st Airborne Division to assist with the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School. The day before Eisenhower’s order to mobilize the troops, more than a thousand white protesters had rioted to prevent nine black students from attending the school. After Sputnik was launched, Radio Moscow seized upon an opportunity to shame the United States for hypocritically calling itself “the land of the free”: It alerted its global listeners to the exact moment when the satellite would pass over Little Rock, news that was specifically intended to be heard in the emerging independent nations of Africa.

Incensed that he and his new boss at Huntsville’s Army Ballistic Missile Agency, General John Medaris, hadn’t been given an opportunity to ready a modified Redstone rocket to launch a swift response to Sputnik, von Braun covertly made his case in the media, despite having received orders from Washington not to make any public comments. Magazine features called him “The Prophet of the Space Age” and “The Seer of Space,” portraying him as the brilliant visionary whose bold ideas had been ignored by petty bureaucrats, unimaginative military officials, and cowardly politicians. And knowing that nothing motivated people as powerfully as fear, von Braun evoked the specter of atomic annihilation, arguing that it was imperative that the United States establish its superiority in space if the nation was to survive.

Eisenhower became increasingly irritated by von Braun’s arrogance, celebrity status, and self-serving pronouncements. In fact, the president’s growing frustration with von Braun likely accounted for his wildly inaccurate comment at his press conference about the Russians having all the German scientists. If it had been intended to belittle von Braun’s reputation and public profile, it backfired badly.

The media panic only increased when in early November the Soviets orbited Sputnik 2. A much heavier satellite, it carried the first living creature on a one-way trip into orbit, the photogenic husky-terrier mix, Laika. NBC’s Merrill Mueller, a reporter who had covered D-Day, the Battle of the Bulge, and the bombing of Hiroshima, grimly faced the television camera as he told viewers, “The rocket that launched Sputnik 2 is capable of carrying a ton-and-a-half hydrogen-bomb warhead.”

Democrats with eyes on the 1960 elections, and possibly the White House, added their dire voices to the chorus of doom. Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson announced that this was the last chance to save Western civilization from annihilation, while Senate majority leader Lyndon Johnson compared Sputnik to a cosmic Pearl Harbor, warning the nation that we “must go on a full, wartime mobilization schedule.”

Taking von Braun’s lead, Johnson forecast a sinister future vision that would delight the heart of a James Bond supervillain: “Control of space means control of the world,” he declared. “From space, the masters of infinity would have the power to control the Earth’s weather, to cause drought and flood, to change the tides and raise the levels of the sea, to divert the Gulf Stream and change temperate climates to frigid.”

Eisenhower scoffed at all the apocalyptic rhetoric, as well as at those who offered a variation on Fred Singer’s idea that the United States should respond to the Soviet Union’s presence in space by sending a rocket to the Moon armed with a warhead. In response, Eisenhower said he would rather have one nuclear-armed short-range Redstone rocket than an expensive and impractical moon rocket. “We have no enemies on the Moon,” he declared.

On Capitol Hill, Lyndon Johnson invited von Braun and General Medaris to testify before a Senate preparedness subcommittee inquiry. Johnson not only recieved the media exposure he desired, but the pair from Huntsville put the White House on the defensive with a few well-crafted lines for the newsreel and television cameras. “Unless we develop an engine with a million-pound thrust by 1961,” Medaris warned, “we will not be in space—we will be out of the race!” Von Braun raised the specter of a hammer and sickle hanging in the heavens, cautioning that the country was “in mortal danger” if the Soviets conquered space. “They consider the control of space around the Earth very much like, shall we say, the great maritime powers considered the control of the seas in the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries. And they say, ‘If we want to control this planet, we have to control the space around it.’ ”

The country heard them testify to how the Army’s readiness had fallen victim to petty armed-service rivalries, bureaucratic lassitude, and indecisiveness, a situation that Johnson called “nothing short of disgraceful.” Von Braun once again hypnotized the press, particularly a New York Times journalist who described him as a “blonde, broad shouldered and square-jawed … youthful-looking German scientist” who “drew many sympathetic laughs as he smilingly grappled with questions.”

The nation’s attempt to rid itself of Sputnik anxiety came on a morning in December 1957, barely two months after the shocking news from Moscow. Journalists at Cape Canaveral all had their binoculars focused on Launch Complex 18. There had been no official announcement, but word had spread among the newsmen that this was the likely day; sources at the local motels, restaurants, and bars all said something was being planned for that morning.

Shortly before noon on December 6, a cloud of white smoke appeared at the base of the U.S. Navy’s Vanguard rocket as it began to move upward into the sky. CBS News’s Harry Reasoner observed the launch from a privileged position on the porch of a nearby beach house. At the first sign of smoke he shouted, “There she goes!” His assistant, who was inside the house, on the phone with the network’s New York newsroom, immediately conveyed the word. Once the message had been received, Reasoner’s New York colleague promptly put down the phone to get the news on the air. But by that moment Reasoner was shouting, “Hold it! Hold it!” as he watched the Vanguard fall back on the pad and collapse into an expanding fireball, its tiny satellite toppling out of its nosecone. CBS had beaten ABC and NBC in broadcasting the news from the Cape but had incorrectly reported that the launch had gone well.

The shock of the failure was somewhat reduced by the fact that pictures of the explosion hadn’t been broadcast on live television. But the humiliating film of Vanguard’s end was shown repeatedly later in the day, often in slow motion. In the days that followed, the Air Force Missile Test Center chose to impose tighter media regulations, going so far as to prohibit binoculars and cameras on the nearby beaches.

In the wake of the failed launch, General Medaris and von Braun struggled to find their opportunity. Their Jupiter rocket, built in four stages so as to carry a satellite into orbit, was assembled later that month. But when it came to scheduling an available launch date at Cape Canaveral, the Huntsville team had to compete with their rivals, preparing a second Vanguard. The Navy rocket went through four different countdowns in January, but all were canceled due to technical difficulties or bad weather. The Army was alloted only three days —January 29, 30, and 31—to get Jupiter off the ground.

High winds canceled any possibility of a launch on the first two days, but at the last available opportunity, at 10:48 P.M. on January 31, 1958, Jupiter lifted off. NBC News used a motorcycle courier, a light airplane, and a police escort to rush their film of the launch to an affiliate station in Jacksonville, where it was processed and broadcast nationally within ninety minutes.

By the time the film was ready, von Braun, University of Iowa astrophysicist James Van Allen, and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s William Pickering were holding a midnight press conference in a small camera-packed room at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington. Pickering’s JPL, in Pasadena, had designed and built Jupiter’s payload, the Explorer 1 satellite; Van Allen was in charge of the United States’s International Geophysical Year satellite program. Basking in triumph before a bevy of reporters, the trio held above their heads a full-size replica of Explorer, in a pose that became an iconic press photo.

In Huntsville, few were watching television at that late hour. The town that had seen its population triple in the eight years since the Army brought its rocket-and-missile center to northern Alabama had informally renamed itself “the Rocket City.” Led by a call from its mayor broadcast over the local radio station, Huntsville’s police sounded squad-car sirens and honked horns as citizens gathered downtown to celebrate with cheers of vindication and jubilation. Close to midnight, thousands gathered in the town’s Courthouse Square, which had been watched over by a granite statue of a Confederate soldier since 1905, erected and dedicated a few months after a notorious lynching on the same spot. The crowd held signs reading SHOOT FOR MARS!, OUR MISSILES NEVER MISS!, and MOVE OVER MUTTNIK!

© NASA/Marshall Space Flight Center

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s William Pickering, physicist James Van Allen of the University of Iowa, and Wernher von Braun celebrate the launch of Explorer I, the first American satellite, at their midnight press conference in Washington, D.C., on January 31, 1958.

The mayor joined the rowdy celebration, lighting skyrockets and ducking exploding firecrackers. A Life magazine photographer pointed his Speed Graphic camera at the gleeful crowd, which hoisted high an effigy of former defense secretary Charles Wilson; images with unsettling reminders of the town’s past. After his 1956 memo restricting the Army’s missile program, Wilson had become the most hated man in Huntsville, and he was now widely blamed for allowing the Soviets to be first in space. As the effigy was torched, the revelers waved American and Confederate flags and shouted, “The South did rise again!”

Von Braun was the man of the moment. His face was on the covers of Time and Der Spiegel. Eisenhower invited him to a White House state dinner. When he appeared in Washington, overflow crowds of journalists and photographers would attend, yet never were there any questions about his war years. Congressmen requested that he pose for photographs with members of their family. As a Capitol Hill session on space appropriations was breaking up, one congressman was even heard asking, “Dr. von Braun, do you need any more money?”

Von Braun signed with a speakers’ bureau and commanded as much as two thousand five hundred dollars for an appearance. Columbia Pictures and a West German studio commenced discussions to determine whether his personal journey from Nazi weapons engineer to Cold War American hero might serve as the basis of a successful dramatic film.

The attention and adulation given von Braun and his Huntsville team neglected one important German without whom Explorer would never have orbited. Hermann Oberth had joined the German rocket community in Huntsville, after von Braun had reached out to his former mentor and offered him work in the Army Ballistic Missile Agency’s research-projects office. But Oberth hadn’t been able to stay current with the ever-changing technology, and as a German citizen, he was restricted from reading classified information. He worked alone on projects of his own design, but his research produced little of consequence. Oberth’s prickly personality didn’t help. He felt out of place in Huntsville and in the United States and harbored resentment for some of his former colleagues, who he believed had betrayed him.

The Army also had reasons to avoid bringing attention to the mentor of the world’s most famous rocket designer. Oberth was notorious for making provocative or controversial remarks. He might, for instance, insist with icy certitude that at age sixty-four he should be chosen as an astronaut. “They should send old men as explorers. We’re expendable.” Or he might try to argue why Hitler “wasn’t all that bad” or explain how if Germany had won the war Hitler would have funded space travel more vigorously than either the Soviets or the Americans.

And then there were the UFOs. By the mid-1950s Oberth had announced that the rash of UFO sightings indicated that Earth was being visited by extraterrestrials. He appeared at UFO conferences and expounded with deadly seriousness about the lost continent of Atlantis and its connection to Germany.

So when he reached the mandatory retirement age of sixty-five, few in Huntsville objected to his decision to collect his pension back in Germany. Oberth announced he would devote his time to philosophy. “Our rocketry is good enough, our philosophy is not.”

VON BRAUN’S TRIUMPH with Explorer did little to rectify the ongoing competition among the different branches of the armed forces. Former defense secretary Wilson’s decision two years earlier to give the Air Force responsibility for long-range ballistic missiles implied it would become the branch designated to oversee any future military activities in earth orbit. However, von Braun and General Medaris at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency continued to work on their own ambitious ideas, including plans for a large heavy-lifting rocket that could place human-piloted vehicles in orbit.

The ongoing competition extended into the services’ public marketing campaigns, with the Army, Air Force, and Navy each promoting their leadership in the dawning space age. The Navy regarded space as a new ocean to conquer and command, in keeping with von Braun’s allusion to the great maritime powers of the past. The Air Force argued that space was an extension of the conquest of the air, just at a higher altitude, and coined its own marketing term, “aerospace.” And the Army, while regarding rocketry as a high-powered extension of the artillery, also used the launch of Explorer to promote itself as the team that got things done.

Shortly after Sputnik and the panic on Capitol Hill, the Air Force inaugurated its own piloted spacecraft program, called Man in Space Soonest. Its Special Weapons Center even commissioned a top-secret fast-track study, code named Project A119, to evaluate the scientific paybacks of Fred Singer’s proposal to explode thermonuclear weapons on the Moon, an idea some in the Air Force believed would demonstrate to the world America’s military prowess and instill patriotic pride at home.

© Recruiting posters (Public Domain, private collections)

By the late 1950s, the Army, Navy, and Air Force were each employing space age–themed marketing campaigns to encourage new recruits. The Army’s poster celebrates the launch of Explorer I, the Navy’s includes a picture of Vanguard, and the Air Force promotes its plans for a human military presence in outer space.

President Eisenhower realized he needed to resolve the ongoing service rivalry that was becoming counterproductive and costly to the country. He was also increasingly wary of the power of some personalities in the American military to influence public opinion and gain congressional backing for their ambitious and expensive projects. Accordingly, Eisenhower decided to reduce the military’s role in future human spaceflight by signing into law the National Aeronautics and Space Act. His announcement in late July 1958 followed a Presidential Science Advisory Committee that recommended developing space technology in response to the “compelling urge of man to explore and to discover, the thrust of curiosity that leads men to try to go where no one has gone before.” It was a declaration that—when slightly reworked with the adverb “boldly” in the prelude to the television series Star Trek eight years later—would become one of the most familiar catchphrases of the latter half of the twentieth century. Presciently sensing the emotions those words would invoke, Eisenhower noted in an accompanying letter, “This is not science fiction … every person has the opportunity to share through understanding in the adventures which lie ahead.”

The National Aeronautics and Space Act created a new civilian space agency, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), built in part from the half-century-old National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), which was already dedicating half its resources to space-related projects, including Vanguard and the X-15 suborbital space plane. Chosen as NASA’s first administrator was the president of Case Institute of Technology, T. Keith Glennan, a former member of the Atomic Energy Commission.

Within the first week of NASA’s creation, the Air Force terminated its nascent Man in Space Soonest initiative. NASA would now oversee a new civilian-run program, named Project Mercury, dedicated to putting the first Americans into space. Instead, the Air Force would concentrate on its own piloted winged space glider, known as Dyna-Soar, which, after being launched on top of a ballistic missile, would allow military crews to service satellites, conduct aerial reconnaissance, and possibly intercept enemy satellites.

Despite the idealistic rhetoric about exploration and adventure, it was impossible to conceal the reality that the civilian agency planned to send Americans into space atop repurposed military missiles developed to deliver warheads and transport reconnaissance spy satellites. The United States therefore chose to emphasize the open, peaceful, and cooperative nature of its civilian space program, which stood in contrast with the secretive and militarily aligned Soviet effort.

Remarkably, the Soviet Union had never placed a high priority on launching the world’s first artificial satellite. Rather, its military rocket program had been developed to inform the world that Russia had the capability to strike other nations with nuclear weapons. Sputnik was an unexpected dividend after von Braun’s Soviet counterpart, Sergei Korolev, developed a heavy-lifting rocket—the R-7—capable of delivering a six-ton nuclear warhead. But the Soviet warhead turned out to be far lighter than the original estimate; Korolev had designed a rocket much more powerful than needed.

Korolev realized the R-7 could put a satellite in orbit, if that was of interest to the Kremlin. Following Eisenhower’s International Geophysical Year announcement, Korolev sent a memo noting that should Russia want to set a world record by launching a satellite, they could do so at practically no additional cost. When Khrushchev gave his consent, he never anticipated the alarmist reaction in the United States. While the Soviet space program’s principal purpose was—and remained—military, Sputnik’s overnight success suddenly elevated the role of space research in the eyes of the Kremlin, making it an engineering, scientific, and propaganda priority.

NASA’s charter specifically restricted it from any responsibility for military defensive weapons or reconnaissance satellites. That separation between NASA and the Pentagon allowed it to act as Washington’s public face for promoting scientific research, furthering exploration, and bolstering national prestige, while deflecting attention from ongoing military space initiatives. In fact, during NASA’s first year of operation, the Pentagon’s space budget was nearly 25 percent larger.