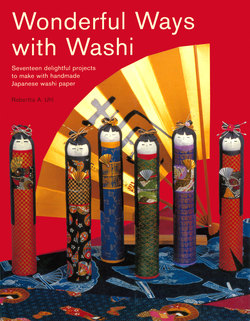

Читать книгу Wonderful Ways with Washi - Robertta A. Uhl - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Washi, literally "traditional Japanese paper", is the Japanese word for all types of paper, including traditional handmade sheets as well as similar-looking papers produced by modern manufacturing methods. This book, however, is concerned with the paper made by hand by artisans all over Japan.

Washi paper is the material of the craftsman, the painter, the calligrapher, the designer, the architect, and the tea master. Paper screens are an integral part of every house. People in both town and country use Japanese paper in all aspects of their daily lives: in umbrellas, fans, lanterns, lamps, containers, toys, origami, and other crafts. In Shinto rites, paper symbolizes the purifying aspect of the god.

Although the art of making paper was first developed in China, it spread to Japan in the seventh century AD along with Buddhism. Buddhist monks initially produced it for writing scriptures, but the flowering of a court culture during the Heian period (794—1192) created a demand for official papers and for decorated sheets for poetry and diaries. This, in turn, stimulated the development of government mills as well as a local cottage industry. The decline of the imperial court and the rise of the samurai warrior class after AD 1192, led to a demand for good-quality utility paper, while the development of printing and the architectural use of paper in sliding screens and doors added a new dimension to paper consumption. By the late 1800s, more than 100,000 Japanese families were making paper by hand for everyday use—for utensils, housing, and even clothing. After the opening of Japan to the West during the Meiji Restoration, mechanized paper-making technology was introduced to Japan, creating stiff competition for local paper-making households. However, a vigorous folk craft market from the mid-1920s, as well as a publishing boom after World War II, stimulated a demand for large quantities of handmade paper. Although only 350 families were still actively producing Washi in the mid-1990s, the unbelievable range of color, textures, and designs of the papers which continue to be produced, is testimony to Japan's unrivalled skill in all types of paper making. Japan continues to produce a greater quantity and variety and a higher quality of handmade paper than the rest of the world combined.

Washi is traditionally made by hand from the long inner fibers of the bark of three native plants: the kozo, mitsumata, and gampi. Kozo (Broussonetia kazinoki) is a shrub of the mulberry family. Reaching 3 meters at full growth, the plant is easy to cultivate and regenerates annually. The inner bast fiber is the longest, thickest and strongest of the three plants and is therefore the most widely used in paper-making; kozo is also considered the masculine element, the protector. Mitsumata (Edgeworthia chrysantha), a shrub of the daphne family, reaches a height of 2 meters. Graceful, delicate and soft—it is said to be the feminine element—it can be harvested only once every three years after planting and its paper is therefore more expensive. Because its fiber is thin and soft, it produces smooth paper with excellent printability. It is also insect resistant. Gampi (Wikstroemia sikokiana), like mitsumata, is a shrub of the daphne family, reaching a height of 2 meters when mature. The earliest fiber to be used for paper making, and considered to be the noblest because of its richness, dignity and longevity, the long, thin fibers produce the most lustrous of the three papers. However, the relative scarcity of the plant make its papers the most expensive. Other natural fibers, such as abaca, hemp, horsehair and rayon, as well as silver and gold foil, are sometimes used for making Washi or are mixed in with the other fibers for decorative effect.

The leaves and roots of a mulberry plant.

Pulverized mulberry roots being pressed into sheets in a boxed frame.

Sheets of paper put out to dry on boards before designs are stenciled on them.

To make Washi from the kozo mulberry, the plant is cut down to the root when mature, then cut in two. The top half is debarked and used as firewood. The bottom half is also debarked, then boiled until it turns black, and hung out to dry. The branches are then rinsed and stomped on by foot until they are soft and the fibers separate to form a pulp. The rough edges are stripped off before the fibers are once again rinsed and hung out to dry. They are then boiled again, this time with the ashes from the top part of the plant that was previously used as firewood. This mixture is then pulverized and a paste from the root of a plant called taroimo, which comes from the potato family, is added to the mixture. The wet mixture is then stacked together and gently pressed on to a boxed frame into sheets, causing the bark to become fibrous and interwoven. After the mixture has settled, the sheets are carefully separated and pulled out of the press, one at a time. Each sheet is brushed on to a framed board and set outside to dry. When the sheets are completely dry, they are ready to have the printed design stenciled on, a process similar to silk screening. One color is applied at a time until the desired design is completed. The finished Washi is then called Yuzen ("hand-printed patterned paper").

Since the long plant fibers that compose the paper are of uniform length (about ¼") and become thoroughly intertwined during the paper-making process, Washi is very tough, flexible and durable; it does not tear like regular paper when dampened with paste and is said to last up to 1,000 years! Yet, it has a very soft texture and appearance, and because of its non-acidic components is extremely light. The thickness of Washi varies from lacy tissue to card stock. Its texture may be smooth, rough or crinkled. Because of the papers natural qualities, it is not surprising that Washi is the favorite and most commonly used craft paper among the Japanese.

More recently, Westerners have begun to explore the possibilities of using this beautiful paper in their crafts. They are attracted to the colors, textures and weights of the paper, and also to the delightful designs, many of which capture the spirit of Japans great textile tradition. Washi patterns range from classic motifs depicting Japan's rich cultural heritage (kimonos, fans, Kabuki actors) to motifs inspired by nature (bamboo, flowers, cranes). Not only are the motifs noteworthy for their elegance, delicacy, refinement, rich colors and attention to detail, but they are also executed with a wonderful sense of the abstract.

Westerners, like myself, who live in Japan, have discovered many enjoyable ways to use printed Washi. In this book, Wonderful Ways With Washi, I have included some of the most popular Washi projects that I teach. They are all elegant, creative, simple yet challenging, and the finished products are strikingly beautiful in any setting. These simple-to-make, hand-crafted projects, suitable for all occasions are presented in a series of easy-to-follow, step-by-step instructions. Each step is illustrated, for additional guidance. It is my hope that this book will help you to discover the wonderful Washi crafts that offer a delightful alternative to store-bought gifts—a wonderful way to leave a warm and lasting impression.