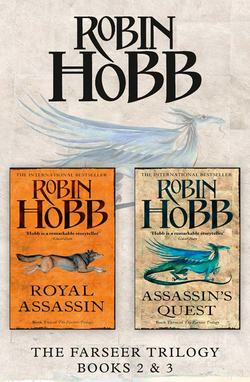

Читать книгу The Farseer Series Books 2 and 3: Royal Assassin, Assassin’s Quest - Робин Хобб - Страница 20

TEN Fool’s Errand

ОглавлениеIn times of peace, the teaching of the Skill was restricted to those of royal blood, to keep the magic more exclusive and reduce the chance of it being turned against the King. Thus, when Galen became apprentice to Skillmaster Solicity, his duties consisted of assisting in completing the training of Chivalry and Verity. No others were receiving instruction at that time. Regal, a delicate child, was judged by his mother to be too sickly to withstand the rigours of the Skill training. Thus, after Solicity’s untimely death, Galen came to the title of Skillmaster, but had few duties. Some, at least, felt that the time he had served as apprentice to Solicity was insufficient to be the full training of a Skillmaster. Others have averred that he never possessed the Skill strength necessary to be a true Skillmaster. In any case, during those years he had no opportunity to prove himself, and disprove his critics. There were no young princes or princesses to train during the years that Galen was Skillmaster.

It was only with the Red Ship raids that it was decided that the circle of those trained in the Skill must be expanded. A proper coterie had not existed for years. Tradition tells us that in previous troubles with the Outislanders, it was not unusual for three, or even four coteries to exist. These usually consisted of six to eight members, mutually chosen, well suited to be bonded among themselves, and with at least one member possessing a strong affinity with the reigning monarch. This key member reported directly to the monarch all that his coterie members relayed to him, if they were a messaging, or information-gathering coterie. Other coteries existed to pool strength and extend to the monarch their Skilling resources as he might need them. The key members in these coteries were often referred to as a King’s or Queen’s Man or Woman. Very rarely, such a one existed independent of any coterie or training, but simply as one who had such an affinity for the monarch that strength could be tapped, usually by a physical touch. From this key member, the monarch could draw endurance as needed to sustain a Skilling effort. By custom, a coterie was named after its key member. Thus we have legendary examples such as Crossfire’s Coterie.

Galen chose to ignore all tradition in the creation of his first and only coterie. Galen’s Coterie came to be named after the Skillmaster who fashioned it, and retained that name even after his death. Rather than creating a pool of Skilled ones and letting a coterie emerge from it, Galen himself selected those who would be members of it. The coterie lacked the internal bonding of the legendary groups, and their truest affinity was to the Skillmaster rather than to the King. Thus, the key member, initially August, reported to Galen fully as often as he reported to King Shrewd or King-in-Waiting Verity. With the death of Galen and the blasting of August’s Skill sense, Serene rose to be key member of Galen’s Coterie. The other surviving members of the group were Justin, Will, Carrod and Burl.

By night I ran as a wolf.

The first time I thought it a singularly vivid dream. The wide stretch of white snow with the inky tree shadows spilled on it, the elusive scents on the cold wind, the ridiculous fun of bounding and digging after shrews that ventured out of their winter burrows. I awoke clear-minded and good-tempered.

But the next night I dreamed again as vividly. I awoke knowing that when I blocked from Verity and hence myself my dreams of Molly, I left myself wide to the wolf’s night thoughts. Here was a whole realm where neither Verity nor any Skilled one could follow me. It was a world bereft of court intrigues or plotting, of worries and plans. My wolf lived in the present. I found his mind clean of the cluttering detail of memories. From day to day, he carried only that necessary to his survival. He did not remember how many shrews he had killed two nights ago, but only larger things, such as which game yielded the most rabbits to chase or where the spring ran swift enough that it never iced over.

This, then, was when and how I first showed him how to hunt. We did not do so well at first. I still arose very early each morning, to take him food as needed. I told myself that it was but a small corner of my life that I kept for myself. It was as the wolf had said, not a thing I did, but something I was. Besides, I promised myself, I would not let this joining become a full bond. Soon, very soon, he would be able to hunt for himself, and I would send him away to be free. Sometimes I told myself that I permitted him into my dreams only that I might teach him to hunt, the sooner to set him free. I refused to consider what Burrich would think of such a thing.

I returned from one of my early morning expeditions to find two soldiers sparring with one another in the kitchen yard. They had staves and were good-naturedly insulting one another as they huffed and shifted and traded whacks in the cold clear air. The man I did not know at all, and for a moment I thought both were strangers. Then the woman of the pair caught sight of me. ‘Ho! FitzChivalry. A word with you!’ she called, but without retiring her stave.

I stared at her, trying to place her. Her opponent missed a parry and she clipped him sharply with her stave. As he hopped, she danced back and laughed aloud, an unmistakable high-pitched whinny. ‘Whistle?’ I asked incredulously.

The woman I had just addressed flashed her famous gap-toothed smile, caught her partner’s stave a ringing blow and danced back again. ‘Yes?’ she asked breathlessly. Her sparring partner, seeing her occupied, courteously lowered his stave. Whistle immediately darted hers at him. With so much skill he almost looked lazy, his stave leaped up to counter hers. Again she laughed and held up her hand to ask a truce.

‘Yes,’ she repeated, this time turning to me. ‘I’ve come … that is, I’ve been chosen to come and ask a favour of you.’

I gestured at the clothes she wore. ‘I don’t understand. You’ve left Verity’s guard?’

She gave a tiny shrug, but I could see the question delighted her. ‘But not to go far. Queen’s Guard. Vixen badge. See?’ She tugged the front of the short white jacket she wore to hold the fabric taut. Good sensible woollen homespun, I saw, and saw too the embroidered snarling white fox on a purple background. The purple matched the purple of her heavy woollen trousers. The loose cuff had been tucked into knee-boots. Her partner’s garb matched hers. Queen’s Guard. In light of Kettricken’s adventure, the uniform made sense.

‘Verity decided she needed a guard of her own?’ I asked delightedly.

The smile faded a bit from Whistle’s face. ‘Not exactly,’ she hedged, and then straightened as if reporting to me. ‘We decided she needed a Queen’s Guard. Me and some of the others that rode with her the other day. We got to talking about … everything, later. About how she handled herself out there. And back here. And how she came here, all alone. We talked about it then, that someone should get permission to form up a guard for her. But none of us really knew how to approach it. We knew it was needed, but no one else seemed to be paying much attention … but then last week, at the gate, I heard you got pretty hot about how she’d gone out, on foot and alone, and no one at her back. Well you did! I was in the other room, and I heard!’

I bit back my protest, nodded curtly, and Whistle went on. ‘So. Well, we just did. Those of us who felt we wanted to wear the purple and white just said so. It was a pretty even split. It was time to take in some new blood anyway; most of Verity’s guard was getting a bit long in the tooth. And soft, from too much time in the keep. So we reformed, giving rank to some who should have made it long ago, if there’d been any openings to fill, and taking in some recruits to fill in where needed. It all worked out perfectly. These newcomers will give us something to hone our skills on while we teach them. The Queen will have her own guard, when she wants one. Or needs one.’

‘I see.’ I was beginning to get an uneasy feeling. ‘And what was the favour you wanted of me?’

‘Explain it to Verity. Tell the Queen she has a guard.’ She said the words simply and quietly.

‘This walks close to disloyalty,’ I said just as simply. ‘Soldiers of Verity’s own guard, setting aside his colours to take on his queen’s …’

‘Some might see it that way. Some might speak it that way.’ Her eyes met mine squarely, and the smile was gone from her face. ‘But you know it is not. It’s a needed thing. Your … Chivalry would have seen it, would have had a guard for her before she even arrived here. But King-in-Waiting Verity … well, this is no disloyalty to him. We’ve served him well, because we love him. Still do. This is those who’ve always watched his back, falling back and reforming to watch his back even better. That’s all. He’s got a good queen, is what we think. We don’t want to see him lose her. That was all. We don’t think any the less of our King-in-Waiting. You know that.’

I did. But still. I looked away from her plea, shook my head and tried to think. Why me? a part of me demanded angrily. Then I knew, that in the moment I’d lost my temper and berated the guard for not protecting their queen, I’d volunteered for this. Burrich had warned me about not remembering my place. ‘I will speak to King-in-Waiting Verity. And to the Queen, if he approves this.’

Whistle flashed her smile again. ‘We knew you’d do it for us. Thanks, Fitz.’

As quickly she was spinning away from me, stave at the ready as she danced threateningly toward her partner, who gave ground grudgingly. With a sigh, I turned away from the courtyard. I had thought Molly would be fetching water at this time. I’d hoped for a glimpse of her. But she was not, and I left feeling disappointed. I knew I should not play at such games, but some days I could not resist the temptation. I left the courtyard.

The last few days had become a special sort of self-torture for me. I refused to allow myself to see Molly again, but could not resist shadowing her. So I was in the kitchen but a moment after she had left, fancying I could still catch the trace of her perfume in the air. Or I stationed myself in the Great Hall of an evening, and tried to be where I could watch her without being noticed. No matter what amusement was offered, minstrel or poet or puppeteer, or just folk talking and working on their handicrafts, my eyes would be drawn always to wherever Molly might be. She looked so sober and demure in her dark blue skirts and blouse, and she had never a glance for me. Always she spoke with the other keep women, or on the rare evenings when Patience chose to descend, she sat beside her and attended to her with a focus of attention that denied I even existed. Sometimes I thought my brief encounter with her had been a dream. But at night I could go back to my room, and take out the shirt I had hidden in the bottom of my clothes chest, and if I held it close to my face, I fancied I could still smell the faint trace of her perfume upon it. And so I endured.

A number of days had passed since we had burned the Forged ones on their funeral pyre. In addition to the formation of the Queen’s Guard, other changes were afoot within and without the keep. Two other master boat-builders, unsummoned, had come to volunteer their skills for the building of the ships. Verity had been delighted. But even more so had Queen Kettricken been moved, for it was to her that they presented themselves, saying that they desired to be of service. Their apprentices came with them, to swell the ranks of those working in the shipyards. Now the lamps burned both before dawn and after the sun’s setting, and work proceeded at a breakneck pace. So Verity was away all the more, and Kettricken, when I called on her, was more subdued than ever. I tempted her with books or outings to no avail. She spent most of her time sitting near idle at her loom, growing more pale and listless with every passing day. Her dark mood infected those ladies who attended her, so that to visit her room was as cheery as keeping a death watch.

I had not expected to find Verity in his study, and was not disappointed. He was down at the boat-sheds, as always. I left word with Charim to ask that I be summoned whenever Verity might have the time to see me. Then, with a resolve to keep myself busy and to do as Chade suggested, I returned to my room. I took both dice and tally sticks with me, and headed for the Queen’s chambers.

I had resolved to teach her some of the games of chance that the lords and ladies were fond of, in the hopes that she might expand her circle of entertainments. I also hoped, with less expectation, that such games might draw her to socialize more widely and to depend less on my companionship. Her bleak mood was beginning to burden me with its oppressiveness, so that I often heartily wished to be away from her.

‘Teach her to cheat first. Only, just tell her that’s how the game is played. Tell her the rules permit deception. A bit of sleight of hand, easily taught, and she could clean Regal’s pockets for him a time or two before he dared suspect her. And then what could he do? Accuse Buckkeep’s lady of cheating at dice?’

The Fool, of course. At my elbow, companionably pacing alongside me, his rat sceptre jouncing lightly on his shoulder. I did not startle physically, but he knew that, once more, he had taken me by surprise. His amusement shone in his eyes.

‘I think our Queen-in-Waiting might take it amiss if I so misinformed her. Why do you not come with me instead, to brighten her spirits a bit? I shall set aside the dice, and you can juggle for her,’ I suggested.

‘Juggle for her? Why, Fitz, that is all I do, all day long, and you see it as but my foolery. You see my work and deem it play, while I see you work so earnestly at playing games you have not yourself devised. Take a Fool’s advice on this. Teach the lady not dice, but riddles, and you will both be the wiser.’

‘Riddles? That’s a Bingtown game, is it not?’

‘’Twere one played well at Buckkeep these days. Answer me this one, if you can. How does one call a thing when one does not know how to call it?’

‘I have never been any good at this game, Fool.’

‘Nor any other of your blood-line, from what I have heard. So answer this. What has wings in Shrewd’s scroll, a tongue of flame in Verity’s book, silver eyes in the Relltown Vellums, and gold-scaled skin in your room?’

‘That’s a riddle?’

He looked at me pityingly. ‘No. A riddle is what I just asked you. That’s an Elderling. And the first riddle was, how do you summon one?’

My stride slowed. I looked at him more directly, but his eyes were always difficult to meet. ‘A riddle, or a serious question?’

‘Is that a riddle? Or a serious question?’

‘Yes.’ The Fool was grave.

I stopped in mid-stride, completely bemuddled. I glared at him. In answer, he went nose to nose with his rat sceptre. They simpered at one another. ‘You see, Ratsy, he knows no more than his uncle or his grandfather. None of them knows how to summon an Elderling.’

‘By the Skill,’ I said impetuously.

The Fool looked at me strangely. ‘You know this?’

‘I suspect it is so.’

‘Why?’

‘I don’t know. Now that I consider it, I do not think it likely. King Wisdom made a long journey to find the Elderlings. If he could simply have Skilled to them, why didn’t he?’

‘Indeed. But sometimes there is truth in impetuosity. So riddle me this, boy. A king is alive. Likewise a prince. And both are Skilled. But where are those who trained alongside the King, or those who trained before him? How come we to this, this paucity of Skilled ones at a time when they are so grievously needed?’

‘Few are trained in times of peace. Galen didn’t see fit to train any, up until his last year. And the coterie he created …’ I paused suddenly, and though the corridor was empty, I suddenly did not want to speak any more about it. I had always kept whatever Verity told me about the Skill in confidence.

The Fool pranced in a sudden circle about me. ‘If the shoe does not fit, one cannot wear it, no matter who made it for you,’ he declared.

I nodded grudgingly. ‘Exactly.’

‘And he who made it is gone. Sad. So sad. Sadder than hot meat on the table and red wine in your glass. But he who is gone was made by someone in turn.’

‘Solicity. But she is also gone.’

‘Ah. But Shrewd is not. Nor Verity. It seems to me, that if there are two she created still breathing, there ought to be others. Where are they?’

I shrugged. ‘Gone. Old. Dead. I don’t know.’ I forced my impatience down, tried to consider his question. ‘King Shrewd’s sister, Merry. August’s mother. She would have been trained, perhaps, but she is long dead. Shrewd’s father, King Bounty was the last to have a coterie, I believe. But very few folk of that generation are still alive.’ I halted my tongue. Verity had once told me that Solicity had trained as many in the Skill as she could find the talent in. Surely there must be some of them left alive; they would be no more than a decade or so older than Verity …

‘Dead, too many of them, if you ask me. I do know.’ The Fool interjected an answer to my unspoken question. I looked at him blankly. He stuck his tongue out at me, waltzed away from me a bit. He considered his sceptre, chucked the rat lovingly under the chin. ‘You see, Ratsy, it is as I told you. None of them know. None of them are smart enough to ask.’

‘Fool, cannot you ever speak plain?’ I cried out in frustration.

He halted as suddenly as if struck. In mid-pirouette, he lowered his heels to the floor and stood like a statue. ‘Would it help at all?’ he asked soberly. ‘Would you listen to me if I came to you and did not speak in riddles? Would that make you pause and think and hang upon every word, and ponder those words later, in your chamber? Very well then. I shall try. Do you know the rhyme, Six Wisemen went to Jhaampe-town?’

I nodded, as confused as ever.

‘Recite it for me.’

‘Six Wisemen went to Jhaampe-town, climbed a hill and never came down, turned to stone and flew away…’ The old nursery rhyme eluded me suddenly. ‘I don’t recall it at all. It’s nonsense anyway, one of those rhyming things that sticks in your head but means nothing.’

‘That, of course, is why it is enscrolled with the knowledge verses,’ the Fool concluded.

‘I don’t know!’ I retorted. I suddenly felt irritated beyond endurance. ‘Fool, you are doing it again. All you speak is riddles, ever! You claim to speak plain, but your truth eludes me.’

‘Riddles, dear Fitzy-fitz, are supposed to make folk think. To find new truth in old saws. But, be that as it may … Your brain eludes me. How shall I reach it? Perhaps if I came to you, by dark of night, and sang under your window:

Bastard princeling, Fitz my sweet,

You waste your hours to your own defeat.

You work to stop, you strive to refrain,

When all your effort should go to a gain.’

He had flung himself to one knee, and plucked nonexistent strings on his sceptre. He sang quite lustily, and even well. The tune belonged to a popular love ballad. He looked at me, sighed theatrically, wet his lips and continued mournfully,

‘Why does a Farseer look never afar,

Why dwells he completely in things as they are?

Your coasts are besieged, your people beset.

I warn and I urge, but they all say, “not yet!”

Oh bastard princeling, gentle Fitz,

Will you delay until chopped to bits?’

A passing servant girl paused to stand bemused and listen. A page came to the door of one chamber and peeped out at us, grinning widely. A slow flush began to heat my cheeks, for the Fool’s expression was both tender and ardent as he looked up at me. I tried to walk casually away from him, but he followed me on his knees, clutching at my sleeve. I was forced to stand, or engage in a ridiculous struggle to free myself. I stood, feeling foolish. He simpered a smile up at me. The page giggled, and down the hall I heard two voices conferring in amusement. I refused to lift my eyes to see who was so enjoying my discomfort. The Fool mouthed a kiss up at me. He let his voice sink to a confidential whisper as he sang on:

‘Will fate seduce you to her will?

Not if you struggle with all your Skill.

Summon your allies, locate the trained,

Consummate all from which you’ve refrained.

There’s a future not yet fashioned

Founded by your fiery passions.

If you use your Wits to win

You’ll save the duchies for your kin.

Thus begs a Fool, on bended knee,

Let not a darkness come to be.

Let not our peoples go to dust

When Life in you has placed this trust.’

He paused, then sang loudly and jovially:

‘And if you choose to let this pass

Like so much farting from your ass,

Behold my reverence for thee,

Feast eyes on what men seldom see!’

He suddenly released my cuff, to tumble away from me in a somersault that somehow reached a finish with his presentation of his bare buttocks to me. They were shockingly pale, and I could conceal neither my amazement nor affront. The Fool vaulted to his feet, suitably clothed again, and Ratsy on his sceptre bowed most humbly to all who had paused to watch my humiliation. There was general laughter and a scattering of applause. His performance had left me speechless. I looked aside and tried to walk past him, but with a bound the Fool blocked my passage once again. The Fool abruptly assumed a stern stance and addressed all who still grinned.

‘Fie and shame upon you all, to be so merry! To giggle and point at a boy’s broken heart! Do not you know the Fitz has lost one most dear to him? Ah, he hides his grief beneath his blushes, but she has gone to her grave and left his passion unslaked. That most stubbornly chaste and virulently flatulent of maidens, dear Lady Thyme, has perished. Of her own stench, I doubt it not, though some say it came of eating spoiled meat. But spoiled meat, you say, has a most foul odour, to warn off any from consuming it. Such we can say of Lady Thyme also, and so perhaps she smelt it not, or deemed it but the perfume of her fingers. Mourn not, poor Fitz, another shall be found for you. To this I shall devote myself, this very day! I swear it, by Sir Ratsy’s skull. And now, I bid you hasten on your tasks, for in truth I have delayed mine much too long. Fare well, poor Fitz. Brave, sad heart! To put so bold a face on your desolation! Poor disconsolate youth! Ah, Fitz, poor poor Fitz …’

And he wandered off down the hall from me, shaking his head woefully, and conferring with Ratsy as to which elderly dowager he should court on my behalf. I stared in disbelief after him. I felt betrayed, that he could make so public a spectacle of me. Sharp-tongued and flighty as the Fool could be, I had never expected to be the public butt of one of his jokes. I kept waiting for him to turn around, and say some last thing that would make me understand what had just happened. He did not. When he turned a corner, I perceived that my ordeal was finally at an end. I proceeded down the hallway, fuming with embarrassment and dazed with puzzlement at the same time. The doggerel of his rhymes had stored his words in my head, and I knew that I would ponder his love song much in days to come, to try and worry out the meanings hidden there. But Lady Thyme? Surely he would not say such a thing, were it not ‘true’. But why would Chade allow his public personage to die in such a way? What poor woman’s body would be carried out as Lady Thyme, no doubt to be carted off to distant relatives for burial? Was this his method of beginning his journey, a way to leave the keep unseen? But again, why let her be dead? So that Regal might believe he had succeeded in his poisoning? To what end?

Thus bemused, I finally came to the doors of Kettricken’s chamber. I stood in the hall a moment, to recover my aplomb and compose my face. Suddenly the door across the hall flung open and Regal strode into me. His momentum jostled me aside, and before I could recover myself, he grandly offered, ‘It’s all right, Fitz. I scarcely expect an apology from one so bereaved as yourself.’ He stood in the hallway, straightening his jerkin as the young men following him emerged from his chamber, tittering in amusement. He smiled round at them, and then leaned close to me to ask, in a quietly venomous voice, ‘Where will you suckle up now that the old whore Thyme is dead? Ah, well. I am sure you will find some other old woman to coddle you. Or are you come to wheedle up to a younger one, now?’ He dared to smile at me, before he spun on his heel and strode off in a fine flutter of sleeves, trailed by his three sycophants.

The insult to the Queen poisoned me into rage. It came with a suddenness such as I had never experienced. I felt my chest and throat swell with it. A terrible strength rushed through me; I know my upper lip lifted in a snarl. From afar I sensed, What? What is it? Kill it! Kill it! Kill it! I took a step, the next would have been a spring, and I know my teeth would have sunk into the place where throat meets shoulder.

But, ‘FitzChivalry,’ said a voice, full of surprise.

Molly’s voice! I turned to her, my emotions wrenching from rage to delight at seeing her. But as swiftly she was turning aside, saying, ‘Beg pardon, my lord,’ and brushing past me. Her eyes were down, her manner that of a servant.

‘Molly?’ I called, stepping after her. She paused. When she looked back at me, her face was empty of emotion, her voice neutral.

‘Sir? Had you an errand for me?

‘An errand?’ Of course. I glanced about us, but the corridor was empty. I took a step toward her, pitched my voice low for her ears only. ‘No. I’ve just missed you so, Molly, I…’

‘This is not seemly, sir. I beg you to excuse me.’ She turned, proudly, calmly, and walked away from me.

‘What did I do?’ I demanded, in angry consternation. I did not really expect an answer. But she paused. Her blue-clothed back was straight, her head erect under her tatted hair-cloth. She did not turn back to me, but said quietly, to the corridor. ‘Nothing. You did nothing at all, my lord. Absolutely nothing.’

‘Molly!’ I protested, but she turned the corner and was gone. I stood staring after her. After a moment, I realized I was making a sound somewhere between a whine and a growl.

Let us go hunting instead.

Perhaps, I found myself agreeing. That would be the best thing. To go hunting, to kill, to eat, to sleep. And to do no more than that.

Why not now?

I don’t really know.

I composed myself and knocked at Kettricken’s door. It was opened by little Rosemary who dimpled a smile at me as she invited me in. Once within, Molly’s errand here was evident. Kettricken was holding a fat green candle under her nose. On the table were several others. ‘Bayberry,’ I observed.

Kettricken looked up with a smile. ‘FitzChivalry. Welcome. Come in and be seated. May I offer you food? Wine?’

I stood looking at her. A sea change. I felt her strength, knew she stood in the centre of herself. She was dressed in a soft grey tunic and leggings. Her hair was dressed in her customary way. Her jewellery was simple, a single necklace of green and blue stone beads. But this was not the woman I had brought back to the keep a few days ago. That woman had been distressed, angry, hurt and confused. This Kettricken welled serenity.

‘My queen,’ I began, hesitantly.

‘Kettricken,’ she corrected me calmly. She moved about the room, setting some of the candles on shelves. It was almost a challenge in that she did not say more.

I came further into her sitting room. She and Rosemary were the only occupants. Verity had once complained to me that her chambers had the precision of a military encampment. It had not been an exaggeration. The simple furnishings were spotlessly clean. The heavy tapestries and rugs that furnished most of Buckkeep were missing here. Simple mats of straw were on the floor, and frames supported parchment screens painted with delicate sprays of flowers and trees. There was no clutter at all. In this room, all was finished and put away, or not yet begun. That is the only way I can describe the stillness I felt there.

I had come in a roil of conflicting emotions. Now I stood still and silent, my breathing steadying and my heart calming. One corner of the chamber had been turned into an alcove walled with the parchment screens. Here there was a rug of green wool on the floor, and low padded benches such as I had seen in the mountains. Kettricken placed the green bayberry candle behind one of the screens. She kindled it with a flame from the hearth. The dancing candlelight behind the screen gave the life and warmth of a sunrise to the painted scene. Kettricken walked around to sit on one of the low benches within the alcove. She indicated the bench opposite hers. ‘Will you join me?’

I did. The gently-lit screen, the illusion of a small private room and the sweet scent of bayberry surrounded me. The low bench was oddly comfortable. It took me a moment to recall the purpose of my visit. ‘My queen, I thought you might like to learn some of the games of chance we play at Buckkeep. So you could join in when the other folk are amusing themselves.’

‘Perhaps another time,’ she said kindly. ‘If you and I wish to amuse ourselves, and if it would please you to teach me the game. But for those reasons only. I have found the old adages to be true. One can only walk so far from one’s true self before the bond either snaps, or pulls one back. I am fortunate. I have been pulled back. I walk once more in trueness to myself, FitzChivalry. That is what you sense today.’

‘I don’t understand.’

She smiled. ‘You don’t need to.’

She fell silent again. Little Rosemary had gone to sit by the hearth. She took up her slate and chalk as if to amuse herself. Even that child’s normal merriment seemed placid today. I turned back to Kettricken and waited. But she only sat looking at me, a bemused smile on her face.

After a moment or two, I asked, ‘What are we doing?

‘Nothing,’ Kettricken said.

I copied her silence. After a long time, she observed, ‘Our own ambitions and tasks that we set for ourselves, the framework we attempt to impose upon the world is no more than a shadow of a tree cast across the snow. It will change as the sun moves, be swallowed in the night, sway with the wind and when the smooth snow vanishes, it will lie distorted upon the uneven earth. But the tree continues to be. Do you understand that?’ She leaned forward slightly to look into my face. Her eyes were kind.

‘I think so,’ I said uneasily.

She gave me a look almost of pity. ‘You would if you stopped trying to understand it, if you gave up worrying about why this is important to me, and simply tried to see if it is an idea that has worth in your own life. But I do not bid you to do that. I bid no one do anything here.’

She sat back again, a gentle loosening that made her straight spine seem effortless and restful. Again, she did nothing. She simply sat across from me and unfurled herself. I felt her life brush up against me and flow around me. It was but the faintest touching, and had I not experienced both the Skill and the Wit, I do not think I would have sensed it. Cautiously, as softly as if I assayed a bridge made of cobweb, I overlay my senses on hers.

She quested. Not as I did, toward a specific beast, or to read what might be close by. I discarded the word I had always given to my sensing. Kettricken did not seek after anything with her Wit. It was as she said, simply a being, but it was being a part of the whole. She composed herself and considered all the ways the great web touched her, and was content. It was a delicate and tenuous thing and I marvelled at it. For an instant I too relaxed. I breathed out. I opened myself, Wit wide to all. I discarded all caution, all worry that Burrich would sense me. I had never done anything to compare it to before. Kettricken’s reaching was as delicate as droplets of dew sliding down a strand of spider web. I was like a dammed flood, suddenly released, to rush out to fill old channels to overflowing and to send fingers of water investigating the lowlands.

Let us hunt! The wolf, joyfully.

In the stables, Burrich straightened from cleaning a hoof, to frown at no one. Sooty stamped in her stall. Molly shrugged away and shook out her hair. Across from me, Kettricken started and looked at me as if I had spoken aloud. A moment more I was held, seized from a thousand sides, stretched and expanded, illuminated pitilessly. I felt it all, not just the human folk with their comings and goings, but every pigeon that fluttered in the eaves, every mouse that crept unnoticed behind the wine kegs, every speck of life, that was not and never had been a speck, but had always been a node on the web of life. Nothing alone, nothing forsaken, nothing without meaning, nothing of no significance, and nothing of importance. Somewhere, someone sang, and then fell silent. A chorus filled in after that solo, other voices, distant and dim, saying, What? Beg pardon? Did you call? Are you here? Do I dream? They plucked at me, as beggars pluck at a stranger’s sleeves, and I suddenly felt that if I did not draw away, I could come unravelled like a piece of fabric. I blinked my eyes, seeing myself inside myself again. I breathed in.

No time had passed. A single breath, a wink of an eye. Kettricken looked askance at me. I appeared not to notice. I reached up to scratch my nose. I shifted my weight.

I resettled myself firmly. I let a few more minutes pass before I sighed and shrugged apologetically. ‘I do not understand the game, I am afraid,’ I offered.

I had succeeded in annoying her. ‘It is not a game. You don’t have to understand it, or “do” it. Simply stop all else, and be.’

I made a show of making another effort. I sat still for several moments, then fidgeted absently with my cuff until she looked at me doing it. Then I cast my eyes down as if ashamed. ‘The candle smells very sweet,’ I complimented her.

Kettricken sighed and gave up on me. ‘The girl who makes them has a very keen awareness of scents. She can almost bring me my gardens and surround me with their fragrances. Regal brought me one of her honeysuckle tapers, and after that I sought out her wares myself. She is a serving-girl here, and does not have the time or resources to make too many. So I count myself fortunate when she brings them to offer to me.’

‘Regal,’ I repeated. Regal speaking to Molly. Regal knowing her well enough to know of her candle-making. Everything inside me clenched with foreboding. ‘My queen, I think I distract you from what you wish to be doing. That is not my desire. May I leave you now, to return again when you wish to have company?’

‘This exercise does not exclude company, FitzChivalry.’ She looked at me sadly. ‘Will not you try again to let go? For a moment, I thought … No? Ah, then, I let you go.’ I heard regret and loneliness in her voice. Then she straightened herself. She took a breath, breathed it out slowly. I felt again her consciousness thrumming in the web. She has the Wit, I thought to myself. Not strong, but she has it.

I left her room quietly. There was a tiny bit of amusement to wondering what Burrich would think if he knew. Much less amusing to recall how she had been alerted to me when I quested out with the Wit. I thought of my night hunts with the wolf. Would soon the Queen begin to complain of strange dreams?

A cold certainty welled up in me. I would be discovered. I had been too careless, too long. I knew that Burrich could sense when I used the Wit. What if there were others? I could be accused of beast magic. I found my resolve and hardened myself to it. Tomorrow, I would act.