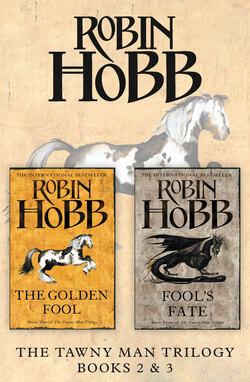

Читать книгу The Tawny Man Series Books 2 and 3 - Робин Хобб - Страница 18

EIGHT Ambitions

ОглавлениеThus every magic has its space in the spectrum of magic, and together they make up the great circle of power. All magical lore is encompassed in the circle, from the skills of the humble hedge-wizard with his charms, the scryer with his bowl or crystal, the bestial magic of the Wit and the celestial magic of the Skill, and all the homely magics of hearth and heart. All can be placed as I have shown them, in a great spectrum, and it must be clear to any eye that a common thread runs through all of them.

But that is not to say that any user can or should attempt to master the full circle of magic. Such a wide sweep of the art is not given to any mortal, and with good reason. No one is meant to be master of all powers. A Skill-user may expand his expertise to scrying, and there have been tales of beast-magickers who had mastered some of the fire-magic and water-finding skills of the hedge-wizards. As illustrated by the chart, each of these lesser arcs of magic are adjacent to the greater magics, and thus a mage can expand his powers to include these minor skills as well. But to have larger ambitions than these is a great error. For one who augurs through a crystal to attempt to master the bringing of fire is a mistake. These magics are not neighbouring magics, and the strains of supporting their differences may bring discord to his mind. For a Skill-user to demean himself with the beast-magic of the Wit is to invite the decay and debasement of his higher magic. Such a vile ambition should be condemned.

Treeknee’s translation of The Circle of Magic by Skillmaster Oklef

Looking back, I suspect that I learned more at Dutiful’s first Skill-lesson than he did. Fear and respect were what I learned. I had dared to set myself up as a teacher of something that I barely grasped myself. And so my days and nights became fuller than I had ever expected, for I must be both student and teacher, yet could not surrender my other roles as Lord Golden’s servant or Hap’s father or the Farseer’s spy.

As winter shortened the days, my lessons with Dutiful began in the black of the morning. Usually we left Verity’s tower before the true dawn lightened the sky. Both the boy and Chade were eager for us to press on, but I was determined to err on the side of caution after our near disaster.

In the same spirit, I had procrastinated against Chade’s demands that I at least evaluate Thick’s Skill-ability. I need not have bothered. Thick was as reluctant to have any contact with me as I was to teach him. Thrice, Chade had arranged for Thick to meet me in his chambers. Each time, the half-wit had not been there at the appointed hour. Nor had I lingered, hoping my wayward student was merely late. I arrived, noted his absence, and left. Each time, Thick had told Chade that he had ‘forgotten’ the appointment, but he could not hide his apprehension and distaste from Chade.

‘What did you do to him, to create such aversion?’ Chade had demanded of me. To which I had been able to honestly reply that I had done nothing. I knew of no reason that the half-wit would dread me. I was only glad that he did.

My lesson times with Dutiful were the exact opposite of that. The boy greeted me warmly and eagerly every time he arrived, and anticipated his lessons with eagerness. It amazed me. Sometimes I wondered wistfully what it would have been like if Prince Verity had been my first Skill-instructor. Would I have responded as readily as his son did to me? My own memories of Skillmaster Galen’s lessons were painful in the extreme. I had seen no wisdom in emulating his set routines and mental exercises designed to prepare a student to Skill. In truth, Dutiful seemed not to need any of them. For the Prince, Skilling was an effortless spilling of his soul. I soon wondered if I had not benefited from my own early struggles to master the Skill. I had had to force my way out past my own walls; Dutiful could not seem to find any boundaries. He was as prone to share his upset stomach with me as he was to convey his thoughts. When he opened himself, it was as if he opened the floodgate to all of the scattered and wafting thought in the world. Standing witness and guard in his mind, it near overwhelmed me. It frightened and fascinated him, and both emotions kept him from achieving full concentration on what he was attempting. Worse, when he Skilled out to me, it was as if he tried to thread a needle with a rope. Verity had once told me that being Skilled to by my father Chivalry was like being trampled by a horse: he barged in, dropped his information, and fled. So it was with Dutiful.

‘If he can master his talent, he will swiftly exceed his teacher,’ I complained to Chade one very late night when he chanced to visit his old chambers. I sat at our old compounding table, surrounded by a welter of Skill-scrolls. ‘I felt almost relief when I started teaching him Kettle’s Stone game. He found it difficult to grasp at first, though he seems to be catching on to it now. I hope it will slow him down, and help him learn to look for deeper patterns in his magic. All else seems to come to him so easily. He Skills as a hound pup instinctively puts his nose to a trail. As if he is remembering how to do it, rather than being taught.’

‘And that is bad?’ the old assassin asked genially. He began to rummage amongst the tea herbs on the high shelves. Those shelves had always been reserved for his most dangerous and potent concoctions. I smiled briefly as he clambered up on a stool, and wondered if he still supposed them safely out of my reach.

‘It could be dangerous. Once he surpasses me and begins to experiment with the Skill’s other powers, he will be venturing where I have no experience. I will not even be able to warn him of the dangers, let alone protect him.’ In disgust, I slid a Skill-scroll aside and pushed my awkward translation after it. There, too, Dutiful excelled me. The lad had Chade’s gift for alphabets and languages. My translations were a plodding word-by-word puzzling out, while Dutiful read sentence by sentence and jotted the sense of them down in concise prose. Years of absence from such work had blunted my language abilities. I wondered if I envied my pupil’s quickness. Would that make me a bad teacher?

‘Perhaps he got it from you,’ Chade observed thoughtfully.

‘Got what?’

‘The Skill. We know that you touched minds with him from the time he was very small. Yet you say the Wit is not a magic that allows that. Therefore, it must have been the Skill. Therefore, perhaps you taught him to Skill when he was a tiny boy, or at least prepared his mind to be ready for it.’

I didn’t like the trend of his thoughts. Nettle instantly sprang to my mind and a wave of guilt swept through me. Had I endangered her as well? ‘You’re just trying to make it my own fault.’ I tried to make my tone light, as if that would chase away my sudden dread. I sighed and reluctantly pulled my translation work back in front of me. If I was to have any hope of continuing as Dutiful’s teacher, I needed to learn more of the Skill myself. This was a scroll that suggested a series of exercises that a student should be given to improve his focus. I hoped it would be useful to me.

Chade came to look over my shoulder. ‘Hmm. What did you think of the other scroll, the one on pain and the Skill?’

I glanced up at him, puzzled. ‘What other scroll?’

He looked annoyed. ‘You know the one. I left it out for you.’

I gave our littered table a meaningful glance. There were at least a dozen other scrolls and papers cluttering it. ‘Which one?’

‘It was one of these. I showed it to you, boy. I’m sure of it.’

I was equally certain he had not, but I held my tongue. Chade’s memory was failing him. I knew it. So did he, but he would not admit it. I had also discovered that even a mention of that possibility would throw him into a fury that was more unsettling to me than the notion that my old mentor was not as sharp as he had been. So I silently watched him poke through the jumble of writings until he came to a scroll with a decorative blue edge. ‘See. Here it is, right where I left it for you. You haven’t studied it at all.’

‘No. I haven’t.’ I admitted it easily, hoping to avoid the whole topic of whether or not he’d shown me the scroll. ‘What did you say it’s about?’

He gave me a disgusted glance. ‘It’s about pain related to Skilling. The sorts of headaches you have. It suggests some remedies, exercises as well as herbs, but it also says that in time you may simply stop having the headaches. But it’s the note towards the end that interested me. Treeknee says that some Skillmasters used a pain barrier to keep their students from experimenting on their own. He doesn’t say that it might be made strong enough to prevent a man from Skilling at all. It interested me for two reasons. I wondered if Galen had done it to you. And I wondered if it might be a way to control Thick.’ I noticed he did not suggest it as a safety barrier for the Prince.

So we were back to Thick again. Well, the old man was right. Sooner or later, we’d have to deal with him. Still, ‘I’d be reluctant to use pain as a curb on any creature. Thick Skills out his music near constantly. Give him pain for doing that, block him from it … I don’t know what that would do to him.’

Chade made a dismissive noise. He had known I would not do it before he asked me. But I knew Galen would not have scrupled to hobble me in such a way. I wondered. Chade spread the scroll out before me, his gnarled fingers bracketing the passage in question. I read it over, but discovered little he had not already said. Then I leaned back in my chair. ‘I’m trying to remember when Skilling first started to hurt. It always left me wearied. The first time Verity drew strength from me, I fainted dead away. Any real effort with it left me almost sick with fatigue. But I don’t recall the Skill having an aftermath of pain until …’ I pondered for a time, then shook my head. ‘I can’t draw a line. The first time I Skill-walked, by accident, I woke trembling with weakness. I used the elfbark for it, then and in the times that followed. And after a time, the weakness after I’d Skilled began to be pain as well.’ I sighed. ‘No. I don’t think the pain is a barrier anyone put in me.’

Chade had wandered back to his shelves. He turned with two corked bottles in his hands. ‘Could it be because you have the Wit? Much is said in the scrolls about the dangers of using both magics.’

Was the old man trying to remind me of everything I didn’t know? I hated his questions. They were stark warnings that I was guiding my prince through unknown territory. I shook my head wearily. ‘Again, Chade, I don’t know. Perhaps if the Prince begins to have pain after Skilling, we can assume that.’

‘I thought you were going to separate his Wit from his Skill.’

‘I would if I knew how. All I can do is try to make him use the Skill in ways that force him to use it independently of the Wit. I don’t know how to make him separate the two magics any more than I know how to remove the Skill-command I set on him back when we were on the beach.’

He lifted one white eyebrow as he measured herbs into a teapot. ‘The command not to fight you?’

I nodded.

‘Well, it seems that should be a simple thing to me. Simply reverse it.’

I clenched my teeth. I did not say, ‘it only seems simple to you because you have neither magic and don’t know what you are talking about’. I was weary, I told myself, and frustrated. I should not take it out on the old man. ‘I don’t quite know how I burned the command into him, and so I don’t quite know how to lift it. “Simply reverse it” is not simple at all. What would I command him? “Fight me?” Remember that Chivalry did the same thing to Skillmaster Galen. In anger, he burned a command into him. And he and Verity never puzzled out how to remove it.’

‘But Dutiful is your prince and your student. Surely that puts you on a different footing.’

‘I don’t see what that has to do with it,’ I told him, and tried not to sound short-tempered.

‘Well. Only that I think he might help you remove it.’ He shook a few drops of something into the teapot. He paused, then asked delicately, ‘Is the Prince aware of what you did to him? Does he know you commanded him not to fight you?’

‘No!’ I did let my temper show on that word. Then I took a breath. ‘No, and I’m ashamed I did it, and ashamed to admit to you that I’m afraid to tell him. In so many ways, I’m still getting to know him, Chade. I don’t want to give him reason to distrust me.’ I rubbed my brow. ‘We did not meet one another under the best circumstances, you know.’

‘I know, I know.’ He came to pat me on the shoulder. ‘So. What have you been doing with him?’

‘Mostly getting to know him. We’ve been translating scrolls together. And I “borrowed” some practice blades from the weapons sheds, and we’ve tried one another that way. He’s a good swordsman. If the number of bruises he has given me are a fair indication, then I think I lightened my Skill-command if not erased it.’

‘But you aren’t sure?’

‘Not really. When we spar, we aren’t truly trying to hurt one another. It’s a game, just as it is when we wrestle. Still, I’ve never noticed that he holds back at all, or allows me to win more easily.’

‘Well. You know, I think it’s very good that he has you for those sorts of things. As well as the Skill-lessons. I think he was missing that sort of rough companionship in his life.’ Chade took the kettle from the hearth and poured hot water over his newest mixture of leaves. ‘I suppose only time will tell. So. Do you Skill at all with him?’

I lifted a hand to my nose. The odour from the pot made my eyes water but Chade didn’t seem to notice. ‘Yes. We’ve been doing some exercises to help him focus his magic.’

‘Focus?’ Chade swirled the pot, then put the lid on it.

‘Right now when he Skills he shouts from the top of the tower and anyone listening could hear him. We strive to narrow that shout, to make it a whisper only to me. And we work to have him convey only what he wishes to tell me, not all the information in his mind at that time. So we do set exercises. I have him try to reach my mind while he is at table and carrying on a conversation. Then we refine it; can he reach my mind, convey what he is eating, while keeping to himself who his companions are? After that, we set other goals. Can he wall me out of his mind? Can he set walls that I could not breach, even in the dead of night while he sleeps?’

Chade frowned to himself as he found a cup, and wiped it clean with one end of his trailing sleeve. I tried not to smile. Sometimes, when we were alone like this, he reverted from the grand noble to the intent old man who had taught me my first trade. ‘Do you think that’s wise? Teaching him how to close you out of his mind?’

‘Well, he has to learn to do it, in case he ever encounters someone who doesn’t have his best interests at heart. At the moment I’m the only other Skill-user he can practise with.’

‘There’s Thick,’ Chade pointed out as he poured for himself. The hot liquid splashed, greenish-black, into his cup. He regarded it with distaste.

‘I think one student is all I can deal with right now,’ I demurred. ‘Did you take any action on Thick’s problem?’

‘What problem?’ Chade took his cup over in front of the fire.

I felt a moment’s alarm and tried to conceal it by speaking casually. ‘I thought I told you about it. He was having problems with the other servants hitting him and taking his money.’

‘Oh. That.’ He leaned back in his chair as if it were of no consequence. I breathed a silent sigh of relief. He hadn’t forgotten our conversation. ‘I found a reason for the cook to give him separate quarters. Ostensibly, that’s where he works, you know. The kitchens. So now he has his own room near the pantries. It’s small, but I gather it’s the first time he’s ever had any place all to himself. I think he likes it.’

‘Well. That’s good, then.’ I paused for a moment. ‘Did you ever consider sending him away from Buckkeep? Just until the Prince has a better grasp on the Skill? There are times when his wild Skilling is a bit distracting. It’s like trying to work a complicated sum while near you someone else is counting out loud.’

Chade sipped from his revolting cup. He made a face, then swallowed determinedly. I winced sympathetically, and said nothing as he reached a long arm to seize my wine glass and wash away the taste. When he spoke, his voice was hoarse. ‘As long as Thick remains the only other Skill-candidate we have, I will not send him away. I want him where we can watch over him. And where you can try to win his regard. Have you made any efforts with him?’

‘I haven’t had the opportunity.’ I got up and brought another glass back to the table and poured more wine for both of us. Chade came back to the table. He set the teacup and the wine glass side by side and eyed them dolorously. ‘I don’t know if he’s avoiding me, or if his other duties for you simply have kept him out of my way.’

‘He has had other tasks, of late.’

‘Well, that explains his lack of care with his work here,’ I observed sourly. ‘Some days he remembers to replace the candle stubs with fresh tapers, some days he doesn’t. Some days the hearth is cleared of ashes and wood laid for the fire, and sometimes the old ashes and coals remain. I think it’s because he dislikes me so. He does as little as he possibly can.’

‘He can’t read, so I can’t give him a list of tasks. Sometimes he remembers to do all I tell him, sometimes he doesn’t. That only makes him a poor servant, not a lazy or spiteful one.’ Chade took another mouthful of his brew. This time, despite his efforts, he coughed, spraying the table. I snatched the scrolls out of harm’s way. He wiped his mouth with his kerchief and then blotted the table. ‘Beg pardon,’ he said gravely, his eyes watering. He took a gulp of wine.

‘What’s in the tea?’

‘Sylvleaf. Witch’s butter. Seacrepe. And a few other herbs.’ He took another mouthful of it and chased it down with more wine.

‘What’s it for?’ A memory tickled at the back of my mind.

‘Some problems I’ve been having,’ he demurred, but I rose and began to shuffle through the scrolls on the table. I came up with the one I wanted almost immediately. The illustrations were still bright despite the years. I unrolled it and pointed to the sylvleaf drawing.

‘Those herbs are named here as being helpful to open a candidate to the Skill.’

He gave me a flat look. ‘So?’

‘Chade. What are you doing, what are you trying?’

For a moment, he just looked at me. Then he asked coldly, ‘Are you jealous? Do you also think my birthright should be forbidden me?’

‘What?’

An odd sort of anger broke from him in a tumble of words. ‘I was never even given the chance to be tested for the Skill. Bastards are not taught it. Not until you, when Shrewd made an exception. Yet I am as much Farseer as you are. And I’ve some of the lesser magics, as well you should know by now.’

He was upset, and I didn’t know why. I nodded and said calmingly, ‘Such as your scrying in water. It was how you knew of the Red Ship attack on Neatbay all those years ago.’

‘Yes,’ he said with satisfaction. He sat back in his chair, but his hands scuttled along the table’s edge like spiders. I wondered if the drugs in the tea were affecting him. ‘Yes, I have magics of my own. And perhaps, given the chance, I’d have the magic of my blood, the magic I’ve a right to. Don’t try to deny it to me, Fitz. For all those years, my own brother forbade me even being tested. I was good enough to watch his back, good enough to teach his sons and his grandson. But I was never good enough to be given my rightful magic.’

I wondered how long the resentment had festered in him. Then I recalled his excitement when Shrewd allowed me to be taught, and his frustration when I seemed to fail and would not even discuss my lessons with him. This was a very old anger, unveiled to me for the first time.

‘Why now?’ I asked him conversationally. ‘You’ve had the Skill-scrolls for fifteen years. Why have you waited?’ I thought I knew what the answer would be: that he had wanted me to be close by, to help him with it. Again, he surprised me.

‘What makes you think I waited? But, yes, I’ve applied more effort to it of late, because my need for this magic became so desperate. We’ve spoken of this before. I knew you would not wish to help me.’

It was true. Yet if he had asked me just then, I would not have been able to say why. I avoided the question. ‘What is your need now? The land is relatively peaceful. Why risk yourself?’

‘Fitz. Look at me. Look at me! I’m getting old. Time has played me a treacherous trick. When I was young and able, I was locked up in these chambers, forced to remain hidden and powerless. Now, when I have a chance to set the Farseer throne on a firm foundation, when indeed my family needs me most, I am old and becoming feeble. My mind totters, my back aches, my memories cloud. Do you think I haven’t seen the dread on your face whenever I tell you I must look through my journals to find you a titbit of information? Imagine then how I feel. Imagine how it is, Fitz, not to have your own memories at your beck and call any more. To grope for a name, suddenly to lose the thread of a conversation in the midst of a jest. As a boy, when you thought your body had betrayed you with your fits, you plunged into despair. Yet you always had your mind. I think I’m losing mine.’

It was a terrible revelation, as if I had discovered that the foundations of Buckkeep Castle itself were weakening and crumbling. Only recently had I begun to appreciate fully all that Chade juggled for Kettricken. The enmeshing net of social relationships that formed the politics of Buckkeep had snared me, and from within its folds, I struggled to comprehend it all. When I was a boy, Chade had interpreted for me all that went on in the castle, and I had been content to accept his word on it. Now I viewed things with a man’s eyes, and found the level of complication astonishing.

And fascinating. It was like Kettle’s Stone game, played on a grand scale. Markers moved, alliances changed and power shifted, sometimes all within a passage of hours. It made Chade’s depth of knowledge all the more amazing, as he conducted Queen Kettricken’s balancing act on the shifting loyalties of the nobility. I could not possibly keep up with it all, and yet it all was interconnected.

Since I had returned to Buckkeep, I had marvelled that he could integrate it all, and dreaded the coming of a day when he could not. None of this was as easy for him as it once had been. The presence of his journals, massive volumes of pages bound flat in the Jamaillian style, were an indication that he did not trust his own memory any more. There were six identical volumes, with covers of red, blue, green, yellow, purple and goldenrod, one for each of the Six Duchies. How he determined what information belonged in each was beyond my understanding. A seventh volume, white with the Farseer Buck on the front, was where he penned his day-to-day minutiae. This he referred to most often, leafing through it for scraps of gossip or the text of a conversation or the summary of a spy’s report. Even within this secret volume hidden in the concealed chamber, he made his entries in his own cryptic words. He did not offer me access to his volumes and I did not ask it. I am sure there was much in them that I would not have wished to know. And it was safer so for the spies who toiled for the Six Duchies, for I could not accidentally betray the secrets I did not know. Yet knowing Chade feared the failing of his memory still did not explain to me what he did. ‘I know things have been difficult for you lately. I’ve worried about you. But why, then, would you tax yourself further with trying to learn the Skill?’

His hands became knotty fists on the table edge. ‘Because of what I’ve read. Because of what you’ve told me you’ve done with it. The texts say a Skill-user can repair his own body, can extend his years. How old was that Kettle you journeyed with? Two hundred years, three hundred? And she was still spry enough to take on a Mountain winter. You yourself have told me that you reached into your wolf and with it made him whole again, at least for a time. If I could open myself to your Skill, could not you do that for me? Or, if you refused, as I think you might, could not I do it for myself?’

As if he needed to show his strength of resolve, he snatched up the cup and drained it in a manful draught. Then he choked and sputtered. His lips were wet with the dark potion as he seized his wine glass and gulped the contents. ‘I notice you do not spring to offer me your aid,’ he observed bitterly as he wiped his mouth.

I sighed deeply. ‘Chade. I barely know the rudiments I strive to teach the Prince. How can I offer to teach you a magic I barely understand myself? What if I …’

‘That has been your greatest weakness, Fitz. All your life. Too much caution. Not enough ambition. Shrewd liked that in you. He never feared you, as he did me.’

As I gaped in pain at him, he spoke on, seeming unmindful of the blow he had just dealt me. ‘I did not expect you to approve. Not that your approval is necessary. I think it is best I explore the edges of this magic on my own. Once I have the door open, well, then we shall see what you think of your old mentor. I think I will surprise you, Fitz. I think I have it, that perhaps I’ve always had it. You yourself gave me the hint of that, when you spoke of Thick’s music. I’ve heard it. I think. On the edges of my mind, just as I start to fall asleep at night. I think I have the Skill.’

I could not think of a word to say to that. He was waiting for me to react to his claim to have the Skill. All I could think was that I did not feel I had ever lacked in ambition, only that my aspirations had not matched his goals for me. So the silence grew and became ever more awkward. And when he broke it, with a complete change of topic, it only made it worse.

‘Well. I see you’ve nothing to say to me. So.’ He forced a smile to his face and inquired, ‘How is your boy doing at his apprenticeship?’

I stood up. ‘Poorly. I suppose that, like his would-be father, he lacks ambition. Good night, Chade.’

And I left and went down to my servant’s chambers for the rest of the night. I did not sleep. I dared not. Of late, I avoided my bed, surrendering to it only when complete exhaustion demanded it. It was not just that I needed to spend those dark hours in my studies of the Skill-scrolls, but because when I did close my eyes, I was besieged. Nightly I would set my Skill-walls before retiring, and near nightly, Nettle assaulted those walls. Her strength and her single-mindedness unsettled me. I did not want my daughter to Skill. There was no way I could bring her to Buckkeep to instruct her, and I feared for her, attempting these explorations on her own. I reasoned that to let her through would only encourage her in her pursuit of this magic. As long as she did not know that she Skilled, as long as she thought she was just reaching out to some dream companion, some other-worldly being she had imagined, perhaps I could keep her safe. And frustrated. If I had reached back to her even once, even to push her away, I feared she might somehow grasp who and where I was. Better to leave her in ignorance. Perhaps, after a time of failing to reach me, she might give it up. Perhaps she would find something else to distract her, a handsome neighbour lad or an interest in a trade. So I hoped. But I arose each morning near as haggard as I had gone to bed.

The rest of my personal life had become equally frustrating. My efforts to get time to speak to Hap alone were no more fruitful than Chade’s arranged meetings with Thick. Either Hap never arrived, or when he did, he came with Svanja. He was completely besotted with the girl. Over a period of three weeks, I spent most of my free nights sitting in the Stuck Pig, waiting in vain for a chance to speak to Hap alone. The establishment’s draughty common room and watery beer did little to extend my patience with my son. On the occasions when Hap actually met me there, he brought Svanja with him. She was a lovely young thing, all dark hair and huge eyes, slender and supple as a willow wand, yet conveying an air of toughness as well. And she loved to talk, giving me little opportunity to get a word in, let alone address Hap privately. Hap sat beside her, basking in her approval and beauty, as she told me a very great deal about herself and her parents and her plans for her future, and what she thought of Hap, Buckkeep and life in general. I gathered that her mother was worn down by her daughter’s wilful ways and was glad that she was seeing a young man with some prospects. Her father’s opinion of Hap was not as charitable, but Svanja expected to bring him around to her way of thinking soon. Or not. If he could not accept that she would choose her own young man, then perhaps her father should stay out of her life. That seemed a fine sentiment for an independent young woman to fling boldly to the winds, save that I was a father, and I did not completely approve of this young woman that Hap had chosen. Svanja herself seemed to care little that I might not favour her attitude. I found myself liking her spirit, but disliking her disregard of my feelings.

Eventually, there came an evening when Hap arrived alone, but my only opportunity for private conversation with him proved less than satisfying. He was morose that Svanja was not with him, and complained bitterly that her father had become more stubborn about forcing her to stay in for the evenings. The man would not give him a chance. When I forcefully steered the conversation to his apprenticeship, he only repeated what he had already told me. He felt dissatisfied with how he was treated in his work. Gindast thought he was a dolt and mocked him before the journeymen. They assigned him the most boring tasks and gave him no opportunity to prove himself. Yet, when I pressed him for an example, those he gave made me see Gindast as a demanding but not unreasonable master.

Hap’s complaints did not convince me he was ill-treated. I formed a different opinion from his talk. My boy was in love with Svanja, and she was the real focus of his thoughts. Many of his repeated mistakes and his late arrivals in the morning could be blamed on this feminine distraction. I felt certain that if Svanja did not exist, Hap would be more intent, and perhaps better satisfied with his lessons. A stricter father might have forbidden him to see the girl. I did not. Sometimes I thought it was because of how such restrictions had felt to me; at other times, I wondered if I feared that Hap would not obey such a command, and so I dared not give it.

I saw Jinna, too, but coward that I was, I attempted to visit her home only when the presence of the pony and wagon indicated that her niece was likely present. I wished to slow our headlong lust even as the simple warmth of her bed was a lure I could scarcely resist. I tried. Each time I called on her, I kept my visits brief, begging the excuse of pressing errands for my master. The first time Jinna seemed to accept that tale without question. The second time she asked when I might expect to have an afternoon free. Although she made the query in her niece’s presence, her eyes conveyed a separate question to me. I evaded her, saying that my master was capricious, and would not give me a set time to go freely about my own errands. I couched it as a complaint, and she nodded her condolences.

The third time I visited her, her niece was not home. She had gone off to help a friend in Buckkeep Town who had experienced a difficult birth. Jinna told me this after she had greeted me with a warm embrace and a lingering kiss. In the face of her willing ardour, my resolve to be restrained melted like salt in the rain. With no other prelude, she latched the door behind me, took my hand and led me to her bedchamber. ‘A moment,’ she cautioned me at the threshold, and I halted there. ‘Now come in,’ she told me, and when I did, I saw the charm had been draped with a heavy scarf. She took a deep breath, like a hungry man anticipating a good meal, and suddenly all I could focus on was the surge of her breasts against the bodice of her gown. I told myself it was a foolish mistake, but nevertheless I made it. Several times. And when we both were spent and she was half-dozing against my shoulder, I made an even more foolish mistake.

‘Jinna,’ I asked her softly, ‘do you think this is wise, what we do?’

‘Foolish, wise,’ she had sleepily responded. ‘What does it matter? It harms no one.’

Her question was asked lightly, but I answered seriously. ‘Yes. I think it does. Matter, that is. And perhaps does harm.’

She heaved a heavy sigh, and sat up, brushing her tousled curls from her face. She peered at me near-sightedly. ‘Tom. Why are you always so determined to make this a complicated matter? We are both adults, neither of us is vowed to another, and I’ve promised you that you cannot get me with child. Why should not we take a simple, honest pleasure in one another while we may?’

‘Perhaps for me, it feels neither simple nor honest.’ I struggled to make my reasons sound sensible. ‘I do what I have taught Hap is not right to do: to be with a woman I have not pledged myself to. Did he tell me today that he was doing with Svanja what we have just done, I would rebuke him severely, telling him he had no right to –’

‘Tom,’ she interrupted me. ‘We give our children rules to protect them. When we are grown, we know the dangers, and choose for ourselves what risks we take. Neither you nor I are children. Neither of us is deceived about what is offered by the other. What danger do you fear here, Tom?’

‘I … I dread what Hap would think of me, if he found out. And I do not like that I deceive him, doing that which I forbid him to do.’ I looked aside from her as I added, ‘And I would that there was more to this than just … adults taking a risk for pleasure.’

‘I see. Well, perhaps in time, there may be,’ she offered, but there was an edge of hurt in her voice. And I knew then that perhaps she had deceived herself as to what we shared.

What should I have replied? I don’t know. I took the coward’s part and said, ‘Perhaps in time there will be,’ but I did not believe my own words. We lingered a while longer in bed, and then rose to share a cup of tea by her fireside. When at last I told her I must go, and then lamely insisted that I could not tell her a specific night when I could call again, she looked aside and said quietly, ‘Well, then, come when you’ve a mind to, Tom Badgerlock.’

And with those words she gave me a parting kiss. After her door closed behind me, I looked up at the bright stars of the winter night and sighed. I felt guilty as I began my long walk back to Buckkeep. I was cheating Jinna out of something, not by denying her a false avowal of love, but by accommodating our attraction. I doubted that I would ever feel for her anything more than I felt right now. Worst was that I could not promise myself I would not continue to see her, even though a lusty friendship was all I could ever offer her. I did not think well of myself, and felt worse as I forced myself to admit that Hap probably guessed that I now shared Jinna’s bed from time to time. It was a poor example to set for my boy, and the road back to Buckkeep Castle seemed very black and cold that night.