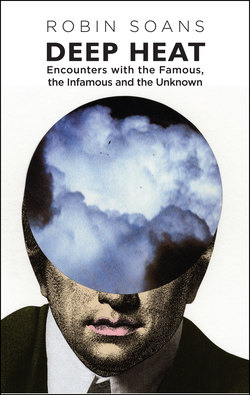

Читать книгу Deep Heat: Encounters with the Famous, the Infamous and the Unknown - Robin Soans - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

EDWINA

I was researching Life After Scandal when I met Edwina Currie. Matthew Parris had already told me that you couldn’t meet her without being impressed by her sharp intellect and insight. I phoned her up and she said, ‘Alright, I’ll meet you at the Atrium next Tuesday at twelve o’clock…it’s opposite the Houses of Parliament. I’m on air at two o’clock but that should give us two hours. I’ll talk about salmonella, but I’m not going to talk about John Major. I’ll leave you to do the booking.’

The Atrium has something of a Spanish holiday resort about it…a lot of pot plants, light filtering down through a glass roof…and we sat on a raised balcony above the main body of the restaurant, which would have been a swimming pool if it was a hotel. I was there in plenty of time, with my red book…I use large red A4 size notebooks and rapid-flow pens…very rapid flow when you have someone as articulate as Edwina Currie to interview…and a glass of fizzy water. I was the only person in the restaurant.

Edwina arrived exactly on time; and as it turned out talked only about John Major. I was impressed by her…and I thought but for circumstance she would and should have played a more significant role in public life. She would be much better employed sorting out social problems in inner cities than appearing on Celebrity Wife Swap.

THE POISONED CHALICE

Edwina (50s) sits at a restaurant table. She has a menu in her hand. There is a glass of fizzy water on the table.

EDWINA: I was completely flabbergasted when the call didn’t come. I liked him. I trusted him. We’d had an affair for four years from 1984 to March 1998. (The waiter appears at her side.) Yes, I’ll have the soup and then the goat’s cheese tart and tomato salad… thanks a lot. (The waiter takes the menu and goes.)

I didn’t stop it because I didn’t love him any more…not at all. He was now Chief Secretary to the Treasury, maybe heading for even higher office. People might start asking the wrong questions… ‘What’s a cabinet minister doing, going up the stairs to a back bencher’s flat?’ I certainly didn’t want to do anything to damage his career, or, obviously, mine. You know we used to arrange our dates sitting on the Front Bench in the House of Commons, whispering to each other. We got a lot of fun out of that.

In December 1990 John was elected. I naturally assumed he would put his friends into office. I sat there waiting for the phone to ring. It never did. I was very, very, very upset.

When we won the election in 1992 with a much reduced majority, a nasty bruising election, the next day I was in the gym, on a rowing machine, looking up at the banks of TV sets, watching all the appointments being made. No call. I got a call late the following day. I was summoned to Number Ten. I took the tube to Westminster Station, walked across the lights to Whitehall trying not to get killed by the traffic, walked down Downing Street, said hello to the police officer…the door opens as you arrive; what happened with Margaret Thatcher…you were ushered into a small room, and she would talk to you very informally…closer than we are now…it was always very personal; and it was like that when you got the sack as well. Anyway, I found myself not in this small room, but in this large drawing room, the White Drawing Room, on a sofa opposite two men on another sofa…one was the Prime Minister, and one was Andrew Turnbull, the PM’s Private Secretary. I looked at this man Turn-bull and thought, ‘What the blazes are you doing here?’ It meant John and I couldn’t have a proper conversation for a start. The Prime Minister said ‘Edwina, I’d like you to join the Government, and I’d like to offer you the job of Minister of State in the Home Office.’ I said, ‘What does it involve?’ Andrew Turnbull said, ‘We want you to be Minister for Prisons.’ I said ‘I’ve got a couple of prisons in my constituency. I know what a terrible state they’re in.’

Prisons…of all the jobs on offer it was going to be the poisoned chalice, and whoever drank from that cup was soon going to be sacrificed in a blaze of publicity so the rest of them could carry on. I said, ‘Thank you but no thank you. Isn’t there anything else?’ John Major said, ‘You were not around when we tried to phone you’ and I said, ‘When was that?’ and he said, ‘Earlier today’ and I thought, ‘That’s a lie’ and then he said, ‘You can’t say ‘no’, I’ve put it out in a press release.’ I thought, ‘You prat.’ I said, ‘Can I ask you something? Why couldn’t you put me in office when you were first made Prime Minister?’ And John Major said, ‘I’d forgotten about you.’ And I thought, ‘You double prat.’ There I was on that sofa looking at someone I’d been so close to so recently, thinking it was reasonable to expect a modicum of special consideration…and there he was blandly smiling and saying, ‘I’d forgotten about you.’ And I thought to myself, ‘One day you will remember.’ Turnbull was smoking…he was smoking and smiling…he thought the interview was quite funny.

I walked out of Number Ten. I was wearing a black coat, a rather smart black coat I bought in a second-hand shop in Paris…I was wearing this black cashmere coat, and all the photographers were there, and I’m sure my ministerial car and driver were waiting to whisk me off to the Home Office, and I walked back down the pavement looking like the black widow in the advert for Scottish Widows. I re-ran the scene in my mind as it should have gone. We would have met in a small private room, just the two of us. He would have kissed me and then said, ‘There are three or four jobs still vacant, these and this and this, Edwina…do you have a preference?’…looking deep into my eyes…I would have said, ‘The one which is for the country’s good…and you know I’m particularly good with inner cities’ and we would have had a serious conversation.

I must have walked home…like the Queen I walk quite a lot…but you don’t remember the walk when your brain is thinking, ‘What’s going on?’ There had been no personal contact between us. He hadn’t a clue…hadn’t a clue that I was hurt; he couldn’t see it was the be-all and end-all of my life to join the government and be put in a position where I could make a good job of something. The only feeling I was left with was betrayal… a feeling of something totally irreversible. A Rubicon had been crossed; that was the damage done then…at that moment…it sowed the seed for something that would happen many years later…I thought ‘One day when it won’t damage the party, I’m going to put the record straight in as simple and unadorned fashion as possible, from notes I made at the time. The truth will out, and I will be the architect of that truth.’ I think it’s important to pass on history as accurately as possible. Minister for Prisons. He might as well have handed me the dagger there and then.