Читать книгу Deathscent: Intrigues of the Reflected Realm - Robin Jarvis - Страница 12

CHAPTER 3 Lantern Illuminates

ОглавлениеThe interior of the barn bounced with light as sharp tongues of flame lapped around the fallen beast. Still quaking and trembling, the mechanical lay upon the floor, plumes of blue smoke rising from every warped and gaping crevice.

At the threshold, all eyes gazed on Master Edwin’s stricken corpse but not many could bear to look at him for long. The most learned master of motive science in Suffolk was dead, and for several moments the only sound was the harsh clicking and grinding of his mechanical destroyer. The people gathered around were too distressed and aghast to utter a word.

Sir Francis Walsingham’s calm, cold features betrayed nothing but, beside him, his secretary was almost wilting, covering his face with jittery hands. Sorrow and compassion were graven in Doctor Dee’s solemn, white-bearded countenance, yet when he shifted his glance to the collapsed horse, fierce curiosity assumed their place.

Met with the sobering sight of his dead servant, Lord Richard Wutton searched for Mistress Dritchly in the crowd.

Master Edwin’s widow was not among the assembled faces and, looking back at the house, he saw the plump, prim-looking woman, with her greying hair tied up in curling papers, come bustling towards them.

“Jack,” Lord Richard said hastily. “Go to her – she must not see her husband thus. Take her back indoors.”

Dragging himself away from the stunned group, the apprentice nodded and hurried to obey.

Henry Wattle’s eyes were bulging from his head. “Squashed and stamped on!” he breathed. “You could slide the bits under a door.”

“Don’t,” Adam balked.

“Fetch a cloak to cover him,” Lord Richard commanded, and Henry scampered away. Then, with a face as grim as the appalling scene before him, the master of Malmes-Wutton glared at his distinguished guests and strode to confront them.

Sir Francis Walsingham and Doctor Dee had already stepped over the dead man’s crushed body. Remaining at a safe distance, their black and red figures peered at the quivering mechanical horse through the billowing blue reek which bled from every opening.

Into this fog Lord Richard went wading. “A man is dead!” he roared. “Yet all you care about is your vile charger! What manner of ice-blooded creature are you?”

Walsingham waved a silencing hand which only served to enrage his host all the more. “This tragedy would never have happened if it were not for you,” he cried.

Sir Francis ignored him and gave a signal to his secretary. With a handkerchief of Holland cloth clamped over his mouth and averting his eyes from the gruesome spectacle, Master Tewkes tiptoed into the barn.

“Lord Richard,” he began, spluttering in the smoke and the sharp stench of scorched metal. “Do you not see? Yet another skilled craftsman has met with an unlikely accident. This is not the work of unhappy chance – it was purpose meant and blackly done. Your man has been murdered.”

For an instant Richard Wutton’s anger was quelled as he struggled with this awful revelation. The secretary seized this opportunity to expound.

“Verily!” he declared. “Here again do we see the malevolent ministries of the hated Catholic powers. This is assassin’s work! May the Lord visit his vengeance upon their evil heads!”

“Tewkes!” Walsingham scolded. “If you can curb the damning of our enemies for a moment, make yourself of use and send that melancholy audience away.”

Tucking the handkerchief into his sleeve, the secretary turned to face the gathered members of Lord Richard’s household. “Be off with your morbid goggling,” he told them. “There is naught you can do for Master Dritchly now. We shall attend to what must be done.”

The servants shifted uncomfortably but made no move until Lord Richard added, “Go – pray for Edwin’s soul, my friends.”

Slowly the group drifted back to the manor, but Adam o’the Cogs was reluctant to leave and lingered at the threshold.

Nursing a badly grazed arm and hobbling upon an injured foot, the groom returned to the barn and Master Tewkes eyed him with undisguised hostility.

By now the choking vapour had thinned to a haze and Doctor Dee edged closer to the fallen horse. Faint tremors still shivered across Belladonna’s battered form, but the flames were dying and the astrologer stooped over her to prise one of the contorted sections free. A fresh cloud of smoke rose from inside and he held his whiskery face clear until it dispersed.

“Now,” he said, bending over the hole he had made, “let us see how this wickedness was achieved.”

“Permit me, My Lord,” Jenks said, limping towards him. “I know the workings better than any.”

Master Tewkes thrust out his hand to prevent the man from going any further. “You remain where you are!” he objected, his voice loaded with reproach and accusation. “You have engineered enough this night.”

Startled by the charge, Jenks backed away in fright. “You cannot think I was responsible for this,” he gasped. “My hands are clean of any blame.”

“Was it Spanish gold or French which bought your base treason?” Tewkes persisted. “A quartering is too merciful a punishment for you!”

The groom turned pale and he stared imploringly at Sir Francis. “It is not true!” he denied. “On my life it is not!”

Peering over Doctor Dee’s shoulder, Walsingham did not even look up at him. “I will listen to neither plea nor indictment till we have determined what truly happened here this night,” he said. “What have you learned from this wreckage, Doctor?”

The astrologer raised his head and drummed his slender fingers irritably upon one of the steel flanks.

“Alas!” he confessed. “My limited knowledge of the new stars is greater than my understanding of this once noble charger’s internals. ’Tis a grievous pity that the one man who could aid us was the beast’s victim.”

Covering Master Dritchly’s body with the cloak that Henry had just brought, Lord Richard snorted with contempt at the scholar’s apparent lack of concern. “Grievous indeed!” he said.

Hearing the talk, Adam plucked up his nerve and stepped into the barn. “Beg pardon, My Lords,” he began, “but I may be able to assist.”

Everyone stared at him and in the accompanying silence the boy wished he had not volunteered but had waited instead for the return of Jack. Lingering by the door, Henry watched in admiring fascination. He would never have dared approach those nobles and he suspected that his friend had just earned himself a whipping.

“You?” the secretary snapped in amused disbelief. “What can a cog urchin possibly …?”

“I know how to put a cow together, make it walk and eat so its bags fill with milk,” Adam retorted impulsively. “Which is more than you do.”

Master Tewkes gave a shout of indignation and raised his hand to strike the insolent boy.

“Wait!” Lord Richard intervened. “The lad’s mine to deal with – not thine, Master Secretary. If any discipline is needed, it’ll not be measured by your hand.”

Tewkes’ nostrils flared in outrage and his bird-like head darted aside, looking to Sir Francis for support. “Let the boy approach,” came Walsingham’s astonishing response.

Leaving the secretary fuming behind him, Adam crossed to where the great mechanical lay upon the ground and knelt before it. The metal was still hot. His face tingled in the baking airs and his fair hair rippled as he leaned over the opening that the astrologer had made.

“Bum boils,” he murmured, unconsciously using a favourite phrase of Henry’s. Never in his life had he seen such a mangled confusion of workings. Within the stricken creature all was twisted and blackened. Strands of stinking smoke curled up from the inaccessible recesses where occasional sparks still spat and sizzled, but there was no more danger and Adam lowered his head inside for a more thorough inspection.

Along the horse’s length, a few brass wheels were still spinning, but others were fused and welded to their spindles. Springs were stretched and distorted, the teeth of every cog had been worn smooth, levers were bent and broken, and the four pendulums which Belladonna boasted had actually been melted out of shape.

“This was no shaking sickness,” he declared. “Master Dritchly never told of this happening.”

An indulgent smile lifted the corners of Doctor Dee’s white beard. “What then?” he asked. “Enlighten us.”

Gingerly reaching his hand up inside the neck, the apprentice felt along the bellows pipe and winced when his fingers burned on a fragment of smouldering metal. Cursing under his breath, he proceeded until his stinging fingertips found what he was seeking.

“The ichors are there,” he said, “but the vessels are all cracked and broken. The cordials have leaked out and boiled away.”

A puzzled frown scrunched the boy’s brow.

“What is it?” the astrologer asked.

“Not sure. There seems to be something else here … if I can only …”

Master Tewkes folded his arms and tutted peevishly. “What use is this?” he complained. “The young idiot is making geese of us all.”

“Here!” the boy exclaimed, extracting a small glass phial from the horse’s insides. “It was attached to one of the ichor pipes – definitely doesn’t belong there.”

Taking it from him, Doctor Dee walked over to where a lantern hung on the wall and examined the vessel in detail. The bottle was spherical in shape, with a tapering neck tipped with a barbed, silver needle which appeared capable of piercing the toughest leather. Inside the phial were the dregs of a dark, indigo-coloured liquid and the old man sniffed them tentatively.

Thoughtful and silent, he passed it to Walsingham and the Queen’s spymaster received the object with great solemnity.

“Is it as we feared?” he asked.

Doctor Dee inclined his head. “It is,” he answered. “The enemies of Englandia have contrived a way of distilling a new and deadly ichor.”

“Then the intelligence furnished by my agents in Europe was correct,” Walsingham reflected. “With this mordant liquid those hostile powers can transform any mechanical into a killing engine.”

The old astrologer looked questioningly at Adam. “In your opinion,” he began, “how long would the effects of this loathsome venom take to work its evil within such a creation as that horse?”

“Can’t tell you that, Sir,” the boy replied, taken aback to be treated with such respect from so important a figure. “I never seen nothing like it before.”

“Your finest guess then?”

Adam looked in at the extreme damage once more and shrugged. “Not long I don’t reckon,” he said finally. “To pump round all the feeder veins wouldn’t take no more than a quarter hour.”

“Remarkable boy,” the Doctor observed.

Weighing the glass vessel in his palm, Sir Francis brought his piercing glance to bear upon the groom and the man struggled to proclaim his innocence.

“No other has been near the horses this night!” Walsingham said, his assured, level voice more daunting than any shouted threat. “Who else could have done this?”

“As God is m–my witness …” Jenks stammered.

“Search him and his belongings,” Walsingham commanded.

Eager to obey, Master Tewkes snatched a leather purse from where it hung at the groom’s waist and emptied the contents into his eager hand. “Ha!” he proclaimed, casting groats and pennies to the ground but brandishing a small object with a jubilant flourish. “Behold – the knave’s guilt is proved beyond further doubt.”

Held between the secretary’s fingers was a second phial of glass, identical to the one Adam had discovered – yet this one was full.

“Who can say for whom this was meant!” Master Tewkes cried, shaking the blue fluid within. “One of Her Majesty’s own steeds perhaps?”

Jenks stared at the bottle with a look of horror etched into his face. But, before he could voice any protestation, Doctor Dee prowled forward, his keen eyes sparkling.

“Your next words may condemn you,” he warned. “So choose them with wisdom. Tell me truthfully, what happened here this night?”

Jenks blinked and nodded at the other mechanical horses which were still standing at the darkened end of the barn.

“I saw to the beasts,” he said. “Unloaded them, polished the dust away, brushed the manes and tails then sat and ate the bit of supper the kitchen girl brought out to me.”

“Is that all?”

The groom nodded. “It was then that Belladonna started. A frightful noise she made.”

“No, no, no,” the astrologer remarked with a disappointed air. “That will never do. Like many puzzles this is merely a question of mathematics. You have left out the most significant factor in your account.”

Jenks shrank against the wall, looking like a cornered animal of the old world about to be delivered to the wolves. “It’s true I tell you!” he cried wretchedly. “Every word.”

Master Tewkes spat at him. “The rack will teach you the meaning of truth,” he promised.

“Hold!” Doctor Dee’s voice rang sharply. “I had not finished, hear me out.” He waited until he had their complete attention, then continued. “Observe the groom’s appearance,” he said. “Does it not speak of more than he has related?”

“I always thought he looked like a surly gypsy!” the secretary put in, unable to stop himself.

A warning glance from Walsingham caused Master Tewkes to bite his own tongue and say no more.

“Note the particles of straw in this man’s hair,” Doctor Dee resumed. “There is also a quantity upon his back; is that not suggestive? Look also to the great heaps piled yonder – mark you that singular depression?”

He indicated the hills of straw kept at the back of the barn. Upon the lower slopes there was a curiously deep hollow.

“The fact you omitted to tell us,” he said, returning his attention to the groom, “is that you fell asleep. Replete with Mistress Dritchly’s victuals, you sat at your ease and were awakened only when Belladonna began making those horrible sounds. No doubt there were preliminary whirrs and other signs of distress, but you missed them entirely until they were loud enough to rouse you from slumber. Perhaps in all the confusion you did not realise you had even closed your eyes, but it is the only hope of salvation you have for the moment.”

Walsingham pursed his lips and considered what the astrologer had said. “Then some other party may have stolen into this place and tampered with the horse,” he said. “It is possible.”

“Fanciful nonsense!” Master Tewkes blurted. “The groom had the other phial in his keeping. Of course he is the one! He was the only person here this night and he is responsible!”

To everyone’s surprise, the Doctor gave a slight chuckle. “Oh no,” he corrected. “There you are mistaken. As I have said, the solution to this enigma is mathematical in nature. I shall demonstrate how, in this instance, one plus one can equal three. Jenks was not alone in the barn – there was another.”

Stepping aside he lifted his lined face and called out, “Lantern!”

Still kneeling by the ruined wreck of Belladonna, Adam picked up the light that was nearby and offered it to him. Doctor Dee declined with an amused smile and pointed to the shadow-filled corner of the barn, beyond the remaining horses.

“The illumination I seek,” he said, “is of another sort.”

Everyone stared. Standing by the entrance, Henry peered around the door and held his breath.

From the gloom he heard a rustling. There, in the dun murk, one of the straw mounds was moving. It shook and wobbled for a moment, then a dark shape clambered free and Jenks choked in fright.

“The imp from Hell!” he breathed.

Both Henry and Adam recalled what the groom had told them about Doctor Dee. Over there in the unlit corner, a small, dwarf-like figure was brushing the dust and hay from its shoulders, then through the shadows it came.

“Gentlemen,” the old astrologer announced, “permit me to introduce my own personal secretary – Lantern.”

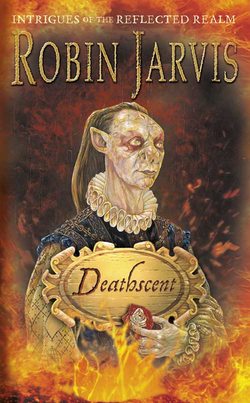

The squat shape ambled towards them, the discs of its eyes glowing with a pale green radiance. Adam gazed at the stranger in wonder. It was a mechanical, but the most peculiar one that he had ever seen.

Fashioned in the shape of a short, round man, Doctor Dee’s secretary was wrought almost entirely from copper. The head was a gleaming globe and, apart from the large circular eyes, the only other feature was a hinged hatch in place of the nose.

The body was also hammered out of the flame-coloured metal, forming a tubby doublet with rivets for buttons, and a high collar with a crimped and corrugated edge. Scarlet velvet covered the arms and legs, and the hands were protected by white gauntlets. A conical hat, almost as tall as the rest of him, sat on top of the domed head and Adam was intrigued to see that a grilled window was cut into the front. It was too dark to see what, if anything, was within.

Standing before the astrologer, the outlandish creation executed a low, courteous bow and three copper feathers affixed to a riveted band about the hat scraped over the floor.

“Good evening, Lantern,” Doctor Dee greeted as warmly as if addressing a real person. “I trust your journey here in the travelling chest was not too disagreeable?”

Not even the most expensive mechanicals had the power of speech. Lantern’s burnished head slid from side to side, then the secretary bowed once more.

“Tell me,” the astrologer said, “have you witnessed all that occurred this night?”

Lantern nodded and the trio of feathers jiggled up and down.

Doctor Dee indicated the fearful groom. “Did Jenks commit this dastard crime?” he asked.

The mechanical gave a forceful shake of its head, and the groom sank against the wall, sobbing his gratitude.

“I was convinced as much,” the old man muttered. “What, then, were the circumstances of this tragedy?”

Executing another bow, Lantern trotted over to the four remaining horses and began to mime the events he had seen. Reaching as high as his diminutive stature allowed, he pretended to polish their flanks and brush the tangles from their tails.

It was rather embarrassing for Jenks because the mechanical repeated everything he had observed in accurate detail. He was adept at mimicking the groom’s mannerisms and copied the arrogant jaunty swagger perfectly. It was soon proved, however, that Jenks adored the horses in his care, for Lantern kept throwing his arms about them in a fashion which appeared quite absurd and comical.

Then, with a nimble hop, he sat cross-legged on the ground and shovelled imaginary food into his non-existent mouth, wagging his head and rubbing his copper stomach as if enjoying it heartily.

“The supper was to your liking I see,” the Doctor remarked to the groom.

Jenks managed a weak smile; the provisions had been tastier than anything he was accustomed to.

Lantern stretched up his arms as though fatigued, then rose, inspected the horses again, and wandered over to the straw where he eased himself down and lay in precisely the same hollow that Jenks had created earlier.

Walsingham shot the Doctor an impatient glance. “A very pretty mummery,” he said. “But what happened then?”

The mechanical bobbed up again and shook off the persona of the groom. Striding to the entrance he assumed a new role and came sneaking into the barn, looking this way and that and advancing with nervous, jerky movements.

“Now we have it,” Doctor Dee declared. “The third player in this lethal equation.”

Lantern stole over to the empty impression in the straw, rubbing his gauntleted hands together as he had seen the malefactor do before. Taking pains not to make any sound, he performed the planting of the incriminating bottle in the sleeping groom’s purse, then turned to where Belladonna had stood.

Holding out his small hands to appease and calm the high-spirited steed, he stalked towards the now empty spot, his copper shoulders shaking as if with mirth. Deftly, his palms travelled across unseen contours until, with an expert twist which had obviously popped one of the steel plates free, he reached up, holding something carefully between his fingers.

“Enough,” Walsingham rapped. “The rest is plain. Who, then, is responsible?”

The burlesque over, Lantern took a side step to cast off the villainous character. Returning to his master, his round head revolved slowly in order to survey everyone present.

From the door, where Henry was still standing, those green lenses panned through the barn. Over Master Tewkes they roamed, then Jenks, Lord Richard, Adam and the remains of Belladonna, until at last they rested upon Sir Francis Walsingham.

“Is the rogue present?” the Queen’s advisor demanded.

Lantern bowed then walked purposefully towards the entrance. Watching him approach, Henry Wattle began to splutter, but there was no need to be alarmed, for the copper figure veered aside and pointed an accusing finger at Master Arnold Tewkes.

“What game is this?” the man exclaimed in an injured voice. “Get away from me, you walking kettle!”

The mechanical stood his ground.

“Tewkes,” Walsingham hissed. “What have you to say?”

“Only that I find no jest in this. Remove this clunking hobgoblin at once, before I lose my temper.”

Lantern continued to point. Master Tewkes snorted angrily and lashed out with a vicious kick which sent his denouncer staggering back.

“Explain yourself!” Walsingham growled.

Master Tewkes drew himself up. “Surely, My Lord,” he objected, “you are not serious in this? I have served you faithfully for many years, yet you are ready to accept this silent clowning as evidence against me. I am dismayed and affronted.”

“Lantern is never mistaken,” Doctor Dee said firmly. “His vision is often deeper and clearer than mine own.”

“He is at fault, I tell you!” Tewkes denied hotly.

The mechanical shook its head and again the finger pointed. Incensed, the furious man sprang forward, pushing Lantern off balance then leaping on top of him. In an instant he had wrenched the copper breastplate away and spat upon the exposed, delicate workings.

The little figure flailed beneath him as Master Tewkes raised his fist to smash the glass vessels of the controlling ichors. “You’ll accuse no more!” he ranted. “A pan for stewing cabbages is all you’ll be fit for when I’m done.”

Before the threat could be carried out, Doctor Dee and the groom dragged him clear, and Jenks pinned him against the wall. Master Tewkes struggled and demanded to be set free; then he caught sight of Walsingham’s grim face and his efforts ceased. A wintry light was glinting in Sir Francis’ dark eyes.

“You knew,” he breathed, bewildered. “You have suspected me all along.”

“Not all along,” Walsingham confessed. “Your singular condemnation of all Popery did kindle my initial suspicions, for they were such ardent damnings that they left a bitter tang upon even my Puritan palate. Yet gradually I learned of your treachery and collated as much intelligence pertaining to it as was possible.”

“How much?”

Walsingham’s eyebrows bunched together. “You are in the employ of Spain,” he stated. “You were indiscreet enough to be observed at a clandestine meeting with the ambassador, the Count de Feria, on two occasions during the past five years. Yet I have further proofs than that and expect many more still.”

Master Tewkes turned pale. “There is no need for torture,” he said quickly. “I will tell you everything.”

“Oh, I know, but it’s tidier this way, don’t you think? You were always such a zealous clerk that I am certain you understand. A tickle of torture to give veracity to your statements, and then …”

“Then?”

Sir Francis permitted himself a grave smile. “The Tower,” he snarled.

“No!” Master Tewkes yelled in terror. “Not there! I beseech you, My Lord! I would rather die a hundred deaths.”

“One will suffice,” Walsingham said coldly. “The Tower it is.”

“Never!” the man cried in panic, and with a shriek he stamped violently upon Jenks’ injured foot. The groom recoiled, and in that brief moment of liberty, Master Tewkes snapped the neck of the bottle containing the indigo ichor and poured the liquid down his own throat.

A wild, dangerous look clouded his face as the fatal juice trickled into his stomach, and his stained lips blistered immediately. “I’ll not go to that doom!” he cried, his voice rising to a high, mad laugh. “Though you, My Lord, may shortly be consigned there. The time of Elizabeth, the misbegotten usurper, is over! The crown of Englandia will be cast from Her head. Philip will reign here. This uplifted world is for the true Catholic faith – not your filthy heresy. It must be cleansed of your infection, as God plainly wills …”

The secretary shuddered as an agonising spasm seized him and he gripped his stomach feverishly. The venomous ichor was scorching his insides and he dropped to his knees, convulsing in torment.

Lord Richard hastened over to him but Master Tewkes was beyond rescue. Dark blue vapour trailed from his nose and mouth and, emitting a last gurgling cry, the traitor fell on his face and expired.

Richard Wutton knelt beside the dead man, whose features had assumed a hideous, chalk-like pallor. The master of Malmes-Wutton looked across to the crushed corpse of Edwin Dritchly lying by the barn entrance. It had been a night of horrors and countless emotions broiled inside him.

“I did not expect that,” Walsingham said dryly. “There was much he could have told us – what a squandered opportunity.”

Doctor Dee agreed. “I did not foresee what other purpose the malignant ichor might be used for,” he murmured. “We must be doubly vigilant. ’Twould seem our enemies have been most busily occupied.”

“They are massing their strength, constantly devising new weapons of destruction. My spies in the Spanish court have recently despatched reports of mechanical torture masters, diabolic instruments which only a Catholic mind could envisage. I would dearly like to obtain a copy of the plans.”

Lord Richard could endure it no longer and his simmering rage finally burst forth. “Listen to you!” he snapped. “You chatter and squawk whilst two men lie dead, and pick over their carcasses like carrion birds. This ridiculous visit was orchestrated solely for the purpose of unmasking your secretary. The blood of Edwin Dritchly besmears you both.”

Walsingham regarded him with faint surprise. “I regret the death of your craftsman,” he drawled in his usual composed and maddeningly detached manner. “But it was necessary to capture Tewkes as far away from court as possible. You still do not realise the perilous state of affairs. There was simply no other way.”

Lord Richard could not bear to look at him. “I want you gone,” he ordered. “Now that your odious mission is complete, you are to leave my lands. Get from this place, you are no longer welcome.”

Sir Francis was already striding for the entrance. “You were always an emotional fool, Richard,” he reflected. “To buy the safety of Her Majesty and ensure the welfare of Her blessed realm I would gladly sacrifice any number of lives.”

“Then I pity your conscience,” Lord Richard murmured and he turned his back on him.

Walsingham’s tall black figure departed, but Doctor Dee remained. “I told you this was not of my doing,” he said.

“Spare me your hypocrisy, John,” Lord Richard retorted. “May another fourteen years go by before we see one another again. You spend the lives of my friends too freely.”

The astrologer fell silent and motioned to Lantern to follow him. Still sitting upon the floor, occupied in the task of replacing his own breastplate, the little figure rose to his feet. Only then did they realise the damage caused by Master Tewkes’ savage kick.

The mechanical’s right leg was buckled and bent backwards. Peering down, Lantern gave the disfigured limb an experimental shake and the green light dimmed in his eyes when there came a tinkling rattle of fragments that clattered down into his boot. Abruptly the leg gave way beneath him and, with a clang, the copper man sat down again.

“My dear fellow,” Doctor Dee exclaimed, offering him a hand. “Can you not walk?”

His leg twitching pitifully, Lantern gave him a forlorn look then hung his head.

“Take it to the workshop,” Lord Richard said with some reluctance. “I’ll send Jack Flye to deal with it.”

The colour rose in the astrologer’s face and he thanked his host for this last kindness.

Richard Wutton went stomping from the barn. “I go now to speak with Mistress Dritchly,” he said tersely. “When that painful interview is over I will expect to find that you and Walsingham have gone.”

A short while later, Jenks had readied the remaining horses. The body of Master Tewkes had been slung over the beast that had carried him to Malmes-Wutton and Sir Francis Walsingham was impatient to be away. Master Dritchly’s remains had been respectfully removed into the manor.

Within the stables, Lantern was sitting upon Jack Flye’s workbench, keenly watching the boy repair his leg.

“Nasty bit of harm done here,” the seventeen-year-old declared. “Don’t think it can be mended back to what it was before. Need a whole new limb, this will.”

Casting an interested eye over the impressive array of tools gathered in the workshop, Doctor Dee tutted into his long white beard. “How inconvenient,” he muttered. “Such skilled work requires time. I rely upon my secretary a great deal. His assistance is invaluable to me, as is his steadfast companionship.”

Jack scowled. “Master Dritchly might have been able to do it,” he said with undisguised reproach. He resented having to work on anything belonging to those who had caused Edwin’s death and he was tired after so long and bitter a day.

The other apprentices were leaning on the bench, watching. Although the hour was late and they were both drained after the night’s awful events, they were also eager to see the inside workings of this wonderful creation. Never had they seen such cunning devices; there was a delightful harmony of swinging weights and clicking levers. Wheels spun smooth and silent, while brass chains slipped gracefully across their gears. It was all ingenious and engrossing, but the most fantastic element, which drew a long, low whistle from Henry, was the quantity of ichor.

The three usual humours were there in long glass cylinders, but next to them was an even larger vessel containing the black cordial – the most expensive of all.

“This mannikin must be smarter than all of us put together,” Henry marvelled.

“Imbeciles,” the Doctor commented, “whether human or not, are tiresome society.”

As the minutes passed, Henry began to nod, but Adam was becoming concerned at Jack’s treatment of Lantern. He was being inordinately rough and ham-fisted. Where gentle, persuasive tappings with a small hammer were required, the older boy bashed and bullied the damaged metal as though venting his anger and frustration.

Despite being brutalised in this way, Lantern remained quietly tolerant and suffered every fresh attack with remarkable forbearance. He even assisted Jack by passing him the tools he needed and at last Adam saw what was kept inside the tall, conical hat.

It was a stout candle and, now that it was lit, tiny punctures were revealed over the whole copper surface from which the warm light pricked and twinkled, casting a field of fiery stars across the wall.

“Is that where he gets his name from?” Adam asked.

Doctor Dee said that it was not, but he explained no further for he was also beginning to realise that Jack was applying more force than was entirely necessary. Sternly, he drummed his fingers on the bench until the boy moderated his technique.

“That’s the best I can manage,” Jack said at last. “If I carry on it’ll be doing more harm than good.”

Lantern was lifted from the bench and set on the floor. But when he tried to walk, he limped so badly that Jack actually looked guilty and embarrassed. The small mechanical hobbled gamely about the workshop, tottering unsteadily between the disassembled sheep and cows which still littered the place. When eventually he halted before his master, he shook his head in such a dejected fashion that Adam felt sorry for him.

“It’ll need proper attention when you get to London,” Jack said.

The Queen’s astrologer gave a curt nod and led the faltering Lantern to the door.

“You did that on purpose,” Adam hissed at Jack.

The older boy smirked and began climbing the ladder to the hay loft. Adam watched the little mechanical struggle to the yard then ran after both him and his master.

“Stay a moment,” he pleaded. “I believe I can be of service. The injury may not be as serious as we thought. If you could spare a little while longer.”

Sir Francis Walsingham was shaking his head, anxious to leave, but Doctor Dee assented and so back to the stables they went. Adam worked quickly. Sitting Lantern upon his own bench he was appalled at the sloppy workmanship of the older apprentice, but made no comment. Carefully, he put new steel pins into the knee joint and tapped out the remaining dents.

“You are very skilled,” the Doctor complimented. “Previously, in the barn, you excelled with Belladonna where I could not. You know your trade well – I foresee a prosperous future for you.”

Adam laughed. “Tell that to Henry!” he said indicating the boy who was now lying fast asleep across two sheep in the corner. “He’s the one who wants to be rich.”

“And you do not share that ambition?”

“I don’t want to leave Malmes-Wutton. I like it here. This is where they found me and this is where I belong. Lord Richard’s been more than kind – even lets me read the books in his library. The ones he didn’t have to sell, of course.”

The Doctor was impressed. “A scholar, in addition to your practical accomplishments.”

Again Adam laughed. “I just like to know things, that’s all.”

“Knowledge is all,” came the compelling reply.

Pausing in his work, the boy looked at the old man’s lined face. The pale hazel eyes were ageless, and wisdom more ancient than his august years was written across those brows. Almost without realising what he was saying, Adam asked, “Do you really dig up bodies and speak to the dead?”

The impertinent question did not irritate the Doctor in the least. “I use whatever means I can to further my understanding,” he said warmly. “I have studied necromancy, alchemy, I am a cabalist, hermeticist, mathematician and much more besides. I alone have cast the Queen’s horoscope without fear of losing my head, for it was at Her own bidding, you see – I luxuriate in the indulgence of Her Majesty.”

“Is She really as beautiful as talk would have Her?”

Doctor Dee’s features took on a solemn aspect and in a low, almost reverent voice said, “She is Gloriana. In the old world that is gone, She ruled us with honeyed words and a lion’s heart. Flattery deified Her then, but now She is indeed a Goddess. Though we ordinary folk endure our extended years more ably than before, hardly a mark of age blemishes Her countenance. Where we weather one year, a single day passes for Her. Yes, She is beautiful, but then what is beauty? The sea may be deemed a ravishing sight, and yet ships are lost and men drowned.”

At that moment, a stern voice called from the yard. Walsingham would wait no longer.

“I think that’s as much as can be done anyway,” Adam said. “I’ve strengthened the joint and fixed a few bits that Jack overlooked.” Covering the mechanisms, he helped Lantern from the bench and the copper secretary took a couple of hesitant steps.

Adam had proven better than his word for the leg was stronger than ever. The limp was gone completely and, as his confidence returned, Lantern gave a dance for joy and bowed repeatedly to the apprentice.

“We are grateful,” Doctor Dee announced. Then, giving the scrawny boy a long, appraising look, said, “This is not the end of our acquaintance, young Adam o’the Cogs. We are destined to encounter one another again. Perhaps you will even inspect my library at Mortlake; it is considered to be the greatest in all Englandia. I look forward to that day.”

Wrapping his dark red robe about him, he left the stables and Lantern went skipping after.

At the entrance, however, the mechanical paused. His round head swivelled about and the green eyes shone back at Adam, the gentle light flickering uncertainly. Retracing his steps he stood before him once more and opened a small door set into his side.

“What are you doing?” the boy asked, puzzled. “They’re waiting for you.”

Taking an empty bottle from the workbench, Lantern proceeded to syphon a small quantity of black ichor from his own internals and handed it to Adam with yet another low bow. It was the most precious thing he had to give and the only way of expressing his gratitude.

Deeply touched by the startling, unexpected gift, Adam was not sure what to say, but Lantern was already bustling from the barn.

In the yard, Walsingham, Doctor Dee and the groom were seated upon their horses when the secretary came pattering out. The astrologer hoisted the mechanical up behind him and they were ready.

Surveying the darkened manor of Wutton Old Place, Sir Francis commended himself upon the highly favourable outcome of his plan. The traitor had been dealt with, and in such an unimportant, benighted place that only minor ripples would ever reach the court. Confident that he had served his sovereign well that evening, and regretting only the loss of a most valuable steed, he spurred his inferior horse into action.

Emerging from the stables, Adam watched them depart. Along the road which led through the village, the four horses went galloping, merging with the black shapes of the night. Only the candle which still burned within Lantern’s hat disclosed their progress, but more than once the boy imagined he saw two circles of green light glow beneath it.

When even that receded into the distance and passed out of sight, and the only sounds to be heard were remote mechanical hoof falls, Adam wandered across to the piggery and sat upon the fence.

In the manor house a solitary light bobbed behind the windows as Lord Richard ascended to his bedchamber. He had observed the nobles’ departure and earnestly prayed to God Almighty that he might never have to deal with any from court again. A grim silence settled over the estate, broken only by a faint bellowing which echoed from the outlying woods.

“Even Old Scratch has been disturbed and upset,” he muttered dismally. “None of us can get any rest this evil night.” And he tramped to his room, a candle in one hand, a jug of ale in the other.

With his back against the pigsty, Adam listened to the distant trumpeting of the wild boar which terrorised the woodland. His mind was churning over everything that had happened. The horrendous events of the night were only just beginning to sink in. He had never encountered death before and it frightened him. In this uplifted world people aged much more slowly and only lost their lives through sickness or misadventure. This loathsome murder was the first death to have blighted Malmes-Wutton since before he was born.

Edwin Dritchly would never praise nor criticise his work any more and tears streaked down Adam’s face when he realised he would not hear that familiar “Hum hum” again. Bowing his fair head, the boy wept quietly.

Presently he became aware of a soft snuffling noise at his feet and, swivelling around on the railing, he saw that Suet had come toddling from the sty and was gazing up at him.

“Hello,” Adam said, wiping his eyes. “Is Old Scratch’s booming bothering you too?”

The piglet’s nose puffed in and out, and O Mistress Mine rose up composed of grunts and snorts.

A sad smile spread across Adam’s face at the sound of Master Dritchly’s favourite tune. Then, on impulse, he took from his pocket the phial of black ichor which Lantern had given to him and eyed Suet critically.

Next moment he was running back to the workshop with the little wooden piglet wriggling in his arms.