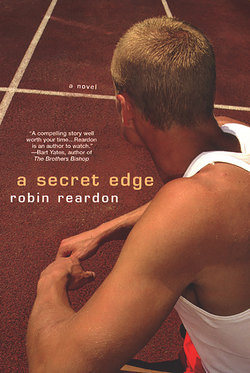

Читать книгу A Secret Edge - Robin Reardon - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 1 Dream a Little Dream

ОглавлениеIt’s like most of these dreams, when I’m lucky enough to have them. The other boy is a little taller than me, dark hair where I have blond, and deep brown eyes where mine are blue. His touch electrifies me, and my back arches in response to the kisses he plants on my neck, my shoulders, my belly.

And then I’m sitting up, alone.

I throw myself back down onto the bed, embarrassed, wanting to cry. Wanting to dream it again. The boy had been no more recognizable than any of the others. So I guess he was no more or less attainable.

I hate what happens when I’m determined to dream about girls. Which of course I should be doing if I’m trying to be like the other guys I know. Girls are what they dream about. But no matter how hard I try, the girl always turns out to be David Bowie. I barely know who David Bowie is! Just from a couple of tunes and that weird movie I saw at the retro theater last year. But there he is in my dreams, sharp bones of his face, lank hair, scrawny body, calling up feelings every bit as strong as the dark-eyed boys who haunt me.

I’m sixteen years old, for crying out loud! Shouldn’t I be having normal dreams by now? I don’t mind the sexiness of the dreams, but the sex of the people in them is making me crazy. I’m dying to ask someone about this, but there’s no one I can think of to talk to. Not Aunt Audrey, that’s for sure. I can just imagine her response.

“It’s called a wet dream, Jason.”

“Yes, Aunt Audrey, I know that. I’ve been having them for years. But why is it always boys in them?”

“Don’t worry about that. It will pass. It’s just a phase you’re going through. Did you take the sheets off the bed?”

But I do worry about it. I think it means I’m gay.

Really, you could ask Aunt Audrey anything, she’s so gentle, so even tempered. And there’s something about the fluffy style of her “prematurely” (she’s careful to stress that when she mentions it) gray hair that gives off a soft warmth.

But if I tell Aunt Audrey, there’s no way not to tell Uncle Steve as well. And then I’d have to be prepared for a no-nonsense answer. Matter-of-fact doesn’t come close to how he approaches life and everything in it. I don’t want a no-nonsense approach to this question. No-nonsense makes it seem like nothing is more important than anything else. Even me.

But that’s not fair. All right, they won’t let me have my own cell phone (“When you can afford to pay the bills yourself, young man…”), but I know they care for me. I mean, if they didn’t, would they have kept me? I was dumped on their doorstep at the ripe old age of two, after my parents died in the car wreck that didn’t do more than scrape my tender baby skin in a few unimportant places.

Aunt Audrey has told me that I’m like the child she and Uncle Steve couldn’t have. But we have an understanding, he and I. I don’t bring him anything that isn’t really important, good or bad, and he doesn’t make me feel silly for bringing something to him.

Aunt Audrey may be easier to talk to, but she can be tough as nails when she needs to be. Even a crisis wouldn’t faze her. I know she’s cool in a crisis, because the surgeons at the hospital want her more than any of the other nurses when they’re in the operating theater. But—I need more than her usual cool reaction, so I don’t bring this question to her.

So she wields a knife, in a way, where she works, and—unbeknownst to her—I wield one where I work as well. School.

Okay, wielding a knife is overstating it. I just carry the thing around. I’m probably giving the impression that my school is a dangerous place, which it isn’t. We don’t even have metal detectors, or I couldn’t carry it. But I decided a long time ago that I wasn’t going to run all the time, away from the bullies and the tough kids who think I’m easy prey just because I have this baby face and I’m not very tall. If they believed I was gay, it would be even worse.

Anyway, dream over, I massage myself into something resembling calm and roll away from the wet spot. And before I know I’m asleep again, the alarm goes off.

The day begins like any typical day, despite how important it will turn out to be. Despite the fact that it will change my life. Aunt Audrey has already left for the hospital and Uncle Steve is still in the shower by the time I’m dressed—his schedule at the vocational school where he teaches math is later than Aunt Audrey’s—so I grab something from the kitchen and gnaw on it while I’m dressing. I could catch the bus that picks up kids who live over a mile away from school—I’m a mile and a half—but unless it’s pouring rain, I walk. And I walk superfast, to keep my breathing in shape for my favorite “subject.” Track. It’s spring-training time. I don’t pretend I’m Olympic material. I just love it.

I love the long-distance run, when you feel like you’re about to die and if possible you’d hurry it up because you feel like crap, and then suddenly you reach this place where your mind and body are the same, no difference, no boundaries, and you feel like there are no boundaries for you anywhere. I also love the short dashes, the sharpness of my senses as I wait for the signal, the huge burst of energy that the signal releases, the feeling that, once I’m under way, no one can catch me. Most guys are much better at one or the other—distance or dash—and it’s true I’m faster on the dash. But I love all of it.

Most of all I think I love it because now, now that my knife and I have scared most of the goons away, I run because I want to. Not because they want to make me.

Today after school the trials for track intramurals start. One thing I’m competing in is the hundred-yard dash, but my real goal is to be anchorman for our relay team. Anchor is the last of four runners, always the fastest. So, yeah, I want to be picked for best.

My last class of the day is English Lit. We have this teacher who seems to think everyone should be able to write. But, you know, some people just don’t have it in them. Not everyone who can construct complete sentences is a writer, and many kids can’t even do that. I guess Mr. Williams is trying to improve this situation, and I wish him luck, but—really.

Take that kid who always sits halfway down the room beside the wall like he’s trying to avoid being noticed. If you sit at the front, you look too eager; at the back, you’re hiding and really begging the teacher to pick on you. So Robert Hubble sits halfway down. But he can’t bring himself to sit in the middle of the room. He has to hug the wall, like if he were put to it he’d know what was behind him.

Actually, he looks like the kind of guy who’d know what to do if he were up against it. He’s tall, heavy in a powerful way, with a face so homely it’s almost attractive. Not your typical A student. And he can’t write, that’s certain. I’ve heard some of his attempts. But he seems like an okay guy, just not someone I have much in common with.

I glance at Robert as Williams is giving us today’s in-class essay assignment: write a character sketch of Jesus. Robert’s jaw falls, and he fixes a kind of empty stare at Williams. I can imagine him saying to himself, “What? You want me to do what?”

I dig in. I love this stuff. I might be a writer when I finish college. Who knows?

I stop at my locker on the way to the trials to pick up books I’ll need for homework tonight. As I slam it shut, I’m greeted with the unpleasant grin of Jimmy Walsh.

Once upon a time, in a far-off land, I was pretty good friends with Jimmy Walsh. Most of the kids in class liked him. He had this really confident air about him, he was good in sports, and some of the girls thought he was cute.

He used to read over my shoulder to get my math answers in fifth grade; that’s how I first got to know him. At first I didn’t like that, but then one day he stood up for me when this other kid (whose name I’ve forgotten, which is fine with me) deliberately threw a softball right at me. It was between innings, and I’d just made it to home base and put our team ahead. The guy pitching for the other team was pissed because he’d thrown too late to put me out. The catcher threw the ball back to second base, where the batter was headed, and put him out, but I’d made it. There was this signal that went between the pitcher and the second baseman just as the teams were starting to exchange positions. I didn’t think anything of it until the ball came smacking into my ribs.

“Hey!” I heard through a fog of pain. “What d’you think you’re doin’?” It was Jimmy’s voice. I turned a little, saw him throw his hat on the ground, and then he launched himself bodily into the pitcher. The coach broke it up pretty quickly and wasn’t any too pleased with either of them, but he’d seen me get hit so he knew what it was about.

I had no objection to letting Jimmy cheat off my math assignments after that. And we were friends, sort of—considering that we’re pretty different people—for a couple of years before it started to cool off. He used to come over to my house for dinner and stuff, and I was at his sometimes. His parents and my aunt and uncle never made friends in any particular way, probably because they didn’t have even as much in common as Jimmy and I did.

The beginning of the end was when Dane Caldwell moved into our school district. Dane had to make a splash right away, I guess, because it didn’t take him long to start looking for people to pick on. You know the type? It’s like he’s got to prove he’s a man by pushing real hard at anyone or anything that doesn’t measure up to some masculine standard in his head. I guess I didn’t measure up, because it wasn’t long before he started pushing at me.

I’ll never forget the day he turned Jimmy against me for real. I was fourteen and starting to look good as a runner. Starting to be competition for Jimmy, actually, and I’d just proven it by beating him in a race during phys ed. And Dane was smart. He didn’t taunt me. He taunted Jimmy.

“Walsh, you gonna let that sissy boy beat you like that?”

There was a little more exchange between them that I don’t remember now, and nothing happened right away. But on my way home from school that day, they followed me. Both of them. If memory serves, I put up a pretty good fight; I’d been in a few scuffles in years gone by, and maybe I’d never be a fighter, but I was no chicken, either. But finally Dane got my arms behind me and held me.

“Give it to him, Jimmy!” he shouted.

I looked right at Jimmy’s eyes, panting through gritted teeth, and said, “Don’t let him do this to you. Don’t let him turn you into a bully.”

He plunged his fist into my stomach. And again. And I’m not sure what happened after that, except that some lady came out of nowhere and yelled at them. They ran, and she half carried me down the street and into her house.

“Who were those boys?” she demanded. “What are their names?”

I was in a hell of a lot of pain at this point, but I managed to say, “Never saw them before.” Even today I’m not sure why I lied. Some misplaced loyalty to Jimmy, maybe. Anyway, she made me give her my home phone number, and Aunt Audrey came to get me.

And the demands for information started all over. “Jason, I insist you tell me! Those boys have to be punished.”

By now there was no doubt in my mind that I had to keep quiet. I mean, think of the terror campaign they’d have gone on if I’d ratted! Thank God Uncle Steve reacted differently; I think he understood.

“Audrey, if the boy doesn’t know them, he doesn’t know them.” Then to me, “You okay, son? How bad are you hurt?”

“I’ll be all right. Really. It hurt a lot before, but it’s better.” And it was better, sort of; but what hurt the most was knowing that Jimmy had let Dane make his dark side too powerful to be my friend anymore, probably forever.

The next day at school it was like Jimmy had never stood up for me for anything. From then on, every time I saw him or Dane, and especially if they were together—which was the case more and more—they’d make these smirky faces. Pretty soon they started calling me sissy and wuss, and they’d do things like push my tray off the table in the cafeteria. The school year was almost up, and I knew I wouldn’t have either of them in many of my classes next year, but I was starting to get a little worried. It was bad enough when I was little, getting picked on and slugged occasionally. But a ten-year-old can hurt you only so bad. When the bully is fifteen, it raises the stakes. It wasn’t out of the question for me to get really hurt. And I was beginning to feel afraid, which of course is like waving raw steak under the nose of a hungry dog.

That’s when I decided to arm myself. I searched eBay until I found someone willing to let me pay for a switchblade with a bank check. Now it goes with me almost everywhere. Not many people know about it, but I do. And that’s what counts.

The look on Jimmy’s face right now as we stand here by my locker, like he thinks I’m the scum of the earth, makes me glad that knife is with me. It gives me the courage to look blankly at him, like I don’t give a shit what he thinks of me, as I give my locker combo a few turns. I’m about to walk away when he decides he’ll have to speak first.

“Running today, are ya?”

I don’t answer, so he has to try again.

“Think you’ll beat me? Think again.”

I turn my back on him and walk—saunter—away. He’s in the competition for short dashes. Not relays. But I’m trying out for short dash as well, and I’ll beat him if I can. He’s fast, but his performance is inconsistent.

On my warm-up jog around the track, I pass by the high jump. There’s only one guy there, practicing, someone I don’t recognize. At first I think he’s black, but as I get closer I see he’s more likely from India or something. His hair has a beautiful gloss to it, and his face—intense with concentration—transfixes me. It’s a big school, over three hundred in my year alone, and there are lots of guys in my class year I don’t know. But I’m surprised I’ve never noticed this fellow before.

I slow to a walk and watch as he starts his run. He’s so graceful, it’s almost like slo-mo. There’s no doubt he knows just where he wants to take off from, and there’s no doubt he does it. And then he’s soaring. I’m motionless now, except for my eyes, which are following him in this incredible flight. His body twists slowly, gently, and when he lands, every part of him is where it should be.

I’m still there, staring, when he walks around from behind the jump. He sees me. He just stands there, poised and perfect, staring back at me. It’s like he wants me to admire him. Maybe he does.

I shake myself out a little and jog back to where Coach Everett is gathering the runners. But I can’t shake the face of the high jumper. The arched black eyebrows, the curve of the full lips—these stay with me.

There will be only one relay team from our school in the intramural competitions, so only four of us will be picked as finalists. But there are about seventeen guys waiting to compete, so we do a few elimination heats.

We’re down to eight guys in no time, which means that we’ll race four and four against each other. Then Coach will mix us up and we’ll do it again to get the final team. In relay, it isn’t just speed that counts. If you drop the baton in the handoff—well, it’s pretty much over. You still pick it up and run, but just so you can say you did.

For the first of these final heats, Coach puts me in the starting position. Not what I want, but it’s the second fastest, and you have to get off to a good start, so there’s some glory in it. We win.

Mixed up again, I’m anchor this time, but we don’t have the inside track. This means we start farther ahead, but it’s harder on the curves anyway. Maybe it’s just a psychological thing, but it seems real. Those of us in nonstart positions jog off at angles toward our posts to wait for the baton.

Since I’m anchor, I see the whole race as it happens. Denny Shriver is our start, and he gets a really good launch, exploding from the line like a champagne cork. He’s handing his baton off to Paul Roche ahead of the other team’s handoff, so we’re in great shape. I almost don’t want this, because I shine better if we’re a little behind, but I’d rather have a sure win than risk wishing for a slow runner.

For some reason Paul is in some kind of frenzy and he runs like I’ve never seen him. He gets to Norm Landers way ahead of the other team. Paul is about to hand off just as I’m starting to dance a little so that I’ll be ready to pace with Norm when he approaches me, and suddenly the baton is on the ground. I can’t tell whose fault it is. It doesn’t even matter. What matters now is how quickly Norm can pick it up and how fast I can run. Our lead is gone.

I don’t even look at the other team’s runner. I don’t allow myself. Right now the baton is everything. In a minute, the finish line will be everything. Norm’s pumping toward me, grimacing with effort. And then all I can see is that baton.

I don’t even know when my feet start moving, but by the time Norm reaches me we’re like two parts of the same machine, two pistons working in tandem, and the engine is smooth. Our hands are together on the baton only as long as it takes for me to relieve him of it, and I’m off.

It’s all mine now. It’s all my race. Denny, Paul, Norm—they’ve done their part, but from here on it’s up to me. Somewhere on the edge of my vision I can see another boy, running, ahead of me. I can just make out the motion of his arms flying forward and back, the whipping motion of his jersey. But I’m not looking at him. I’m looking at the finish line.

There’s no thought. My concentration moves my arms, my arms move my legs, and I’m flying.

A split second before I cross the line, I pass the other guy. A split second. But it’s enough. It’s fantastic.

I hold my arms up as I run forward, slowing down, opening my mouth wide to get as much air into my lungs as possible. I can hear cheering behind me, and I turn, a grin on my face.

And then I see him again. The high jumper. He’s in the bleachers this time, standing, watching me, his face expressionless. I shake my hands in the air once, still clutching the baton, looking right at him. I want to shout, “Yes!” But his look has silenced almost everything. I can’t hear cheering now. But I can hear myself breathing. And if he even whispers, I’m sure I’ll hear him.

And then he smiles. Suddenly I can hear clapping again. I do shout now. That “Yes!” I’d wanted to. I do. And it feels great.

He turns and moves away. I stand there for a second, grinning after him, and then lope back to my team.

Paul is pretty upset; he feels it was his fault the baton dropped. It seems the coach agrees with him, or maybe there’s some other reason, but Coach doesn’t put him on the final team. Paul’s performance is a little like Jimmy Walsh’s; some days he does great, some days he doesn’t. But I like Paul. Too bad, though; this isn’t a friendship team, and we want to win. So the final team is me, Denny, Norm, and the anchor from the other team, Rich Turner. But I’ll anchor ours. I’m soaring now, as high as that fellow over the high jump.

Speaking of Jimmy Walsh, I know I’m up against him in less than fifteen minutes, when we do short dashes. A number of us from the relay competition will try for dashes too, so Coach gives us a few minutes’ rest. I look at the tryout sheet posted on the side of the bleacher: high jump next.

Everyone is moving that way, so I fall in. I’m fully expecting to see that Indian fellow again, and I’m expecting he will outshine everyone else there.

I’m not wrong. He’s fifth in a group of nine contestants. Coach Everett calls out something unintelligible, stumbling over the unfamiliar syllables of my Indian’s name. But I know it’s going to be him. And he does, in fact, soar every bit as gloriously as he’d done before the relays. It’s the sort of thing that’s so studied, and yet so effortless, that you know it will be the same every time. Until it gets even better.

It doesn’t get better today, but it doesn’t need to. He beats everyone else hands down. But we get to send two jumpers, so Dane Caldwell will also represent us. Remember Dane? The one who turned Jimmy into my enemy? He does okay, I have to admit grudgingly.

I watch to see who goes up to congratulate the Indian. I’m not the most popular kid in school, but a lot of guys clapped my back after that relay. But no one moves toward the high jumper. So I do. I reach out my hand. He looks at me a second and then takes it. His eyes are such a deep color I feel like I could fall into them.

“Jason Peele,” I tell him, trying not to sound as breathless as I feel. “You were fantastic.”

“Thank you. Nagaraju Burugapalli,” he says in the most lilting, undulating tones. Seeing my blank stare, he adds, “You Americans usually find it easier to call me Raj.”

I hear Coach shouting for the dash contestants, so I just say, “Anyway, great job.” And I turn and jog back to the starting line.

Again we have to go through a few elimination runs. I’m sort of watching how Jimmy is doing and sort of watching to see where Raj has gone. Jimmy is doing well; Raj is nowhere in sight. I guess he decided not to stay and watch the other trials, and I’m disappointed. It means he didn’t want to stay and watch me.

As luck would have it, I’m up against Jimmy in the final heat. He grimaces at me before falling into his starting position, and I swear he growls, but I could be making that up. I’ve done well so far, or I wouldn’t be in this last heat, but there’s no denying I’m tired. I have to call on all my concentration not to let Jimmy’s ill will affect me. So I try to imagine something great at the finish line that I want to beat him out of. But what?

The signal goes before I come up with something, but I’m ready to run. So’s Jimmy. We’re neck-and-neck for a good seventy-five out of the one hundred yards. I can hear him breathing through clenched teeth, occasionally grunting with strain.

And then I see my goal. Or, rather, I don’t. It’s a mirage, I’m sure of it, and yet there’s Raj standing just past the finish line, his deep eyes full on me. I know it’s my mind doing this, he’s not really there, but I sure don’t want Jimmy to get there first.

He doesn’t. Again, it’s a split-second-or-two win, but it’s a win. But there’s something dark in it; I don’t feel like shaking my hands in the air and shouting, so I just run forward a ways and bend over, hands on knees, panting. That’s done it; I’m in the dashes.

Jimmy’s time is still good enough to qualify him, so he’s on the final team. But I can tell he’s pissed that I beat him. He’s punching at nothing and scowling as he gulps for air; it’s a funny picture, but I’m not in the mood to laugh, and I don’t have the breath.

I decide to ignore him. I turn and walk toward where the other runners are standing. Once I’m there, someone in the bleachers catches my eye. But this time it’s not Raj. This time it’s Robert Hubble, the guy from English Lit. I’m standing there, hands on hips, puzzling over this, when he grins and waves. So I shrug and wave too. Guess he just wanted to watch the trials and congratulate someone, and I was looking at him. That’s cool.

There are a few more trials—shot put, running long jump, things like that—but I decide not to hang around. I just want to hit the showers and go home, where I can find something sugary to eat before Aunt Audrey can stop me.

There are a few runners in the showers, but a lot of guys are still trying out for other events. I don’t see Raj; he must have left already. But I don’t see Jimmy or Dane either, and I didn’t think they were competing for anything else. Never mind.

The main gate to the athletic field points you back toward the school, but there’s a side gate that leads to a small wooded area next to the road that makes for a shorter walk home. I’m ready for a shorter walk. I work the latch, a rusty, cantankerous old thing, until it gives. I shut it behind me, test it, and turn to walk toward the road.

Suddenly there are two other guys there: must have been behind trees or something. It’s Jimmy and Dane, of course. I freeze. They’re still in track getup, and I’m back in jeans and my leather jacket, not to mention the heavy backpack. No chance of outrunning them, and forget opening that old gate again. Seems like old times.

“So, you think you’re pretty hot stuff, eh?” is Jimmy’s snarling contribution.

There’s no good response, so I don’t try. They begin to separate a little, each of them slightly to one side of me.

Dane goes next. “It would be such a shame if you couldn’t run, wouldn’t it? Like if you had a broken leg or something.”

Slowly I shift my pack off my shoulder, but before I set it down I reach into an outer pocket and grab my folded switchblade. I’ve never had to use it on anything that was alive, but it seems like this might be the time to consider it. Or at least make it look like I would. I pop it open.

They both see it and stop moving, their eyes glued on it. We’re standing like that, as though we’re waiting for some slow photographer to capture the image, when I hear running feet on my right. All three heads turn.

It’s Robert Hubble.

He stops running and sort of lumbers forward. He looks at me, at my knife, and then at Dane, who’s nearest him.

“What’s going on?” he asks. It’s not entirely clear what his own intentions might be.

Jimmy decides to try and co-opt him. Hands on hips, doing his best to look confident, he says, “We’re just going to teach this little faggot here a lesson.”

Faggot?

Robert stares at him for another few seconds and then moves over toward me, facing the others.

“Seems to me,” he says in a drawl that challenges contradiction, “there’s not a lot you jokers could teach him. Why don’t you try teaching me?”

Robert faces off against Dane, and I turn my full attention to Jimmy, knife still at the ready. But they decide they aren’t up for this kind of fight, so they back away several paces and then turn and run toward the road.

When I’m sure they’re gone, I refold the knife and tuck it into a pocket, trying to put Jimmy’s accusation out of my mind and trying to keep my hand from shaking. That was a close one.

“You, my friend,” I say to Robert, hand up for a high five, which he gives me, “are a lifesaver! Where the hell did you come from?”

“I was looking for you. After the trials. But you didn’t come out the front door, so I thought maybe you’d gone the other way. And I saw you guys down here. Didn’t look friendly, so I just thought I’d see what was going on.”

“Looking for me? But why?”

Robert makes a few grimaces, seemingly not sure where to start, and finally leans his shoulder against the fence, hands in his pockets.

“Well, you always seem—it always seems like you understand that stuff. In Williams’s class. You always know what the book is really about, not just what the words say—you know. And I’m lucky if I even get all the words. And forget writing about it. So—I dunno, I was hoping maybe I could talk you into giving me a few pointers. I can’t afford to fail another class. I already got kept back last year, and my dad’ll kill me. Plus, you know, it’s embarrassing.”

I’m thinking, uncharitably, that’s probably the most words the fellow has strung together in one speech in his life. He’s looking sheepishly down at his shoes now. I can’t help grinning.

“And did you set those two goons on me just so you could rescue me and I’d owe you?”

He looks horrified. “What? No, I—no!”

I chuckle at the expression on his face. “Look, I’m only kidding. When do we start?”

We start that night after dinner. Aunt Audrey has this policy that I don’t go anywhere with friends she’s never met, so we decide it’s easier if he comes to my house. Plus, he says his little brother is a bit of a pain. So when he shows up, we head for my room, and I think about what music to play. Call me weird, but it helps me to think if I play something really old like Bach or Mozart. Aunt Audrey says she got me started, putting that stuff on when I was little whenever I was doing something like drawing or practicing reading, that sort of thing. I guess it stuck.

I start the CD player, put on a disk, and sit on the floor with my back to the bed.

“What’s that you’re playing?” Robert is halfway across the room before I answer.

“Bach.”

“Well, no,” he says, picking up the jewel case and scowling at it. “Says here it’s somebody called Brandenburg.”

It’s a good thing I’m on the floor already, or I’d have hurt myself falling. I can barely speak for laughing. Robert just stares at me, not getting what’s so funny, and I’m wiping tears off my face and trying to explain.

“That’s the name of the guy who asked Bach to write the concertos,” I manage finally. “Some nobleman of Brandenburg, in Germany. He commissioned them, and they were named for him. Johann Sebastian Bach wrote them. Look again.”

I decide this is our first lesson. Robert had just seen the large text and stopped looking. He scowls now at the cover, and soon his face relaxes and goes a little red. Maybe he wouldn’t be embarrassed if I hadn’t laughed at him, but—really.

“Hey,” I call to him, “bring it here. Sit.” I pat the floor beside me.

Together we go over the labeling, and he agrees that his misinterpretation is a lot like how he reads our English Lit assignments. He doesn’t take things in, just reads enough to get a superficial understanding of something.

Next I reach for my copy of A Handful of Dust, our current assignment. I hand it to Robert and ask him to read the opening quote and first paragraph.

“Okay,” I say when he’s finished, “now try and tell me, in your own words, what that first paragraph says, and where you think it might lead. Pretend you’re telling me the story.”

He looks at it, glaring. I can practically smell the wood burning, he’s thinking so hard. Finally he says, “Well, I think it might be saying—”

“No, wait. Don’t tell me what you think it says. See if you can construct your own story and have it say the same thing, but in different words, and then go on with what might happen next.” He’s silent so long that I ask, “Would it help to write something down?”

“Are you sure this will help?”

“It’s not something you’re going to do a lot of, but it’s a test of how well you’re internalizing what you read. If you can’t do that, you can’t see between the lines. And if you can’t do that, then the only point of reading fiction is momentary entertainment.”

While he’s digging through his bag for pen and paper, I ask, “Robert, was there a particular reason you decided to take English Lit? It’s an elective, after all.”

“Sure there was. I can’t do advanced math, that’s certain. I hate Civics, and I’m not smart enough for French. I figured, y’know, I can read.” He shrugs. Obviously, he didn’t know what he was getting himself into.

He sits back down next to me. “What did you write today? About Jesus?”

“The character sketch. I enjoyed that. I took the position that Jesus of Nazareth was a very gifted and spiritual person who was convinced by desperate people around him that he was the fulfillment of this biblical prophecy. And because he was convinced of it, he did everything he could think of to make it work, but there were too many people who had differing ideas of what that would mean. He wanted nothing more than for everyone to understand God the way he did. But he couldn’t quite bring himself to bend his image of God to fit what was expected of him, and that was his undoing.”

About ten seconds of silence later, Robert says, “You put all that into one paper?”

“I write fast.”

I’m tempted to ask him what he wrote. But now that I’ve told him about my paper, I’m not sure that’s a good idea. So we go back to the first paragraph of A Handful of Dust.

He makes some progress, but pretty soon that wears thin, so I decide we should start a character sketch he can finish on his own. At first he wants to do his favorite football player.

“You can do that if you think you know enough about him personally. Mr. Williams today made an assumption we all had enough information about Jesus to do the assignment.”

“What would I have to know?”

“What factors do you think went into his decision to play football? Did he have a father who was physically handicapped and this is like a gift for him, or a father who always made him feel like a loser and this is a way to prove himself? Did he have a sister who made him feel like he could do anything he really wanted to do? Or is he just some dumb lunk who can’t do anything else? Does he have an interest outside of football that inspires him or has taught him lessons he brings to the game? Does he—”

“Okay, okay. Maybe I don’t know enough. So who then?”

“Santa Claus.” I don’t know where this comes from. It isn’t even Christmas season, and I haven’t believed in Santa since I was four. An early skeptic, if you will. But I can smell cookies baking, and Aunt Audrey used to leave cookies out on Christmas Eve.

“Santa Claus?” he echoes.

“Sure. Why not? I mean, maybe you don’t know who his father is either, like you don’t with the football player’s family, but in this case you could make it up. In a way, this is a double exercise. First you have to construct the person, and then you have to put together the reasons why he ended up in that career.”

He’s still looking blankly at me.

“Tell you what. We’ll work together to get some background down, and then you can take that with you and work on it for a character sketch. If you get stumped, we’ll work on that part together as well. Okay?”

I can tell it isn’t, really, but he’s asked for help, and it seems he’s determined to take it.

Just before we’re done, Aunt Audrey knocks on the door and opens it.

“Boys, I have some chocolate chip cookies if you’d like some. Keep up your energy. In the kitchen, whenever you’re ready.”

She disappears again. I really could have done a lot worse than Aunt Audrey.

Robert gets this determined look on his face, like he’s trying really hard not to be distracted by the thought of those cookies. He leans over the notebook and scowls. While he’s scribbling away, my mind goes back to one of those times when I’d been practicing drawing and Aunt Audrey was playing one of these old classics. I was using my brand-new, gorgeous set of colored pencils. That set was huge; not a color in the world was missing from it. I loved the feel of the pencils, the way they moved over paper, the way you could use water to make the color intensity change. I was never much good at the drawing itself, but I really got into the colors.

We’d bought that set of pencils together. I was just starting second grade, and after a few sessions in Art it was obvious the pencils in class were lousy. So the teacher said we could bring in our own if we wanted to. I told my aunt and uncle this, and Uncle Steve asked if I wanted my own set.

“I dunno. There’s pencils there. I can use those.”

Aunt Audrey went next. “But are there enough to go around? And do you enjoy using them, or are they all chewed and broken?”

It was like she could see them herself, like she’d gone to the class and had seen how grungy they were. I just shrugged, but that weekend she took me to an art store. I’d never known places like that existed. Man, there was nothing they didn’t have! I was running around looking at everything, but especially the paints and pencils, anything with color.

If there was one thing Uncle Steve had made me understand, it was that we weren’t poor, but we didn’t have money to throw around. So when it came time to decide on some pencils, I picked up the smaller set. Aunt Audrey grinned at me, tousled my hair, and put it back. She handed me the larger set. The huge set. The one with more colors than I had names for.

“Now, young man, these are pencils, and you’ll be using them in water sometimes, and they’ll get dull very quickly. Let’s find you a good sharpener you can carry.”

And again, going for cheap, I picked up a black plastic one. But Aunt Audrey went to find a sales clerk.

“I’m considering pencil sharpeners, but I want to make sure of the quality. Is there a pencil I can test with?”

We stood there with our test pencil and tried every sharpener we could see. And the one that worked best was not the plastic one, and it was not the cheapest one. It was metal with a really cool gold matte finish.

“We’ll take this one, and these pencils. And while we’re at it, we’d like a tablet of your best drawing paper.”

I took them to school the very next day, really excited about all my new stuff. During Art, I was working away at a long wooden table with my beautiful new pencils, sharpening them from time to time with the gold matte sharpener, and really getting into the drawing. The pencils made it easy, and the paper was the best, and the sharpener was there whenever I needed it.

I was sitting beside a girl named Kristi. Everyone knew her parents were really rich. She was nice, didn’t lord it over anyone, but they had lots more money than my family. So there we were, working away, and Kristi kept clicking her tongue like she was disgusted about something. At one point she sat back hard and threw her dark green pencil onto the table. I watched it clatter across the wood.

She looked at me, I looked at her, and then she looked at my pencils. Then we both looked at hers. It wasn’t a very big set, and it looked like there were some colors missing. Most of the pencils that were there were broken and chewed, just like the ones Aunt Audrey hadn’t wanted me to have to use.

I offered her one of my two kinds of dark green, and she ran it across her paper. Then she said, “No wonder my mom said I could have these old pencils. The color part is all crumbly!”

You know, I don’t think I ever told Aunt Audrey about Kristi’s pencils. I think I’ll have to do that. I think I’ll have to let her know that I realize she’s always treated me more like a son than a nephew. And that if I’m like that son she and Uncle Steve couldn’t have, then she’s like the mother I can’t really remember.

Suddenly Robert throws his own pen down in disgust. He’s ready to get up right now, but I want to see what he’s written.

“Hang on,” I say as I lay a hand on his leg to stop him getting up. He reacts by trying to pull away from me while he’s in the process of lifting from the floor, and he falls over heavily.

“You all right?” I ask, trying not to laugh at him again.

“Yeah.” He sits up, rubbing an elbow. “I think I have enough, you know. I’ll take this with me.” He nods toward his notebook, which we’ve been writing in.

I can sense there’s something else going on, but I don’t know what. “That’s fine. Are you sure you’re okay?”

He slides over to lean against the wall, a few feet from me. “Yeah. I just—well, I guess I just need to be sure of something.”

He stops. I wait.

I give up. “Like what?”

“Those guys today. Jimmy and Dane. Jimmy called you—he called you a faggot.”

I try not to let my cringe show. “So? He calls everyone a faggot. He thinks it’s this big insult.” I stop, hoping that will do it, but—no. “Are you asking me if I’m gay?” He says nothing, but the look on his face tells me that’s it. “So when I touched you just now, that made you nervous, right?”

Maybe a year ago I would have laughed as hard as I’d laughed at the Brandenburg error. Maybe, if I hadn’t been dreaming those dreams.

He shrugs. “Well, I mean—sure, he probably says that to a lot of guys. But you…I’ve heard some of the girls say how cute you are. Maybe that kind of boy thinks you’re cute too.”

On one hand, I like this. I do have a nice build, even if it’s not supermuscled; I’m a runner, not a football player. And I spend as much time looking in the mirror as anyone else. So it’s nice to know that others like what they see. But—that kind of boy, eh? “That kind” might be me.

But this isn’t something I want to deal with here. I attack from the side. “Do you have a girlfriend?”

Now he looks scared, and I do laugh. I can’t help it. “Robert, will you chill? I was going to suggest that we double-date this weekend. I’m going to ask Rebecca Travers out, and in the past she’s had an easier time getting permission if it’s not just the two of us. What do you say?” I hadn’t really been planning to ask her out this weekend, but I may as well.

He’s grinning a little sheepishly now, still rubbing his elbow absentmindedly. “I, uh, I—honestly, Jason, I’ve never asked a girl out.”

If I weren’t afraid of offending him, I’d try to turn the tables and ask if maybe I’m the one who should be afraid he’s gay. At least I’ve been dating for a year, even if it was just for show.

I collect the stuff we’ve strewn all over the floor as I tell him, “That, my friend, will be another lesson, then. Tomorrow after school, you and I will go to the mall, and I’ll teach you how to talk to girls.”

I stand and hold my hand out. He grins and then takes it, and I haul him to his feet. Or at least I provide a balance point; he’s too big for me to haul anyplace. And then we go massacre half a batch of cookies.

That night, as I’m trying to fall asleep, I’m haunted by my deceit, by what I’ve done to mislead Robert. To mislead everyone. Even me.

It’s true that I’m not the least intimidated talking to girls. I feel like I’ve got nothing to lose. But most of my dates have been with Rebecca, someone I’ve known all my life, someone who lives in the next block from me. In fact, I’d started asking her out almost by default. And partly out of a sense of—I don’t know, maybe expectations. Other people’s expectations. I mean, wasn’t I supposed to want to ask girls out? Wasn’t I supposed to want to touch them and kiss them and have them touch me and kiss me?

Rebecca and I have been kissing since we were six, and although it’s true the kisses have, well, matured, they haven’t led to much else, and so far I haven’t been tempted to get them to. I was a little surprised, actually, the first time she opened her mouth when I was kissing her. After all, I was just practicing; wasn’t she? But then I decided this was practice too. If I was expected to do this, I’d better learn how. But it felt wrong somehow. I don’t mean like we were doing it wrong; how would I know that? But I knew it wasn’t what I wanted. What I want. What I want is something I can let myself have only in my dreams.

I shake my head to clear it; those dreams are scaring me. In the dreams, I’m not in control. Because then, when I can’t stop myself, that’s when it’s a boy I want touching me. A boy I want kissing me.

But that isn’t an option!

Is it?

What really scares me is that it might have to be Rebecca for me, or someone like her, which is to say someone female. I guess when I asked her out the first time, I was thinking, you know, believe it and you will see.

And I tried. I tried really hard. I started to pay more attention, watching TV or at the movies, when a man and a woman would kiss or more. When some girl in a song would gush about some boy or some boy would wail if some girl wouldn’t notice him. I paid attention to the way kids at school would talk. Even guys who don’t admit to being afraid of anything can’t hide when they aren’t really sure a girl will go out with them. Heck, if the girl will even talk to them!

I never felt that fear. Partly it’s because there was never any girl who made me want her. So I never worried about whether a girl would go out with me—at least, not in terms of having anything really personal at stake. And I also never felt those butterflies you hear so much about. You know the kind? When you think of the person you want to be with, and something fluttery happens inside.

And since it was so obvious everyone else did have these feelings, it started to make me feel isolated. Separate. Like not only was there something wrong with me, but also I couldn’t join in. I wasn’t part of the club. So I started asking out Rebecca, because it was easy. Because I didn’t want anyone else any more than I wanted her. And despite her parents’ concerns, I’ve never wanted to do anything they wouldn’t approve of. Caressing shoulders and even the roundness of her backside doesn’t seem to count for much when you consider the other treasures I’m supposed to have intentions about.

My mind drifts kind of automatically from what I don’t care about when I’m with Rebecca to something I used to love when I was little. When I spent as much time as I could with Darin, one street in the other direction from Rebecca’s house. Darin, who used to hide with me in his mother’s walk-in closet in the dark, shining flashlights onto each other’s naked groins. Darin, who got really brave one day and reached out a hand and touched me for real. Just thinking of that now sends these jolts of something through me, makes me breathe oddly.

It didn’t end there, either. Well, I mean, we didn’t do much, you know? We were kids. Sometimes we’d shut the door to his room when his mom was someplace, maybe out sunbathing in the backyard, and we’d lie on the bed and hold each other’s dicks. We’d press them together and giggle wildly.

I still remember the time he kissed me. It was just before his family moved away, when we knew we probably wouldn’t see each other anymore. We were nine. And we weren’t even doing anything. We were fully dressed, sitting on the floor in my room. It was August, and hot, and if we’d been “normal” boys we would have been outside playing tag or ball or something.

Hell, we were normal! It’s just that…It’s just that when he left that day, I knew he’d be gone. Sure, there was e-mail, but what’s that compared to having someone touch you where no one else does? To feeling about someone the way you never feel about anyone else?

I was looking at his face, trying not to cry. He reached out and touched my shoulder, caressed it a little, and then pulled me toward him.

His lips were so soft. And it felt so right. So fucking right.

Darin never liked Rebecca.

I toy with the idea of trying to dream about girls tonight, but I’m not in the mood for David Bowie. Finally I begin to drift off.

And then I’m having one of those dreams again. Only this time I know who the other boy is. This time, it’s Raj.

We don’t actually do anything in the dream. He’s standing at a distance, and he’s looking at me. There’s something about his eyes that makes me believe he would come to me if he could. It’s like he’s begging me to come to him. I try, but he never seems any closer. And there’s this feeling I get. It’s—I guess it’s a longing, more than anything else. I want to know if his skin feels different, it’s such a different color. I want to touch his arm, his shoulder, his hair, his face, his eyebrows. I’m breathing shallow breaths, faster and faster, and then—well, the usual. And it’s over.

I’m almost awake, but even though I’m still asleep I know I don’t want to wake up. I want to stay in the dream, where it seems right to feel this way about Raj, where no one is going to call me a faggot. So I struggle to stay under. I imagine touching his face again, but it seems even further away than before. I reach for his hand, but there’s nothing to grasp.

When I finally have to admit I’m awake, I’m furious. I couldn’t hang on to the dream, the feeling, and now I’m back where I have to let go of it. I’m half sitting up, pounding on my pillow.

“Jason?”

It’s Aunt Audrey, with the door open just a crack. I can’t speak. She comes in farther.

“Jason, are you all right? Have you had a nightmare?”

She sits down on the side of the bed. I wrap my arms tight around my pillow and bend my head over it, and Aunt Audrey strokes my hair. I want to tell her. This is important now. This is my life.

But all I say is, “I’m okay.”

“Are you sure?”

“It’s all right,” I lie.

And I hate myself for doing it.