Читать книгу Okinawa: A People and Their Gods - Robinson - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

SOME

BASIC CHARACTERISTICS

OF OKINAWA RELIGION

KAMI

From time immemorial the people of Okinawa seem to have believed in kami; it is a basic expression of their ancient folk religion. Kami is an animistic concept that all things living and dead possess a spirit; they may dwell, therefore, in all things animate or inanimate. As superhuman forces they possess the power to either help or hinder human endeaver. There are many kami, each independent from the other; it is necessary, therefore, to be in bad grace with only one kami to experience unfortunate consequences. Kami are deities, but the line between man and kami is as vague as the concept of kami itself. Nevertheless, since kami are seen as the source of divine intervention in human life, they function as gods for the believer.

Kami act in various ways: they supervise, influence, alter, or inform. They may also be organized in categories and arranged according to rank. According to one writer1 the heaven or natural phenomena kami is the highest. This is the kami who is said to have ordered two sibling-kami to create Kudaka Shima and populate the island. This kami is not to be confused with the Judeo/Christian God of Creation. Next in rank are the place or location kami. These are the kami of the well, pigpen, hearth, or paddy. Third in rank are the occupational or status kami. It is believed that every person has a kami that determines his spiritual status. Kami-persons (kaminchu) are thought to possess the highest spiritual status because of the kami that has possessed them. Status kami (saa) can be neither acquired nor rejected. One's status, it is believed, may be determined by a yuta or a fortuneteller; but since most religious offices are inherited, this tends to be determined by birth.

Ranking fourth, but by no means unimportant, are the ancestral kami (futuki). The last category is that of the kami person (kaminchu) who, despite human responsibilities (by some as a wife and mother), assumes a semi-devine status when she dons the white kimono and functions as a priestess. Both priestesses and yuta are commonly considered to be kami persons, although there is some question concerning the latter.

Since kami may be present in all things, their number is almost without end. Among the most influential kami in every day life are the hearth/fire kami (fii nu kang/kami); ancestral kami (futuki); life sustaining kami (mabui); remote ancestor kami (chiji), whom one serves and who offer guidance; ghosts (majimung); and a male spirit who lives in the Indian banyan reet (kijimunaa). In addition to these there is thought to be a nonpoisonous snake called "akamataa," who is said to possess the power to transform himself into a handsome young man with the power to seduce women. Those who fall prey to his charms are said to give birth to snakes. At least one shrine has been built in celebration of his defeat, the Kannondo Buddhist temple, at Yabu Village; this temple was originally built about 400 years ago.

AUTHORITY FOR KAMI FAITH

In traditional Okinawan thought there are two sources of knowledge: empirical, which is available to everyone; and supernatural revelation, which is limited to kami-persons. Kami-persons are instructed through hearing or dreaming, while being bodily possessed (completely or partially), or during a waking vision at which time the kaminchu is in full possession of her senses. In the latter experience the individual is a spectator or participant in something which he both hears and sees. Since this instruction is revelatory in nature, formal training is rejected as being not necessary; actually, training for the religious office is acquired through association with other priestess and yuta are considered to be divinely conferred. This is balanced in the thinking of the ordinary person by consultation with several kaminchu and the acceptance of the most reasonable opinion.

FEMALE ORIENTATION

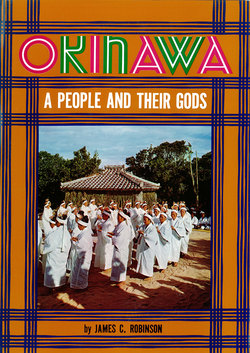

Women command the chief positions in religious leadership; their relationship to ancient practice and belief can be traced to the mythological creation story in which they received an early identification with religion. Men have never been associated with religious authority; when they have participated in religious rites it has always been as secondary officials who have served the priestess in a secular function, such as leading her horse. Prior to the origin of state religion, each male of standing was paired with a female, usually a sister. Her function was to manipulate the spirit which gave him status and power; one can detect traces of the sister-kami concept and the sibling-deity myth in this arrangement.

With the creation of a state religion by Sho Hashi in a.d. 1429, state-appointed priestesses (noro) were given the responsibility for the supervision over and practice of kami worship. Present leadership is still dominated by females and reflects the traditional place of women in the religious life of the Okinawan people.

RELIGIOUS LEADERSHIP

Contemporary Okinawan religious offices2 are organized according to the following structure:

Priestess: Many communities have a noro-nuru who may or may not be a resident priestess. She is the chief official for religious matters and commands the greatest amount of respect. Most noro are assisted by another woman. Except for a few new villages every old settlement has a resident representative of the founding house (niigami) who ranks second only to the noro. In those villages lacking a resident noro, the village niigami is the ranking priestess for that village. Unlike the noro the niigami seems always to have been unrestricted so far as marriage is concerned and usually resides in her husband's house. When ritual is conducted in her village by the noro, the niigami serves as her assistant. In the larger communities such as Nago there may be more than one niigami because there may be more than one founding house. Nevertheless one niigami is always designated senior to the other.

In the villages of Okinawa (especially of the central and southern part) a fourth priestess is found: she is the kudii. Kudii are "called" by kami to represent the kin group in all ritual services on behalf of the kin. Special kudii may be appointed to pray for the kin group at the sites of former castles; they are called "Nakijin Kudii," "Shuri Kudii," or "Nanzan Kudii." On major ritual occasions all kudii of a kin lineage may pray together. If a kin group is large enough for a special kudii or not, it is a responsibility of the sib or lineage kudii to pray to the former national sites.

Household Mother: While not a kami-person, the mother of each household is responsible for the ritual of her family. She is the religious leader of the family, and becomes so at the time of her marriage.

Shaman Yuta: Yuta, unlike the household mother, may be considered kaminchu and may be male or female. The yuta are utilized for their supernatural diagnostic skill, but sometimes they specialize in another function, such as prayer. If kami trouble is the basis for all human trouble, someone must possess the ability to determine which kami is offended and how to rectify the problem. The yuta are important persons, therefore, for those who believe in supernatural intervention. Yuta do not inherit their position but are "called" to it by way of a traumatic experience which may be spiritual, physical, and mental in nature. The word "yuta" means "to shake."

Male Functionaries: Most religious functionaries are female; some of lesser importance are not. The ranking village male is the niitchu. Niitchu serve as assistants to the village niigami. Both niitchu and niigami are of the founding family of the village; both are the eldest of their sex in the founding family, and are siblings. In addition to the niitchu there were other males who traditionally assisted in ritual matters: they served ceremonial wine, carried a large fan, beat the ceremonial drum to sacred songs, cleaned and prepared ritual sites, and collected taxes for the payment of ceremonial expense.

The Fortuneteller (sanjinsoo) is also a male functionary. Fortunetellers are not considered as kami-persons; their knowledge is derived not from supernatural revelation but from the intelligent usage of the lunar almanac, I Ching, and other books on occult lore. Among the duties of the "educated" fortuneteller are: the selection of the right time for certain actions (such as buying, selling, or moving) or rite events (such as engagement and marriage). They are also consulted for selecting the the location of good places for wells or tombs; suggestion in personal names and the recommending a course of action for the coming year.

Buddhist Priests (booji) are scattered throughout the island and are found especially in the cities and the towns. Their chief function seems to be the care of temples and officiation at funerals. They also sell talismans and protective amulets. Booji are also said to exercise the power to remove ghosts and encourage their return to the family tomb. The belief in ghosts is related to the conviction that if death takes place violently or unnaturally the spirit must hover near the place of death and can find no rest until it, in turn, has caused a death. Booji are also called on to cremate the bodies of persons who are guilty of serious criminal acts or who bring disgrace upon the kin group. When this happens a body is denied burial in the family tomb. After cremation the ashes are interred with simple rites in the temple or temple yard.

LACK OF FORMAL PUBLIC WORSHIP SERVICES

The Western man identifies religion with formal services of public worship. He is conditioned to the prayer service, the mass, and the preaching service. Okinawan religious tradition is characterized by private ritual services, attendance at which is usually limited to the priestess and her attendants. Neither group singing nor religious education is in their experience and, under the circumstances, both are unnecessary.

RELIANCE ON RITUAL ACTION

The central concern with Okinawan religious practice is the maintenance of a partnership between the various kami and man. The focus is not, therefore, on obedience to a set of commandments, to a book of Scripture, or to the dogma of an institution; it is an interplay between the ancestor of the past and the living of the present, and between the kami who affect nature and agricultural man. How is this relationship strained? In a number of ways:

Failure to maintain proper ritual rites with ancestors.

Erroneous or improper ritual action.

Defilement of sacred places.

Violation of social values.

Pollution: Anything offensive to kami such as childbirth, sex, blood, death, sickness, disease, tombs, bone washing, visitation of major sites of worship by the male, visitation of birds on the ancestral shrine in the house, or a recently widowed woman.

Misdeeds of Ancestors: Punishment is thought to be passed from father to son until kami are pacified.

Taboo: Things and acts offensive to kami, such as the spilling of blood or taking of life in a newly sown rice paddy; (in the north) working on the 8th, 18th, or 28th days of the lunar calendar (these are taboo days when the kami are thought to descend to the mountains and fields); male presence in the sacred utaki (groves); robes and other clothing of the noro; houses of sickness; death; childbirth (taboo for noro); fishing boats (taboo for women); names of deceased members of a household (sometimes another name is obtained from the Buddhist monk).

Carelessness or openness to failure or danger on ones "bad luck" year: every 12 years from the first year of birth.

To the believer kami are very real. I had occasion to observe a devout middle-aged Okinawan woman who came to the Sonohan Utaki Stone Gate, just outside the site of the ancient castle at Shuri. Arriving with a friend she had come to pray for a sick child who was hospitalized at Shuri. The ceremony was short, lasting a total of not more than 10 minutes. Upon approaching the stone censer in front of the shrine she squatted upon her legs. Three white strips of paper were placed on top of the censer; on this paper she carefully placed five small bundles of black charcoal sticks. In front of the censor and to each side of it she put two small bottles of rice wine. An offering of what appeared to be paddies made of cooked rice was placed between the wine bottles. After placing the offering, the woman clapped her hands twice, folded them before her, bowed her head and began to offer prayer. This was punctuated from time to time with the head being raised, and the hands being lifted with the palms up. After talking with me for a few minutes, the woman's friend joined her, moving to her left side and to the rear about two feet. She too offered prayer, remaining in place until her friend concluded the ceremony. Following the closing prayer, wine was poured over each bundle of charcoal, the remaining elements were wrapped up and departure was made without any further action. When I asked the mother's friend if the mother was confident that the kami would help her child, she smiled and said, 'yes.' Of interest was my brief conversation with a young man who had driven the women to the shrine. When I asked him what the women were doing he said he did not know. He then got into the car, turned on the car radio and turned to some music which he sat enjoying.

Ritual sites, such as the Sonohan Utaki Stone Gate, are called ugwanju (prayer place), the central object of which is a censer. Four types of prayer places are found on Okinawa: national sites which were formerly important in state religion (Seefa Utaki is one example), community sites (the shrine at Awa is an example), kin group sites (tombs and national sites), and household ritual sites (the ancestral shrine and hearth are primary ones).

THE PLACE OF ART AND MUSIC

Europe is noted for its great heritage of Judeo/Christian art and magnificent churches. In European culture the colors are rich, the buildings are distinctive, and the music has endured from generation to generation. Even a brief survey of most Christian hymnals will reveal the influence of Europe and American religious practice. One will look in vain for this kind of development in Okinawa; here one finds a simplicity of both style and color and a total lack of spiritual public singing in worship. So far as I can determine there has been little development of religious mythology in art, no production of pictures of religious heroes and no creation of sacred scriptures peculiar to an indigenous religion. One Buddhist temple, the Enkan-chi, once contained some Buddhist scriptures donated by the king of Korea. This temple was destroyed by the Satsuma in 1609 and with it the scriptures. But aside from the Omoro-Soshi (a 22-volume anthology of ancient verses), practically no religious writing of antiquity exists.

There is good reason for this lack of material. The wars of the past have destroyed valuable property ; the Second World War raged around Shuri, leaving practically nothing. Then too, Okinawan religion, both indigenous and foreign has been largely "caught" not taught. It is a part of the fabric of the Okinawan way of life. This reflection of culture is very evident in the lack of bright colors and the simplicity of dress by the kami-people, who are the clergy of Okinawa.

ACCOMMODATION OF FOREIGN RELIGIONS

Okinawan thought, uneffected by the Greek insistence upon rationality, does not seem bothered by the lack of an organized, systematic religious belief. It neither possesses nor encourages the development of a systematic or dogmatic theology. This in no way implies a lack of faith. Faith in kami-spirits is the key to both the folk religion of Okinawa and its more contemporary form of religious expression which has been influenced by Shintoism and Buddhism from Japan, and Toaism and Confucianism from China.

I think it fair to say that the accommodation of foreign religions has come largely because religion in the Far East is experienced as a way of life, not an academic subject to discuss. As Japan, China, and Korea have influenced the social fabric of Okinawan life, religious influence has come as a part of the total impact.

Not to be minimized is the deliberate attempt on the part of the Japanese government from the time of its annexation of Okinawa (1879 to 1945) to instill a pro-Japanese cultural bias on the one hand and a distaste for Okinawan culture on the other.

LACK OF UNIFORM RELIGIOUS PRACTICE

Formerly, communication with members of other villages was discouraged; marriage outside the village was forbidden. The word "shima" often used in the naming of villages means "island." This attitude toward others outside the village and outside the kin group has not encouraged the free exchange of ideas, religious or otherwise.

One should not be surprised to find differences in religious practices not only from one area of Okinawa to another but from village to village.3 Any description of religious practice is a general one; for accuracy one must study each specific village or area. The reader would find it interesting to compare and contrast the various modes of religious practice and utilization of religious symbols throughout Okinawa Shima.