Читать книгу Pulp - Robin Talley - Страница 10

Chapter 2 Monday, June 27, 1955

ОглавлениеJanet had made a terrible mistake.

Two weeks ago, when she’d written the letter, she’d still been flush with her discovery. She hadn’t been thinking clearly.

But her mother was always telling her she was rash and reckless, and Janet had finally proven her right: it was only after the postman had already whisked her letter away that she’d realized a reply could come at any time. That it would be dropped into the family mailbox alongside her father’s Senate mail, her mother’s housekeeping magazines and her grandmother’s postcards from faraway cousins. That anyone in the family could reach into the mailbox, open that letter and discover the truth about Janet in an instant. And that they could realize precisely what that meant.

So Janet had spent every afternoon since perched by the living room window, listening for the postman’s footsteps on the walk.

Each day, when she heard him coming, she leaped to her feet and tore out the front door. Sometimes she beat him there and burst outside while he was still plodding up the steps to their tiny front porch. On those days, she forced a smile and held out trembling fingers to take the pile of letters from his hand.

Other days she was slower, and stepped outside just as he’d departed. Those days she pounced on the stuffed mailbox, flinging back the lid where JONES RESIDENCE was written in her mother’s neat hand.

Then there were afternoons like this one. When Janet was too late.

She’d made the mistake of getting absorbed in her reading, and when she heard the slap of brown leather filtering through the window glass she’d told herself it was only the next-door neighbor, a tall Commerce Department man who left his office early in the evenings and never looked up from polishing his black-rimmed glasses.

And so Janet’s eyes were still on the page in front of her—it was one of her father’s leather-bound Dickens novels; Janet’s parents had been after her to read as many classics as she could before she started college in September—when the mailbox lid clattered. Before she realized what had happened, her mother’s high heels were already clacking toward the front door. “Oh, there you are, Janet. Was that the postman I heard?”

Janet bolted upright, the Dickens spilling from her lap. She bit back a curse as she knelt to pick it up, smoothing back the bent pages as her mother frowned at her. “Really, Janet, you must take more care with your father’s things. And what is that getup you have on? You know better than to wear jeans in the front room, where anyone walking by could see you.”

“Sorry, ma’am.” Janet tucked the volume under her arm and stepped past her mother, narrowly beating her to the door. Janet was an inch taller than Mom now, and her legs were still muscled from cheerleading in the spring.

She jerked open the front door and slid her hand into the mailbox before Mom could intervene. Three letters today. Janet tried to angle her shoulders to shield the mail from view.

The first two letters were for her father, in official government envelopes with his address neatly typed on by their senders’ secretaries. The third letter bore Janet’s name.

It had come.

A short, sharp thrill ran through her as her fingers reached for the seal. Would this be the day everything changed?

Two weeks ago, she’d discovered that slim paperback in the bus station. That night, she’d read every page and found herself so enraptured, so overwhelmed, that she couldn’t help writing to its author. Now here it was—a reply. The author of that incredible book had written a letter just for Janet.

But Mom was still standing right behind her. Could Janet slip the letter into her blouse without her seeing?

“What’s gotten into you today?” Mom reached over Janet’s shoulder and plucked all three letters from her hand. Simple as that. “What’s this one with your name?”

“It’s nothing.” Janet ached to snatch the letter back, but forced herself to breathe instead as Mom tucked her finger behind the seal. Everyone in the family had always felt free to open Janet’s mail. She was eighteen years old, but still a child in their eyes. She’d have to think of a lie quickly.

The letter had been addressed to Janet by mistake. That was what she’d say. Whoever had sent it must have found her name on some list of recent high school graduates.

No, of course Janet couldn’t possibly imagine what the letter might refer to. She’d never heard of any “Dolores Wood” or “Bannon Press.” As a matter of fact, the letter could be a cleverly disguised Communist recruitment tool. For safety’s sake, they really ought to burn it before the neighbors saw.

Though the idea of burning that letter, before she’d even had a chance to read it, made tears prick at Janet’s eyes.

“Oh, it’s from the college.” Mom withdrew a single sheet of paper from the envelope and scanned it. “It isn’t important. Only a packing list.”

“The college?” Janet hadn’t even glanced at the return address on the letter, but there it was. The letter was from Holy Divinity.

Janet couldn’t believe she’d been so foolish.

“Well, you won’t be needing this.” Mom tucked the letter into the pocket of her apron. “They must send it out to all the new girls, without regard for which will be moving into the dorms.”

Janet nodded, hoping her mother couldn’t hear her heart still thundering in the silence.

“Are you all right?” Mom frowned again. “You look flushed. Your father and I had planned to go to the club for dinner, but if you need us to stay home—”

“It’s nothing, ma’am.” Janet shook her head, but she could feel blood rushing to her cheeks under her mother’s scrutiny. “I, ah—I have to get ready for work or I’ll be late.”

Mom’s frown deepened. “I didn’t realize you were working tonight.”

“I am.” Janet wasn’t. Another stupid, rash thing to say. Now what could she do? Put on her uniform and show up at the Soda Shoppe, ready to trot milkshakes out to station wagons on her night off?

To put off that decision, Janet dashed past Mom into the row house and ran up the narrow wooden stairs, her footfalls echoing behind her. Dad was always after her not to run in the house, saying it would disturb her grandmother’s rest, but Dad wasn’t home. Besides, Grandma always said it did her heart good to hear a child scurrying about the house and that Dad should shut his cake hole.

Janet reached the second-floor landing and threw open the door of her small bedroom, the hot air hitting her like a steaming kettle. The room was the same as always—the bed neatly made with its delicate pink spread, the flowered wallpaper that was starting to peel around the edges after a decade of Washington summers, the round mirror over her dresser with photos tucked into the frame. They were school portraits of her friends, mostly, plus an old yearbook photo of Janet and Marie in their cheerleading uniforms with pom-poms at their hips, their bent elbows lightly touching.

That photo was Janet’s favorite.

Marie, her shiny hair framing her dark-rimmed glasses and always-gleaming smile, had been Janet’s best friend all through school. For years they’d done everything together, sitting side by side in every assembly and every lunch period. In junior high they’d been the only two girls to enter the science fair at the boys’ school, growing mold in carefully labeled jars and winning a red ribbon for their trouble. In high school they’d practiced their cartwheels and splits on the football field, giggling every time they fell onto the grass and making up silly variations to the official St. Paul’s cheers. Janet had never been happier than when one of the chants she made up provoked a fresh bout of laughter from Marie.

Marie was a year ahead of Janet, though, and after she graduated Janet’s senior year had been lonely indeed. Marie had spent the year at secretarial school, learning to type and take stenography and do other important things while Janet sat in Latin class again, wearing her childish uniform blazer and holding out her palm for the nun to strike when she forgot a conjugation.

That morning, eager to hear her voice again, Janet had tried to call Marie, but she was out, as usual. Janet had been forced to leave a terribly awkward message with her mother instead. Mrs. Eastwood had always seemed to think Janet was somewhat odd, and she could only have made that impression worse with the way she’d stumbled through the quick call.

She’d tried to explain that she was only calling to ask about Marie’s job search. Now that she’d finished her business classes, Marie had been so busy with applications and interviews they hadn’t seen each other in weeks. Janet was desperate to talk to her again.

Most of all, she longed to tell Marie about the book she’d found. Janet couldn’t wait to hear what she thought of it—even though she could probably guess. Despite their shared memories, Janet knew it was unlikely Marie would want to remain her friend once she knew her secret. No normal person would.

Still, Janet was determined to tell her. There was no one else she could talk with about this. Certainly no one in her family. If her parents ever found out... Janet didn’t dare to think of it. Marie was the only one who might be willing to listen.

Janet broke her gaze from the glossy photo and knelt on the floor next to her bed. She lifted the pink spread and in a single, practiced move, slid her hand between the mattress and bedframe until her fingers reached the cracked paper spine. She checked again to make sure the bedroom door was fully closed before carefully withdrawing the book from its hiding place.

She needed to find a better spot for it. The weight of the mattress had not been kind to the binding. The cheap glue had already started to come undone, and a few pages were loose, but Janet tucked them back into their proper place. She sank onto the rug between her bed and the wall, where she’d be out of view of anyone barging in, and gazed down at the book’s cover.

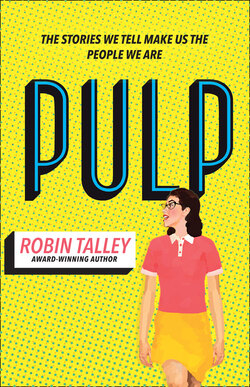

Its background was a deep, glaring shade of red. That color was what had first caught Janet’s eye when she’d spotted the wire rack full of books at the Ocean City bus station. It had been surrounded by similarly glaring paperbacks—detective fiction, gangster stories, the sorts of books you saw certain men reading on the streetcar. The sorts of books her father dismissed with a sniff as trash.

But it was the drawing, the strange image that stood out starkly from that palette of red, that had held Janet’s eye for far longer than it should’ve.

It showed two girls, neither much older than Janet herself. One girl had blond hair and one brown. Both had long, dark eyelashes and full, red lips. The dark-haired girl perched on a bed in the foreground, her legs long and slim, her skirt pulled up above her knees. Her green blouse was unbuttoned far enough to show a hint of pale slip beneath and a curve of bosom above. The blond girl stood farther back, dressed in nothing but a white nightgown that clung to her curves and a pair of deep brown stockings, the hems at the thighs fully visible below her shockingly short gown.

The dark-haired girl sat twisted around on the bed, so that the two girls’ eyes met. The blond’s lips were parted, as though to speak to the other girl.

Or, perhaps, to kiss her.

Janet blushed at the thought, as she did every time. Though she knew well enough that within the book’s pages the girls did kiss, and even more besides.

Janet had only glanced around the bus station for a tiny moment before she slipped the book under her blouse. It still mortified her to remember. The price on the cover was thirty-five cents, and Janet had had two dollars in her purse, but she couldn’t imagine showing her purchase to that smirking boy behind the cash register.

That novel was the only thing Janet had ever stolen in her life. She’d read it straight through that first night, and she’d stared at the cover in secret every day since.

Yellow letters above the drawing screamed the book’s title, A Love So Strange. Smaller black text below read, “A world spoken of only in whispers, where women enjoy twisted passions. Betty knew it was wrong...but she was powerless against her unnatural attractions.”

At the bottom, in the smallest type on the cover, was the author’s name, Dolores Wood.

Janet had read each of those words more times than she could count. Still, whenever she gazed at that cover, her eyes were pulled to the illustration. To the girls’ eyes where they met across the room. To the shapes of their bodies in their skimpy clothes.

Janet pressed one finger into the dip in her lower lip. Her breathing had grown heavier.

She’d never imagined there was a word for the strange feelings she’d had so many nights, alone in her bed, in the dark silence of her room.

Lesbian.

The word made her shudder. But it sent a tiny shiver down her spine, too.

Janet had never understood, not until she turned the thin brown pages of Dolores Wood’s novel, that other girls might feel the way she did. That a world existed outside the one she’d always known.

It had never occurred to her that life could be different from what had already been set out for her. Ill-fitting uniforms and nickel-sized tips at the Soda Shoppe. Her parents pausing in the dining room to listen as Janet made phone calls in the kitchen. Solemn history and mathematics lessons taught by stern-faced nuns. Then, someday, an equally solemn wedding to a faceless man, and a future spent baking solemn casseroles for solemn, faceless children.

Janet had never thought books like A Love So Strange could be written, let alone published and sold—and right in the middle of a public bus station, too. She’d never imagined some girls might actually do the sorts of things Janet had only furtively imagined in those brief, solitary moments between waking and sleeping.

Reading A Love So Strange had made Janet remember some things differently, too.

The way she and Marie had talked and laughed while they’d practiced their cheers. The way they’d touched, lying side by side on Marie’s back porch while her parents were out on warm summer afternoons.

The way Janet would trail her fingers along Marie’s bare arm after she’d pointed out some item in a magazine. The way Marie would smile and wait several moments before she drew her hand away.

When Janet thought of kissing a girl, the way girls kissed other girls in the pages of Dolores Wood’s book, she always thought of kissing Marie. When she thought back to Marie’s smiles on those lazy afternoons, she wondered if Marie might feel the same way, too.

If Janet could only show that book to Marie, it could change everything.

Still, she should never have sent the letter.

She’d been so foolish, to dream of writing a book of her own. To scrawl out that letter with all her silly, immature questions for Mrs. Wood. To address it to the publisher listed on the book’s cover and drop the envelope into the mailbox, as though it were as simple a matter as sending in for a catalog.

Downstairs, she heard the front door open, then close again. “Janet! Come back down!”

At the sound of her mother’s voice Janet scrambled to her feet, shoving the book back into its hiding place. She winced as she felt the cover bend. “Coming, ma’am!”

Only then did Janet remember she’d said she had to work tonight. Mom would wonder why she hadn’t already changed into her uniform. She tried to think of another lie—she’d checked her schedule upstairs and realized she wasn’t working that night after all; there, that one was simple enough—but all thoughts of lies and excuses left Janet’s mind when she reached the bottom of the staircase and saw Marie in the foyer, smiling at her now-apronless mother and fiddling with the strap of her purse.

A delicious thrill ran through Janet all the way to her toes. She wished she’d thought to reapply her lipstick.

Marie looked as she always had, with each dark curl in place, her glasses polished to a gleam. Yet she looked older than usual, too, somehow. Her suit was neat, the skirt perfectly tailored where its hem fell around her calves. The jacket was a matching blue flannel, and the string of pearls her parents had given her for her eighteenth birthday was wound around her neck.

Janet had never seen her friend look so much like a real grown-up. A lovely grown-up, at that.

“There you are, Janet.” Mom turned from Marie with a lingering smile of her own. Janet’s mother had always been fond of Marie. She talked about her using words like stable and settled. Especially when she sought to admonish Janet.

Janet ignored her and bounced toward Marie. “I’m so glad you came! I have so much to tell you.”

“It’s been ages, hasn’t it?” Marie’s smile was wide enough to match Janet’s own. “I’m terribly sorry I missed your call this morning. I was at an interview.”

“An interview.” Janet’s eyes drifted down to Marie’s neat suit. She flushed. “Of course.”

“I’ve been so nervous.” Marie smiled, and fumbled again with her purse. “It’s wonderful to see you, though.”

“Marie has the most exciting news.” Mom held out a hand, ushering them into the living room. She didn’t approve of dawdling in the foyer. “I’ll bring you girls some refreshments.”

Mom left for the kitchen, where she could still overhear every word they said. Even so, as Janet and Marie took seats on the sofa, Janet leaned in close and said, “I was just looking at our photo from the cheerleading squad last year. I remember that as if it was yesterday.”

“Do you?” Marie smiled. She looked even more sophisticated from this distance. “It seems like a hundred years ago to me.”

Janet’s smile began to fade.

“There we are.” Mom set down a tray of chocolate chip cookies and two glasses of milk, sitting primly in the armchair opposite the cold brick fireplace. “Now, Marie, I simply can’t wait one moment longer to hear what Janet thinks of your news.”

“Well, then, what’s your news, Marie?” Janet wished Dad were here, so they could smile together at this ostentatious etiquette. Mom treated every visitor like President Eisenhower.

Laughter sparkled behind Marie’s eyes, too, but, ever demure, she didn’t let it reach her lips. “I’ve been offered a job, just today. I’m going to be a typist at the Department of State!”

“Marie!” Janet clapped her hands. “That’s marvelous! That’s the kind of job we all dreamed of having, do you remember?”

“Of course.”

Any sort of government work had seemed glamorous to the girls of St. Paul’s Academy. Their mothers had all gone to work as “government girls” during the war, of course, but they’d retired once the men came home. These days only the most elite girls, those capable of passing stringent tests and maintaining the highest personal decorum, were hired to work as government secretaries and typists. Janet’s own distant ambition, of studying journalism in college and working for a newspaper or magazine someday, was far less exciting.

Working for the State Department was perhaps the most prestigious government position of all, surpassed only by working in the White House itself. At the State Department, a girl might meet a famous ambassador or foreign film star. Perhaps there might be a need to travel overseas, to take dictation for an important summit in Paris or Rome, or even some far-flung country like China.

It was all temporary, of course. The true goal, spoken of only through happy whispers over cafeteria lunches, was to meet a government man with an impressive job of his own, perhaps one with a title like director or even undersecretary. Once you were married, you’d leave your job to set up housekeeping so you’d be ready when the children came along.

Of course, though, it was far too early for Marie and Janet to think about any of that.

“Well, I’m not surprised,” Janet said, still beaming. “Didn’t you have the highest marks of all the girls coming out of school?”

Marie cast down her eyes. “Thank you, Janet. I was hoping we could go out tonight to celebrate, but your mother said you’re working.”

“Oh, no, I’m not. Let’s go celebrate!” When Mom raised her eyebrows, Janet hastily added, “Sorry, ma’am, I was confused about my schedule. May I please have permission to go out with Marie?”

“Certainly.”

“Wonderful! If we leave now we can catch the streetcar pulling in.”

Marie rose instantly, nodding toward the untouched milk glasses. “Thank you for the refreshments, Mrs. Jones.”

“Of course.” Mom’s plastered-on smile stayed firm as she eyed Janet’s plain blouse and jeans. “Janet, Marie and I will wait here while you change.”

Janet longed to be out the door, but her mother was right. Janet rarely wore much makeup, and most days she preferred Bermudas and button-downs to frills and fashion, but no restaurant in Georgetown would let her in for dinner wearing pants. “I’ll be fast, I promise.”

She ran upstairs, exchanged her jeans for a simple plaid skirt and stockings, and ran back down. Mom eyed her again, probably wishing Janet had at least taken the time to run a comb through her short blond curls, but all she said was, “You girls have a lovely evening. Marie, please do send your mother my regards.”

“I will, ma’am, thank you.”

Janet grabbed her purse, took Marie by the arm and pulled her out the door before her mother could launch into a new round of pleasantries. The streetcar was already clanging as it approached the end of their block, and the girls had to run. Marie’s high heels made her stumble, and Janet, in her ballet flats, was faster. She stepped onto the wide streetcar platform and held out her hand to help Marie aboard as the car pulled out, both girls laughing so hard the driver admonished them with a glare as they started north up Wisconsin Avenue.

It was exhilarating to be going out without her parents on the spur of the moment this way. Janet was certain Mom wouldn’t have allowed it if she’d been with anyone but Marie, and she flushed with pleasure at the thought.

“I thought we’d go to Meaker’s for dinner.” Marie squirmed through the crush of after-work passengers, struggling to keep her footing as the car lurched forward. A man in a fedora reached for her elbow to steady her, nearly dropping his cigarette.

“That sounds perfect.” Janet smiled at the man until he released Marie’s arm.

The two of them made their way to the back of the car. Janet couldn’t stop herself from staring down at Marie’s clothes. The perfect fit of her suit. The way she stood gripping the ceiling strap, with one heel turned out to steady herself as the streetcar rocked over bumps. The shape of her legs, so pretty in her stockings. It reminded Janet of—

The book. It reminded Janet of the picture on the cover of A Love So Strange.

She swallowed and tried, again, to make herself breathe.

“Are you all right?” Marie peered at Janet tremulously as the streetcar swung beneath them.

“I’m fine.” Janet had never felt finer, in fact.

“You’re sure? Meaker’s is just another block, but we can catch the car going the opposite way if you need to go home.”

“I don’t want to go home.” As they reached their stop, Janet hopped past Marie down to the sidewalk, glad to feel earth beneath her feet once more. She wasn’t quite sure what type of place Meaker’s might be, but she didn’t care. “We have to celebrate, don’t we?”

Marie smiled and took Janet’s arm. “We certainly do.”

The restaurant turned out to be a small, quiet place on a side street off Wisconsin, with worn white tablecloths and dim lamps overhead. The girls were seated right away, and Marie ordered for both of them, smiling up at the waiter with a poised nonchalance Janet envied.

Marie was so strong and composed. She showed none of the clumsy awkwardness Janet always felt. It was a lucky thing Marie had wanted to celebrate with her.

Janet smiled fondly across the table as two drinks appeared in front of them. She recognized the glasses from her parents’ cocktail parties. “What are these?”

“Martinis.” Marie smiled and lifted her glass. Janet imitated her, trying to look equally refined. The waiter hadn’t said a word about identification, so he must’ve thought the girls looked older than their eighteen and nineteen years. No one here at Meaker’s, it seemed, had realized Janet was nothing but a plain schoolgirl. “My father always orders them on special occasions.”

Janet took a swallow. The drink was cool, with a hint of spice. It tasted very adult. She could picture the girls in A Love So Strange sipping drinks like these alone in their apartment one evening.

Marie asked about a friend from high school she hadn’t seen lately, and soon they were caught up reminiscing about their high school days. Before long, Janet’s glass was empty and a fresh drink had taken its place. She wasn’t sure exactly how much time had passed, and she couldn’t quite remember what had just been said that had made her laugh so hard. All she knew was that Marie was laughing, too, and that was all that seemed to matter.

Their food had arrived, but Janet had barely eaten. Marie’s pot roast and potatoes were in a similar state.

“So this fellow Mom wanted me to go out with tonight,” Marie was saying, as she took another sip, “he’s a college man in town for the summer. Dartmouth. His uncle works with Dad at Treasury, and he’s a dreadful bore—”

“How do you know he’s a bore?” Janet interrupted. “Have you met him already?”

“No, no, but you know how these college men are.”

Did she? This was the first time Janet had heard Marie talk about college men that way. Or was it merely the first time Janet had noticed it? Had Dolores Wood’s book changed the way she saw everything, all at once?

“In any case,” Marie went on, “Dad’s up for a promotion—that’s why they’ve been going to the club so often—and so Mom thinks I ought to go out with this Harold Smith fellow, since his uncle would be Dad’s boss if he gets the new job. But I told Mom I didn’t want to go out with some strange college man. I said I wanted to go celebrate with my best friend. Mom huffed and puffed, but what could she say in the end? Soon I’ll be earning my very own paychecks, and she and Dad won’t have any say over what I do.”

“Really?” Janet hadn’t thought of that. “Won’t you go on living with them, though?”

“Well, sure—unless I were to move in with some of the other State Department girls, I suppose. A few of my business school classmates invited me to share an apartment, but I didn’t have a job yet so I had to tell them no. Wouldn’t that be magnificent, though? Not to have to follow anyone else’s rules? To be able to go out whenever you chose, with whomever you wanted?”

Janet nodded, but in truth she couldn’t imagine such freedom. Until she’d read A Love So Strange, her dreams had only extended so far as a college dorm. It seemed a lovely idea, though, to be away from her family’s watching eyes.

But in a dorm, of course, there were still strict rules and curfews. Living at Holy Divinity, only a mile or so up Wisconsin Avenue, might be even more restrictive than living at home. At least in the house Janet was allowed to use the phone when she chose, provided Mom, Dad and Grandma didn’t need to make a call.

“I must admit, I’m a bit nervous.” Marie bit her lip, and Janet forgot all her musings about college and apartments.

In their place, her hope flared bright. Could Marie be nervous for the same reason as Janet?

“What will everyone in the office think of me?” Marie gazed down into her drink. “What if I don’t keep up with the other girls? What if my boss expects more of me than I can do?”

Janet tamped down her disappointment. “Oh, you don’t need to worry about that. They’ll all adore you. How could they not?”

Marie smiled up at her, yet she still looked bashful. “That’s kind of you to say.”

“I’m not being kind. I’m being honest. You’re perfect, Marie.”

The words were out of her mouth before Janet could think about how they sounded. Now she felt bashful, too.

Yet Marie didn’t look embarrassed as she held her gaze across the table.

Neither of them spoke, but something passed in that shared look that Janet couldn’t have named. It buzzed through her with an energy she’d never known.

Unless that, too, was solely in Janet’s imagination.

The waiter came to take their empty glasses, inquiring if they needed anything else. His eyes were on Marie and she answered for them both, in a voice so grown-up Janet couldn’t believe she’d ever found cause to be nervous about anything. “No, thank you. I suppose it’s getting late.”

The waiter left, and Marie withdrew a few bills from her purse and tucked them under the glass. Her every movement was mesmerizing. “We ought to catch the streetcar. Your mother will be worried.”

“Oh, forget my mother.” Janet laughed and climbed awkwardly to her feet, holding the table to right herself.

Marie laughed, too, and followed. On the way out of the restaurant, she took a matchbook from the front desk and slipped it into her purse with a smile. Janet grabbed one, too, giggling.

The sidewalk was dark under the burned-out streetlight as the girls stumbled outside, the pavement grit caking under their heels. Up ahead, on Wisconsin, people were walking quickly along the sidewalk, but out here there was no one out but the two of them.

“I’m glad you didn’t have to work tonight after all.” Marie tucked her arm into Janet’s as they began to walk. “This afternoon, the very instant the man at State told me I’d gotten the job, I knew the only person I wanted to celebrate with in all the world was you.”

Janet closed her eyes, tasting the words.

If she were Sam, the main character from A Love So Strange—if she’d had Sam’s courage, her knowledge of girls, her understanding of the world—she would kiss Marie. Right where they stood.

Sam didn’t bother with waiting. She went after what she wanted.

Of course, even Sam wouldn’t dare kiss a girl out in the open darkness, where anyone might see them. But maybe they could move somewhere out of sight. Duck beneath the awning of the shuttered corner shop, perhaps.

Sam would’ve said a clever line, too. Something witty and alluring.

Janet opened her eyes.

She meant to think of something clever. Truly, she did. In the end, though, the words that came out were, “Um...let’s go over there.”

Marie didn’t seem to mind her abruptness. Her eyes were bright, her answer quick. “Yes, let’s.”

They hurried around the corner and stood, silent, their eyes locked on one another’s. Janet could no longer think about books or jobs. She couldn’t think about anything but Marie and that look they’d shared across the table.

She closed her eyes. And all at once, there in the darkness, it was happening. It was real.

Janet was kissing her.

It was madness. She knew it was madness, because in that moment Janet could not have prevented herself from kissing Marie if all the world had tried to stop her. And so it was some time before she began to understand that Marie was kissing her back.

She could scarcely breathe. In all the world, there existed nothing but Marie’s lips on hers. Marie’s hair, soft under her hand. Marie’s body, pressed so close Janet could feel the seams in her flannel suit.

“Hey!”

The girls sprang apart, four feet of space materializing between them in an instant. There was no way to tell where the shout had come from.

Who’d seen them? Would her parents find out? Already, before Janet had even truly found out for herself?

“Is it the police?” Marie whispered. Janet hadn’t even thought of that.

“Hey!” The shout came again. This time, it was punctuated by a round of laughter from high above. A girl’s laughter.

Whoever had shouted, it wasn’t the police.

Janet tilted her head back, looking for the source of the sound. Next to her, Marie did the same.

They both saw it at the same time. A girl, framed in an open window. An apartment two stories above the darkened store.

A man leaned toward her, and the girl ducked out of his way, still laughing, holding a bottle of beer. The girl’s eyes were locked on his.

She hadn’t seen Janet and Marie.

Only then did Janet feel the full weight of relief crashing down around her.

She lowered her gaze, locking eyes with Marie. Marie’s breathing was rapid, but a smile danced behind her glasses. The madness of their kiss had touched her, too.

The sound of the streetcar made Janet’s heart beat faster. It was late, and the next car may not come for some time. They’d have to dash for it.

She longed to take Marie’s hand—that was what Sam would’ve done—but she didn’t dare. Instead, they turned and ran in a single movement.

This time, Janet didn’t beat Marie to the curb. This time, they stayed together.

They climbed onto the sparsely populated car and took seats side by side. They didn’t dare to touch, but they watched each other carefully. After another moment, they began to laugh.

Janet waited for her heart to slow, for normalcy to retake her mind. Yet as long as she waited, it never came.