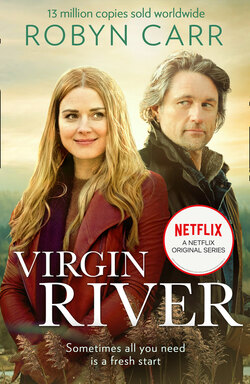

Читать книгу Virgin River - Robyn Carr, Robyn Carr - Страница 10

One

ОглавлениеMel squinted into the rain and darkness, creeping along the narrow, twisting, muddy, tree-enshrouded road and for the hundredth time thought, am I out of my mind? And then she heard and felt a thump as the right rear wheel of her BMW slipped off the road onto the shoulder and sank into the mud. The car rocked to a stop. She accelerated and heard the wheel spin but she was going nowhere fast.

I am so screwed, was her next thought.

She turned on the dome light and looked at her cell phone. She’d lost the signal an hour ago when she left the freeway and headed up into the mountains. In fact, she’d been having a pretty lively discussion with her sister Joey when the steep hills and unbelievably tall trees blocked the signal and cut them off.

“I cannot believe you’re really doing this,” Joey was saying. “I thought you’d come to your senses. This isn’t you, Mel! You’re not a small-town girl!”

“Yeah? Well, it looks like I’m gonna be—I took the job and sold everything, so I wouldn’t be tempted to go back.”

“You couldn’t just take a leave of absence? Maybe go to a small, private hospital? Try to think this through?”

“I need everything to be different,” Mel said. “No more hospital war zone. I’m just guessing, but I imagine I won’t be called on to deliver a lot of crack babies out here in the woods. The woman said this place, this Virgin River, is calm and quiet and safe.”

“And stuck back in the forest, a million miles from a Starbucks, where you’ll get paid in eggs and pig’s feet and—”

“And none of my patients will be brought in handcuffed, guarded by a corrections officer.” Then Mel took a breath and, unexpectedly, laughed and said, “Pig’s feet? Oh-oh, Joey—I’m going up into the trees again, I might lose you…”

“You wait. You’ll be sorry. You’ll regret this. This is crazy and impetuous and—”

That’s when the signal, blessedly, was lost. And Joey was right—with every additional mile, Mel was doubting herself and her decision to escape into the country.

At every curve the roads had become narrower and the rain a little harder. It was only 6:00 p.m., but it was already dark as pitch; the trees were so dense and tall that even that last bit of afternoon sun had been blocked. Of course there were no lights of any kind along this winding stretch. According to the directions, she should be getting close to the house where she was to meet her new employer, but she didn’t dare get out of her swamped car and walk. She could get lost in these woods and never be seen again.

Instead, she fished the pictures from her briefcase in an attempt to remind herself of a few of the reasons why she had taken this job. She had pictures of a quaint little hamlet of clapboard houses with front porches and dormer windows, an old-fashioned schoolhouse, a steepled church, hollyhocks, rhododendrons and blossoming apple trees in full glory, not to mention the green pastures upon which livestock grazed. There was the Pie and Coffee shop, the Corner Store, a tiny-one-room, freestanding library, and the adorable little cabin in the woods that would be hers, rent free, for the year of her contract.

The town backed up to the amazing sequoia redwoods and national forests that spanned hundreds of miles of wilderness over the Trinity and Shasta mountain ranges. The Virgin River, after which the town was named, was deep, wide, long, and home to huge salmon, sturgeon, steel fish and trout. She’d looked on the Internet at pictures of that part of the world and was easily convinced no more beautiful land existed. Of course, she could see nothing now except rain, mud and darkness.

Ready to get out of Los Angeles, she had put her résumé with the Nurse’s Registry and one of the recruiters brought Virgin River to her attention. The town doctor, she said, was getting old and needed help. A woman from the town, Hope McCrea, was donating the cabin and the first year’s salary. The county was picking up the tab for liability insurance for at least a year to get a practitioner and midwife in this remote, rural part of the world. “I faxed Mrs. McCrea your résumé and letters of recommendation,” the recruiter had said, “and she wants you. Maybe you should go up there and look the place over.”

Mel took Mrs. McCrea’s phone number and called her that evening. Virgin River was far smaller than what she’d had in mind, but after no more than an hour-long conversation with Mrs. McCrea, Mel began effecting her move out of L.A. the very next morning. That was barely two weeks ago.

What they didn’t know at the Registry, nor in Virgin River for that matter, was that Mel had become desperate to get away. Far away. She’d been dreaming of a fresh start, and peace and quiet, for months. She couldn’t remember the last time she’d had a restful night’s sleep. The dangers of the big city, where crime seemed to be overrunning the neighborhoods, had begun to consume her. Just going to the bank and the store filled her with anxiety; danger seemed to be lurking everywhere. Her work in the three-thousand-bed county hospital and trauma center brought to her care the victims of too many crimes, not to mention the perpetrators of crimes hurt in pursuit or arrest— strapped to hospital beds in wards and in Emergency, guarded by cops. What was left of her spirit was hurting and wounded. And that was nothing to the loneliness of her empty bed.

Her friends begged her to stave off this impulse to run for some unknown small town, but she’d been in grief group, individual counseling and had seen more of the inside of a church in the last nine months than she had in the last ten years, and none of that was helping. The only thing that gave her any peace of mind was fantasizing about running away to some tiny place in the country where people didn’t have to lock their doors, and the only thing you had to fear were the deer getting in the vegetable garden. It seemed like sheer heaven.

But now, sitting in her car looking at the pictures by the dome light, she realized how ridiculous she’d been. Mrs. McCrea told her to pack only durable clothes— jeans and boots—for country medicine. So what had she packed? Her boots were Stuart Weitzmans, Cole Haans and Fryes—and she hadn’t minded paying over a tidy four-fifty for each pair. The jeans she had packed for traipsing out to the ranches and farms were Rock & Republics, Joe’s, Luckys, 7 For All Mankind—they rang up between one-fifty and two-fifty a copy. She’d been paying three hundred bucks a pop to have her hair trimmed and highlighted. After scrimping for years through college and post-grad nursing, once she was a nurse practitioner with a very good salary she discovered she loved nice things. She might have spent most of her workday in scrubs, but when she was out of them, she liked looking good.

She was sure the fish and deer would be very impressed.

In the past half hour she’d only seen one old truck on the road. Mrs. McCrea hadn’t prepared her for how perilous and steep these roads were, filled with hairpin turns and sharp drop-offs, so narrow in some places that it would be a challenge for two cars to pass each other. She was almost relieved when the dark consumed her, for she could at least see approaching headlights around each tight turn. Her car had sunk into the shoulder on the side of the road that was up against the hill and not the ledge where there were no guardrails. Here she sat, lost in the woods and doomed. With a sigh, she turned around and pulled her heavy coat from the top of one of the boxes on the backseat. She hoped Mrs. McCrea would be traversing this road either en route to or from the house where they were to meet. Otherwise, she would probably be spending the night in the car. She still had a couple of apples, some crackers and two cheese rounds in wax. But the damn Diet Coke was gone—she’d have the shakes and a headache by morning from caffeine withdrawal.

No Starbucks. She should have done a better job of stocking up.

She turned off the engine, but left the lights on in case a car came along the narrow road. If she wasn’t rescued, the battery would be dead by morning. She settled back and closed her eyes. A very familiar face drifted into her mind: Mark. Sometimes the longing to see him one more time, to talk to him for just a little while was overwhelming. Forget the grief—she just missed him—missed having a partner to depend on, to wait up for, to wake up beside. An argument over his long hours even seemed appealing. He told her once, “This—you and me—this is forever.”

Forever lasted four years. She was only thirty-two and from now on she would be alone. He was dead. And she was dead inside.

A sharp tapping on the car window got her attention and she had no idea if she’d actually been asleep or just musing. It was the butt of a flashlight that had made the noise and holding it was an old man. The scowl on his face was so jarring that she thought the end she feared might be upon her.

“Missy,” he was saying. “Missy, you’re stuck in the mud.”

She lowered her window and the mist wet her face. “I…I know. I hit a soft shoulder.”

“That piece of crap won’t do you much good around here,” he said.

Piece of crap indeed! It was a new BMW convertible, one of her many attempts to ease the ache of loneliness. “Well, no one told me that! But thank you very much for the insight.”

His thin white hair was plastered to his head and his bushy white eyebrows shot upwards in spikes; the rain glistened on his jacket and dripped off his big nose. “Sit tight, I’ll hook the chain around your bumper and pull you out. You going to the McCrea house?”

Well, that’s what she’d been after—a place where everyone knows everyone else. She wanted to warn him not to scratch the bumper but all she could do was stammer, “Y-yes.”

“It ain’t far. You can follow me after I pull you out.”

“Thanks,” she said.

So, she would have a bed after all. And if Mrs. McCrea had a heart, there would be something to eat and drink. She began to envision the glowing fire in the cottage with the sound of spattering rain on the roof as she hunkered down into a deep, soft bed with lovely linens and quilts wrapped around her. Safe. Secure. At last.

Her car groaned and strained and finally lurched out of the ditch and onto the road. The old man pulled her several feet until she was on solid ground, then he stopped to remove the chain. He tossed it into the back of the truck and motioned for her to follow him. No argument there—if she got stuck again, he’d be right there to pull her out. Along she went, right behind him, using lots of window cleaner with her wipers to keep the mud he splattered from completely obscuring her vision.

In less than five minutes, the blinker on the truck was flashing and she followed him as he made a right turn at a mailbox. The drive was short and bumpy, the road full of potholes, but it quickly opened up into a clearing. The truck made a wide circle in the clearing so he could leave again, which left Mel to pull right up to…a hovel!

This was no adorable little cottage. It was an A-frame with a porch all right, but it looked as though the porch was only attached on one side while the other end had broken away and listed downward. The shingles were black with rain and age and there was a board nailed over one of the windows. It was not lit within or without; there was no friendly curl of smoke coming from the chimney.

The pictures were lying on the seat beside her. She blasted on her horn and jumped immediately out of the car, clutching the pictures and pulling the hood of her wool jacket over her head. She ran to the truck. He rolled down his window and looked at her as if she had a screw loose. “Are you sure this is the McCrea cottage?”

“Yup.”

She showed him the picture of the cute little A-frame cottage with Adirondack chairs on the porch and hanging pots filled with colorful flowers decorating the front of the house. It was bathed in sunlight in the picture.

“Hmm,” he said. “Been awhile since she looked like that.”

“I wasn’t told that. She said I could have the house rent free for a year, plus salary. I’m supposed to help out the doctor in this town. But this—?”

“Didn’t know the doc needed help. He didn’t hire you, did he?” he asked.

“No. I was told he was getting too old to keep up with the demands of the town and they needed another doctor, but that I’d do for a year or so.”

“Do what?”

She raised her voice to be heard above the rain. “I’m a nurse practitioner. And certified nurse midwife.”

That seemed to amuse him. “That a fact?”

“You know the doctor?” she asked.

“Everybody knows everybody. Seems like you shoulda come up here and look the place over and meet the doc before making up your mind.”

“Yeah, seems like,” she said in some self-recrimination. “Let me get my purse—give you some money for pulling me out of the—” But he was already waving her off.

“Don’t want your money. People up here don’t have money to be throwing around for neighborly help. So,” he said with humor, lifting one of those wild white eyebrows, “looks like she got one over on you. That place’s been empty for years now.” He chuckled. “Rent free! Hah!”

Headlights bounced into the clearing as an old Suburban came up the drive. Once it arrived the old man said, “There she is. Good luck.” And then he laughed. Actually, he cackled as he drove out of the clearing.

Mel stuffed the picture under her jacket and stood in the rain near her car as the Suburban parked. She could’ve gone to the porch to get out of the elements, but it didn’t look quite safe.

The Suburban’s frame was jacked up and the tires were huge—no way that thing was getting stuck in the mud. It was pretty well splashed up, but it was still obvious it was an older model. The driver trained the lights on the cottage and left them on as the door opened. Out of the SUV climbed this itty bitty elderly woman with thick, springy white hair and black framed glasses too big for her face. She was wearing rubber boots and was swallowed up by a rain slicker, but she couldn’t have been five feet tall. She pitched a cigarette into the mud and, wearing a huge toothy smile, she approached Mel. “Welcome!” she said gleefully in the same deep, throaty voice Mel recognized from their phone conversation.

“Welcome?” Mel mimicked. “Welcome?” She pulled the picture from the inside of her jacket and flashed it at the woman. “This is not that!”

Completely unruffled, Mrs. McCrea said, “Yeah, the place could use a little sprucing up. I meant to get over here yesterday, but the day got away from me.”

“Sprucing up? Mrs. McCrea, it’s falling down! You said it was adorable! Precious is what you said!”

“My word,” Mrs. McCrea said. “They didn’t tell me at the Registry that you were so melodramatic.”

“And they didn’t tell me you were delusional!”

“Now, now, that kind of talk isn’t going to get us anywhere. Do you want to stand in the rain or go inside and see what we have?”

“I’d frankly like to turn around and drive right out of this place, but I don’t think I’d get very far without four-wheel-drive. Another little thing you might’ve mentioned.”

Without comment, the little white-haired sprite stomped up the three steps and onto the porch of the cabin. She didn’t use a key to unlock the door but had to apply a firm shoulder to get it to open. “Swollen from the rain,” she said in her gravelly voice, then disappeared inside.

Mel followed, but didn’t stomp on the porch as Mrs. McCrea had. Rather, she tested it gingerly. It had a dangerous slant, but appeared to be solid in front of the door. A light went on inside just as Mel reached the door. Immediately following the dim light came a cloud of choking dust as Mrs. McCrea shook out the tablecloth. It sent Mel back out onto the porch, coughing. Once she recovered, she took a deep breath of the cold, moist air and ventured back inside.

Mrs. McCrea seemed to be busy trying to put things right, despite the filth in the place. She was pushing chairs up to the table, blowing dust off lampshades, propping books on the shelf with bookends. Mel had a look around, but only to satisfy her curiosity as to how horrid it was, because there was no way she was staying. There was a faded floral couch, a matching chair and ottoman, an old chest that served as a coffee table and a brick and board bookcase, the boards unfinished. Only a few steps away, divided from the living room by a counter, was the small kitchen. It hadn’t seen a cleaning since the last person made dinner—presumably years ago. The refrigerator and oven doors stood open, as did most of the cupboard doors. The sink was full of pots and dishes; there were stacks of dusty dishes and plenty of cups and glasses in the cupboards, all too dirty to use.

“I’m sorry, this is just unacceptable,” Mel said loudly.

“It’s a little dirt is all.”

“There’s a bird’s nest in the oven!” Mel exclaimed, completely beside herself.

Mrs. McCrea clomped into the kitchen in her muddy rubber boots, reached into the open oven door and plucked out the bird’s nest. She went to the front door and pitched it out into the yard. She shoved her glasses up on her nose as she regarded Mel. “No more bird’s nest,” she said in a voice that suggested Mel was trying her patience.

“Look, I’m not sure I’d make it. That old man in the pickup had to pull me out of the mud just down the road. I can’t stay here, Mrs. McCrea—it’s out of the question. Plus, I’m starving and I don’t have any food with me.” She laughed hollowly. “You said there would be adequate housing ready for me, and I took you to mean clean and stocked with enough food to get me through a couple of days till I could shop for myself. But this—”

“You have a contract,” Mrs. McCrea pointed out.

“So do you,” Mel said. “I don’t think you could get anyone to agree this is adequate or ready.”

Hope looked up. “It’s not leaking, that’s a good sign.”

“Not quite good enough, I’m afraid.”

“That damned Cheryl Creighton was supposed to be down here to give it a good cleaning, but she had excuses three days in a row. Been drinking again is my guess. I got some bedding in the truck and I’ll take you to get dinner. It’ll look better in the morning.”

“Isn’t there some place else I can stay tonight? A bed-and-breakfast? A motel on the highway?”

“Bed-and-breakfast?” she asked with a laugh. “This look like a tourist spot to you? The highway’s an hour off and this is no ordinary rain. I have a big house with no room in it—filled to the top with junk. They’re gonna light a match to it when I die. It would take all night to clear off the couch.”

“There must be something…”

“Nearest thing is Jo Ellen’s place—she’s got a nice spare room over the garage she lets out sometimes. But you wouldn’t want to stay there. That husband of hers can be a handful. He’s been slapped down by more than one woman in Virgin River—and it’d be a bad thing, you in your nightie, Jo Ellen sound asleep and him getting ideas. He’s a groper, that one.”

Oh, God, Mel thought. Every second this place sounded worse and worse.

“Tell you what we’ll do, girl. I’ll light the hot water heater, turn on the refrigerator and heater, then we’ll go get a hot meal.”

“At the Pie and Coffee shop?”

“That place closed down three years back,” she said.

“But you sent me a picture of it—like it was where I’d be getting lunch or dinner for the next year!”

“Details. Lord, you do get yourself worked up.”

“Worked up!?”

“Go jump in the truck and I’ll be right along,” she commanded. Then ignoring Mel completely, she went to the refrigerator and stooped to plug it in. The light went on immediately and Mrs. McCrea reached inside to adjust the temperature and close the door. The refrigerator’s motor made an unhealthy grinding sound as it fired up.

Mel went to the Suburban as she’d been told, but it was so high off the ground she found herself grabbing the inside of the open door and nearly crawling inside. She felt a lot safer here than in the house where her hostess would be lighting a gas water heater. She had a passing thought that if it blew up and destroyed the cabin, they could cut their loses here and now.

Once in the passenger seat, she looked over her shoulder to see the back of the Suburban was full of pillows, blankets and boxes. Supplies for the falling-down house, she assumed. Well, if she couldn’t get out of here tonight, she could sleep in her car if she had to. She wouldn’t freeze to death with all those blankets. But then, at first light…

A few minutes passed and then Mrs. McCrea came out of the cottage and pulled the door closed. No locking up. Mel was impressed by the agility with which the old woman got herself into the Suburban. She put a foot on the step, grabbed the handle above the door with one hand, the armrest with the other and bounced herself right into the seat. She had a rather large pillow to sit on and her seat was pushed way up so she could reach the pedals. Without a word, she put the vehicle in gear and expertly backed down the narrow drive out onto the road.

“When we talked a couple weeks ago, you said you were pretty tough,” Mrs. McCrea reminded her.

“I am. I’ve been in charge of a women’s wing at a three-thousand-bed county hospital for the past two years. We got all the most challenging cases and hopeless patients, and did a damn fine job if I do say so myself. Before that, I spent years in the emergency room in downtown L.A., a very tough place by anyone’s standards. By tough, I thought you meant medically. I didn’t know you meant I should be an experienced frontier woman.”

“Lord, you do go on. You’ll feel better after some food.”

“I hope so,” Mel replied. But, inside she was saying, I can’t stay here. This was crazy, I’m admitting it and getting the hell out of here. The only thing she really dreaded was owning up to Joey.

They didn’t talk during the drive. In Mel’s mind there wasn’t much to say. Plus, she was fascinated by the ease, speed and finesse with which Ms. McCrea handled the big Suburban, bouncing down the tree-lined road and around the tight curves in the pouring rain.

She had thought this might be a respite from pain and loneliness and fear. A relief from the stress of patients who were either the perpetrators or victims of crimes, or devastatingly poor and without resources or hope. When she saw the pictures of the cute little town, it was easy to imagine a homey place where people needed her. She saw herself blooming under the grateful thanks of rosy-cheeked country patients. Meaningful work was the one thing that had always cut through any troubling personal issues. Not to mention the lift of escaping the smog and traffic and getting back to nature in the pristine beauty of the forest. She just never thought she’d be getting this far back to nature.

The prospect of delivering babies for mostly uninsured women in rural Virgin River had closed the deal. Working as a nurse practitioner was satisfying, but midwifery was her true calling.

Joey was her only family now; she wanted Mel to come to Colorado Springs and stay with her, her husband Bill and their three children. But Mel hadn’t wanted to trade one city for another, even though Colorado Springs was considerably smaller. Now, in the absence of any better ideas, she would be forced to look for work there.

As they passed through what seemed to be a town, she grimaced again. “Is this the town? Because this wasn’t in the pictures you sent me, either.”

“Virgin River,” she said. “Such as it is. Looks a lot better in daylight, that’s for sure. Damn, this is a big rain. March always brings us this nasty weather. That’s the doc’s house there, where he sees patients when they come to him. He makes a lot of house calls, too. The library,” she pointed. “Open Tuesdays.”

They passed a pleasant-looking steepled church, which appeared to be boarded up, but at least she recognized it. There was the store, much older and more worn, the proprietor just locking the front door for the night. A dozen houses lined the street—small and old. “Where’s the schoolhouse?” Mel asked.

“What schoolhouse?” Mrs. McCrea countered.

“The one in the picture you sent to the recruiter.”

“Hmm. Can’t imagine where I got that. We don’t have a school. Yet.”

“God,” Mel groaned.

The street was wide, but dark and vacant—there were no streetlights. The old woman must have gone through one of her ancient photo albums to come up with the pictures. Or maybe she snapped a few of another town.

Across the street from the doctor’s house Mrs. McCrea pulled up to the front of what looked like a large cabin with a wide porch and big yard, but the neon sign in the window that said Open clued her in to the fact that it was a tavern or café. “Come on,” Mrs. McCrea said. “Let’s warm up your belly and your mood.”

“Thank you,” Mel said, trying to be polite. She was starving and didn’t want an attitude to cost her her dinner, though she wasn’t optimistic that anything but her stomach would be warm. She looked at her watch. Seven o’clock.

Mrs. McCrea shook out her slicker on the porch before going in, but Mel wasn’t wearing a raincoat. Nor did she have an umbrella. Her jacket was now drenched and she smelled like wet sheep.

Once inside, she was rather pleasantly surprised. It was dark and woody with a fire ablaze in a big stone hearth. The polished wood floors were shiny clean and something smelled good, edible. Over a long bar, above rows of shelved liquor bottles, was a huge mounted fish; on another wall, a bearskin so big it covered half the wall. Over the door, a stag’s head. Whew. A hunting lodge? There were about a dozen tables sans tablecloths and only one customer at the bar; the old man who had pulled her out of the mud sat slumped over a drink.

Behind the bar stood a tall man in a plaid shirt with sleeves rolled up, polishing a glass with a towel. He looked to be in his late thirties and wore his brown hair cropped close. He lifted expressive brows and his chin in greeting as they entered. Then his lips curved in a smile.

“Sit here,” Hope McCrea said, indicating a table near the fire. “I’ll get you something.”

Mel took off her coat and hung it over the chair back near the fire to dry. She warmed herself, vigorously rubbing her icy hands together in front of the flames. This was more what she had expected—a cozy, clean cabin, a blazing fire, a meal ready on the stove. She could do without the dead animals, but this is what you get in hunting country.

“Here,” the old woman said, pressing a small glass of amber liquid into her hand. “This’ll warm you up. Jack’s got some stew on the stove and bread in the warmer. We’ll fix you up.”

“What is it?” she asked.

“Brandy. You gonna be able to get that down?”

“Damn right,” she said, taking a grateful sip and feeling it burn its way down to her empty belly. She let her eyes drift closed for a moment, appreciating the unexpected fine quality. She looked back at the bar, but the bartender had disappeared. “That guy,” she finally said, indicating the only customer. “He pulled me out of the ditch.”

“Doc Mullins,” she explained. “You might as well meet him right now, if you’re okay to leave the fire.”

“Why bother?” Mel said. “I told you—I’m not staying.”

“Fine,” the old woman said tiredly. “Then you can say hello and goodbye all at once. Come on.” She turned and walked toward the old doctor and with a weary sigh, Mel followed. “Doc, this is Melinda Monroe, in case you didn’t catch the name before. Miss Monroe, meet Doc Mullins.”

He looked up from his drink with rheumy eyes and regarded her, but his arthritic hands never left his glass. He gave another single nod.

“Thanks again,” Mel said. “For pulling me out.”

The old doctor gave a nod, looking back to his drink.

So much for the friendly small-town atmosphere, she thought. Mrs. McCrea was walking back to the fireplace. She plunked herself down at the table.

“Excuse me,” Mel said to the doctor. He turned his gaze toward her, but his bushy white brows were drawn together in a definite scowl, peering over the top of his glasses. His white hair was so thin over his freckled scalp that it almost appeared he had more hair on his brows than his head. “Pleasure to meet you. So, you wanted help up here?” He just seemed to glare at her. “You didn’t want help? Which is it?”

“I don’t much need any help,” he told her gruffly. “But that old woman’s been trying to get a doc to replace me for years. She’s driven.”

“And why is that?” Mel bravely asked.

“Couldn’t imagine.” He looked back into his glass. “Maybe she just doesn’t like me. Since I don’t like her that much, makes no difference.”

The bartender, and presumably proprietor, was carrying a steaming bowl out of the back, but he paused at the end of the bar and watched as Mel conversed with the old doctor.

“Well, no worries, mate,” Mel responded, “I’m not staying. It was grossly misrepresented. I’ll be leaving in the morning, as soon as the rain lets up.”

“Wasted your time, did you?” he asked, not looking at her.

“Apparently. It’s bad enough the place isn’t what I was told it would be, but how about the complication that you have no use for a practitioner or midwife?”

“There you go,” he said.

Mel sighed. She hoped she could find a decent job in Colorado.

A young man, a teenager, brought a rack of glasses from the kitchen into the bar. He sported much the same look as the bartender with his short cropped, thick brown hair, flannel shirt and jeans. Handsome kid, she thought, taking in his strong jaw, straight nose, heavy brows. As he was about to put the rack under the bar, he stopped short, staring at Mel in surprise. His eyes grew wide; his mouth dropped open for a second. She tilted her head slightly and treated him to a smile. He closed his mouth slowly, but stood frozen, holding the glasses.

Mel turned away from the boy and the doctor. She headed for Mrs. McCrea’s table. The bartender set down a bowl along with a napkin and utensils, then stood there awaiting her. He held the chair for her. Close up, she saw how big a guy he was—over six feet and broad-shouldered. “Miserable weather for your first night in Virgin River,” he said pleasantly.

“Miss Melinda Monroe, this is Jack Sheridan. Jack, Miss Monroe.”

Mel felt the urge to correct them—tell them it was Mrs. But she didn’t because she didn’t want to explain that there was no longer a Mr. Monroe, a Dr. Monroe in fact. So she said, “Pleased to meet you. Thank you,” she added, accepting the stew.

“This is a beautiful place, when the weather cooperates,” he said.

“I’m sure it is,” she muttered, not looking at him.

“You should give it a day or two,” he suggested.

She dipped her spoon into the stew and gave it a taste. He hovered near the table for a moment. Then she looked up at him and said in some surprise, “This is delicious.”

“Squirrel,” he said.

She choked.

“Just kidding,” he said, grinning at her. “Beef. Corn fed.”

“Forgive me if my sense of humor is a bit off,” she replied irritably. “It’s been a long and rather arduous day.”

“Has it now?” he said. “Good thing I got the cork out of the Remy, then.” He went back behind the bar and she looked over her shoulder at him. He seemed to confer briefly and quietly with the young man, who continued to stare at her. His son, Mel decided.

“I don’t know that you have to be quite so pissy,” Mrs. McCrea said. “I didn’t sense any of this attitude when we talked on the phone.” She dug into her purse and pulled out a pack of cigarettes. She shook one out and lit it—this explained the gravelly voice.

“Do you have to smoke?” Mel asked her.

“Unfortunately, I do,” Mrs. McCrea said, taking a long drag.

Mel just shook her head in frustration. She held her tongue. It was settled, she was leaving in the morning and would have to sleep in the car, so why exacerbate things by continuing to complain? Hope McCrea had certainly gotten the message by now. Mel ate the delicious stew, sipped the brandy, and felt a bit more secure once her belly was full and her head a tad light. There, she thought. That is better. I can make it through the night in this dump. God knows, I’ve been through worse.

It had been nine months since her husband, Mark, had stopped off at a convenience store after working a long night shift in the emergency room. He had wanted milk for his cereal. But what he got was three bullets, point-blank to the chest, killing him instantly. There had been a robbery in progress, right in a store he and Mel dropped into at least three times a week. It had ended the life she loved.

Spending the night in her car, in the rain, would be nothing by comparison.

***

Jack delivered a second Remy Martin to Miss Monroe, but she had declined a second serving of stew. He stayed behind the bar while she ate, drank and seemed to glower at Hope as she smoked. It caused him to chuckle to himself. The girl had a little spirit. What she also had was looks. Petite, blond, flashing blue eyes, a small heart-shaped mouth, and a backside in a pair of jeans that was just awesome. When the women left, he said to Doc Mullins, “Thanks a lot. You could have cut the girl some slack. We haven’t had anything pretty to look at around here since Bradley’s old golden retriever died last fall.”

“Humph,” the doctor said.

Ricky came behind the bar and stood next to Jack. “Yeah,” he heartily agreed. “Holy God, Doc. What’s the matter with you? Can’t you think of the rest of us sometimes?”

“Down boy,” Jack laughed, draping an arm over his shoulders. “She’s outta your league.”

“Yeah? She’s outta yours, too,” Rick said, grinning.

“You can shove off anytime. There isn’t going to be anyone out tonight,” Jack told Rick. “Take a little of that stew home to your grandma.”

“Yeah, thanks,” he said. “See you tomorrow.”

When Rick had gone, Jack hovered over Doc and said, “If you had a little help, you could do more fishing.”

“Don’t need help, thanks,” he said.

“Oh, there’s that again,” Jack said with a smile. Any suggestion Hope had made of getting Doc some help was stubbornly rebuffed. Doc might be the most obstinate and pigheaded man in town. He was also old, arthritic and seemed to be slowing down more each year.

“Hit me again,” the doctor said.

“I thought we had a deal,” Jack said.

“Half, then. This goddamn rain is killing me. My bones are cold.” He looked up at Jack. “I did pull that little strumpet out of the ditch in the freezing rain.”

“She’s probably not a strumpet,” Jack said. “I could never be that lucky.” Jack tipped the bottle of bourbon over the old man’s glass and gave him a shot. But then he put the bottle on the shelf. It was his habit to look out for Doc and left unchecked, he might have a bit too much. He didn’t feel like going out in the rain to be sure Doc got across the street all right. Doc didn’t keep a supply at home, doing his drinking only at Jack’s, which kept it under control.

Couldn’t blame the old boy—he was overworked and lonely. Not to mention prickly.

“You could’ve offered the girl a warm place to sleep,” Jack said. “It’s pretty clear Hope didn’t get that old cabin straight for her.”

“Don’t feel up to company,” he said. Then Doc lifted his gaze to Jack’s face. “Seems you’re more interested than me, anyway.”

“Didn’t really look like she’d trust anyone around here at the moment,” Jack said. “Cute little thing, though, huh?”

“Can’t say I noticed,” he said. He took a sip and then said, “Didn’t look like she had the muscle for the job, anyway.”

Jack laughed, “Thought you didn’t notice?” But he had noticed. She was maybe five-three. Hundred and ten pounds. Soft, curling blond hair that, when damp, curled even more. Eyes that could go from kind of sad to feisty in an instant. He enjoyed that little spark when she had snapped at him that she didn’t feel particularly humorous. And when she took on Doc, there was a light that suggested she could handle all kinds of things just fine. But the best part was that mouth—that little pink heart-shaped mouth. Or maybe it was the bottom.

“Yeah,” Jack said. “You could’ve cut a guy a break and been a little friendlier. Improve the scenery around here.