Читать книгу Deeper into the Darkness - Rod MacDonald - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

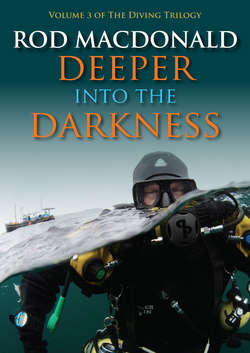

4 HMS HAMPSHIRE

ОглавлениеExplorers Club Flag #192 expedition on the 100th anniversary of its sinking

Notwithstanding that diving had been forbidden on the wreck of the Hampshire since 2002, in 2015 I was approached by Paul Haynes, and by Emily Turton and Ben Wade, the owners and skippers of the fine Scapa Flow dive boat, MV Huskyan. They had an idea about mounting an expedition to survey the wreck on 5 June 2016, the 100th anniversary of its loss. As I had previously worked my way through the corridors of power in 1997 and 2000 to get permission from the MOD to dive the wreck, they wondered if I would take on the role of expedition leader and make an application to the UK Secretary of State for Defence for a licence to dive the wreck.

At this point, I had thought since 2002 that I would never dive this particular wreck again. But the more I thought how historically important a wreck it was, the more I thought that it would be absolutely fitting to record the wreck for posterity at this important anniversary. Wrecks from both wars are now rapidly falling apart – it would never be in as good a condition again. We could record the wreck in detail as it was just now – information that would be made available for the public good and posterity.

On balance, I thought it was a great idea and agreed to take on the position of expedition leader. Paul Haynes, with his military and diving safety background would be the diving safety officer. Via a number of Skype video calls we agreed that a two-week expedition would be required to guarantee getting the results we wanted as it was foreseeable, given the exposed wreck site, that we could be blown out for 3–4 days. Sitting out to the north-west of Orkney, there is nothing for thousands of miles to the west until America, and great Atlantic gales and storms regularly sweep in from the west. We reviewed the tidal projections and thrashed out a mission plan: what results we wanted and how we would get them.

Armed with this rough framework, I contacted the authorities with the idea – more in hope than expectation. All my old MOD contacts from 1997 and 2000 were now gone, but I was passed on, and to my surprise I was told that the expedition plan was acceptable to them and that Navy Sec-3rd Sector would deal with the licence application. They naturally wanted to know who would be in the team, our backgrounds, the expedition aims, diving methodology and what new technology we would bring to recording the wreck. But in principle, if we could satisfy them in more detail, a licence would be granted.

With the first hurdle cleared, the four co-organisers then had to sit down and agree who would be invited to join the team. There would be 12 divers – and in addition to being seasoned deep mixed-gas rebreather divers, each would have to bring a specialist skill to the group to help us achieve our aims. There could be no passengers.

After throwing a lot of names into the hat we came up with a dream team of divers that we would like on the exped. There would be no massive egos, no difficult, abrasive, grand standing or needy characters – just good solid, safe, deep divers, each with a particular skill. It’s fair to say that we ended up with at least two or three names for each of the slots.

We talked over our list of potential divers and whittled it down until we had a final group. The invitations went out, and aside from a couple of divers who couldn’t make it due to work commitments, everyone else we asked jumped at the chance of being on such an expedition. The final expedition team pool was:

1. Rod Macdonald, expedition leader

2. Paul Haynes, diving safety officer

3. Emily Turton, expedition organiser, stills photography lighting support

4. Ben Wade, expedition organiser, survey diver and videographer

5. Brian Burnett, survey diver and videographer

6. Prof. Chris Rowland, survey diver and 3D imaging support

7. Gary Petrie, survey diver and diving support

8. Greg Booth, survey diver and diving support

9. Immi Wallin, survey diver and 3D photogrammetry imaging

10. Prof. Kari Hyttinen, survey diver and 3D photogrammetry imaging

11. Marjo Tynkkynen, survey diver and stills photography

12. Mick Watson, survey diver and diving support

13. Paul Toomer, survey diver and diving support.

A further chain of emails with Navy Sec-3rd Sector resulted in the Navy’s legal department sending me a draft licence from the Secretary of State for Defence for approval. The draft licence was adjusted between us and approved – and then went for signature. A change in the legal team at the MOD however resulted in a tense wait, as the new legal team wanted to review what their predecessors had done before signing off. Could the expedition be killed at the very last moment? Thankfully the new team were happy to proceed.

After their review was completed, the signed Licence Ref No C/001/2016 was sent to me, granted under Section 4 of the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986. As expedition leader, I was appointed sole licensee and authorised, subject to conditions, to conduct a visual survey of the wreck over a specified period of 30 days between 30 May 2016 and 1 August 2016. The 30-day period straddled the actual day of the 100th anniversary – 5 June 2016 – and it was made clear to us that diving operations could not be conducted on 5 June itself as there would be a Royal Navy warship above the wreck for a wreath-laying remembrance ceremony.

A number of very reasonable conditions were imposed by the licence. The team must not:

a) recover any artefacts from the wreck site

b) tamper with, damage, move, remove or unearth any human remains

c) film or photograph any human remains

d) enter any hatch or other opening in the wreck.

It was also provided that although any film or photographic material taken during the dives would remain the property of me as licensee, it could not be used for any commercial purposes without the prior approval of the licence signatory, the military authorities.

Having received the licence, we fixed the dates for the two-week exped and reserved the Huskyan for the duration of the expedition. We then got around to sending out formal invitations and the necessary paperwork about insurance, liability and diving methodology to the selected divers.

Our general goal was to make this expedition the most advanced survey of a British warship that had ever been carried out. To achieve this we would be adopting and utilising the rapid advances that are currently being made in the development of underwater imaging technology and in particular 3D photogrammetry and virtual reality (VR). Specialist highresolution video cameras would be used to capture suitable footage for the photogrammetry and VR, the video camera operator using two LED 100W video lights and a single LED 1000W specialist video light. The camera operator would be supported by two lighting assistants, each of whom would carry a 300W video light. 100W is roughly 10,000 lumens so in total 180,000 lumens would be used to capture the photogrammetry and VR footage.

In photogrammetry, the camera operator very slowly pans over sections of the wreck or an individual object. Each one of the hundreds of frames that make up the moving picture images would be taken from a slightly different angle. Once the underwater imagery was downloaded topside into powerful laptops, specialist computer software takes frame captures from the video footage and produces a basic point cloud within a few hours of processing. The point cloud image of the wreck begins to appear on the screen as literally thousands of points – but as the processing goes on, the points become more defined and the shape of the wreck begins to appear. Further computer processing of the point cloud raw data is then carried out whereby the software triangulates between recognisable points of data in each frame and is able to refine the raw image to give a lifelike 3D image that a viewer can ‘fly’ around on a computer and explore in detail. We aimed to make the 3D photogrammetry model available online for the public good so that maritime archaeologists, historians and other interested folk can study it in detail in the future, without having to physically dive it. I will be interested to see what information can be brought out by such specialists from our work in due course.

Going beyond 3D photogrammetry, we also planned to render the whole wreck on a 1:1 aspect ratio, that is at full size, in virtual reality. By putting on VR goggles, viewers would be immersed in the water, standing or floating beside a life-size image of the wreck. The wreck would tower some 50 feet above you from the seabed. Our plans were nothing if not ambitious.

In addition to photogrammetry and VR, hundreds of high-resolution underwater photographs would be taken and we would blitz the wreck with video cameras, getting as much imagery as we could of this never-to-be-repeated opportunity. We expected that some 100 hours of video footage on the wreck would be taken.

As we began to get going, sorting out the full logistics of the expedition, we began to get a distinct feeling that we were representing our sport, and that the expedition and our results would be closely studied from a number of angles. We believed that with our technical diving abilities and the underwater visualisation techniques we were employing, if we did a good job, the military authorities might realise just how good modern diving and underwater imaging techniques were. We hoped to bring results that the military themselves could not achieve – believing that this might open a door for better cooperation between military authorities and civilian divers on other projects.

There was little imagery of the wreck in existence before our expedition – just a few grainy still photographs of objects and a few bits of shaky underwater footage. Although I had dived the wreck several times in 1997 and 2000, anything could have happened to it since then. The current condition of the wreck was unknown – it was possible that it had totally collapsed.

We formalised the aims of the Hampshire 2016 Expedition as being:

1. To ascertain the present condition of the wreck

2. To undertake a detailed survey

3. To compile an extensive catalogue of stills and video imagery

4. To produce a survey expedition report for future historical reference

5. To raise public awareness of the historical significance of the sinking

6. To foster positive relations with government and shipwreck heritage bodies.

The Explorers Club is based in New York and is a multi-discipline club dedicated to promoting and encouraging exploration in all aspects. I was inducted into it in 2015 for my work with shipwrecks.

It was founded in 1905, and its members have a number of illustrious firsts in exploration. Robert Peary was a member when he was first to the North Pole in 1909. Roald Amundsen, was a member when he was first to the South Pole in 1911. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, first to the moon in 1969. Sir Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tensing Norgay, first to the summit of Everest were members, Thor Heyerdahl in Kontiki – the list of firsts for members goes on and on.

At The Explorers Club HQ in New York, there is a humble granite plaque which reads:

WORLD CENTER FOR EXPLORATION

| First to the North Pole | 1909 |

| First to the South Pole | 1911 |

| First to the summit of Mt Everest | 1953 |

| First to the deepest point in the ocean | 1960 |

| First to the surface of the Moon | 1969 |

Underneath the last entry there is a space – waiting for the first manned Mars landing.

Since 1918, whenever the Explorers Club believes that an expedition is going to be of scientific or special merit it awards an Explorers Club flag, which is then carried on the expedition. There are some 220 flags in total, and the flags are reused on successive expeditions in the field. Explorers Club flags have been carried to all the earth’s continents, as well as to the deepest parts of the sea and the highest places on the land – and to the moon.

As at the date of my expedition, 850 explorers had carried the flag on 1,450 expeditions. A select few of the 222 flags have been retired and framed for display at the Club House in New York. These include the flags carried by Thor Heyerdahl on his raft Kontiki as he sailed across the Pacific, and the miniature flags carried aboard Apollo 8 and 15. Some special flags are of particular historic importance, such as the flag carried aboard Apollo 11 by Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to the surface of the moon.

The Explorers Club declared our Hampshire expedition to be a Flagged Expedition due to the historic importance of the shipwreck – and two weeks before the expedition was due to begin, an airmail package arrived with Flag #192 and the paperwork to go along with it, which included a list of the previous expeditions this very flag had been carried on.

| Amos Burg | 1968 Alaska Rivers Expedition |

| Dr. George V.B. Cochran | 1974 North Baffin-Bylot Expedition |

| Dr. George V.B. Cochran | 1972 Baffinland Arctic-Alpine Expedition |

| Dr. George V.B. Cochran | 1973 Baffin-Kingnait Expedition |

| Peter Byrne | 1975 Nepal Himalayan – Terai Mammals |

| Ralph Lenton | 1970 Mt Ararat Expedition |

| Dr. I. Drummond Rennie | 1973 American Dhaulagiri Expedition |

| William Isherwood | 1971 Glaciological Survey |

| Bob Sparks | 1975 Trans-Atlantic Solo Balloon Crossing |

| Bob Sparks | 1976 Trans-Atlantic Balloon Flight. |

The flag had been lost on expedition in the late 1970s – but had recently been found and returned to the Explorers Club shortly before my expedition. After a break of some 40 years, it was going on expedition again.

Our dates were now set in stone – and with all the acceptances now in from our team, we now had major commitments being made. Paul Haynes, in his capacity of dive safety officer, created a thorough 40-page Dive Brief, and this was emailed out to all the team members six months before the exped. This covered the basics of our planned diving methodology, such as the standardisation of rebreather trimix diluent gas of 15/50 across the team. This provided an oxygen partial pressure (PO2) of 1.2 bar at the deepest depth anticipated of 70 metres, and facilitated an effective rebreather diluent flush without the safety implications of using a ‘lean’ hypoxic gas, where a diver could black out. At the maximum depth of 70 metres, this trimix mixture would give divers an equivalent narcotic depth (END) of 25 metres. This means that at 70 metres the divers would only be experiencing the same nitrogen narcosis as a diver diving on air at 25 metres, next to negligible.

Each diver had to carry sufficient open-circuit bailout gas to independently support a full open-circuit decompression profile in the event of a catastrophic failure of the primary life support rebreather. As a minimum, divers were required to carry an 11-litre cylinder of bailout 15/50 bottom gas under their left arm and an 11-litre cylinder of EAN 60 deco gas on their right side.

A diver tag in/out system was used for all dives during the expedition with named tags for all divers being supplied. The tags were clipped to a brass ring where the transfer line from the trapeze connected into the fixed downline. (Author’s collection )

We would be using a decompression trapeze with horizontal bars at 6, 9 and 12 metres, and ropes leading up at either side to two large red buoys that would float it. We intended to lay two fixed downlines, one at the bow of the wreck and one at the stern. The trapeze would be secured to the bow or stern downline by a transfer line on a daily basis. Extra cylinders of bailout gas would be clipped to the downline and the trapeze in case of emergency.

A diver ‘down / up’ logging system using named tags was employed to monitor who had left bottom and ascended to the trapeze. Each diver was given a stainless steel shackle with a colour-coded plastic name tag on it, with their name. Individual divers clipped their named tags to a brass ring in the transfer line at a depth of 30 metres on the descent. Divers would remove their tag from the ring as they ascended at the end of the dive and moved along the transfer line to the trapeze for decompression. The last diving pair ascending would disconnect the trapeze from the downline before continuing their ascent up the trapeze transfer line. All 12 divers would then begin to drift with the current, which would be picking up as slack water passed, as they slowly ascended through the various levels of their decompression stops.

Once all 12 divers were on the trapeze and we had disconnected and begun to drift, the procedure would be that a single 6-foot-tall red delayed surface marker buoy (DSMB) would be sent up. If for any reason there was a separation event, and divers failed to return to the downline, the team would wait 20 minutes to give the lost divers a chance of finding their way back to the downline. If the divers had not arrived at the deco station by that time, the trapeze would be disconnected from the downline. With the tide picking up after slack water, it would be impossible for all the divers to carry out two hours of decompression stops with the trapeze still connected to the downline. It would be swept horizontal and possibly up to the surface. Once the trapeze was unclipped and was drifting with the current, the divers would feel that they were in comfortable stationary water – even though the whole mass of water they were suspended in was racing across the seabed at 1–2 knots.

If we had to disconnect with divers still on the wreck or doing a free ascent away from the downline, then we would send up a yellow DSMB. That would be the signal to the skipper topside that there had been a separation event and that he should keep his eyes peeled for DSMBs from free-drifting divers. With such a group of seasoned deep divers, each had lots of experience of carrying out free ascents under their own DSMB. It wouldn’t be an alarming situation; we just wanted a way of telling the skipper topside that divers were separated and that he should look out for their DSMBs, as well as following the trapeze.

To keep the divers together in a loose single group on the trapeze for deco, we restricted bottom time to 35 minutes.

All divers were required to carry a minimum of one red DSMB with their first name or initials written in large black letters on the top of it, together with a whistle, hi-vis flag and yellow DSMB for emergency signalling. This was no place to be separated from the dive boat and not be seen.

The team would arrive in Orkney on Saturday 28 May and load kit onto the Huskyan, and once everyone was sorted out with cylinders filled and analysed, scrubbers filled with sofnalime, rebreathers all prepped and set up, we would have a briefing that night. Diving would start the next day, Sunday 29 May, with two shakedown dives on the deepest German World War I battleship in Scapa Flow, the upturned SMS Markgraf in 45 metres. The early morning dive would be a simple personal shakedown dive to reveal any problems that might have occurred in transit and so that people could make sure they were happy with their kit. The afternoon dive would be a full dress-rehearsal, deploying the trapeze, adding the extra bailout cylinders and everyone transferring from the wreck to it for disconnection from the downline and a free-drifting decompression.

Throughout Saturday 28 May 2016, our group of deep shipwreck divers began to arrive in Stromness from all points of the compass. The group consisted of ten British and three Finnish divers, many of whom had been travelling for days by road, sea and air to get here. The Finns, Marjo Tynkkynen, Kari Hyttinen and Immi Wallin, in particular brought highly specialist underwater stills and 3D photogrammetry expertise to the expedition, and collectively there was over 200 years of worldwide wreck diving experience between the group. However, despite the high level of technical diving and shipwreck knowledge, at this point many of the group had never met each other, let alone dived together before. Shaping this group of divers into a safe and effective deep shipwreck survey team would be the first expedition objective.

That night, the four co-organisers hosted a team briefing in our accommodation, the fine Divers Lodge owned by Ben and Emily. As expedition leader, it fell to me to give the welcoming address and expedition overview, including the legal restrictions by which we were bound. We felt it would be too much to brief on the wreck straight away on this, our first gathering, so we had decided to restrict this meeting to the basics and let everyone get to know each other. The wreck briefing itself would be done tomorrow after the shakedown dives on the Markgraf were completed.

To build upon the detailed expedition diving plan previously issued to all divers, my introduction was followed by a safety brief by Paul Haynes, wearing his hat as diving safety officer, the purpose being to instil an expedition diving safety culture from the very outset. This included confirming the safety policy, stating the expedition organisers’ expectations, defining roles and responsibilities, and confirming the diving methodology, safety procedures and emergency protocols to be adhered to.

We wanted to stress that this was not a diving holiday – we were here to do a job. I emphasised to the team that the process of actually getting our licence had probably taken me about 20 months and it seemed unlikely that a licence would ever be granted again. We felt that a number of government bodies would be paying close attention to the expedition, our conduct and our results. We were representing our sport and if we did it right, other doors might open in the future for divers.

The HMS HampshireExplorers Club Flag No 192 expedition team in front of the starboard propeller of Hampshire at Lyness. The author (right) and Paul Haynes (left) hold the Explorers Club flag.

Left to right, back row: Ross Dowrie (crew), Russ Evans (skipper), Kevin Heath, Ben Wade, Brian Burnett, MarjoTynkkynen, Kari Hyttinen, Mic Watson.

Front row: Paul Toomer, Gary Petrie, ImmiWallin, Emily Turton, Paul Haynes, Rod Macdonald, Greg Booth, Chris Rowland. © MarjoTynkkynen

The next day, Sunday, was time for the full dress-rehearsal to confirm personal equipment functionality. This was no ordinary warm-up dive however – some divers in the team had never been to Scapa Flow before, and this was a chance to see first-hand one of the König- class battleships that fired at British Grand Fleet warships during the Battle of Jutland on 30 May/1 June 1916. It was a fitting start to the expedition, and helped shape the team’s historical understanding of events leading up to the loss of Hampshire.

The first dive was uneventful, and following a suitable surface interval, a full team dive rehearsal was next. There was no time to explore Markgraf further; the afternoon was to be a carefully choreographed procedures dive. This included decompression station deployment, additional bailout gas staging, diver tagging procedures, simulated drifting decompression stops, emergency drop gas signalling and deployment, unconscious diver recovery, basic life support, oxygen administration and coastguard evacuation protocols – a very busy afternoon indeed.

With a limited window of opportunity to dive HMS Hampshire, spending a full day diving in the Flow with a group of such experienced divers, some of whom were technical diving instructor trainers and examiners, may have appeared unnecessary. But we felt that a group of divers is not necessarily a team – and the safe and efficient running of the expedition would be reliant on everyone aboard knowing their roles and responsibilities, the safety procedures and emergency protocols. The only way of truly confirming the operational viability of any procedure is to run through it in practice in the form of a real-time dress rehearsal. By the end of the day, everyone agreed that it was only at that point that we were collectively prepared and ready to turn west into the open Atlantic and safely start the expedition proper.

With the shakedown dives now safely behind us, we met again that night and I ran over what I knew about the ship from a historical perspective and what I knew about the wreck from my own knowledge gained from diving it a number of times 15–20 years previously, before it was closed off to divers.

As it was such a large site to survey, the team objective for the first dive was to gain a general orientation and appreciation of the site. Once we collectively had a feel for the lay of the site, individual survey tasks would then be allocated to each dive pair on a daily basis.

The next day, full of enthusiasm, we all rose at 0600, and after breakfast in the Divers Lodge, walked across the quay to the Huskyan, whose twin diesels were already turning over. We were soon all aboard, ropes were cast off and we were away – heading south out of Stromness harbour before turning to the west to head out through Hoy Sound to the Atlantic.

Once out of Scapa Flow, we turned our head to the north and started to run up the west coast of Orkney, retracing the route taken by the Hampshire 100 years earlier. Slack water would arrive about 1130, so we would be arriving on site well in advance of slack, ready to safely place a weighted shotline on the seabed beside the wreck, kit up and be ready to dive at slack – as I said before, you can never be too early for slack.

The passage up the west coast was beautiful on this first day. It was sunny, with little wind and the water seemed relatively smooth; it was however a little deceptive, as a languid Atlantic swell was still rolling in gently from the north-west, the boat slowly rising and falling a few metres as the swell passed beneath us.

As we arrived on site, we soon picked up the wreck on the echo sounder. The tall Kitchener Memorial Tower stood prominently just 1.5 miles away on the high cliffs of Marwick Head – very poignantly reminding us of the tragedy that had occurred in this very spot 100 years almost to the day.

We were aware from previous visits that the wreck lay in a roughly north-west/south-east attitude, with her bow to the north. We had decided that the first day’s shot would be dropped on the seabed just off the stern, which was the most intact area.

The shotline would be floated initially with just a few rigid round fishermen’s floats. As it was still an hour or two to go until slack water, we knew that these would be swept under by the tide – that was the idea – they would rise again as the tide dropped off towards slack water, an easy visual indicator of what was happening. If we had stuck a big danbuoy on the downline it would have remained on the surface, but likely would have been dragged down current by the tide, dragging the shot away from the wreck. There was no room for error.

Paul Haynes was excellent in his role as diving safety officer, a role he has played many times, in both civilian and military expeditions. He had the trapeze completely sorted out and rigged to self-deploy using his old parachuting knowledge.

The four expedition co-organisers had already divided the team into suitable dive pairs. Each pair had one diver who had a key role such as videography, stills photography, 3D photogrammetry etc., with the other supporting. Some of the pairings had been easy and natural – the well-known Finnish photojournalist Marjo Tynkkynen had been resident in Orkney for some time, diving with skipper Emily Turton off Huskyan. They knew and understood how each other dived and naturally fell to dive together, with Emily as lighting assistant and model for Marjo to shoot. Marjo’s hi-res stills would be captured using a Canon 5DmkII camera in a Subal housing with 16-35mm LII and Sigma 15mm lenses. The camera strobes were Canon Speedlite 580exll. To light up larger sections of the wreck, two additional 300W LED Scubamafia Beast video lights were deployed by support divers.

Kari Hyttinen and Immi Wallin from Finland had worked together with 3D photogrammetry on a number of high-profile wrecks around the world, and so were another natural pairing.

To avoid congestion of the changing areas and the dive deck, to marshal all 12 divers, we subdivided them into two teams of six. Team 1 would get dressed in their thermal undersuits and drysuits in the covered dry changing area well in advance of slack water. They could then move aft outside onto Huskyan’s expansive dive deck and start prepping and getting into their rebreathers.

Team 2 would then get dressed in their drysuits in the changing area and would then assist the Team 1 divers, who were by now getting into their CCRs and clipping on bailout (stage) cylinders. Once slack water arrived and the Team 1 divers were beginning to jump into the water, Team 2 would be assisted by boat crew in getting into their own rebreathers and getting ready to splash. In this way, with the second wave of divers entering the water some 10 minutes after the first group, we managed to avoid 12 divers trampling all over each other and valuable kit. With bottom times down on the wreck of 35 minutes and run times inwater including trapeze decompression of about two hours, all the divers would be able to rendezvous on the trapeze for the final cast off and drifting deco hang.

Ben Wade and Greg Booth were to be the first to dive – their job was to make sure the shotline was on the seabed near the wreck and to secure it. They would be followed by Brian Burnett and Paul, who would take down the trapeze transfer line and connect it to the downline and add some spare cylinders of bailout gas. Then Gary Petrie and I would dive, our job being to add some more fixed bailout cylinders.

Dressed into my CCR and full rig, with my CCR safety pre-breathe done, I finally stood up heavily from the kitting-up bench and clumped gingerly to the dive gate in the gunwale. I could hardly believe that this moment had finally arrived.

Standing there waiting for the skipper to position the boat beside the downline, the familiar feeling of apprehension and excitement that I get before a big dive like this washed over me. I had been so consumed by the planning of the expedition over the last 18 months, securing the licence, writing to the Kirkwall police to advise of what we were doing, writing to advise the Coastguard and Orkney harbours of the licensed activity, the sheer logistics of getting everyone and all their kit to Orkney, the shakedown dives, the preparation …. And here, now, it was finally a reality – I was rigged in my CCR, bailout cylinders clipped under my arms, ready to jump. An unforgettable moment.

By the time I strode off the boat, Ben and Greg were already down on the wreck. The trapeze had been lowered into the water, and it self-deployed as Paul and Brian took the transfer line down and clipped it off to the downline. As I hit the water and the white froth of bubbles dissipated, I looked across to the downline which I could see dropping vertically down into the depths. The underwater visibility out here in the Atlantic was just as I remembered from my last expeditions 20 years earlier – astonishing for Scotland, at least 50 metres. I could see Paul and Brian below me; Ben and Greg were already out of sight below.

Gary and I moved over to the downline and started our descent. The water was absolutely slack; with no current at all, we could just freefall beside the downline.

As I reached 30 metres, where the transfer line from the trapeze had already been safely clipped in by Paul and Brian, Gary unclipped the spare cylinder of deep bailout he was porting and we clipped it off on the transfer line. It was set up so that when we recovered the trapeze and transfer line onto the boat after the dive, all the spare bailout gas would come out with it. Although the bow and stern downlines would be left for the duration of the exped, we wouldn’t be leaving cylinders on them. Deep bailout gas clipped off, it was time for Gary and me to continue our descent.

Although it was very dark beneath us, the underwater visibility was still crystal clear. Looking down the downline, as my eyes traced its path down and slightly up-current, I was astonished to see the dim silhouette of the wreck far below us. The dim pinpoints of the four divers’ torches, clustered in two pairs ahead of us, were visible at different points of the wreck. I could make out the upturned hull of the stern, and even see the long free section of the port prop shaft leading out from its tube to its circular bearing bracket, supported on struts connected to the main hull. This was the last memory I had from my dives on the wreck 20 years earlier – I’d never thought that I would be back here to see it again.

In the slack water, I was able to move away from the downline and make for the fantail of the wreck, which was lying upside down on the seabed. The seabed around the wreck was hard shale with scattered large Norwegian glacier melt boulders some several metres high. There is no silt and the wreck is clean, uncovered by sand.

Unlike the much larger capital ships of the day, Hampshire did not have a large elevated armoured superstructure, so when she capsized and hit the bottom, the lighter sections of her superstructure and her four smokestacks were crushed by her weight and momentum. The vessel came to rest almost completely upside down, but with a slight list to starboard, propped up by her 7.5-inch turrets and her conning tower.

The wreck of HMS Hampshire today lies in 68 metres of water.

Left: The ship’s name still rings around the fantail – now missing the HA. (Author’s collection)

The port 43-ton propeller of HMS Hampshire. © Ewan Rowell

I arrived at the stern at a depth of about 65 metres and Gary arrived soon beside me. With a quick exchange of OK hand signals, and a muffled ‘Are you OK?’ shouted through the mouthpiece of my rebreather in a squeaky helium Donald Duck voice, we turned to move forward along the port side of the wreck at seabed level on our first recce. I immediately started filming.

At the very stern, we could see how the two unarmoured upper deck levels had collapsed down and how the upside-down bulwark of the fantail was sitting a few feet aft of the more intact keel section of the stern. We could make out the large embossed letters of her name, MPSHIRE. The section of metal that would have held the HA was missing, having sprung somewhere as this section of the ship collapsed. The rudder lay fallen to the seabed nearby.

I moved forward, a few feet above a seabed that was littered with plating, spars and bits of ship. As I did so, the smooth intact steel of a large section of her keel began to rise up from the fantail and a gap began to appear between the seabed and this intact section of keel and hull. The keel swept upwards towards the vertical sternpost which would have held the rudder – and there just forward to port, and still supported on its bearing and struts, was the massive 43-ton manganese bronze, three-bladed prop – about 16 feet across according to the ship’s drawings. Sections of the underside of the quarter deck lay flat on the seabed to port, and it appeared that the ship had sagged to starboard as the higher levels collapsed aeons ago.

The gap between the seabed and the intact section of the ship continued to increase – and then the reason for this became apparent. The large gunhouse of the 7.5-inch gun Y turret, situated on the centreline of the quarter deck, was resting upside down on the hard shale seabed. Rising up from its underside, the cylindrical armoured trunking that held the ammunition hoists extended all the way up to the underside of the keel bar. The ammunition hoists transported shells and cordite propellant charges up from the magazines and shell rooms, far below the surface in the bowels of the ship, to the gunhouse. Inside the ship, adjacent to the hoist trunking, masses of 6-inch shells for her secondary armament and QF 3-pounder shells had tumbled down from above to litter the underside of her main deck, now at seabed level. High up on the wreck, the keel plating had split open to expose the port 7.5- inch shell room, the large shells still neatly stacked in rows.

The port side of the wreck aft has separated from the keel, allowing a glimpse of the 7.5- inch shell room. (Author’s collection)

In the astonishing visibility, I continued to fin forward at a depth of just over 60 metres. Just forward of the aftmost Y turret, the two-storey port 6-inch gun casemate came into view, its curved armoured side projecting from the hull. With the ship upside down, the 6.8-metre- long barrel of the uppermost casemate now lay flat on the seabed, pointing aft. The lower (now uppermost) of the two 6-inch casemate guns had been demounted from the casemate in 1916 and moved to the upper deck in place of one of the original 3-pounder guns. The resulting vacant gun port had been plated over to keep the sea out – and the plate was still very evident on the wreck, its centre now corroded through.

As I looked at the 6.8-metre-long barrel on the seabed, I noticed the end of the barrel of a 3-pounder sticking up through the sand at its end. Tracing back towards the hull, this led me to the base of its pedestal, which was sticking up from under the sand just under the bulwark. Forward of the casemate gun we would go on to find several more of these now upside-down 3-pounder guns.

The main (aft) mast ran out at right angles to the wreck along the seabed, with thick old- fashioned electric cables running from the wreck up inside it. Just forward from it, a sturdy steel boom for a steam pinnace or boom boat lay on the seabed. As the ship sank, the boom boats could not be swung out and lowered, as all power on the ship had been lost; the boom boats were still secured on her as she turned turtle and went down.

As I swam out along the mainmast, I spotted a small triangular Yarrow boiler from a pinnace lying on the seabed just beyond its end. As the ship turned upside down, this Yarrow boiler, which provided steam for the pinnace engine, had fallen from its mounts straight through the wooden roof of the pinnace to the seabed. There was no sign near it of the engine or any other parts of the pinnace –presumably still lashed to the wreck and its boom.

As I looked further forward from the mast and boom, I spotted a large object standing upright on the seabed about 15 metres away from the wreck. I remembered seeing this in 2000 when I dived the wreck last – but at that time, on open-circuit trimix and limited bottom time on the wreck, I had not ventured out to go and see what it was.

This time, not having the same gas constraints, I swam out from the wreck towards it. Once I got to about 10 metres away, I realised that it was one of the 6-inch guns (similar to the 6.8-metre long gun I had just seen in its 2-storey casemate) that had been demounted from the casemates and installed on the upper deck. As the ship turned turtle on the surface, like the Yarrow boiler, this gun, which weighed more than 8 tons (excluding the casemate protection) had fallen from its mount and plunged down through the water column like a dart. At least 4–5 metres of the 7-metre-long barrel had impaled itself into the seabed – I was looking at the last 1–2 metres of barrel and the breech block, all heavily encrusted in soft corals and dead man’s fingers. In the days to come we would find another 6-inch gun impaled upright in the seabed not far away, and a third that had failed to penetrate the seabed and was lying flat. The fourth 6-inch gun was found under the wreck itself.

Starboard aft shot of Hampshire showing the two-storey 6-inch gun casemate. The lower of these guns on both sides of the ship were demounted in 1916 and installed on the upper deck. (Author’s collection)

The two-storey casemate with the originally uppermost barrel lying on the seabed. The uppermost firing port has been plated over, the plate having now corroded in its centre. The main mast runs out on the seabed to right of shot. (Author’s collection)

To the east, one of the two 6-inch gun barrels which have impaled themselves some 5 metres into the seabed as they fell off the ship as she capsized. A third gun was found lying flat on the seabed whilst the fourth is under the wreck. (Author’s collection)

It was becoming clear as the dive went on, that lots of large items such as guns and boilers had fallen off the ship as she capsized – they were all lying in a debris field on the east or port side of the wreck as she now lay. This already confirmed wartime reports from the 12 survivors that she capsized to starboard on the surface.

I moved back towards the wreck and saw a row of portholes lying on the seabed along the side of the ship, in sections of hull plating. These portholes were originally situated in the unarmoured deck above the main waterline armour belt, and they had been still in situ in the ship’s side when I dived her last in 2000. Since then, the weight of the non-ferrous portholes had triumphed over the rotting, unarmoured shell plating, and one by one they had fallen to the seabed, taking large rotted sections of shell plating with them. The structure of the ship remained – minus the shell plating with its row of portholes, leaving a seemingly black horizontal expanse, which ran fore and aft for about 150 feet, opening directly into the innards of the ship.

Looking under the inverted main deck, which was in places a metre or two off the seabed, we began to make out several more of the upside-down QF 3-pounder guns that had been ranged along either side of the ship. As built, there were nine of these along either beam, but during refit in 1916 a number of these were demounted and landed to make way for the two lower 6-inch casemate guns that had been removed from either beam and installed on the upper deck.

I continued to move forward along the port beam. As I approached the area where the bridge superstructure would have been, now largely crushed under the ship, the crumpled port side of the bridge projected out to the east. The collapse of the bridge and the rotting away of shell plating had exposed a row of several upside-down toilets that gleamed white in our torches – the ship’s heads.

Above the crushed bridge superstructure, the armour belt plates were still pristine, although some had slipped from their mountings here and there, allowing a glimpse of their thickness. The end of the port 7.5-inch wing P turret barrel protruded from collapsed and fallen ship’s plating.

At this point, as I looked up the port side of the armour belt, the shell plating of the bottom of the ship, which had been largely intact all the way from the stern to this point, abruptly stopped at the bottom of the armour belt. I began to fin upwards, moving towards the original bottom of the armour belt.

As I reached the top (originally the bottom) of the armour belt, in the amazing 50-metre visibility, I was greeted by a panorama of the innards of the ship. The complete bottom of the hull from the armour belt on this side, to the armour belt on the other was missing – from about Frame No 38 all the way forward to the bow. Moving from aft forward, the largely intact keel plating of the bottom of the hull just stopped at Frame No 38 and was gone all the way up to the bow. It was as though the keel of the ship had been sliced across and the bottom of the ship completely removed all the way to the bow, visible far in the distance. All 37 hull frames – all the stringers that connected the frames, the double bottoms and shell plating – everything was gone.

The scene in front of me was just as it had been when I had visited the wreck in 1997 and 2000 during previous surveys, except that the leading edge of the intact section of hull at Frame No 38 had sagged downwards. This was just natural degradation of the ship and the effects of the passage of time. The damage to the hull here at the bow was not from the single mine that had sunk her in 1916. That would have blown in a few compartments, but certainly had not produced this level of damage. This was commercial salvage work – it looked as though the keel had been grabbed out.

Looking aft from near the bow reveals the extent of the damage to the wreck between bridge and bow before the hull reforms aft. The concave brass bulkhead of the lower control room can be seen, along with the starboard submerged torpedo tube. (Author’s collection)

On the starboard side where the keel reforms, keel plates have separated to reveal flashproof corrugated cordite propellant charge containers. (Author’s collection)

The keel plates where the hull reformed at Frame No 38 were coming apart at the joins as rivets turned to dust through differential corrosion, revealing ribbed boxes of cordite propellant underneath, inside the ship, on the port side.

As I hung in free water outside the ship beside the top of the armour belt plates and looked down into the exposed innards of the ship, initially a confused scene of jumbled devastation presented itself. The large cylindrical ammunition hoist trunking for the 7.5-inch gun of A turret, situated on the centreline of the fo’c’sle, lay on its side, its lowermost edge almost touching the far starboard side of the hull. To my left was a large transverse ribbed non-ferrous bulkhead – which was now concave from the effects of an explosion forward of it towards the bow. Across the ship on the far starboard side of the wreck I could see the long ribbed starboard beam 18-inch torpedo tube. In a later dive, I spotted the external torpedo hatch door lying on the seabed just off the wreck on the starboard side. There was, at this point, no apparent sign of the port 18-inch torpedo tube, which should have been almost right underneath me. Nearby, in the debris of the ship’s innards, lay torpedo bodies and warheads.

I continued forward along the top of the armour belt plates on the port side on this, my first initial orientation dive. A little way forward of the A turret ammunition hoist trunking, three large anchor capstan axles projected upwards from the debris. Royal Navy vessels were fitted with two bower anchors, one on either side of the bow, and a third sheet, or emergency, anchor on the starboard side abaft the bower anchor – so they had two anchors to starboard and one to port. In contrast, German World War I warships carried two anchors on the port side and one on the starboard side.

At the top of the three projecting capstan axle shafts (originally at their bases), each had a circular gear that would have been driven by a small steam capstan engine that was visible in the debris. The actual capstans themselves were originally situated on the fo’c’sle deck and were now hidden under the wreck.

The mouthpiece of the starboard submerged torpedo tube. (Author’s collection)

The three anchor capstan axle shafts are not distressed, bent or damaged in any way as from the effects of a nearby mine explosion. So it looked like the mine that sank the ship did not explode in their immediate vicinity. I spotted several dozen ribbed brass cordite propellant storage boxes in this area, which showed evidence of pressure damage to the cordite boxes themselves but no signs of explosive damage. Survivors had reported seeing a small explosion take place forward as she made her final plunge, and smoke and flame belching from just behind the bridge. There had been speculation that this had been a secondary ammunition explosion, but from the evidence before me it appeared highly unlikely that any secondary ammunition explosion had occurred in the bow magazines, as such an event would have consumed all propellant in the boxes in the area.

As Gary and I moved forward, we spotted the large port bower anchor lying on the seabed on the port side of the wreck. We swam over for a closer look and found that its stock was still secured in its hawse pipe in a detached section of unarmoured hull plating that would originally have been above the armour belt. Running along the plating were a number of fixed ladder rungs for crew. There was no sighting of the two starboard anchors, which may be buried under the wreck.

Looking back at the wreck, it was clear that the bow section of the ship was resting on the vertical armour belt plates. The two unarmoured fo’c’sle deck levels, lined with portholes and originally above the armour belt, were now crushed beneath the armour belt. This is in contrast to the section of ship from the bridge aft, where the deck level originally above the armour belt is still there, albeit minus the portholes themselves which have fallen to the seabed.

Gary and I arrived at the bow, which rose up magnificently for about 10 metres from a deep pit around it on the seabed. The base of the stem was completely intact – so at least we know she didn’t run bow first into the mine. The keel bar, one of the strongest parts of a ship, was still in place but bent smoothly over to starboard and angling down aft towards the seabed, where its severed tip rested on the shale about 20–30 metres aft of the stem.

By now, it was time for Gary and me to turn the dive and head back to the downline to ascend. To minimise decompression we finned up over the wreck until we were moving aft a few metres above the upturned flat bottom of the keel. We kept the video cameras running to record the less glamorous, but equally important, keel of the ship.

After a bottom time of about 35 minutes on this first dive, Gary and I arrived back at the stern downline. The other divers of the first wave were beginning to congregate around it, having kept to our agreed bottom times to keep us all loosely together. As we began to make our ascent up the downline we could see below us in the darkness, and further forward on the wreck, distant white pinpricks of the torches of the second wave of divers as they began to head back to the downline to begin their own ascents.

Gary and I rose up beside the downline and as we reached the transfer line at about 30 metres, we both removed our name tags before slowly beginning to cross over a seeming abyss towards the trapeze. Below us we could see the second wave of divers, now clustering around the base of the downline and beginning to silently rise up the shotline.

As the last divers reached the transfer line and removed the last name tags, satisfied that everyone was off the wreck, they disconnected the transfer line from the downline. The whole trapeze assembly now hung in free water, suspended from its own two large danbuoys on the surface. Slack water was long past, and the gentle current quickly began to drift us away from the fixed downline. As the downline disappeared from view up-current, we sent up a red DSMB on a reel to tell the skipper that all divers were up and decompressing on the trapeze – and that all was good.

We were disconnected and drifting, 12 divers clustered around the various bars of the trapeze, some hanging in free water just off it, to ease congestion. A long 90 minutes of uneventful decompression on the trapeze followed as we went through our decompression stops, culminating in long hangs at 9 metres and 6 metres.

As I finally finished my 6-metre decompression stop and began to move up one of the buoy lines that suspended the whole trapeze, I reflected on Day 1, Dive 1 of the exped, and what it had brought. We had already learned so much about the wreck on this first dive. What would the rest of the two-week expedition reveal?

Gary and I broke the surface after a run time for the dive of just over two hours, our heads spinning round until we spotted the attendant Huskyan. Once she turned towards us and started to close, now that it was clear that the crew had spotted us we let go of the trapeze buoy line. We rolled onto our backs and put our chests towards the gentle swell – this way we were facing into the waves and into the wind. We then kicked our fins gently and began to separate ourselves downwind from the trapeze buoys. We needed to be clear and downwind of the trapeze to give Huskyan plenty of room to come in close and pick us up with no risk of fouling the trapeze.

Once we had finned and drifted a good distance away from the trapeze, we stopped finning and just hung there in open water, two specks of humanity in the vastness of the Atlantic Ocean, waiting for Huskyan to make her pick-up approach.

After manoeuvring to get downwind of us, the Huskyan, with her lovely black and white bow, moved into the wind towards us. Very soon she was right beside us, the skipper, Russ, skilfully using her deadweight in the water to screen us from the seas and calm the water where we were. Russ then clicked the engines ahead to draw us down the starboard side of the vessel until we were just forward of the diver hoist. He then clicked the engines astern, to kill the water stream and stop with us dead in the water beside the lift gate. Huskyan’s spacious diver lift platform descended right beside us until it was deep enough in the water for us to swim onto it, one by one, and stand up.

Gary moved onto the lift platform first, as I held onto the grab line strung along the side of the vessel, waiting my turn. Once he was standing on the submerged platform, in water up to his chest, he marshalled all his cylinders, reels, torches and kit to avoid a snag before giving a nod of his head to crewman Ross Dowrie. The diver lift rose up from the water until the platform was at deck level, where Ross helped Gary and his 85kg of kit over the deck, and got him carefully seated on the kitting-up bench.

With Gary safely aboard, the process was repeated for me, and I was also soon on deck, being assisted to sit down in my heavy kit by Ross, who quickly whipped off my bailout cylinders, closed the valves and stowed them upright in the cylinder racks.

Once I was safely seated on the bench, I remained fully rigged and breathing from my rebreather, relaxing and breathing almost pure O2 through the rebreather for 3–4 minutes. I had learned the hard way after a bad exercise-induced bend in the North Channel off Ireland, that it’s best to sit still and simply do nothing after a deep technical dive.

Safety period over, once I was comfortable and relaxed I pulled the gag strap over my head, dropped the CCR mouthpiece from my mouth, pulled my 10mm neoprene dive hood back and pulled my mask off. A steaming pint of tea was immediately stuck in my hand by Ross – it’s something of a tradition on the Huskyan, and is much appreciated after a cold two- hour dive in 8°C water. As Gary did the same, we exploded into animated chatter about what we had just seen, the words tumbling out of our mouths like someone rapidly beating a drum.

‘Did you see the pit around the bow? That’s not a scour pit: she was 144 metres long and sunk by her bow in 70 metres,’ I said. ‘Looks like her bow hit the seabed whilst her stern was proud of the water – and then as she capsized to starboard her bow ground this pit in the seabed.’

‘The keel bar is severed 20–30 metres away from the stem. It’s the strongest part of the ship – so that might be where the mine hit?’

‘Right, so if the keel bar was severed and she then ground on the seabed as she capsized to starboard, maybe that’s why the keel bar is smoothly bent over to starboard and off the starboard side of the wreck.’

‘Did you see the concave brass transverse bulkhead just forward of the conning tower? That’s bent from a blast forward of it.’

‘Did you see the 6-inch guns impaled upright into the seabed? There’s all sorts of things in a large debris field that have fallen off the ship as she capsized out to the east – there’s nothing on the seabed to the west.’

And so, the chatter went on as we sipped our tea – still in our full rigs. But very soon our initial thoughts and impressions had to stop, as other divers started to pop up to the surface after completing their own deco. We quickly wriggled out of our rebreather harnesses and were soon at the lift, as the Huskyan came in to pick up the next group of divers, who were now well away from the trapeze. Over at the trapeze, other divers were now beginning to surface, slowly starting to fin away and wait for their turn to be picked up.

As other divers came up the diver lift and heavily clomped down on the dive deck benches, the level of buzz and excitement escalated. Everyone was amazed at what they had just seen – each had spotted something unique. Whilst it was a simple joy to see such experienced divers clearly blown away by the experience, immediately I could see just how gifted a group of individuals they were.

Once we had all de-kitted and changed out of our drysuits into our dry clothes, we all gathered in the Huskyan’s spacious saloon, where even more pints of tea were served along with skipper Emily Turton’s justly famous home bakes. You do get treated extremely well on the Huskyan!

In addition to Huskyan’s famous hospitality, Emily is also legendary for her fantastically detailed dive briefings and whiteboard drawings on her regular Scapa Flow dive trips. In advance of this expedition, she had had a huge whiteboard wall mounted in the saloon and as we all sipped tea and ate cake, she sketched out on it the upturned hull of the Hampshire on the seabed.

We had agreed to hold a debrief every day on the passage back south to Scapa Flow to capture everyone’s memories in a formal way, before the days began to merge into one another and memories became muddled and lost. Once the basic outline was up on the board, we went around each of the divers one by one, asking them to take their turn at the whiteboard, saying what they saw and where. Emily then added the things they had seen, like the impaled 6-inch guns and the pinnace Yarrow boilers, in the right locations on the whiteboard. The process took about an hour, and it was clear that even after Day 1 we already had a good idea of the layout of the wreck.

The following day, it was reveille at 0600 for Dive 2. We were all aboard the Huskyan and ropes were being cast off by 0715. We headed south into Scapa Flow from Stromness before turning to the west to pass out through Hoy Sound. Once through the tidal and often very difficult waters of this sound, the Huskyan turned her head to the north for the run up the coast to the wreck site. The weather was beautiful again – the sky was a crisp clear blue, the sea calm, with a long rolling swell coming in from the Atlantic.

Whereas yesterday the task had been to establish a fixed downline near the stern of the wreck and explore it from there, today we would deploy a second shotline on the seabed near the bow and start our exploration from this area. The trapeze could then be deployed on either fixed shot as required each day – divers would know exactly where they would arrive at on the wreck and it would assist becoming familiar with the wreck.

As with the day before, we arrived on site a couple of hours before slack water. The buoys from the fixed shotline deployed at the stern the day before were still floating in position, marking where the wreck lay. Arriving well in advance of slack water like this gave ample time for Ben and Emily to get the boat positioned just off the bow and drop a second weighted shotline to the seabed. This was a fully munitioned warship as well as being a sensitive war grave, and we did not want to damage it in any way with a careless shot deployment. As with the placing of the shot on the seabed near the stern yesterday, Ben and Emily spent a considerable amount of time getting a feel for the exact positioning of the wreck far below before the signal was given to drop the shot.

As the shot weight went over the side, the coiled rope paid out quickly from the deck, only arresting its frantic deployment as the shot landed on the seabed. The rope had been precut to the length required and already had a couple of fisherman’s floats attached to its end; they had insufficient buoyancy to drag the shot away from the wreck. The tide would drag them under until it went slack, when they would pop up to the surface again and make it clear it was time to dive. The first divers in would attach a large danbuoy to the shotline as they went in, to give buoyancy in case there was some sort of emergency during the dive itself. We all clustered in the saloon for our dive briefing and allocating of tasks and areas of operation for each pair of divers. Dive briefing over, it was time to start getting kitted up.

As with yesterday, Ben and Greg Booth would dive first to fix the shot near the wreck. Paul Haynes and Brian Burnett were next into the water, as Ross got the self-deploying trapeze into the water, taking spare gas and the transfer line down the shotline to clip it on at 30 metres. Next, Gary and I would splash.

As I righted myself after jumping off the boat into the water, I finned over to the downline. The trapeze was already hanging fully deployed in free water nearby – I could follow the transfer line from it all the way down into the depths to where Paul and Brian had already clipped it to the downline far below.

Gary and I had a round of OK hand signals and then started our descent into the beautiful crystal-clear water that surrounded us. We were hanging seemingly in the open expanse of the Atlantic – below me it was dark, and as yet there was no sign of the wreck far below.

The tide was now totally slack and so Gary and I let go of the downline and began to freefall deeper into the darkness. Gradually the darkness below took on a familiar form, unnatural straight lines began to coalesce to a point – the unmistakable upturned bow of HMS Hampshire. Far below in the darkness, I could see the shot sitting on the seabed just forward of the port side of the bow. There was no need for us to go over there, so we left the downline and headed over to the ship.

The ripped-open forward section of the keel at the bow, from bridge to stem, was right beside and below us. In the lovely visibility, I could see the full beam of the ship and how the two sides of tapered armour belt swept together towards the stem. The vertical armour belt plates protecting the most important parts of the ship, such as the engines, boilers and magazines amidships, were 6 inches thick, but these tapered towards stern and bow, outwith the citadel. The vertical armour plates beneath me here at the bow appeared to be about 2 inches thick. Inside the exposed innards of the ship I could see the now familiar cylindrical ammunition hoist trunking for A turret, the starboard beam torpedo tube abaft it – and the three capstan axles and circular gears nearby, ahead of it.

As I hung in free water above the wreck I studied this open area in more detail. There was still no trace of any of the keel frames, stringers or shell plating of the hull. Everything above the vertical armour belt plates of either side was gone. In the confused debris of ship’s innards here I spotted a number of torpedo bodies, a number of separate torpedo warheads, shells for the 7.5-inch main guns and for the 6-inch casemate guns, and masses of corrugated rectangular brass tins holding cordite propellant charges for the guns. Cordite propellant was stored separately from shells in magazines well below the waterline of warships.

We spent the dive as planned around the bow, filming the debris area of the missing keel. I swam over to the starboard side of the wreck and spotted the beam torpedo tube mouthpiece lying on the seabed. Nearby a complete torpedo body lay parallel and up against the side of the ship, partly obscured by a fallen piece of plating. Why was this torpedo outside the ship on the seabed, unlike the others which were inside?

Whilst it was clear there was a rich debris field on the east side of the wreck facing towards Orkney, as I looked out over the seabed to the west, towards America, there appeared to be nothing at all lying on the seabed. To make sure I kicked my fins and ventured about 50 metres out over the seabed to the west, keeping the wreck in sight behind me in the glorious visibility. The seabed was clean shale with no debris at all to the west.

After another 35 minutes on the bottom, it was time for us to begin our ascent. After we and the other divers were all safely back aboard after long decompression hangs, Emily and Marjo Tynkkynen reported a stellar piece of work – they had spotted, just off the bow in the pit, a small circular artefact, about 8 inches across, that was green with verdigris and clearly non-ferrous. They had carefully photographed it with a ruler placed alongside it for scale. During our post-dive debrief, Emily and Marjo put the images of it up on the Huskyan’s saloon screens. The central part of the object had an embossed rose that was surrounded by a garland of leaves that ran right around the outside of the object. There were four screw holes in its face. At first, we were all a bit non-plussed as to what it was, but the more we looked at it, the more it became clear that what we were looking at was a brass face plate for a tampion for one of the forward 7.5-inch main battery guns. These tampions were essentially leather-covered wooden plugs that were inserted into the end of the gun barrel when not in use to keep out sea water and the elements. They usually had a colourful decorative outer plate screwed to the tampion itself, carrying a motif personal to the ship. In this case, the rose surrounded by a crown or garland of leaves was the emblem of the county of Hampshire, after which the ship was named.

The tampion plate was lying off the ship – and not directly beside either the forward A turret 7.5-inch gun, which was under the upturned fo’c’sle deck, or the port P turret 7.5-inch gun, whose open barrel protruded from debris at the side of the ship some way away, near the bridge. We talked it through and surmised that as the ship turned turtle on the surface and then sank, increasing water pressure had perhaps compressed the air in the gun barrel, driving the wooden plug up the barrel a short way and forcing the tampion plate to pop off and fall to the seabed.

During the debrief we were able to add many more features to our whiteboard recreation of the wreck – it was already starting to become a busy whiteboard.

The next day, we gathered in the saloon of Huskyan as we ran up the coast once again to the wreck site. Now that we had covered and filmed the whole wreck in overview, now that there were fixed downlines at the bow and stern, it was time to start looking at particular features in detail.

Local diving historian Kevin Heath of Sula Diving in Orkney had carried out detailed side- scan sonar mapping of the wreck site in advance of our arrival. His preliminary work proved particularly useful in identifying large objects lying off the wreck in what had transpired to be the debris field of items that had dropped from the ship as she turned turtle on the surface. Each day, pairs of divers were assigned a particular task – and using Kevin’s scans we could now take bearings from fixed points on the wreck to these objects out in the debris field, and send divers out to check them out.

Some of the divers were using diver propulsion vehicles (DPVs) and were able to cover large areas of the seabed quickly. There were some very big lumps on the seabed more than 200 metres off the wreck, and Paul Haynes and Brian Burnett were sent out on scooters to investigate those. These turned out to be large Norwegian glacial melt boulders, the size of an SUV.

Paul Toomer and Mic Watson were a very strong buddy pair who worked well together – they were tasked to go and devote a dive to filming in detail the upright 6-inch gun, impaled in the seabed, that was the furthest gun off the wreck. As they were doing this they noticed a dinner fork lying on the seabed beside the gun. Their videography was so good that when Kari Hyttinen worked on the 3D photogrammetry data processing that evening, as the gun materialised out of the point cloud data during processing, the fork could clearly be seen gleaming on the seabed beside it.

Gary and I were tasked on one dive to film the entire starboard side of the wreck – the ‘low side’. The ship was canted over, propped up on her turrets such that her port side was slightly higher. Even although the hull on the low side was sunk well into the seabed, this dive turned out to be particularly interesting.

In 1983, the wreck was dived by a commercial consortium, who obtained a licence to survey and film it from the UK MOD, using the Aberdeen oil field diving support vessel, the Stena Workhorse. The 43-ton starboard propeller was stated to have been found lying on the seabed beside the wreck. The licence precluded removing items from the wreck – but the consortium believed it did not prevent them from recovering items lying on the seabed around it. The prop and shaft was lifted and the recovery reported to the Receiver of Wreck in Aberdeen. The prop and shaft were offloaded onto the pier at Peterhead when the vessel arrived there on completion of the works, and lay there for more than a year until it was sent to Orkney where it is now on display at the Scapa Flow Visitor Centre and Museum at Lyness on the island of Hoy. We were able to locate the shaft tube, where the prop shaft had broken off – or been cut off – just as it emerged from the shaft tunnel.

Kari Hyttinen and Immi Wallin spent their days filming the wreck slowly and meticulously in hi-res for photogrammetry with Prof Chris Rowland, the Director of the 3DVisLab at Dundee University, acting as supporting light. Chris is at the leading edge of underwater imaging with the company ADUS Deep Ocean, which was brought in to image the Deep Water Horizon in the Gulf of Mexico, and the Costa Concordia. Chris would assist with the photogrammetry and go on to do the virtual reality 1:1 aspect ratio, actual-size modelling of the wreck. Emily supported Marjo Tynkkynen in taking hundreds of hi-res still images and fully cataloguing the wreck. As the days went past, so our knowledge of the wreck increased – and so Emily’s whiteboard became more and more full.

Week 2 of the expedition was soon upon us – and whereas the first week had been blessed with benign seas and awesome underwater visibility of up to 50 metres, during the second week the seas blew up and a plankton bloom closed the vis on the wreck down to a black 5 metres. This was frustrating but not a significant problem, as we had already filmed the wreck in detail and knew the wreck so well by then that we could still easily navigate our way around it to spend our time finding and mapping the smaller details.

The Daring-class Type 45 destroyer HMS Duncan was scheduled to be moored in Kirkwall for the 100th anniversary commemoration event above the site and the simultaneous ceremony at the Kitchener Memorial on Marwick Head. She is the sixth and final Type 45 destroyer to have joined the Royal Navy in 2010. She is 152 metres in length, just a little longer than the 144-metre long Hampshire. Despite being slightly longer, the unarmoured Duncan displaces 8,000 tons as opposed to the 10,800 tons displacement of Hampshire.

As the conditions of our licence prohibited us diving on the actual 100th anniversary of the sinking, 5 June 2016, the whole team was kindly invited for a tour of Duncan the night before. The four expedition co-organisers were also invited back for lunch aboard on the 100th anniversary itself by her commander, who warmly welcomed us and was very supportive of what we were trying to do. After a very pleasant lunch in his private rooms, we were able to show him some of our underwater footage and stills photographs, and explain how our buoys were laid out on the site; he would be going out to the site that evening for the ceremony.

That evening, 5 June 2016, the 100th anniversary commemoration event took place at the Kitchener Memorial atop Marwick Head at 2045, the exact time that the Hampshire hit the fateful mine. Our whole dive team attended the ceremony – and it was particularly moving for us to see offshore in the distance, silhouetted against the late summer’s setting sun, HMS Duncan sitting above the wreck of the Hampshire. It was a powerful and moving image – and it was slightly strange to be in amongst so many interested people and officials to think that we would be diving down to the wreck the following day. Representatives of the Metropolitan Police from London were present as their man, Matthew McLoughlin, was Kitchener’s personal body guard and was lost as the ship sunk. The Met would subsequently approach me to indicate that a suite of offices in their Royalty and Specialist Protection Command centre was going to be named after the late officer, who was the last Met officer to lose his life on protection duties. They asked for some imagery of the wreck to display in the new Matthew McLoughlin Suite. We were of course happy to oblige for such a worthy cause, and forwarded a number of stills. The suite was subsequently opened by the Princess Royal on 19 October 2016.

In the days following the 100th anniversary ceremony at Marwick Head, the commander of HMS Duncan sent me a note to say that the buoys had been very helpful in positioning his vessel at the correct site and in the correct orientation for the ceremony.

From our examination of the wreck, it became clear that with a length of 144 metres, as the Hampshire sank by the bow, her bow struck the seabed as her stern lifted out of the water 65 metres above. She then rolled to starboard and capsized on the surface. Everything that wasn’t secured to her fell from the upside-down ship to create a debris field on the seabed to the east. Her four deck-mounted 6-inch secondary armament guns fell from their mounts and dropped through the water column, two impaling themselves like darts into the seabed.

Her two towering masts struck the seabed on the eastern side of the wreck and broke in several places. The small Yarrow boilers for her steam pinnaces fell through the pinnace roofs and landed to the east; the pinnaces themselves, still secured to the booms were pinned to the side of the wreck.

A drifting decompression on the trapeze on the final day was a chance to fly the Explorers Club flag inwater. Rod Macdonald on the left – Paul Haynes, right.

Over more than 100 years since her sinking, the wreck has sagged and collapsed in places, but she is very much recognisable for the fine ship she was. An armoured ship, strongly built, she has stood up well against time, tide and the fierce Atlantic storms.

As at the date of printing we have our 120-page-long Explorers Club Expedition Report almost finalised. It will be kept by the Explorers Club along with all the other reports of expeditions going right back to its genesis in the early 20th century. The report will also be circulated to other interested bodies such as local museums and national institutions such as the Imperial War Museum and the National Maritime Museum. The 3D photogrammetry and virtual reality modelling is well under way, but will take some time to finalise. I subsequently went down to the University of Dundee to visit Chris Rowland in the 3DVis Lab. Putting on the VR goggles, you are immediately transported to the wreck of the Hampshire, which at full size appears to tower 50 feet above you. The level of detail is incredible, and once the VR model is finalised I will be interested to hear what maritime archaeologists will say about being able to walk around the wreck of the Hampshire.

The wreck is designated as a Controlled Site under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986 (Designation of Vessels and Controlled Sites) Order 2012 and no diving has been permitted on it or within 300 metres of it since 2002. With our survey under licence now completed, it is unlikely that another licence will be granted to survey the ship in the foreseeable future. I wonder what she will look like on the 200th anniversary of her sinking and how our 2016 results may be pored over then?