Читать книгу Spy Sub - Roger C. Dunham - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

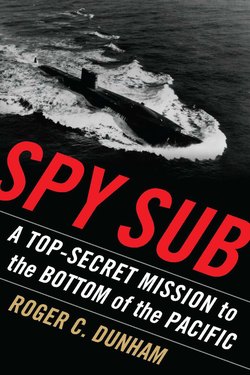

REPORTING ON BOARD

IN MOSCOW ON THE COLD morning of 29 March 1966, the Twenty-Third Congress of the Soviet Communist Party convened at the Kremlin for the first time since the death of Nikita S. Khrushchev. In his inaugural speech before the five thousand delegates of the Communist Party’s supreme ratifying body, First Secretary Leonid I. Brezhnev called for world Communist unity as he acknowledged the rapidly deteriorating relations with the United States. He protested the “bloody war by the United States against the people of South Vietnam” and called upon the Soviet military forces to continue their achievements in science and technology.

The delegates reviewed the Soviet report on military power that underscored the increasing size of their armed forces, including the Red Navy’s impressive submarine fleet. They affirmed the strategy of maintaining 400 nuclear and conventional submarines in four major flotillas around the world, and they agreed to continue building their submarine fleet by 10 percent each year. The Pacific Fleet, second in size only to the massive Northern Fleet, contained 105 Soviet submarines. Many of these were of the lethal nuclear missile-carrying “E” (Echo) class that regularly patrolled the ocean waters east of Kamchatka Peninsula.

In contrast to this massive Soviet armada of submarine military power, the United States Navy possessed only 70 nuclear submarines; 41 of these vessels were designed to fire nuclear missiles and most of the others were fast-attack hunter/killer submarines. One of them, however, differed from all other submarines throughout the world.

In the spring of 1966 at the Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard near Honolulu, Hawaii, civilian shipyard workers finished a year of intense refitting on board the nuclear submarine USS Viperfish (SSN 655). As the Twenty-Third Congress of the Soviet Communist Party adjourned its meeting on 8 April 1966, the U.S. Navy completed the process of gathering together a volunteer crew of 120 men to serve on board the Viperfish. This crew of submariners, civilian scientists, and nuclear systems operators began one of the most remarkable top secret military operations in the history of the United States.

The code name of this special mission was Operation Hammerclaw.

THERE WAS NO WAY for me to know that the nuclear submarine Viperfish was a spy ship when I received my orders to report for sea duty.

The terse sentences on the order sheet arrived on a miserable day, a New London kind of day. Freezing winter winds blasted across the Connecticut submarine base, and the driving rain brought torture to anyone who dared to go outside. The drab buildings of the civilian city across the gray Thames River looked like dirty blocks of clay stacked along the water’s edge. They seemed to fit perfectly with the dismal weather and the depressing area that must have been filled with people wanting to escape somewhere-anywhere. As a native Southern Californian who had just completed three years of submarine and nuclear reactor training, I not only craved a warmer world but I was also eager to begin the real work of running a reactor on a submarine at sea.

I had turned in my “dream sheet” weeks before. Created to give direction to the complex process of assigning personnel to duty stations, the dream sheet at least gives the illusion that the Navy tries to match each sailor’s desired location with the available slots throughout the world. I had “wished” for the USS Kamehameha, a Polaris submarine based in Guam and skippered by someone I had known before joining the Navy. The island of Guam appealed to me because of its warm water and proximity to Hawaii, in addition to the fact that it was as far away as I could get from the submarine base at New London.

I paced back and forth within the protective interior of the musty barracks and studied the printed sheet of orders before me. The words were tiny, and I found it remarkable that such small words contained information that defined my future for the next three years: “You will report to the commanding officer of the USS Viperfish SSN 655 at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.”

“The Viperfish?” I asked into the empty barracks. “What kind of a ship is the Viperfish?”

Studying the orders, I searched for any kind of clue to define the vessel. She was a fast-attack nuclear submarine; the SSN (submersible ship, nuclear) before her hull number 655 left no doubt about that. Clearly, however, the Polaris option was out. The Viperfish was in Hawaii, the land of beautiful women and the aloha spirit, the land of warmth and excellent surf, the land that-compared with New London-was close to heaven. I scanned the order sheet again for clues about the future mission of the submarine.

To my delight, my bespectacled machinist mate friend in submarine school, Jim McGinn, was also assigned to the Viperfish. Looking more like a scientist than a sailor with his wispy red hair and round glasses, Jim projected a deservedly scholarly image. He excitedly popped through the barracks door that afternoon, as he waved his orders, and asked me if I knew anything about this thing called the Viperfish.

“I heard we’re the only guys from our class to get this boat* It must be some kind of a fast-attack,” I said, offering my best educated guess. We had just completed hundreds of lectures in submarine school, and we knew there were two primary types of nuclear submarines. The majority were the SSNs, the sleek, high-performance fast-attack submarines that engaged in war games of seeking and tracking enemy submarines on the high seas. The others were the “boomers,” big, slow submarines, such as the Kamehameha, that functioned as submergible strategic ballistic missile launching platforms. Because the Viperfish did not carry the SSBN designation of a boomer, she had to be one of the Navy’s hot fast-attack submarines.

“But why doesn’t anybody know anything about the boat?” Jim asked. “They know about all the other fast-attacks. I’ve asked everybody.… The Viperfish is like some kind of a mystery submarine.”

“Probably because she’s one of the newer ones,” I said, “and her home port is at Pearl Harbor, on the other side of the world.”

Jim smiled and looked at the cold world outside the barracks window. “Thank God for that, in warm and beautiful Hawaii.”

Cursing the bone-chilling wind and rain, we crossed the base to the military library and pulled out the most recent edition of Jane’s Fighting Ships and searched for the Viperfish. We first discovered that she used to be designated a guided Regulus missile-firing submarine. The range of the Regulus I missiles was five hundred miles, far below the thousand-plus range of the more modern Polaris missiles, although this range would be improved by the larger Regulus II missiles to one thousand miles. Each Regulus missile had stubby wings on either side of a fuselage carrying a jet engine that powered it to the target. When properly prepared in a time of war, its 3,000-pound nuclear warhead would then detonate at the appropriate time.

Jim continued to study Jane’s information and search for more clues about our submarine. “What class is the Viperfish?” he asked, referring to the general class that often identifies the mission of a naval vessel. When we found she was in the Viperfish class, we began to feel depressed.

We both looked at the picture of the submarine and scanned the story. The Viperfish was definitely not a sleek vessel by any standard. She was commissioned in 1960 at Mare Island Naval Shipyard, with strange bulges and an unusual stretched-out segment in the front half of the hull, presumably to provide a stable launching platform for the five guided missiles previously stored in a hangar compartment within her bow. She was clearly not designed for speed, with a maximum submerged velocity of only twenty-five knots (compared with the forty-plus knots of most fast-attack submarines). Her superstructure was flanked with long rows of ugly-looking holes (limber holes or flood ports) along both sides, designed to allow seawater to enter the external shell of her superstructure during submerging operations.

McGinn continued to read the description. “The Viperfish was originally intended to be a diesel submarine,” he said, “but at the last minute, they changed their mind.”

“So they thought it might run better on nukie power,” I said, “not having to run to the surface to pull in air for charging the batteries or running the diesel engine. Since I am a reactor operator, it is good that she has a nuclear reactor. Now what does she do?”

We hunched over the book. “Nothing else here,” Jim said. “Whatever she does, the Viperfish is a regular SSN, sort of. When they took off the missiles, they got rid of the G designation previously signifying that she carried guided missiles.”

I looked back at my orders. A tiny box at the corner of the sheet was labeled: “Purpose of Transfer.” Within the box were the cryptic words, “For duty (sea).”

What we did not know at the time was that the Viperfish had been further redesignated as an oceanographic research vessel during the SALT (Strategic Arms Limitations Treaty) talks. The fact that she carried a substantial firepower of live torpedoes did not change the benign research vessel designation; therefore, she escaped being counted as a nuclear fast-attack warship for the purposes of the treaty. At that moment, however, she appeared to be some kind of a weird fast-attack submarine that carried no missiles.

I was becoming confused. “So she’s a slow-attack submersible ship, nuclear-”

“Called the Viperfish… even the name is strange for an attack submarine. What the hell is a viperfish?”

We looked up the creature in the dictionary and found nothing. An encyclopedia also did not consider the animal worth mentioning, so we finally turned to a dusty fish book with faded color photographs of sea life.

“Here it is!” Jim said, pointing at a picture of a thick black fish with a huge mouth. “It’s a deep-ocean fish with a hinged jaw and photophores that create a beacon of light…”

“It eats dead fish, grabbing them whole as they sink to the depths below,” I added, studying the picture showing a single blue eye located above a glowing red streak.

“Viperfish. Couldn’t they come up with a better name?”

“Ugly fish, ugly submarine, eats dead debris.”

“With a huge glowing mouth. What are we getting ourselves into?”

No matter how we tried to embellish the Viperfish, it did not look like a submarine that would ever do anything impressive. She was slow and ugly, and she had a strange name. We trudged back to our barracks and listened in silence to the other men talking excitedly about their assignments on board such vessels as the Dragonfish, Nautilus, and Scorpion.

A couple of days later, McGinn and I left New London to spend time with our families before the final trip to Hawaii. When my friends in California asked about my submarine assignment, I could not avoid telling them. “Although the details are currently top secret,” I said, with the secretive air of someone having insider classified information, “the Viperfish is one of those SSN fast-attack nuclear submarines equipped with state-of-the-art firing power. Furthermore, it is jammed with unique experimental military firepower, the only one of her class in the world.

“No further information can be revealed at this time,” I added in the hushed voice of somebody describing a CIA operation and left the rest to each person’s imagination. In other words: “Don’t ask any more questions, because nothing more can be revealed-it is all secret.”

The conversations always ended with just the right amount of admiration and respect. For a twenty-one-year-old man ready to travel around the world in a submarine that was already an enigma, I could not have asked for more.

I flew to Hawaii on a civilian airliner contracted to the military at Travis Air Force Base in Northern California. The aircraft was packed with soldiers en route to Vietnam, and the atmosphere was filled with their gloom. The conflict in Southeast Asia was undergoing a rapid escalation at that time, and the depressed mood of the soldiers left little doubt about the fate they perceived at the end of their flight. The burly master sergeant sitting next to me looked miserable and said almost nothing throughout the entire trip.

When the plane landed at Honolulu, the sergeant just stared out the window at the clusters of vacationing tourists disembarking from nearby aircraft. As the plane doors opened, the sound of Hawaiian music entered the cabin, the fragrance of Plumeria blossoms floated through the air, and the lucky few of us assigned to Hawaii could not get off the plane fast enough. Jim arrived in Hawaii on a different day, but his flight carried a similar sad group of men. The memory of the unfortunate soldiers on that flight stayed with me during the tough times of the Viperfish’s submerged operations and somehow made my work seem easier by comparison.

I called Pearl Harbor from the airport and was quickly connected to the Viperfish.

“USS Viperfish, Petty Officer Kanen speaking,” the young voice fired out. “May I help you, sir?”

Thirty minutes later, a chief petty officer from the Viperfish jumped out of a car, asked my name, and firmly pumped my hand.

“Welcome to Hawaii, Dunham, I’m Paul Mathews, from the Viperfish-you’re one of the new nukes, aren’t you?” He was in his middle thirties, I guessed, a strong-looking man of average height and weight, and full of enthusiasm when I told him that I was a reactor operator ready to report on board.

“Throw your seabag in the back of the car,” he said with a smile, “and we’re on our way to Pearl. I’ll give you a ride even though you are a goddamn nuke.”

As we drove down Kamehameha Highway under the blue sky and brilliant tropical sunlight, Chief Mathews told me more about the Viperfish. He confirmed that the submarine had been designed to launch Regulus missiles, each equipped with a large nuclear warhead and fired from a rail launching system on the topside deck of the Viperfish. He told me that, during the past few years, the Viperfish had made several deployments to the western Pacific Ocean with nuclear missiles stored inside the cavernous hangar compartment in the front half of the submarine. During this time, she was the front line nuclear deterrent force for the United States.

The Viperfish had made a total of thirty-two test firings of Regulus missiles at sea. Each shot required the crew to surface, open a large door (christened the “bat cave” by the crew), roll a Regulus missile out of the hangar and onto its track, establish radio contact with the guiding system of a nearby American jet, and then finally fire the thing into the sky. The entire operation took about twenty minutes. Immediately afterward, the crew rapidly closed the bat cave and rigged the boat to dive so that, as quickly as possible, the Viperfish could disappear beneath the surface. The Regulus system provided nuclear protection prior to development of the Polaris missile program and construction of the first Polaris submarine, the USS George Washington (SSBN 598).

“With the Polaris missile system now going ahead full steam, the Viperfish isn’t involved with Regulus missiles, right?” I asked Chief Mathews the obvious as we entered Pearl Harbor’s main gate.

“Right,” he answered. “They unloaded the missiles and changed her back to SSN.” There was a period of silence, and I waited for him to continue.

Finally, feeling stupid, I blurted out, “Okay, what does the Viperfish do now, Chief?”

He hesitated, then began speaking in slow, measured tones. “Although her mission is secret, she has been redesigned to perform activities that you will find extraordinary. Because of these changes, there are now three crews on board the boat. There is the nuclear crew, composed of goddamn nukes like yourself, and the others who keep the reactor on the line and the steam in the engine room.”

After turning left past the main gate, we were moving in the opposite direction from the arrows pointing to the submarine base.

“And then there is the forward crew, the men who really run the boat,” he said. “They are occasionally called the forward pukes by the nukes-our shipmates to the rear. The non-nukes run the ballast control systems, the diving station, navigation, sonar, fire control-”

“I understand all that, Chief,” I interrupted. “And the third crew?”

He took a deep breath, stared straight ahead, and softly said, “The third crew is for the Special Project.”

We turned right, drove down Avenue D and into the naval shipyard. “What kind of special project, Chief?” I asked, sensing that I was going to learn little.

“You’ll find out all about that from your security briefing, Dunham. All you need to know for now is that we are developing a combined civilian and military project, a cooperative effort, so to speak, that expands the capabilities of the Viperfish.”

Although the prospect of civilians being assigned to a nuclear warship seemed unusual and even a little unsettling, it was apparent that the chief was not going to say anything more on the subject. We made a right turn off South Avenue to 7th Street, where a cluster of towering shipyard cranes came into sight. Mathews began talking about cranes as we approached the dry dock area. He said that the largest cranes were of the “hammer-head” style, as unique to Pearl Harbor as the Arizona Memorial.

The Viperfish was not moored at the Southeast Loch submarine base with the other submarines. The Viperfish wasn’t even in the water. Mathews parked the car, and we walked in the direction of the biggest dry dock, looming like a gigantic rectangular hole ahead of us. I stopped at the edge of the massive concrete chamber and stared down at the submarine that was to be my new home for the next three years.

* The term “boat” is generally used to denote a small vessel that can be hoisted on board a ship. Early submarines were small enough to fulfill this definition. The camaraderie of the first “boat sailors” and their pride in serving on board such unique vessels resulted in this term remaining in common use among submariners. The official U.S. Navy definition of a submarine is a ship, but submarine sailors, in accordance with tradition, continue to call their vessel a boat.