Читать книгу No Turning Back - Roger Rees - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1: Travelling

Map of Ethiopia

Addis Ababa, 1985

IT WAS A TIME of tumult. The second great Ethiopian famine of the twentieth century was ending. Detritus of human and animal corpses were everywhere, and in the countryside death’s pallor was on every face.

Slowly, very slowly, food distribution was beginning to reach isolated villages, but only after a million people had died. Unrest and anger, accompanied by a sense of hopelessness, was felt in every village and small town.

Spend a few weeks with me and you will learn what famine does to people and how we can make sure this never happens again, wrote the Ethiopian anthropologist Zeno Wolde to his visiting students, among whom were the young Australian anthropologist Louise Davitt and her British colleague Carmen Smith. They had just flown into Addis Ababa from Heathrow Airport to begin a month’s fieldwork with Zeno.

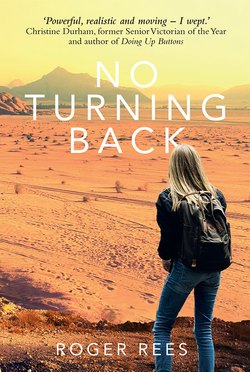

Louise, originally from country South Australia, was twenty-three: confident, blonde, tall, slim and adventurous. Carmen, a twenty-four-year-old Lancastrian, was short, dark-haired and rather plump. As an independent, working-class girl, she was well read and had a passion for fun and travel. They were both writers … Louise was a poet and brilliantly observant; Carmen was a chronicler of travel and history with, like Louise, impeccable research talents. They had met nine months before at London University, where both were enrolled in a postgraduate doctoral program. Within a week of introducing themselves they were friends.

They were picked up at the airport by Abebe, Zeno’s Addis University driver, in an old diesel Nissan Patrol 4WD. He greeted them with smiles and enthusiasm. ‘Selam (Hello), selam, merhaba, welcome!’ he exclaimed as he shook hands with Louise and Carmen.

Abebe drove from the airport along hectic, crumbling roads. They saw beggars in rags alongside smart, brightly dressed men and women; lone barefoot children skipping through the dust and gravel thrown up by heavy trucks; well-groomed children walking hand in hand with parents; laden donkey carts alongside chauffeur-driven Mercedes; men driving scrawny goats beside six-axle trucks carrying cattle and produce to the city market. AK47-armed Derg soldiers were on every corner. As much as possible, pedestrians avoided them and wove their way among lorries, taxis and cars of every size, age, make, condition and colour. Throngs of people surged around temporary market stalls at roadside intersections. Petrol and diesel fumes filled the still, clammy air.

It was late afternoon, and the shops and roadside stalls were full of people bartering for food, fabrics and fuel: a conglomerate of humanity, some barely existing, others clearly enjoying the pleasures of the city. The two women saw starving people with cerebral palsy, handicapped people begging and limping along, while others sauntered into the few palatial restaurants to be welcomed at the door by uniformed maître d’s. These first visions caught Louise’s attention and heightened her emotions, especially when a gaunt, crippled boy begged at their car window as they stopped at an intersection. She felt helpless and realised how a traveller’s heart could harden when faced with such profuse distress.

In the city centre, they drove past the limestone St George’s Cathedral, Addis Ababa’s famous Orthodox Coptic church, with bold notices inviting worshippers to Meet your God. Louise stared as hundreds of worshippers kissed its perimeter walls, seeking blessings and answers to prayers.

‘They come every day, looking for cures for sickness, and confirmation of riches in heaven,’ said Abebe. ‘Cathedral’s locked at the moment for a priest’s prayer service, but there is still much to see in the grounds. If you like, I’ll stop, so you can take a closer look.’

He parked the 4WD in a side street. Louise and Carmen climbed down, tired, but keen to observe the rituals and customs of Addis Ababa’s faithful. The Coptic worshippers ignored them. People repeatedly kissed walls, stained with a million previous kisses, or knelt in devotion on adjacent paths and grass – anywhere they could find a space. They bought cheap amulets of St George with images of him and his lance on a fat white horse, and endlessly repeated an Old Testament mantra in Amharic: God is our heavenly Father and we will obey him. Hundreds, of all ages, stood or knelt. Abebe told Louise they were waiting for a sign that the Second Coming was near. Did these people really believe in the Second Coming? All this intensity, this level of devotion, was so unexpected – not what Louise had imagined or read about. She stood and watched these people, in their pleading and prayer.

Amid their mutterings, Louise thought of the once-a-week sedate Anglican worshippers at her home church in the Adelaide Hills, with people dressed in their Sunday best, thanking the vicar for his oft-repeated sermon about St Paul on the road to Damascus. Incredulous at what they were observing, Louise and Carmen walked away past street vendors and climbed back into the 4WD.

‘Nothing much will come of their prayers, but they’ll be back again tomorrow,’ Abebe said, as if to confirm his scepticism. ‘They are here every day; it’s been like this forever.’

They drove the last mile to the university campus, entering via high, imposing black wrought-iron gates; the university name was printed in metre-high letters on an adjacent stone wall. Once inside, they drove down a wide avenue of palm trees with well-tended flower beds, shrubs and lawns on either side. Beyond were picturesque features of the old formal Selassie buildings, set alongside hibiscus and bougainvillea. Further along the driveway and its many tangential paths, students sat in animated conversation; young men and women embraced in the shelter of pepper trees, while others stretched out, enjoying late afternoon sunshine.

‘Campus is a good place to be, very different from in the city,’ said Abebe. Louise and Carmen had to agree. This was an oasis compared to their first experiences of Addis Ababa. The 4WD swung past two-storey stone administration buildings and pulled up outside a prefab student accommodation block.

After introductions to other students, Carmen and Louise unpacked in a small, sparsely furnished bedroom with two single beds. At 5.30 pm it was still too early to go to bed, despite their tiredness from the long flight. Louise was buoyant, just as she had been when she first arrived in London. She was anxious to explore the campus. She put on close-fitting grey tracksuit pants with the Australian gold and green stripes on the legs and asked Carmen to go with her, but she declined, saying she needed to rest. ‘Louise, you never stop. Even now, when we haven’t slept for a day, you’re in your conquer-all, find-out-about-everything mood!’

‘I’ll just stretch my legs; I won’t be long, no more than half an hour.’

‘Enjoy yourself.’

The campus was vast and sprawling. It would be easy to get lost, Louise thought, as she followed signs pointing to the Department of Ethiopian Studies. She stood for a moment in order to get her bearings, unsure of which way to go. Ethiopia’s heritage was everywhere. She sensed the spectre of another time in this land as she saw more distant pillars at buildings’ entrances, stone-lined pathways and monuments: symbols of the Ras dynasty, and of the old Emperor Haile Selassie, ‘Elect of God’. She imagined him feeding his pet lions that apparently used to roam freely in adjacent grounds. Ethiopian life had changed irrevocably since the Emperor’s demise in 1974.

The campus was quiet except for the city traffic beyond the perimeter walls. Sighting further signs pointing to Ethiopian Studies, she strode on. Soon she was in front of a flight of wide stone steps leading to heavy, engraved double doors at the department entrance.

Feeling weary, her mood changed. She looked at the imposing stairway, then turned and walked slowly back the way she had come.

As she walked, she regained her usual confidence and decided to capture the effects of these first hours in Ethiopia in her notebook: the cool evening air in this high plateau city, the well-maintained Haile Selassie-endowed buildings, the contrasting shacks and poverty, the teeming people, uniformed Derg soldiers, the beggars and worshippers. As she walked she also recalled some of the finer points of articles in journals about Ethiopia and realised she needed to explore the creative lives of some of Ethiopia’s writers because, she believed, good literature reflected the lives and spirit of the people. Writers such as Abbe Gubennya and Mengistu Lemma, she had been told, held a mirror up to their society. She would read their work. She pushed on and arrived back at the hostel in time to join Carmen for an evening meal.

In London Louise was usually up by seven, but here everyone was afoot as soon as it was light. Each morning she was wakened by loud music and the cacophonous sounds of traffic. Abebe called on the first two mornings to take them on short tours of the city. On the first morning Louise watched the hazy sun as it broke free of the rooftops, causing shadows and splashes of bright light. People were already at work: hundreds of them, walking along with well-dressed children, presumably on their way to school. Some people sat on the kerbside, others sprawled on pavements around buildings and shacks. Abebe parked in a side street adjacent to an entrance to Addis Ababa’s huge Mercato Market.

They walked down the crumbling lane to the market entrance. Since Louise knew only a few words of Amharic, the comfort of Carmen’s company strengthened her resolve to communicate with stallholders. Carmen had spent six months in Kenya, but Louise had never been to Africa before and, despite her gap year in Italy, had rarely left the reassuring noises and patterns of Adelaide and London.

Stepping round street vendors, they entered the market. Abebe advised that it would be safest if, at least on this first visit, he accompanied them. While the rest of Addis Ababa symbolised a country establishing a fresh identity under the Derg, the timeless, noisy and vigorous Mercato Market remained unchanged. Louise was surprised at the labyrinth of streets and alleyways, the blacksmiths’ forges spewing smoke and flames, and the tanners sitting with piles of hides and fresh skins hung up to dry, still crusted with blood. There were men cutting rocks and others trimming vegetables, while aromas of spicy beef curries, fruit, vegetables and flowers, along with the smells of donkeys and goats, wafted over the stalls.

For the next hour, the three of them picked their way between stalls amidst the din of bartering chatter. The market’s tumult could be exhausting, but Louise felt joyous at the sight of the chaos and obvious vitality. Abebe suggested they stop for coffee. They sat alongside other customers eating spicy meats wrapped in injera, smelling the scent of incense burning. Everyone had warned them about the risks of wandering in Mercato but, in reality, walking alongside the noisy throng, they felt quite safe.

They left the market exhilarated; the taste and smell of coffee still with them along with the sights and sounds of Ethiopians plying their trades.

Ayzore – ‘Be Strong’

AFTER THREE DAYS of meeting fellow students and touring Addis Ababa, it was time to prepare for the first field trip. Louise and Carmen registered for the one-day pre-fieldwork course titled Anthropology and Health, introduced themselves to the department registrar and collected handouts giving general information about Addis Ababa and Ethiopian life. Louise read: Other than religion, it is agriculture and pastoralism that fill the days of well over 80 per cent of the country’s eighty million people. Literacy levels are still well below 50 per cent. Women are highly respected in Ethiopian society, but the same cannot be said for gays and lesbians. Homosexuality is not acceptable …

She continued reading: Medical anthropology that we promote is concerned with the relationship between Ethiopian cultural factors, and the nature and extent of health and disease … especially in isolated rural regions.

In the refectory she found her colleagues skim-reading the notes and discussing Ethiopia’s different cultural and language groups.

‘These notes are detailed,’ said Rosalind, an English researcher from Manchester.

‘It’ll take a few days, at least, to absorb all this,’ replied Carmen.

‘Yes, and there’s so much more to learn in the field,’ said Rick, an American anthropologist from Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins University, who had previously completed fieldwork in Ethiopia.

Louise listened as Rick told Bassam, who had just arrived from Jordan, about the major and minor Amharic and Oromo dialects which varied from valley to valley.

‘How long will it take us to learn to speak some Amharic when we are with village people?’ asked Horst, a tall, open-faced, blond student from Hamburg.

‘That depends on who you meet, and whether you can quickly establish trust. Most village people are very isolated. You’ll learn to communicate if you watch them closely, that’s my experience,’ advised Rick.

‘So we get the best results if we stay in the background, observing rather than asking too many questions too soon?’ asked Louise.

‘Yes, slow, steady and quietly persistent – that’s the strategy,’ said Rick. ‘Anyway, Dr Wolde will give you excellent advice. He’s a great teacher who knows the fieldwork sites better than anyone. You’ll be in good hands.’

‘Is Dr Wolde the author of these notes?’ asked Carmen.

‘Yes, he’s the author, and our fieldwork supervisor. I met him when he visited my uni – that’s why I grabbed the opportunity when this trip became available.’

‘What did you like about him?’ Louise asked.

‘He’s a good communicator and a brilliant researcher.’

Carmen said, ‘Just listen to his introduction: The people in isolated valleys have little experience of centralised government and essentially live in a conglomeration of hundreds of independent small towns and villages, each sharing the running of their own affairs among its men folk, according to title, age and occupation. I wonder what role women play in these villages?’

Louise knew from her readings that village women had significant domestic responsibilities. ‘Okay, here’s a reference to women’s roles,’ she said, reading from the notes: Women are largely responsible for the organisation of agricultural routines … and the many markets which help to bind villages and local regions …’

‘I can’t understand all this information,’ said Bassam, who was struggling with the handouts written in English.

‘Don’t worry,’ said Louise, ‘we’re all struggling to get the picture, but by the time we return I’m sure you’ll have as much Ethiopian wisdom and understanding as the rest of us – we’re no different.’ They all laughed, Bassam included.

‘Zeno Wolde will expect us to have read his handouts so we have some framework for our initial fieldwork experience,’ said Rick. ‘He will support us. He won’t let you fail.’ Rick directed this last remark to the apprehensive Bassam.

Louise had read about Ethiopian village life before leaving London. She was careful, though, not to express her knowledge too openly, especially among students she did not really know.

In their room that evening, Louise said to Carmen, ‘In a few days we’ll be in the field and with people whose language we don’t understand.’

‘You mean we’ll be thrown in at the deep end?’

‘Probably, but I don’t mind. According to Rick, we just need to merge with village people, appreciate their customs,’ said Louise. ‘And it’s the women we have to get to know. I’m sure they are the bedrock of Ethiopia’s society, but also the most oppressed.’

‘Isn’t that always the case everywhere? Louise, you amaze me. You walk around the city, read Wolde’s notes, recognise the influence of the saints or kiddus as you call them and, in a few hours, you provide a rationale as to why you want to spend time with people in the Southern Tribal Lands. How do you do it?’

‘Thanks, Carmen, but like everyone else I’m on a steep learning curve.’

‘Don’t I know it! Now, what do you understand by doomfata, or Fekkare Iyesus or debtera or even azmari?’ They both laughed.

Louise shared her concerns that the fieldwork would be demanding. Yet, she envisaged they would be at ease when they met village people and agreed with Carmen that no matter how well prepared they were, there would be pitfalls.

‘Yes,’ said Carmen, ‘I suppose there are always pitfalls – like catching giardia or even malaria.’

‘Are you afraid of catching a disease?’

‘Maybe, but I guess I’m not as confident as you about staying healthy in remote regions. There are plenty of people who have taken every precaution and still get malaria or cholera.’

Louise reminded Carmen of the Amharic expression Ayzore, which means ‘Be strong!’ It is a call of encouragement to Ethiopian women when they are in labour. And it’s also a call of encouragement when people walk from village to village over steep and rocky ground, just like, thought Louise, her grandmother’s advice that hardship could be endured.

‘My dad’s advice was to not get above yourself and things will be okay,’ said Carmen. ‘He’s a true Lancastrian, a foreman in a foundry, and that’s not getting above yourself.’

Louise remembered the hollow faces of women in photographs her London University supervisor Mike Boetcher had shown her – colour photos of mothers and babies waiting to be seen at a makeshift Médecins Sans Frontières clinic in Jinka, Southern Ethiopia, and of Ethiopians from Tigray and Amhara fleeing the famine-ravaged north; of decorated Hamar and Banna women at their open markets, Mursi women wearing lip plates, and aerial photos showing the vast Omo river valley. What strategies could she use to stop hunger for the Ethiopian peasants? How could she be practical?

‘You know,’ she said to Carmen, ‘it dawned on me a couple of days ago that anthropologists have to be like poets, and need to be accurate as well as compassionate about the people they describe.’

‘I like that … give me an example.’

‘What about Sylvia Plath’s poem ‘The Mirror’ – the first few lines tell us how we should proceed in the field.’

‘What does she say?’

‘Essentially she recommends we should be truthful and have no preconceptions about what we observe and record – don’t let love or dislike cloud your observations.

‘Yes, being truthful is important,’ said Carmen. ‘Louise, you are the only person who thinks that poets can contribute to scientific enquiry! Where do you get all these ideas from and what makes you so fearless?’

Early Life – South Australia

AFTER LOUISE DAVITT was born in 1962, her mother Monica sang lullabies as she rocked her infant daughter. Family members said the child inherited her mother’s temperament – gentleness, blended with steel. Louise’s father Gerald sang Mozart’s ‘Cradle Song: Sleep my Princess Oh Sleep’, and his daughter’s eyes would shine. As she grew older, he was impressed by her capacity to make decisions with calm, intelligent deliberation.

Louise and her older brothers, Geoff and Alex, spent school holidays on their paternal grandparents’ barley and sheep grazing property near Crystal Brook in South Australia’s mid-north. The children loved the creeks and birds and the ancient gnarled eucalypts. After winter rains the land was green, but in summer it baked to brown and yellow. Their grandparents had worked hard all their lives, solely to make ends meet; they never expected to be rich, and taught their son and grandchildren that hardship was a great leveller. Louise’s grandmother Margaret was a lifelong member of a local book club, while her grandfather Max supported the local football. They played tennis on their homemade tarmac court and regularly entertained friends in their battered hundred-year-old farmhouse. Often life was challenging but troubles never struck root for Louise’s grandmother.

Drought, low incomes, Margaret’s miscarriages and a stillbirth had affected the grandparents’ lives, yet Margaret Davitt could appraise and put into perspective the truth of what happened. In any situation, she was the family’s sounding board, observing events and asking, ‘Is this event good, bad or of no consequence? And where could it lead? And what effect would it have on the grandchildren, now and later?’

Margaret liked to play games of questions and answers. ‘I learn from listening to the stillness in life,’ she would say, ‘and then I enquire.’ Louise loved talking with her grandmother. She remembered how Margaret had once told her that she owed her health and resilience to the salubrity of fresh winter winds and summer’s hot breezes that prevailed in Crystal Brook.

‘Fortitude in the face of adversity, that’s your grandmother,’ her father often said. Louise knew how her grandmother’s ideals were distilled in memorable phrases:

Nothing to fear in life.

Hardship can be endured.

Everyone has talent.

True love is everlasting.

Her grandmother’s motto was to enjoy life and be happy in the moment. ‘Laugh much, and when you experience difficulty, pause, and think carefully before you make a decision.’ She told Louise that life’s journey was rarely straightforward, and she recognised that Louise was keen to travel and meet different people.

Louise’s father, ever tethered to practical matters, was no romantic. He too advised her how important it was to be able to adapt to setbacks, which were part of life’s merry-go-round.

On her grandparents’ farm, Louise ran through tall barley, walked for miles, gathered blackberries and native peaches called quandongs, fished for tiddlers in creeks, watched small trout twist and dive in the farm dam, climbed trees, built dens and learnt how summer’s burnt landscape would always recover by the next spring.

Since puberty, Louise’s features were admired: her broad brow, fine nose and full lips; her expressive, deep-set blue eyes; thick honeyblonde, shoulder-length hair; and her tall athletic body with long muscular legs. But she never flaunted her looks.

As a teenager with many friends, swimming and surfing at an Adelaide suburban bayside beach was a favourite pastime. They spent long days at the beach, their skin turning nut-brown. And it wasn’t long before she experienced young love. She knew the facts of life, had casual boyfriends but never slept with them, though occasionally she thought she would like to. At sixteen, her mother arranged for her to be prescribed the pill. Louise fell in love with a classmate friend, Luke, but they didn’t make love. However, with Rob Hardy things changed.

Rob was a first-year medical student whom she met while in her final year at high school. In the dunes at sunrise, below a cobalt sky, they experimented with and enjoyed their intimacy. Rob glowed in her company. They became a close couple. They sailed together across the Spencer Gulf in a friend’s racing yacht. Once they skydived above Strathalbyn: a gift from Louise to Rob on his birthday. Her family wondered if Rob and Louise would ever part. Her mother, observing them, said, ‘I think they’ll always be together.’ The two teased each other openly.

‘Your hair’s like a spiky echidna,’ she told him one evening at a family dinner after they had spent an afternoon at the beach. Rob laughed, and joked that this was the price he had to pay for spending so much time with Louise at the beach.

Alone together on an early summer evening, nestled in their dune resting-place, Louise stepped out of her shorts, knickers and t-shirt and raced Rob into the surf. Initially uncertain, Rob threw off his clothes and together they plunged into the lapping waves. Rob was excited at her desire. He held her by her waist; they kissed with salty lips and clung to each other. Louise arched back against him and Rob felt himself pushing into her amid the breaking waves.

Slowly they parted and swam out to deeper water, kissed again and held each other’s hands as they floated on the rolling waves, and waited for the waning of the day.

‘We’ll be like this forever,’ Rob whispered in her ear.

‘Yes, I know we will. If ever I go away,’ Louise said with a distant look, ‘I will always think of you, I promise you that.’

About to complete her first degree, Louise sat at her desk in a brightly decorated study-bedroom as a late-spring drizzle glazed her windows. The conclusion of this preparatory stage of her career was in sight. Focused, she had adopted her father’s adage: ‘Fortune favours the prepared mind’. Passion blended with intellect, her ideas gathered momentum. University staff and fieldwork supervisors were struck by the rousing quality of her seminar presentations and essays. Characteristically, she wrote, People die in their houses and in the bush amid cocoons of silence …

After four years she graduated with first-class honours in anthropology. The next step was to enrol for postgraduate studies in the joint schools of African Studies and Tropical Medicine in London, learn some Amharic and begin fieldwork studies in Ethiopia. ‘So here I am ready to leave,’ she murmured. She was excited but wondered what lay ahead, who she would meet, and where travel would take her.

Set now for London and separation from family and friends, there were farewells. It was going to be difficult to say goodbye to Rob. She’d known and loved him for nearly five years. At times they talked about doing great things together, travelling, having children and a family life. Rob always thought of Louise as his partner, an unusual, beautiful young woman. And now she was going abroad on an indefinite stay. He wondered whether Louise would forget their beautiful times together, the range of their common interests, the welcoming and love from each of their families. ‘To give all this up, for what?’

‘I’ll write to you,’ she said again as they embraced in the airport departure lounge.

Rob watched her ascend the aircraft steps, stop at the top, turn and wave then disappear. On the flight Louise’s thoughts were pulled in two directions, sadness at leaving, but also excitement and determination.

Louise was a keen letter writer. Her first November in London in 1984 had been surprisingly wet. Louise praised the grey clouds and the water that flowed from old leaf-filled gutters. She wrote home to her parents and her Adelaide boyfriend Rob about … steady rain and kettle drum sounds that herald advancing thunder across London. They excite me. She continued: The thunder can roar across London’s squares and often the torrential rain seems to me as if it could knock down buildings. And it’s fun when, as I ride, my wet hair becomes horizontal in the surging winds that often accompany the rain. She concluded: And you know, the mist when the rain ceases hangs over the river, like it’s all part of London life.

Her letters helped her family, Rob and other friends feel they were in London with her.

Meeting Zeno Wolde

THE FIRST GLIMPSE Louise had of the group leader Dr Zeno Wolde was in a draughty portable hut on the Addis University campus adjacent to the Ethiopian Studies building. As she sat waiting for the instructions, maps and timelines for the field trip in the Lower Omo Valley, a striking athletic man walked in. Louise was surprised; she hadn’t expected someone so startlingly sensuous, so unacademic and riveting. He introduced himself with a friendly confidence and air of authority. His language was clear and he appeared to have boundless energy, like a replenished mountain stream bubbling along before them.

‘What do you think?’ Louise whispered to Carmen before Zeno began his talk about what he expected of them.

‘Every one of us,’ Zeno began, ‘every one of us, I’m sure, has been moved by the history, geography and culture of rural Ethiopia – attracted here in one way or another, by watching film and television, by photos, or by reading books and research reports. Ask yourselves what has brought you here. Share your answers with me and your colleagues.’

Louise glanced at Carmen and was about to say something when Zeno asked again, ‘Why have you come to Ethiopia? Are you here because Ethiopia is considered to be the cradle of civilisation, or are you here because, at this time, Ethiopia is considered one of the poorest countries in the world and you want to see what poverty is like?’

No one responded. Zeno carried on. ‘Or is it our history that you want to explore and the fact that we are the only African country that has not been colonised? Or have you been provoked to try and understand the nature and extent of Ethiopia’s disastrous famines in 1974 and again in 1984, when over a million people starved to death?’

A deep hush enveloped the room. Zeno appeared despondent when he spoke about the famines. In one of his essays, part of which was in his introductory notes, he had suggested that decisions that people didn’t make, and events that didn’t happen – like improved education and agricultural practice – were largely responsible for the famines. Louise recalled reading that Zeno had hiked across the country and lived with peasant people and knew their history.

‘Don’t be frightened to ask questions. Interaction is essential. That’s what we’re here for.’

They were unsure how to respond. Zeno noticed Louise looking at him. He looked at her, a head-to-toe gaze. He liked what he saw and found himself face-to-face with a young woman of allure. Louise was conscious of his gaze.

Because of Zeno’s interested stare she floundered a little. ‘This is a general question,’ she said nervously. But then, encouraged by his smile, her self-assurance returned. ‘What are your priorities for us and on which particular areas will we focus?’

‘Okay, that’s a good question,’ he said, looking directly at Louise. He explained that while his overall fieldwork priorities were in the far south in the Omo Valley, he would begin by taking them to rarely visited settlements in a valley below the Bada Ridge to the south-east of Addis Ababa. He wanted to provide a contrast with the nomadic tribes of the south. As he spoke, he pointed to places on a large wall map.

‘Your priorities are to observe and record conditions that influence the physical and emotional health of isolated rural populations. Respect and enjoy these people. Remember, being among them is a privilege. That thinking will reward you. Think of yourselves as explorers. In your notebooks, record images, ideas, and if possible snatches of dialogue to paint unique pictures. Make sure your notebooks are always within reach. Record small details about people’s homes, the landscape around their homes, what they are wearing, what they eat and drink, and relationships between men, women and children. Record whether you think a village is holding together, or because of the famine is about to unravel. Find out about the origins of the village. Listen to the people. Be patient. Date your notes. And above all, try to think of yourselves as cameras and help readers to feel as if they are there with you. To begin with, observe a whole village, then focus on detail, and generate life from that detail. I want you to shake up people’s perceptions of Ethiopian rural life. My notes and references should help. Are there any questions?’

‘Wow, what a performance,’ Carmen whispered to Louise. ‘What are we supposed to ask him after that? He reminds me of Brutus in Julius Caesar imploring from the pulpit … Countrymen and lovers! hear me for my cause, and be silent, that you may hear … awake your senses.’

‘That’s brilliant, Carmen.’

‘Thanks, the quote just came to me. It seemed appropriate. We used to have to learn chunks of Shakespeare like that in my high school English classes.’

‘You’ve caught his mood and high expectations for us.’

‘I don’t know if I will fulfil his expectations, but I like him,’ said Carmen.

No one asked Zeno a question. They remained in awe of his zeal for promoting the uniqueness and value of Ethiopian rural life – people of another world, he had called them.

Zeno smiled and continued, expecting the students to adopt his enthusiasm and commitment. ‘We will drive south-east from Addis to Mojo and then Nazret. Then we’ll take a track to Sodere, so that you can see the settlements in the Awash River Valley. If reports of the roads to Asela and to Kofele are satisfactory, we’ll explore the villages below the Bada Ridge.’

These names and places were just dots on a map to the students. A yawning gap existed between Zeno’s life experiences and those of the bright but inexperienced students. He didn’t expect them to bridge it in a few short weeks but wanted them to become involved with village people. He wondered whether any of them had the passion and commitment he expected.

‘Our goal is to reach Jinka, the main town in the lower Omo. We’ll stay there and, if time permits, we’ll visit the small Hamar towns of Turmi and possibly Dimeka, on the border of the Hamar and Banna tribes. There you’ll experience the tribal markets.’ Zeno’s face lit up with enthusiasm. ‘You will find all these places on the maps in your fieldwork packs. We’ll be away for three weeks.’

Louise hoped that Zeno Wolde would support her, introduce her to significant people and help find references for her writing, so she could return to London and Adelaide as an ambassador for some of the poorest but most resilient people in Africa.

She recalled that Ambassador, in its original English definition, was: a messenger sent on a mission to represent a country or people. Was this what Zeno Wolde expected of his students? Would Louise Davitt, Carmen Smith or even Bassam Hashoud become messengers in their writing and advocacy?

Driving South

IT WOULD TAKE six or seven hours to reach their campsite just south of Sodore. Five people in the first 4WD were Abebe the driver and camp cook, Louise, Carmen, Horst from Hamburg, and Zeno. Degu, a part-time driver, drove the second 4WD containing four more students. The loaded vehicles moved at varying speeds as they wound through early morning Addis traffic. Abebe sounded the horn continually to avoid donkeys, horses, goats, pedestrians and other vehicles.

Then they reached the open road and dusty plains which sloped away to gaunt etched hills above Debre Zeyit. Even farmers less than a hundred miles from Addis struggled to harvest meagre, shrivelled crops. Louise stared at the barren and often stony landscape, noticing every bend in the road, every small child herding goats, every field and distant village. Although she’d read about rural Ethiopia, she now realised the scale of the country could be overwhelming. The riddle of Ethiopia’s splendour, harshness, deprivation and opportunity was before her.

‘And here we are, less than two hours drive from Addis, and we see all this,’ she said to Carmen.

‘It’s bad enough when you read about famine in the papers, but when you come face to face with drought and such obvious poverty,’ Carmen said, ‘that really brings it home to you. It’s like being reminded of Dimbleby’s BBC documentary at Korem in Tigray all over again. Remember that?’

‘Yes, most people who saw the film thought starvation just happened in a faraway country.’ Louise was realistic.

As they drove they watched the early morning sun glow on hillsides and nearby mountains, on the narrow dusty roads in need of repair, on fields with acacia bushes, stunted trees and savannah grass. They saw smoke from distant villages rising in columns. Zeno told them stories in clear accented English, punctuated with Oromo and Amharic names of places and people. Louise, Carmen and Horst listened, captivated by his zest as, with a flourish of his hands, he related the life and history of the landscape and its people.

Louise whispered to Carmen, ‘If you wanted to choose an Ethiopian tour guide, no one could be better than Zeno Wolde. Aren’t we lucky?’

They gazed at fields with heaped stones, thorn bushes, drooping crops and distant farm workers harvesting maize and sorghum. Louise stared, trying to absorb the glare, the delight and also the harshness of a farmer’s day. She wondered whether they would continue farming as their forebears had done, and just accept drought, either surviving their short harsh life or dying where they worked.

Or perhaps change would come to this place, where the sun rises slowly and the morning mists and brief drizzle dampen village gardens.

A Roadside Stop

AFTER NEARLY THREE hour’s driving, Zeno called a halt. ‘Okay, Abebe, pull over and stop at that gravel space just ahead.’

Minutes later, the second 4WD pulled up. They were glad to stretch their legs and have a break. Everyone gathered around Zeno. He suggested the students find seats on the rocks next to the vehicles. If they needed to relieve themselves then the bush behind them was appropriate.

They sat on rocks, their feet apart on the gravel for balance. Water bottles were passed round. Zeno placed himself in the middle of the group. He wore a necklace with a beautifully carved dark wooden cross which seemed out of place for a man who presented such an animist and radical view of his country. In this roadside setting, as in the lecture theatre, he was a natural one-man show. He quickly altered topics in a conversation as his stream of thought was diverted by the landscape, or by a student’s grimace or smile. Given the cross he was wearing, they were not surprised when he told them that it was impossible to avoid religion here. ‘Ethiopia,’ he said, ‘was originally an ancient kingdom with Christianity in its Coptic form as the official religion.’

In this isolated roadside stop, looking towards the light and shadow of the wooded valley below, they listened intently. Zeno didn’t expect they would be quiet for long. The blonde Australian woman would be sure to ask questions.

‘Ethiopian people, even remote, poor people, are very religious, but they also know how to enjoy themselves,’ he said. ‘Enjoyment can also be a religion, you’ll see.’

Carmen chewed her lip, and in her Lancashire accent, spoke up. ‘Tell us how religion can be enjoyed?’

He paused before replying. ‘I want to tell you that although I am not religious, I respect those who are, especially as their beliefs have often helped them to survive difficult lives. And their beliefs, particularly Ethiopia’s Coptic Christian beliefs, have existed here since earliest times, and at least since the tenth century.’

Carmen nodded but Louise knew she was an atheist and was still holding to her scepticism.

‘Although there are Muslim villages here, as in Afar, generally the villages of this region and, of course in the north in Amhara and Tigray, are places of passionate Christianity with many religious festivals and happy occasions. People believe that when there is suffering, as in the famines, eventually their God will relieve them and plentiful times will return. This attitude is at the core of their optimism.’

‘Were they still optimistic during the recent famine?’ asked Horst.

Zeno shrugged, eyes narrowing. ‘During the famine, of course not, but you’ll find proof on this trip that when the famine ended, the Ethiopian people quickly recovered their spirit. Pessimism is the real enemy; it can rot and destroy the fabric of village life.’

Louise felt her face flush with admiration for Zeno’s passion. She watched the way he gestured as if his whole body spoke about the famine and its aftermath.

Zeno talked about his long embrace of Ethiopia’s people, extolling one tribe, one family group, one small farm after another, alluding to different cultures, dress, language and history. The students listened intently.

‘You’ll no doubt face scenes that could be unpleasant. Poverty, by Western standards, is everywhere in Ethiopia, particularly out here. You will have to cope with seeing many unpleasant scenes. Ethiopia’s rural poor are very poor. Many people think they’re just backward, but these are outstanding people who make significant contributions to their community. Try and think like that. There is much to see and admire – village people will welcome you.’

‘Dr Wolde,’ Louise said, ‘it has taken you years to identify closely with the native people of Ethiopia, so what do you expect of us on this short visit?’

He looked at her warily. ‘My best advice is, spend time with these people, accept them as equals and note their traditions. Tradition is important for them. They have much to teach us. And their lives won’t change quickly, especially in isolated villages.’

Zeno explained how tribal elders, steeped in tradition, did not contemplate changes to their way of life. ‘But,’ he said, ‘some younger people are on the move, mostly to try and get work in the cities. Movement of people signals change, however minor. Ultimately they will judge what’s best for their community.’ Then he added, ‘Especially now the famine is almost over.’

The group remained sitting on the rocks, chatting among themselves, with a slight breeze rustling leaves. Zeno emphasised how they needed to live among village families, share with them and chronicle their lives. Louise thought about her Australian Aboriginal friend Mandy Watson and how through her dot paintings and Dreamtime stories she was able to recall the lives of her ancestors.

At this point, as the morning sun began to warm them, Zeno said they should continue their journey. They rose, stretched their legs and climbed back into the vehicles.