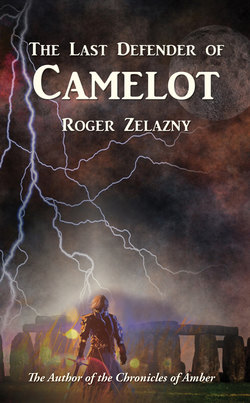

Читать книгу The Last Defender of Camelot - Roger Zelazny - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Last Defender of Camelot

The three muggers who stopped him that October night in San Francisco did not anticipate much resistance from the old man, despite his size. He was well-dressed, and that was sufficient.

The first approached him with his hand extended. The other two hung back a few paces.

“Just give me your wallet and your watch,” the mugger said. “You’ll save yourself a lot of trouble.”

The old man’s grip shifted on his walking stick. His shoulders straightened. His shock of white hair tossed as he turned his head to regard the other.

“Why don’t you come and take them?”

The mugger began another step but he never completed it. The stick was almost invisible in the speed of its swinging. It struck him on the left temple and he fell.

Without pausing, the old man caught the stick by its middle with his left hand, advanced and drove it into the belly of the next nearest man. Then, with an upward hook as the man doubled, he caught him in the softness beneath the jaw, behind the chin, with its point. As the man fell, he clubbed him with its butt on the back of the neck.

The third man had reached out and caught the old man’s upper arm by then. Dropping the stick, the old man seized the mugger’s shirtfront with his left hand, his belt with his right, raised him from the ground until he held him at arm’s length above his head and slammed him against the side of the building to his right, releasing him as he did so.

He adjusted his apparel, ran a hand through his hair and retrieved his walking stick. For a moment he regarded the three fallen forms, then shrugged and continued on his way.

There were sounds of traffic from somewhere off to his left. He turned right at the next corner. The moon appeared above tall buildings as he walked. The smell of the ocean was on the air. It had rained earlier and the pavement still shone beneath streetlamps. He moved slowly, pausing occasionally to examine the contents of darkened shop windows.

After perhaps ten minutes, he came upon a side street showing more activity than any of the others he had passed. There was a drugstore, still open, on the comer, a diner farther up the block, and several well-lighted storefronts. A number of people were walking along the far side of the street. A boy coasted by on a bicycle. He turned there, his pale eyes regarding everything he passed.

Halfway up the block, he came to a dirty window on which was painted the word READINGS. Beneath it were displayed the outline of a hand and a scattering of playing cards. As he passed the open door, he glanced inside. A brightly garbed woman, her hair bound back in a green kerchief, sat smoking at the rear of the room. She smiled as their eyes met and crooked an index finger toward herself. He smiled back and turned away, but . . .

He looked at her again. What was it? He glanced at his watch.

Turning, he entered the shop and moved to stand before her. She rose. She was small, barely over five feet in height.

“Your eyes,” he remarked, “are green. Most gypsies I know have dark eyes.”

She shrugged.

“You take what you get in life. Have you a problem?”

“Give me a moment and I’ll think of one,” he said. “I just came in here because you remind me of someone and it bothers me—I can’t think who.”

“Come into the back,” she said, “and sit down. We’ll talk.”

He nodded and followed her into a small room to the rear. A threadbare oriental rug covered the floor near the small table at which they seated themselves. Zodiacal prints and faded psychedelic posters of a semireligious nature covered the walls. A crystal ball stood on a small stand in the far corner beside a vase of cut flowers. A dark, long-haired cat slept on a sofa to the right of it. A door to another room stood slightly ajar beyond the sofa. The only illumination came from a cheap lamp on the table before him and from a small candle in a plaster base atop the shawl-covered coffee table.

He leaned forward and studied her face, then shook his head and leaned back.

She flicked an ash onto the floor.

“Your problem?” she suggested.

He sighed.

“Oh, I don’t really have a problem anyone can help me with. Look, I think I made a mistake coming in here. I’ll pay you for your trouble, though, just as if you’d given me a reading. How much is it?”

He began to reach for his wallet, but she raised her hand.

“Is it that you do not believe in such things?” she asked, her eyes scrutinizing his face.

“No, quite the contrary,” he replied. “I am willing to believe in magic, divination and all manner of spells and sendings, angelic and demonic. But—”

“But not from someone in a dump like this?”

He smiled.

“No offense,” he said.

A whistling sound filled the air. It seemed to come from the next room back.

“That’s all right,” she said, “but my water is boiling. I’d forgotten it was on. Have some tea with me? I do wash the cups. No charge. Things are slow.”

“All right.”

She rose and departed.

He glanced at the door to the front but eased himself back into his chair, resting his large, blue-veined bands on its padded arms. He sniffed then, nostrils flaring, and cocked his head as at some half-familiar aroma.

After a time, she returned with a tray, set it on the coffee table. The cat stirred, raised her head, blinked at it, stretched, closed her eyes again.

“Cream and sugar?”

“Please. One lump.”

She placed two cups on the table before him.

“Take either one,” she said.

He smiled and drew the one on his left toward him. She placed an ashtray in the middle of the table and returned to her own seat, moving the other cup to her place.

“That wasn’t necessary,” he said, placing his hands on the table.

She shrugged.

“You don’t know me. Why should you trust me? Probably got a lot of money on you.”

He looked at her face again. She bad apparently removed some of the heavier makeup while in the back. room. The jawline, the brow . . . He looked away. He took a sip of tea.

“Good tea. Not instant,” he said. “Thanks.”

“So you believe in all sorts of magic,” she asked, sipping her own.

“Some,” he said.

“Any special reason why?”

“Some of it works.”

“For example?”

He gestured aimlessly with his left hand. “I’ve traveled a lot. I’ve seen some strange things.”

“And you have no problems?”

He chuckled.

“Still determined to give me a reading? All right. I’ll tell you a little about myself and what I want right now, and you can tell me whether I’ll get it. Okay?”

“I’m listening.”

“I am a buyer for a large gallery in the East I am something of an authority on ancient work in precious metals. I am in town to attend an auction of such items from the estate of a private collector. I will go to inspect the pieces tomorrow. Naturally, I hope to find something good. What do you think my chances are?”

“Give me your hands.”

He extended them, palms upward. She leaned forward and regarded them. She looked back up at him immediately.

“Your wrists have more rascettes than I can count.”

“Yours seem to have quite a few, also.”

She met his eyes for only a moment and returned her attention to his hands. He noted that she had paled beneath what remained of her makeup, and her breathing was now irregular.

“No,” she finally said, drawing back, “you are not going to find here what you are looking for.”

Her hand trembled slightly as she raised her teacup. He frowned.

“I asked only in jest,” he said. “Nothing to get upset about. I doubted I would find what I am really looking for, anyway.”

She shook her head.

“Tell me your name.”

“I’ve lost my accent,” he said, “but I’m French. The name is DuLac.”

She stared into his eyes and began to blink rapidly.

“No . . . ” she said. “No.”

“I’m afraid so. What’s yours?”

“Madam LeFay,” she said. “I just repainted that sign. It’s still drying.”

He began to laugh, but it froze in his throat

“Now—I know—who—you remind me of . . . ”

“You reminded me of someone, also. Now I, too, know.”

Her eyes brimmed, her mascara ran.

“It couldn’t be,” he said. “Not here . . . . Not in a place like this. . . . ”

“You dear man,” she said softly, and she raised his right hand to her lips. She seemed to choke for a moment, then said, “I had thought that I was the last, and yourself buried at Joyous Gard. I never dreamed . . . ” Then, “This?” gesturing about the room. “Only because it amuses me, helps to pass the time. The waiting—”

She stopped. She lowered his hand.

“Tell me about it,” she said.

“The waiting?” he said. “For what do you wait?”

“Peace,” she said. “I am here by the power of my arts, through all the long years. But you—How did you manage it?”

“I—” He took another drink of tea. He looked about the room. “I do not know how to begin,” he said. “I survived the final battles, saw the kingdom sundered, could do nothing—and at last departed England. I wandered, taking service at many courts, and after a time under many names, as I saw that I was not aging—or aging very, very slowly. I was in India, China—I fought in the Crusades. I’ve been everywhere. I’ve spoken with magicians and mystics—most of them charlatans, a few with the power, none so great as Merlin—and what had come to be my own belief was confirmed by one of them, a man more than half charlatan, yet . . . ” He paused and finished his tea. “Are you certain you want to hear all this?” he asked.

“I want to bear it. Let me bring more tea first, though.”

She returned with the tea. She lit a cigarette and leaned back.

“Go on.”

“I decided that it was—my sin,” he said. “with . . . the Queen.”

“I don’t understand.”