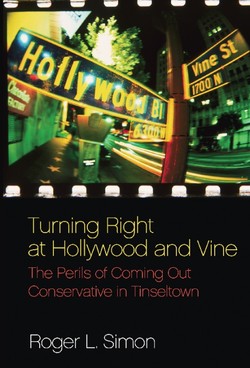

Читать книгу Turning Right at Hollywood and Vine - Roger L. Simon - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction:

MY OLD LIFE CALLS MY NEW LIFE

I was sitting at my desk, staring at my cell phone, for a moment uncharacteristically unable to speak.

“Hello . . . this is Roger Simon, isn’t it?”

“Yes, yes,” I blurted out, my throat tightening as it hadn’t in years. I felt a similar pressure in my chest, and my palms were sweaty.

Like a ghost from the past, my old life was calling my new life.

This was all happening on a typical chaotic June day at Pajamas Media—the burgeoning conservative new media company where I am the largely accidental CEO.

When the phone rang, I was watching a group of Tea Party activists being videoed in our studio while answering an email from an editor about a terrorist financing story and working with a writer on an investigation into Justice Department bias under Obama.

A woman identified herself as being from the Credits Department of the Writers Guild of America, the union of motion picture and television writers of which I am a member. I immediately assumed she was going to ask me, as they sometimes do, to participate in an arbitration—a service professional screenwriters perform anonymously, reading reams of their peers’ work to determine who receives the writing credit on a movie when more than one writer worked on the film. In the old days of Hollywood, those credits were often awarded arbitrarily to the producer’s brother-in-law or, more likely, his mistress. But the Guild objected and, after years of collective bargaining, won the right for writers to make the determinations themselves. It was a good thing, but I was having no part of it this day. I was way too busy to read a pile of scripts.

But before I could demur, my old life, as I said, called my new life. “Are you the Roger Simon who wrote The Gardener?” she asked.

“Yes,” I acknowledged, feeling immediately suspicious. This was 2010. The Gardener was a screenplay I wrote in 1989—twenty-one years ago! Were they trying to bill me for something? This was a union, after all. “What’s this about?”

“We want to inform you that it is in production,” she replied. In production? A twenty-one-year-old screenplay? That was unheard of. Most screenplays don’t make it past the studio shredders for three or four years, let alone twenty-one. Was someone playing a joke on me?

“Are you sure?” I asked.

“Yes. They began principal photography two weeks ago.” Two weeks ago? They were already shooting. Why hadn’t anyone told me? This was my original screenplay, my idea. It would have been a common courtesy for the producer or someone (the studio? director?) to call, other than the Guild.

But then I almost instantly remembered—this was Hollywood. Common courtesy is the last thing on their minds.

Especially common courtesy toward me. Because I wasn’t one of them anymore. I was an apostate. After decades as a liberal, super liberal really, I had gone over to the dark side, the conservative side—or conservative to them anyway, in a world where anyone to the right of Jerry Brown was second cousin to Attila.

As I hung up, though, I started to become excited. I was having a movie made again. I was being reborn, in a sense. Hollywood does that to you. It’s a like a fever or, more precisely, a virus, the kind of virus that you never lose entirely once contracted, a form of mono that doesn’t go away but lingers in the body to strike again when you least expect it.

I started to fantasize. Would this be my second Academy Award nomination? (My first, for Enemies, A Love Story, ironically came in that same distant year I wrote The Gardener: 1989.) I was already getting a swelled head. The Gardener—the story of a Mexican illegal alien gardener whose truck is stolen and who is forced, since he is not a citizen, to get it back by himself—was a serious art film with a disadvantaged minority protagonist. Just the kind of movie the Academy loved. Moreover, in this case, the exact disadvantaged minority was even more timely than it was in 1989. Immigration problems were all over the news in 2010. The film would be right up the Academy’s alley. Nomination? Maybe I would even win the Oscar.

Of course, I would need screenplay credit first. Undoubtedly, there would be an arbitration, only for this one I would be the subject, not an arbitrator. I had been in that position once before for the Richard Pryor movie Bustin’ Loose, so had some idea of the process.

Several writers who wrote after me would be competing for credit. I immediately dismissed one of them—the redoubtable Cheech Marin of Up in Smoke fame, who in the early Nineties had been hired to rewrite my screenplay and to star and direct in it. To put it kindly, an art film in the Italian neorealist style, as The Gardener was, was a bit outside Cheech’s comfort zone.

The next writer was Leon Ichaso, someone briefly employed to undo Cheech’s smoke-filled mishmash and return the script to my original conception. He would not be in the hunt either because he had made no particular contribution of his own. The fourth writer, a man named Eric Eason—who had written the shooting script that got the green light—would of course be competition.

A couple of weeks later, I read Eason’s script. It was well done, I had to admit. He had taken my work and brought it forward into the atmosphere of the LA Chicano/Mexican gangs of our time. He had even, to some degree, improved upon my original, deepening the story’s key relationship between Carlos—the gardener—and his teenage son Luis, who is being romanced by the gangs.

The film was being directed by Chris Weitz, who made About a Boy with Hugh Grant and later New Moon, one of the Twilight series. The latter, a vampire film, was clearly not Oscar material, but it made a fortune, more than any movie I had ever been involved with, and they were spending more than ten million dollars on The Gardener, a healthy budget for a tiny “specialty film” shot in East LA.

The Gardener seemed a force to be reckoned with, and I wanted to be part of it. Moreover, I had been involved with the movie not once, but twice before. In 1998 I had polished my original script with the actor Andy Garcia, who wanted to play the lead. At that point, I was going to direct. It was close to being made then, but, as often happens with independent productions, the financing fell through. I felt I more than deserved screenplay credit when it was finally produced. And the Writers Guild credit rules, I knew, were biased in favor of the writer of an original, as this was.

And yet something troubled me in all this. A reality nagged at me even as I lusted after renewed Hollywood fame and fortune.

The truth was, another me had written this movie.

Between the time I conceived The Gardener and its actual production, my life had turned upside down. The youth who had been a loyal foot soldier in the leftist movements of the Sixties and Seventies—going so far as to help finance the Black Panther breakfast program as a young Hollywood screenwriter—had begun to change during the OJ Simpson trial and then, when the jets flew into the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, continued past the point of no return. I had morphed into something of a cross between a neocon and a libertarian—if such a thing were possible—sympathetic to tea parties and many, if not every, political viewpoint I had once abhorred.

Whatever I was, I was no longer anything close to the liberal lefty who wrote The Gardener. And my transition had not been quiet. It had been entirely public, first through a blog I began in 2003 and then through the founding of Pajamas Media and its subsidiary PJTV, all with millions of readers and viewers.

In fact, I no longer believed wholeheartedly in the themes of The Gardener and was apprehensive about how the movie would be interpreted and whether that interpretation would be identified with me. Although I have great empathy for the plight of poor illegal aliens like Carlos, the hero of the film, and always will, I had become a firm believer in secure national borders, including a fence, and an enforceable immigration system that treats all equally. Carlos’s story—one of an impoverished but noble Mexican put in the humiliating position, because he is not a citizen, of having to steal back his own stolen truck—could easily make The Gardener a rallying point for the extreme left of the immigration issue, for open borders or even for no border at all. It was a film La Raza could love.

And oddly enough, I would be the one most likely put in the position of defending it. Normally, screenwriting is a relatively anonymous—if occasionally high-paid—occupation, but my role as CEO of Pajamas Media, appearing frequently on conservative talk radio and cable TV, made me anything but. I was a natural target for gleeful liberal reporters who would be happy to nail me for hypocrisy in my current position or for making an obviously ambivalent defense of a movie I once wrote, a capital offense in Hollywood.

Still—call it blind ambition, greed (there was a six-figure production bonus involved) or a natural competitive instinct—I went ahead with the arbitration. I read the drafts by the various writers and crafted the required three-page typed statement detailing, according to the rules in the Writers Guild Credits Manual, the reasons I should have the credit. One of those rules specified that as the writer of an original screenplay, I must at least share the story credit on the movie. But I lobbied for the whole thing, the credit of credits, the vaunted “Written By.”

I didn’t get it. The three-person committee of my peers voted to give the screenplay credit to Eason and the more obscure story credit to me. For a moment, I wondered if there was bias involved. These arbitrations make the pretense of being anonymous, identifying the competing screenwriters as A, B, C, etc., to the arbitrators. But five minutes on Google would reveal the writers’ real identities to anyone interested. (In the case of The Gardener, it would require even less, since the film was the subject of a prominent production write-up in the New York Times that named Eason and me.)

Had the arbitrators been biased against me because of my political views, now well known among the Hollywood community? Should I protest their decision? (There was a process for this.) I ventilated this matter with my wife, Sheryl Longin, also a screenwriter (Dick), and she reminded me that, bias or not, I was lucky to have lost the arbitration for reasons I already knew. For me to be a representative, maybe the representative, of The Gardener and all it might or might not stand for would be a potential nightmare. I could end up betraying myself or, worse, muzzling my reaction as others attacked me publicly. Better to enjoy the obscurity of a minor credit, she said. The money, and whatever acclaim there might be, wasn’t worth it.

Wives, of course, know best, so I never did lodge that formal protest. But the drama surrounding The Gardener had a deeper impact on me, because it got me thinking again about the larger subject of this book: the role of politics in Hollywood, and, consequently, in my own life. I started out as a pretty typical product of my generation—a New York Jewish boy enamored of the New Left—and turned into something quite different. A great deal of this narrative is about how I came to believe what I did and then how I changed, mostly against the background of the movie and publishing industries, not to mention a few bumps along the way with some nefarious political figures like the Sandinistas and the KGB. (I also wrote left-wing detective novels.)

Change is a mysterious thing, of course, and we rarely fully grasp the reasons for it. People are bombarded by the same stimuli and react differently all the time. After 9/11, many extreme liberal types became instant patriots but then over the years reverted to their original stance, now euphemistically called “progressive.”

I didn’t. I stayed the course and became lumped with that small group known as Hollywood conservatives, although I never liked political nomenclature or to define myself ideologically, even when on the left.

So are conservatives discriminated against in Hollywood, as is widely assumed? Well, yes. And you will hear much more about that later in this book. But I will issue a caveat. It’s important to remember that everyone is discriminated against in Hollywood. It’s not a career for the fainthearted or the naïve. And to dwell on how you are discriminated against can be just as self-destructive in the entertainment industry as it is elsewhere. The answer to bias of this sort is action. Go write a movie or a play with your views and get it produced. I know it’s tough, but it’s tough for everyone, especially now. A minute spent bellyaching is a minute not spent doing something about the situation, a minute not spent creating change. And at this moment in history, change (not the Obama kind) is happening very rapidly. Hollywood is lagging behind. This provides an opportunity for conservative and libertarian-leaning artists to be daring. The audience, if not the industry, is waiting.

In recent years, many in Hollywood hid their conservatism for business reasons. I think that was particularly difficult for writers. If you are any good, you write what you are. You can’t really deceive your employers, the public, or yourself and expect to produce anything of value. So you might as well not disguise your views. I imagine that was part of what prompted David Mamet to come out as a conservative on the pages of the Village Voice. Others are coming out of the proverbial woodwork: actors, directors, writers and producers. We are in a time of transition. Being liberal isn’t quite as hip as it once was. Libertarians may even be the cool guys now—or becoming so.

This doesn’t mean you parade your ideology in your creative work. Good writing and good filmmaking abjure propaganda. But art has a point of view, and it usually is the one of its creator, no matter what the deconstructionists say. To the small extent that The Gardener, when it appears sometime in 2011, is my creation, its author will be the Roger Simon of 1989, not of today. I genuinely wish its real creators—writer Eric Eason, director Chris Weitz, and producer Paul Witt—the best.

The Roger Simon of today has moved on and is finishing, with his wife, a stage play called The Party Line. Set in Moscow of the 1930s and Amsterdam of recent times, it has a mixture of fictional and real characters, including Walter Duranty, the infamous New York Times reporter who won the Pulitzer for deliberately misreporting Stalin’s forced starvation of Ukrainians; and Pim Fortuyn, the gay libertarian who nearly became prime minister of Holland before being assassinated by an animal rights activist. The theme of the play is political change, how and why it happens—a subject that has obsessed me for some time and will continue to obsess me, I suspect, for a while to come. It’s really why I wrote this book.

To see where I—and especially Sheryl—have arrived with this theme artistically, you will have to wait for the production of The Party Line.

To see where I began, turn the page.