Читать книгу Land Girls: The Homecoming: A moving and heartwarming wartime saga - Roland Moore - Страница 9

Chapter 4

Оглавление“Ah, doesn’t she look like Betty Grable?”

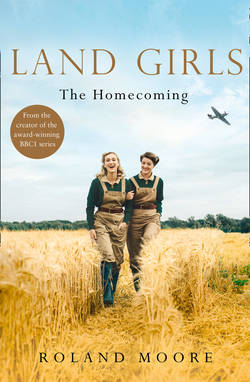

Finch giggled as he looked at the picture of Connie in The Helmstead Herald. Connie winced in embarrassment. The photograph showed her with the girl Margaret Sawyer, Connie’s soot-smeared smile a mix of bemusement and shock at the events that had just occurred. A streak of dirt ran down the side of Connie’s face. Margaret was looking sullenly at the camera, wrapped in her blanket, clearly not quite registering what was happening.

“I think I’ll pin this up in the kitchen to inspire the rest of you lot,” Finch announced to the room. Connie and Joyce were drinking tea, waiting for lunch, along with their fellow Land Girls young Iris Dawson and new arrival Dolores O’Malley. The kind-hearted warden, Esther Reeves, was standing at the stove stirring a huge pan of parsnip soup.

“No, you blinking won’t,” Esther stormed.

“Why not? It’s my kitchen,” Finch replied.

“’Cos it’s me what spends most time in here. No offence, Connie, love. It’s just I don’t want to be reminded about that awful crash all the time.”

Connie couldn’t blame her. The train crash had resulted in four casualties – including the young soldier who’d been trying to roll a cigarette. And over twenty other people had ended up in hospital with various injuries. Connie didn’t want to be reminded of it either.

“I’ll put it away, then,” Finch grumbled. “Still who’d have thought? She might get the George Cross for this, you know.”

“You’re making me cross,” Esther said, throwing him a look. Finch knew when it was best to let things drop. He pulled himself out of his chair at the head of the farmhouse table, took the newspaper and left the room.

“Also he’s brought seven copies of the thing,” Esther whispered to the girls. “He’s more proud of what you’ve done, Connie, than anything his own son ever did. Tragic, really.”

Connie felt awkward. She broke the tension by asking when the soup would be ready. Esther checked the taste one final time, indicated her approval and asked for Joyce to pass her the bowls. She ladled out the hot soup and handed it around. Dolores gave everyone a chunk of potato bread for dipping and everyone sat eating in hungry and appreciative silence. It would fill their bellies for the afternoon of digging ahead.

Connie had had enough of the photograph and the article to last her a lifetime. The newspaper had only come out yesterday but already Henry had talked about getting it framed and putting it on the wall somewhere in the vicarage. He was trying to patch things up after their recent arguments and she was touched by his efforts. Especially as she’d seen the way he’d grimaced when he’d read that she’d used her maiden name in the article.

“I just said it out of habit,” she offered weakly. It was some relief that Henry didn’t want to talk about it. With tight lips, he said it didn’t matter, when it obviously did. Connie wanted to explain. But what could she say? She used her maiden name out of habit? Because it felt more comfortable? Because she was subconsciously wondering if one day she’d go back to it?

Instead he’d busied himself with celebrating his wife’s heroism. But then he’d let slip something that perhaps made everything worse again –

“This will convince people you’re not just out for yourself,” he’d idly said.

Connie shot him a look as he instantly regretted his choice of words; wishing he could somehow suck them back in.

“Who’s saying I’m out for myself?” Connie had stormed.

“Well …”

Henry was forced to sheepishly admit that some of his older parishioners weren’t very charitable in their views of his wife. They were suspicious of Connie’s motives in marrying the young vicar. They spoke disapprovingly about her past, even though they knew nothing about it and were making most of the supposed ‘facts’ up. Connie immediately knew the people he was talking about.

“It’s those three old biddies from the WI, isn’t it?” she thundered.

Henry sheepishly agreed. But before she went off on one and wrecked both their evenings, Henry stated that he always stuck up for Connie against any slight they threw.

“What slights? There are other slights? Oh, this gets worse,” Connie said.

“You know how they are,” Henry stammered. “All set in their ways.”

“The way they carry on, you’d think I turned up to evensong in me knickers,” Connie said. Despite her tough exterior, she was hurt by what people thought of her. She was especially hurt by what Henry thought of her. It was as if the naysayers didn’t think she’d stick at her marriage were convinced she’d break Henry’s heart. She was sure that some of them were keeping a tally of how many days they’d been married, waiting in anticipation for the break-up. And she knew he’d secretly like her to get on with it and behave as he thought a vicar’s wife should.

The fact was that small-minded people would always judge her.

“If you turn up to evensong in your knickers, even I’d find that hard to defend.” He smiled. “But I’d appreciate the view.” He was making an effort again, even though he’d run a million miles if she actually did it.

Connie looked at the newspaper article on the table.

She thought of the finger-pointers reading it and judging – and she decided that she didn’t want to see it anymore. Henry agreed to keep it out of sight but he’d put it in a scrapbook. He was proud of his wife. He knew they’d look back on it with pride in their later years. This comment gave Connie heart. He saw this as a long-term commitment. He was willing to work at it.

In Finch’s kitchen, Connie mopped up the last of her soup with her bread. Joyce eyed Finch, who was draining the dregs of his bowl directly into his mouth. “Are you helping us this afternoon?”

Finch looked sheepish. He wiped his mouth with the back of his sleeve.

“Tea towel,” Esther snapped.

But Finch ignored her. He shook his head at Joyce’s question, tapped his nose and chuckled. “No, I’ve got a more pressing appointment, heh.”

Joyce looked at Esther for an explanation. But Esther shrugged.

“Search me. I don’t keep his diary. And I know it’s best not to ask.”

Connie glanced at the clock and mentally started to count down the hours until she could return to her home and her husband. Even though there was a war on, and even though she and Henry had frequent arguments, Connie felt the happiest she had ever felt.

As soon as the school bell rang, Margaret Sawyer burst out of school with an unusual keenness to get home. She barely had time to shout goodbyes to her friends as she legged it over the playground and out of the gate. Running past the village square, Margaret dodged a couple of GIs, who were making their way along the street. She ran past Mr Jeffries’ sweet shop, a place where she usually liked to dawdle looking at the tasty confections in the window and imagining her perfect selection, and down the hill past a row of terraced houses. Then she was off over a field of long grass and down a ravine by a small stream, after several miles coming to a small thatched cottage amid a cluster of fields like a single flower sewn onto an eiderdown. This was home. Jessop’s Cottage, although Margaret wished she was back at her proper home in the East End of London. But she knew she couldn’t go back. Her real mum was dead.

The cottage was a place remote enough from the village that no one came here. And that was how Michael and Vera Sawyer liked it. He would often rail against the conspiracies that he saw in every shadow; the untrustworthiness of human behaviour. Margaret let these rants pass over her head, failing to understand how he could get so riled over things that were probably the inventions of his mind. No one was out to get them. No one wanted to take their lives here away from them. And while Michael stayed in the cottage or worked the garden, Vera would make necessary trips to Helmstead but try not to get drawn into conversations with anybody. They lived like ghosts and Margaret supposed that was just the way they liked things: the three of them, insular and alone.

She flung open the door and heard Vera’s voice call out.

“Margaret? Is that you?” She was clearly surprised that the girl was back so soon. Margaret said hello and put her school bag and coat neatly on a hook in the cupboard under the stairs. The place. She glimpsed the small wooden step that she would sit on for hours on end. Luckily, on this occasion, she closed the door on that sad and lonely part of her world. Maybe she’d be sent there later, but not yet.

The stern-looking woman from the train crash came through to the living room, wiping her hands on her apron. Vera looked the young girl up and down, suspicion in her eyes. Why had she rushed back?

“They let us out early,” Margaret lied, trying to control her panting from the exertion of running all the way.

Vera seemed to accept this statement.

“Wash your hands, then there’s some darning to do.” Vera returned to the kitchen. With her out the way, Margaret had a scant few minutes to do what she intended to do when she’d left school so quickly. She looked at the small collection of letters on the sideboard. Underneath was a copy of The Helmstead Herald, unread and still folded neatly. Margaret tucked it under her jumper and ran to her room. Once inside, she quietly closed the door, hoping Vera wouldn’t hear her latch and realise where she was. She pulled the newspaper from under her jumper and opened it out. Skimming through to page five, she found the thing she was looking for. Connie Carter in the photograph. Margaret pulled out the sheet of newspaper. She knew not to tear it as it would leave a single page on the other side of the middle of the newspaper, so she removed all four pages. She closed up the edited edition; worried that it felt thin in her hands. She had no choice but to trust that Michael wouldn’t notice that four pages were missing when he read it. She tucked it back under her jumper and quickly folded up the excised pages and put them safely under her bed. But as Margaret turned to go back down to the living room, she realised Vera Sawyer was standing in the doorway.

“What are you up to?” Vera could read the guilt on the young girl’s face.

“I just wanted to change,” Margaret stammered.

Vera shook her head. “I’m not doing more washing. You wear your uniform for now. Come on.” She pulled Margaret by the hand, downstairs to the living room. All the while, Margaret hoped that The Helmstead Herald wouldn’t fall from her jumper. Luckily she made it to the dining table, where seven pairs of holed socks were waiting for her. Vera scowled and went to the kitchen demanding that the darning was finished by teatime. Margaret turned silently in her chair, placed the newspaper back where she had found it, and went to work on the socks. Phew, she’d done it.

Later, after tea, Margaret washed up the plates with one eye on the living room, where Michael sat reading the paper. He was dressed in his shirt and tie – an outfit in which he would inexplicably work in the garden. Standards had to be maintained, as he often said. Margaret hadn’t thought much about it, but occasionally she would wonder how Michael made any money. She knew he sold, or rather Vera sold, vegetables grown on his large plot. It didn’t seem to make much money, but enough for the family to get by. For now, Margaret was more concerned with The Helmstead Herald. Would Michael feel it was thin and realise a spread was missing? Or would he give the paper a cursory glance and then go back to his shed?

Finally, he closed the newspaper.

“Not much in it,” he sighed, reaching for his tobacco.

“Nothing much happens around here.” Vera shrugged as she knitted a brown scarf by the fire. “We should be grateful really.”

“Surprising they didn’t report on the train crash,” Michael commented.

“They did,” Vera said.

Margaret’s blood ran cold. Had Vera already read the paper? Surely not – as she’d have kicked up a storm if she’d seen the picture.

“They did a front page on it last week. There was a picture of the train wreck and everything.” She wanted to move on to another subject, wary that Michael would blow up again about them taking the train and risking their lives.

Michael knew about the front-page story, but just wondered why they hadn’t done more on it, that’s all. Like most people, he knew that they usually follow things up with a report centring on the human-interest stories around the main event. It was a good opportunity for the local rag to fill its pages with stories that might actually interest people for once.

“Maybe they will when they find out who did it,” Vera said, missing a stitch.

“Who knows if they can ever catch these people.” Michael rose from his chair.

Margaret dried the last of the plates and brought them through to the Welsh dresser. Carefully she opened the door and placed the china inside, aware that Vera would always watch her like a hawk to check she didn’t chip anything. Relieved that all the plates were in place, undamaged, she asked if they needed anything else doing.

Vera shook her head. Margaret could go to her room and read her books if she liked. The young girl went off. She liked it when she was in her room with her own thoughts. Upstairs, Margaret opened her copy of Black Beauty by Anna Sewell and read a few pages. She listened as Michael moved to the front door and went outside to the shed.

With Michael gone, Margaret knew that Vera would come up to check on her soon, so she ensured that she was reading studiously when she entered. Vera asked if she wanted a glass of milk. Margaret declined politely. Vera left and as Margaret heard her footfalls retreating, she pulled out the pages of The Helmstead Herald from under her bed. She opened them up. A chance to study them at last. Margaret had heard from an excitable school friend that her picture was in the newspaper and now she could see it for herself.

There was the picture of Connie Carter with Margaret. The story was a report on what had happened and what Connie had said to the reporter. Nothing that Margaret had said was in the piece. Nothing about where she lived. Margaret was relieved. She’d had a horror that in a daze of shock she might have said that Vera wasn’t her mother or something. But she still knew that if Vera even saw the photograph she would go mad. Any publicity would be hated by this private couple.

Margaret knew that she had to put it away. But she was mesmerised. She looked at the beautiful face of Connie Carter and thought about her kindness. The shared cheese, the offer of tea, the repeated enquiries about how she was. Connie had tried to find out if she was okay, even before the train crash. Connie Carter was even willing to stand up to Vera to ask that awkward question. Margaret’s heart swelled with warmth and pride at the heroine on the page. She liked Connie Carter. She wished she was her mum.

Frederick Finch couldn’t resist a good-natured chuckle at the sight before him. Henry Jameson dressed in a large pair of Wellington boots that were far too big for him, looking like deep-sea diving shoes. He was also wearing an oversized gilet, which sat on top of his clergy uniform: dog collar still visible for added comic effect. And on his head was a tweed flat cap.

“Do you not have a mirror in your house, Reverend?” Finch joked. This was Finch’s pressing appointment, the reason he couldn’t help the girls in the fields. He was teaching Henry the fine art of hunting.

“If we could just get on, Mr Finch,” Henry replied. “I’ve got a christening in an hour and a half.” He didn’t see what was so funny in his appearance and he felt that Finch’s laughter was further emasculating him after Connie’s mockery. He just wanted to catch a rabbit and prove Connie wrong. That would show her once and for all.

“Now, where are the guns?” Henry asked, keen to move things along.

“Guns? You don’t need a gun to catch a rabbit.”

“Don’t you?”

“Well, you could, but it wouldn’t leave much of it for your pot,” Finch explained. “No, we use traps for those little fellas. Here’s your weapon.”

And Finch delved into the pocket of his ample cardigan and produced a ball of twine. He placed it in the soft hands of Henry Jameson.

“String?” Henry asked in confusion.

Finch tapped his nose in a you’ll-see kind of way. Then he rubbed the back of his neck – mild concern filtering into his chubby features.

“You might have to delay that christening,” he said. “Can’t see how we’re going to do all this in an hour and a half. I bet it’ll take that long for you to learn the knot.”

“This is the first lesson. That’s all,” Henry said, regaining his enthusiasm. “As long as I can catch my own rabbit, eventually, and prove Connie wrong, I don’t care how long it takes.”

Finch exhaled. “All right. First thing is to tie a slip knot on the end of that twine.”

“A slip knot?” Henry hesitated.

“Let me show you,” Finch said, taking the ball of twine. This was going to take a long time.

A big blue bottle flitted annoyingly around Connie’s nose. She batted it away with a muddy hand. Connie and Joyce were digging manure. It was one of their least-favourite jobs – but at least they were back on Pasture Farm. Their secondment had come to an abrupt end after the train crash. The track needed repairs and it would take over a week to fix them. And without the track, there was no way to get to Brinford Farm, other than in Finch’s tractor and trailer. But he didn’t have sufficient petrol rations to take the girls every day and bring them back. So the arrangement was curtailed. The girls were back on the farm they loved. It was just a shame that a tragedy had had to occur for that to happen.

Connie eyed Dolores O’Malley with annoyance. The older woman was resting on the handle of her shovel. Her third break in ten minutes. If she stopped any more often she’d start to develop roots.

“Come on, Lore, pull your weight,” Connie said.

“I’m finding it’s hurting my back,” Dolores admitted.

“You need to get your shoulder behind it,” Joyce offered. “Then it won’t hurt your back. Lift from the knees.”

“Really? How do you know all that?”

“Painful experience,” Connie replied. “We’ve shovelled more sh-”

“She’s right,” Joyce chipped in.

Dolores reluctantly put her shovel back into use, cutting through the rich manure and transferring a load to the cart nearby. She was a prickly woman, hard to engage in conversation and quite shut off from opening herself and her feelings up. It wasn’t that she judged the other women, just that she had no real desire to interact with them. This seemed odd. A strange way in which to make the time fly by at Pasture Farm. Joyce thought that this would make her war a lonely experience, so she and Connie had taken bets about who could get Dolores to open up the most. They’d both repeatedly tried different gambits, from Connie trying to find out her favourite dessert to Joyce talking about her husband in the hope that Dolores would share something of her private life. As it was they didn’t know what her favourite dessert was (“I don’t mind really”) and they didn’t know whether she was married or not (“It’s nice that your John has left the RAF and is out of danger”). She was a very private person. The facts they did know were scant: Dolores had arrived on Pasture Farm a month ago from Reigate in Surrey (although she was from Dublin originally). Before being conscripted as a Land Girl she’d been working at the American airbase at Redhill as a nurse. And it was her experience as a nurse that was why she ended up at Helmstead as the Land Girls often had to take shifts at the military hospital at Hoxley Manor on the estate. Dolores’s experience meant that she was given the position of ward sister when she did a shift there. It also meant that Connie and Joyce would have to take orders from her at Hoxley Manor: something that Connie, in particular, resented as Dolores would become very judgemental. She knew best when it came to nursing and she wasn’t afraid to show it.

As they dug the manure, Connie winked at Joyce. To pass the time, she was going to try another gambit to find out more about Dolores.

“What’s your favourite colour, Joyce?” Connie asked.

Joyce saw where this was going and replied, “Yellow is nice.”

“Dolores?” Connie asked. Surely this couldn’t fail? Something as innocuous as a colour. But it wasn’t to be.

“I don’t know really. They’re all nice.”

“But you must have a favourite.”

“Not really. I haven’t thought about it.”

“Well what colour’s your bedroom back home, then?”

Joyce could hardly contain her smile at how Connie had managed to get the conversation onto something quite personal from such unpromising beginnings. But maybe Dolores noticed the smile, because she clammed up even more than usual, portcullis defences coming down.

“What a strange question,” Dolores muttered, continuing with her digging. “Why are there so many roots down here?”

Connie looked at Joyce and the two women shared a small shrug. Good try, Connie, but that one didn’t work either.

“That’s another penny you owe me,” Joyce whispered, returning to work.

“I’m going to be broke at this rate,” Connie grumbled.

Henry checked his watch. He had fifteen minutes before he was due in church for the christening. He calculated he could stay here for another five minutes before he had to rush back to the vicarage to prepare everything. It was annoying that Connie wasn’t at the vicarage to put things in order. But he knew she had her duties as a Land Girl. However, there was a nagging feeling that even if that work didn’t exist, would she be there helping him? He put the thought out of his head and stared at the trap.

He had just five more minutes to catch a rabbit. It had taken him ages to tie the knot. As fumbled attempt built on fumbled attempt, Finch had waited with glee for the vicar to let loose with a swear word. But like Connie and Joyce waiting for Dolores to say something personal, he’d been disappointed. Henry had kept his cool and eventually managed to tie it.

Now, he was lying in some heather in a wooded area of the farm. Finch was beside him. Henry was holding one end of the twine; the other was fashioned into a loop twenty feet away near a tree. Henry was waiting for a rabbit to hop over and put its foot in the loop. Then he’d pull his end, closing the loop and trapping the rabbit.

“Isn’t there an easier way?” Henry whispered.

“All good things take time,” Finch offered, sagely.

“You didn’t think that when you made that carrot whisky. It was horrible,” Henry retorted.

“I had overwhelming supply demands so I had to rush that. This is different. Nature has its own pace.”

“But we haven’t seen a single rabbit.”

“Maybe it’s because you keep talking, Reverend.”

“I don’t keep talking.”

“Well, what are you doing now, then, eh?” Finch chuckled.

Henry shook his head. He was cold and the front of his body felt decidedly damp from lying in the heather for so long. He knew he wasn’t going to catch a rabbit today.

That evening, Connie walked back to the vicarage. As usual, her muscles were aching and she had blisters on her hands. She was looking forward to supper with Henry and an early night. And hoping that they could just have a nice time. But then she remembered that Henry would be late back. He was visiting an elderly French man who lived in a cottage on the edges of the Gorley Woods. Dr Beauchamp was dying and liked Henry to visit him to give him strength and comfort during his final days. And the conscientious young vicar felt obliged, even happy, to do his duty. Connie knew that Dr Beauchamp liked to talk, at as much length as his breathing problems would allow, about how his country was now occupied by the Germans and about how proud he was of his own son, who was fighting for the resistance there. So Henry wouldn’t be back until late.

Connie resigned herself to the mixed emotions of facing an evening alone. There would be no more disagreements or friction, but she’d miss him. As she approached the porch, she was surprised to find a visitor waiting on the doorstep of the vicarage. It was Roger Curran, the reporter from The Helmstead Herald. He tipped the small trilby on his head at her. Connie wasn’t sure if it really was a small hat or that it just looked small on his large head. He smiled warmly at her.

“Mrs Jameson! I have the most splendid news.”

“Oh yeah? What’s that, then?”

“Do you know? I’ve often heard that vicar’s wives make the very best tea.”

“I wouldn’t bank on it,” Connie said under her breath. But with nothing more pressing to do, she invited the journalist inside, slopped water into the kettle and put it on the stove.

The two of them were soon sitting around the dining table and Roger Curran’s podgy fingers were taking a second biscuit from the plate Connie had provided. He sipped at his tea and winced slightly. Connie knew it wasn’t one of her best efforts, but she found making tea really unaccountably tricky. She had made Roger Curran a ‘milky horror’ (as she liked to call it), with too much milk and too little tea. She guessed that he might revise his patter about vicar’s wives making the best tea from now on as he sipped it with a grimace.

“I’ll come straight to the point, Mrs Jameson,” he said, wiping a crumb from his lips. “It seems my little story has been picked up by one of the national newspapers.”

Connie looked surprised. She wasn’t sure whether she felt happy about that. “Well, can’t you stop them?”

Roger smiled. “Oh no, it’s a good thing. It means I get credit for a story that many more people will read. And that means a lot more people will know about your heroism. And I hope I’m not talking out of turn when I say that although the story is just the sort of inspiring thing that Blitz-torn London needs to read, its success is also due to how fine you look in the photograph, Mrs Jameson.”

Connie felt uneasy at the attention. Henry wouldn’t be happy about her being seen as some sort of poster girl for plucky Britain. The wolf-whistles outside the pub were enough to get Henry’s back up, without any added spotlight. She put it out of her mind and asked about the explosion. Had the police found out who was responsible yet?

Roger shook his head, spraying crumbs like a Labrador shaking itself from a bath. “They’re not sure. But the remains of the device were the same as one used to blow up a post-office truck a month ago. And the station guard at Brinford recalled a tall man taking the train, the same one you got, every day for the seven days before the crash. He wasn’t on it on that fateful day, but people are saying that his other journeys were for reconnaissance. Check the timings and that.”

It chilled Connie that a seemingly ordinary commuter, a man who would go unnoticed in the daily bustle, could have been there timing the journey to the precise second.

After another biscuit, Roger Curran tipped his small hat a second time and left the vicarage (his tea largely untouched). The story would be in a national newspaper! Connie shrugged. She hoped it would still be tomorrow’s fish-and-chip paper and then it would all be forgotten about. But she would be wrong. It was a story that would change her life.

Margaret Sawyer froze in fear as she approached her house. Roger Curran, the reporter from The Helmstead Herald was standing outside the front door. He’d come to the house. No one ever came to the house!

He rapped on the knocker, brushed the biscuit crumbs from his tank top and cleared his throat. He glanced nonchalantly at the neat front garden, decorative rows of small box bushes trimmed into squares alternating with rhododendron bushes that were showing their last flowering for the season. The whole design was so regimented that Roger Curran assumed a soldier must live here.

Margaret ducked down behind a wall, peering over the top to see if Vera or Michael would answer. She prayed that neither of them were inside the house. Vera might be out selling vegetables and Michael was probably in one of the outbuildings, tending to his seedlings. And even if Michael was at home, he rarely answered the door, so she thought she might be safe on that score.

After what seemed like an age, Roger Curran turned on his heel. He glanced up at the house one last time and made his way down the path. He passed the low wall where Margaret was hiding, but didn’t see her. She was relieved. So much for eagle-eyed journalists!

As she watched the rotund figure amble away down the lane, Margaret hoped with all her heart that he wouldn’t return and that would be an end to it.