Читать книгу The West African Manilla Currency - Rolf Denk - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Classification as manilla or Manille happens for a large variety of different types of West and Central African metal rings. “True” manillas in West Africa represented a real means of payment for about 500 years. This was both in trade between Africans and Europeans and between the Africans themselves. Consistent use of the term “manilla” makes one think that all possible forms of metal rings in West Africa had a means of payment function.

Deutsch (1957:124) wrote:

Leider wird nun aus dem Schrifttum so recht nicht einmal klar, welche Form von Ringen mit dem Ausdruck Manilla bezeichnet werden soll. Es scheint, daß zuweilen alle ringförmigen Metallstücke so genannt worden sind, sicherlich eine unzulässige Ausdehnung des Begriffs.

Obwohl nun diese Manillas im Schrifttum häufig erwähnt und [manchmal] abgebildet sind […] ist im Grunde doch erstaunlich wenig darüber bekannt. Eine Monographie liegt noch nicht vor. –

Unfortunately, it is not even quite clear from the literature which form of rings should be termed manilla. It seems that sometimes all ring-shaped metal pieces have been so termed, certainly an unacceptable extension of the term.

Although these manillas are frequently mentioned and [sometimes] depicted in the literature, […] surprisingly little is known about them. A monograph is not yet available.

To avoid further misinterpretation, knowledge currently available in existing literature will be presented in the following chapters. The aim is to determine the type of manilla and to collect data on their places of production, regions of use, type of application, size, weight and metal composition. Unfortunately, all information is only available for an object or a group of objects in very few cases. There are unusually large gaps in the metal analyses, although some essential findings can be gleaned from them.

Six explanations are offered for the term manilla’s1 emergence:

1) According to “Michaelis Concise Dictionary Portuguese-English” manilha is translated as bracelet, armlet, shackle, fetter, manacle.

2) Portuguese diminutive of the Latin word manus = hand: manilha

3) Composition of the Portuguese words mao = hand and anel or anilho = ring (Roth 1903:5 n3)

4) Transformation of the Latin word monile = collar (plural: monilia); Portuguese manellio (Grey 1951)

5) “Originairement on appelait manilles les cercles de fer mis aux poignets et aux chevilles des esclaves […]” (Vacquier 1986:233) – “Originally, the iron rings around the wrists and ankles of the slaves were called manillas […]”

6) According to Betham (1837:94; 1836:21), the word manilla has a Celtophoenician origin. Literally it would mean the value or representation of property. Main = value, and aillech = cattle or any form of property.2

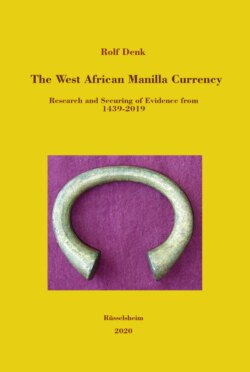

A manilla is a metal object used in trade and payment transactions with West Africa. It is primarily understood to be an open ring made of copper or an alloy of copper, lead, zinc or tin, used explicitly in the Kingdoms of Congo and Benin. It was produced in Europe specifically for Portuguese trade with West Africa. It is not intended as a jewellery ring, and its opening is too large to be worn on the arm.

The later French and English manillas are too narrow for use as bracelets. Although the shape of [Birmingham] manillas reminded to a former ornamental use, […] a manilla in the 19th century looked like a finger ring [?] and had no other function than being a means of exchange. (Müller, B. 1985:62).

Hawkins (1958:344 n1) defines:

Manillas are small metal objects in the shape of a horseshoe. They were extensively used as a currency in Southern Nigeria and had no other function.

However, they differ significantly in weight, shape and metal composition from the original Portuguese manillas.

In 1975, Jordan wrote:

[…] verstehe ich darunter [gemeint sind Manillen] jede von einem ringförmig verbogenen Metallstab ableitbare Struktur mit oder ohne Schluss, deren Verwendung als Zahlungsmittel nachzuweisen ist. –

[…] I mean by it [meaning manilla] any structure that can be derived from a ring-shaped bent metal rod, with or without a closing, the use of which as a means of payment can be proven.

This definition was too broad. Even if one takes into account that the restriction was made, when use as a means of payment had to be proven. Such unequivocal proof is only very rarely possible for one of the numerous indigenous ring forms. In 1957 Deutsch had already called such a broad interpretation an “impermissible extension of the manilla concept”. (Deutsch 1957:124).

Snodgrass (2003:278) even classifies locally produced metal necklaces from Ghana and Nigeria as manillas. She writes, “The wearing of a manilla produced an overt boast of wealth, especially when placed around the neck.” But undoubtfully manillas never have been a neckornament.

Foot and neck rings are not manillas. Indigenous bracelets are also not manillas. Even the so-called king, queen, snake or coiled and knot manillas are strictly non-currency manillas, in both their form and their provenance. However, they are other metal objects for which a clear designation is still missing (see also Chapter 18). The assertion that one could have bought up to one hundred slaves with a “king manilla”3 is not true and lacks evidence. Also, that once king manillas and (Birmingham) manillas had a value relationship in the ratio 1 to 1004, has so far remained unproven. The latter statement could be based on a note about a queen manilla in the Liverpool County Museum5, which states that this queen manilla was used in Nigeria as money and corresponded to a value of 100 (Birmingham) manillas.

Queen manilla, Nigeria, Copper, formerly used as currency; said to have been worth 100 manillas. Made twice-twisted copper rod in shape of elongated penannular ring. (Rivallain 1987:454 n1).6

In early written records such as trade lists, price lists, or travel reports, one often reads only of metal rings (copper, brass or iron rings), sometimes also only bracelets, so that a manilla classification can only be made according to the accompanying circumstances.

The following pictures (Figs. 1a, 1b) from the publication by Okwara O. Amogu (1952) show that the local population misinterpret or at least imprecisely interpret the term manilla.

When working on the manilla theme, the further one goes back in time, the more difficult the source situation becomes. This is due to the fact that only a few people were interested in this rather insignificant question and that manilla users only occasionally paid attention to them. For manilla users, these were everyday objects that did not require any particular description. On the other hand, the earliest references to manillas can be found in ancient Portuguese documents, which are only accessible to a few, due to most being unable to read the language – the root of the word manilla derives from the Portuguese word manilha.

Sources, if any are available, have so far only been consulted by individual non-Portuguese people, and then only worked on under for other reasons than for clarification of manilla appearance, origin and use.

If the circumstances above apply, then one can only resort to text translation into English, French or German. whereby one must keep in mind that misinterpretations can also occur from the translation of Old Portuguese at least in the case of the secondary theme of manilla.

1 All bold highlights in the text and also in the citations are from the author.

2 See also Einzig 1966:241; Davies 2002:46–47.

3 Brooks 1971: Text to his Fig. 4.

4 Quiggin (1949/1963:90); Sigler (1953:142); Clain-Stefanelli (1979:6).

5 Today's name of the museum is not known.

6 Not sure if it refers to a king or queen manilla due to the given description.