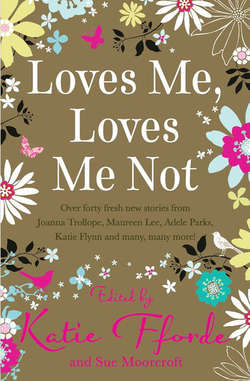

Читать книгу Loves Me, Loves Me Not - Romantic Association Novelist's - Страница 8

Rembrandt at Twenty-Two

ОглавлениеI promise you, I saw him from the stage. I couldn’t miss him, not the way he was looking at me. I was up there, front row, final chorus, stockings and suspenders, and he was out there, in the stalls, centre, only two rows back. Our eyes met. Well, not just met. Our gazes kind of fused. I’d never known anything like it, and there isn’t a name for it, that kind of attraction, and perhaps there shouldn’t be, because it’s different every time, different for everyone.

Well, of course, he was waiting at the stage door.

He said, ‘Hello, gorgeous.’

I said, ‘You foreign?’

He smiled. He had a fantastic smile. He said, ‘I’m Dutch.’

I said, rudely, because I was so wildly excited, ‘You can’t be. Dutch boys aren’t tall, dark and handsome. Dutch boys are blond and look like potatoes.’

He laughed. Then he kissed me. Can you imagine being kissed by a total stranger and wanting him never to stop? And then we went for drinks, somewhere hot and dark and noisy, and then he said he’d got to go.

‘Go?’

‘To catch a plane.’

‘Where?’

‘Home. Back to Amsterdam.’

‘You can’t, you can’t—’

‘Come, too.’

‘I can’t. I’ve got a show to do—’

‘Come tomorrow.’

‘I can’t—’

‘Come.’

I looked at him. He looked back, like he was looking right into me, like he knew me. Then he picked up a paper serviette and wrote something on it.

‘Meet me there. Sunday. Three p.m.’

I peered at his scribble. ‘Can’t read it—’

‘Meet me,’ he said, ‘in front of my favourite painting. In the Rijksmuseum. Three o’clock Sunday.’

‘I’ve never been to Amsterdam—’

‘It’s easy,’ he said. ‘Everyone speaks English.’ He leaned forward and kissed me. ‘See you there, gorgeous.’

I said, ‘Can I have your number?’

He took my hands. He said, ‘No need. This is special. This is something else. This is a beginning.’

Of course, I went. I danced myself to a standstill in the Saturday matinee and the evening show, and when I came off stage, Sam, the stage manager, who could do praise as well as he could fly, said, ‘Nice work,’ looking straight at me. And then I went out of the theatre without a word to anyone and got a night bus to Stansted Airport and the first flight out to Amsterdam. I was so high on the thought of seeing him that you could have powered a city off me. Two, maybe.

That energy carried me through the night, through the next morning. It was like surfing a big wave that never quite got to shore. I bought coffee, I bought apple cake, I went brazenly into a big hotel and used the ladies’ room to wash and do my make-up and my hair. I talked to people and he was right, they spoke English, and they smiled, and they talked back to me. And at a quarter to three I was where he told me to be, in this huge old museum, crammed with visitors, standing in front of a painting of a boy with a big mop of frizzy hair and a face like a potato. Zelfportret ca. 1628, it said underneath. Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn at twenty-two. I stared at him. He looked back out of his painting, over my shoulder as if he was waiting for someone.

He had a long wait. No one came. I waited two hours, and my Dutchman never came. I went out and drank gin, which there seems to be a lot of in Amsterdam, and got myself a weird hotel room near the station, and drank and cried and drank and cried until I fell asleep.

I went back the next day, in case he’d said Monday, not Sunday. And then I went back on Tuesday and Wednesday and Thursday. And, on Friday, something clicked in my brain, and I actually registered the messages on my phone, and a different sick fear slid down into my stomach. The fear of being let down was added to by the fear of losing my job.

‘Where the hell are you?’ Sam kept saying. He sounded furious. And then, ‘There are plenty more where you came from. Plenty.’

I don’t really want to talk about that journey home. You can imagine how I felt—we’ve all been there. We haven’t all been as stupid as to go all the way to Amsterdam to get there but we’ve all done the dumped, humiliated, disappointed, how-do-I-go-on thing. I looked at myself in my compact mirror as I sat on the bus from Stansted to London and I thought that nobody would ever fancy me again, and that if I were them I wouldn’t fancy me, either.

I got to the theatre early, about four-thirty, three hours to curtain up and nobody much in yet but the technicians. I went into the big dressing room that all us girls in the chorus shared and to my relief there was no one in there except Monica, who’d been cleaning up and calming down in that dressing room for about a hundred years. We called her Mon and sometimes, when we were tired or upset because we’d fluffed a move or got kicked on stage, we called her Mum by mistake and she never minded.

She was sweeping the floor. Clots of cotton wool and chocolate wrappers and hairballs. She stopped sweeping when I came in.

‘Where’ve you been?’

I slumped in a chair and looked at myself in a mirror with all those light bulbs round it. I said, ‘Amsterdam.’

She leaned her broom against the wall. ‘What for?’

I fished around in my bag and pulled out a postcard. I put it down in front of me. ‘To look at him.’

She came over. She smelled, as she always did, of fags and carnation soap. ‘And?’

‘It’s Rembrandt. When he was twenty-two.’

Monica said, ‘I know about Rembrandt.’

I said, ‘I’ve screwed up. I haven’t got a love life and I’ve lost my job.’

Monica looked at the postcard. ‘Twenty-two. How old are you?’

‘Twenty-three.’

She sucked her teeth.

I put my head down on my arms, on Rembrandt. I said, ‘What am I going to do?’

‘When he painted that painting,’ Monica said, ‘he didn’t know his future. Did he? He didn’t know he was going to be the greatest. He just knew he could paint. That he’d got to paint.’

‘I can’t paint,’ I said, into my arms.

‘You can dance,’ Monica said. ‘You can dance better than most of them. You can sing.’

‘Sam won’t let me. Not any more.’

‘You know,’ Monica said, ‘about Samuel Beckett?’

I lifted my head. My eyes and nose were red. ‘I’ve heard of him.’

‘He said, “You try, you fail, you try again, you fail better.” You’ve got to try. You’ve got a future to make. You’ve got to try.’

I sniffed.

‘Get up,’ she said. ‘Get up and get moving. Wash your face. Find Sam.’

Sam was on stage, with the techies. They were fixing something to do with the steps we had to come down, high kicking and singing. There were places where they didn’t feel too solid, those steps, and we used to shove each other about to avoid those places. I went and stood beside Sam. He had a clipboard. He didn’t look at me.

‘Push off,’ Sam said.

I didn’t say anything. I didn’t move.

‘You heard me,’ Sam said.

‘I’m sorry—’

‘Too late,’ Sam said. ‘I’ve replaced you.’

I said, ‘I’m back.’

‘Without your Dutchman.’

I said, ‘They look like potatoes.’

He wrote something on his clipboard. Then he said, ‘At least I don’t look like a potato.’

I looked at him. He didn’t. He looked fine.

Sam shouted something at the techies. Then he said, ‘Go and get me a coffee.’

I went on looking at him. I said, ‘How d’you know about the Dutchman?’

‘I make it my business to know.’

‘About all of us?’

There was a beat.

‘No,’ Sam said.

‘I brought one back,’ I said. ‘A Dutchman. On a postcard. Rembrandt, when he was twenty-two. I don’t think I’ve ever looked at a man so long. I thought he looked like a potato but he doesn’t. He looks great.’

Sam shouted something else. He glanced at me. ‘I think I can cope with a postcard.’

I waited.

‘Go and get me a coffee,’ Sam said again.

‘Please.’

‘Please. Get two coffees.’

‘Two?’

He looked at me, red eyes, red nose, dirty hair. He said, very clearly, ‘Two coffees. One for you. One for me. Scoot.’

I felt my arms moving at my sides, like wings rising. Maybe I was going to hug him. He took a step away.

‘Scoot,’ he said.

‘But Sam—’

‘Scoot!’ he shouted, so all the techies could hear, and then he dropped his voice. ‘Don’t be long,’ he said. He smiled at me. He actually smiled. He had beautiful teeth. ‘Don’t be long.’