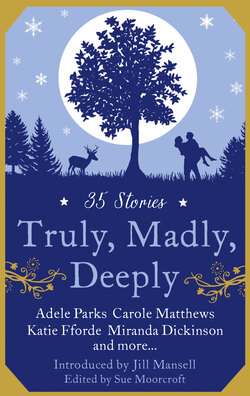

Читать книгу Truly, Madly, Deeply - Romantic Novelist's Association - Страница 35

True Love

ОглавлениеThe sun came out, flooding the room with brilliant light. Although his eyes were closed, the man turned restlessly on the bed and uttered a little moan. The sudden light had disturbed him. His wife rose and hurriedly pulled the curtains together, then returned to her chair beside the bed. She smoothed his brow.

‘There, there, darling,’ she murmured.

‘Where are we?’ he asked in a deep young voice that surprised her.

‘Why, at home, Robert,’ she replied. ‘On the farm. It’s morning, the sun’s just appeared, and two of your grandsons have already telephoned to ask how you are.’

His son, their only child, had enquired merely from a sense of duty. He’d been a strict, unforgiving father, not at all well-loved. But with his grandchildren he’d been openly fond and caring.

He was old, in his ninetieth year, and he was dying. Everybody knew that, his wife most of all. She’d loved him since they’d first met: she had been sixteen and he more than twice her age. Her father had been a parish councillor and he’d come to the house about a planning matter. He was a farmer; sternly handsome, smiling rarely. He’d proposed within six months and she’d accepted gladly.

‘I’ll make some tea,’ she said, not that he would understand. He’d heard nothing for days apart from internal voices he would occasionally converse with, voices that belonged to people she had never known. She left the dining room and went into the kitchen –he’d been brought downstairs and the dining room had been turned into a bedroom.

Through the window, the modern bungalow –built for their son when he took over the management of the farm –throbbed with life. Her great grandchildren, two little girls, were spending the summer there, and were already playing on a swing in the garden. Dorothy, her daughter-in-law, was hanging washing on the line and Francis, the ‘Crown Prince’ as Robert sometimes called him in a rare moment of humour, was staring at the house where he’d been born as if wondering how his father was today. At some time this morning, he’d come over and enquire about his health.

She was tempted to wave, but Francis would come immediately out of a sense of duty and she would sooner he didn’t. He would argue that his father should be in hospital.

‘He loathes hospitals,’ she would insist. ‘He’d far sooner be at home.’

She made tea and took two digestive biscuits out of the tin –she’d make herself a proper breakfast later –and took them into the dining room where, to her utter astonishment, her husband was singing an old war song.

‘There’ll be bluebirds over…’ he sang, followed by unrecognisable murmurings.

‘The white cliffs of Dover,’ his wife offered. Then she sang the line in full, ‘There’ll be bluebirds over, the white cliffs of Dover.’

She was even more astonished when he opened his eyes and smiled at her, a brilliant, open, truly gorgeous smile that was totally unfamiliar.

‘Hello,’ she said, taken aback, overwhelmed by the feeling of aching sadness that she would shortly lose him.

‘Hello,’ Robert MacEvoy exclaimed, almost exactly seventy years earlier. It was late September, the war was just over a year old –it had only been predicted to last six months. He’d just woken from his afternoon nap in the hospital of an RAF camp on the Essex coast and she was standing beside his bed with a cup of tea. She wore a blue and white uniform. A new nurse!

She laughed and put the tea on his bedside cabinet. ‘Hello,’ she cried, adding, ‘You’ve got a lovely smile.’

‘You’ve got a lovely everything.’ She was outstandingly pretty, with dark curly hair and eyes the colour of forget-me-nots. He was twenty-one and had never spoken so frankly to a girl before –flirtatiously almost. ‘What’s your name?’

‘Moira. Moira Graham.’ She made a face, squinting her eyes and wrinkling her nose. ‘What’s yours?’

‘Robert. People call me Rob.’

‘Well, I shall call you Robert, if you don’t mind.’

‘I don’t mind a bit. Will you be at the dance tonight?’ Another first for him; virtually asking a girl for a date.

‘I will indeed. Shall I save the last dance for you?’ She spoke in a deep sultry voice like Marlene Dietrich while fluttering her eyelashes.

He nodded. ‘As well as the first and all the dances in between.’

‘There’s just one thing, Robert,’ she said.

‘And what’s that, Moira?’

‘Have you forgotten you have a broken leg? It’s why you’re in hospital.’

He looked down at his feet protruding from under the blanket. The right one was heavily plastered, leaving only his toes bare. His ankle was also broken and his knee shattered.

‘I hadn’t forgotten, no. I thought we could sit the dances out. You can take me in my wheelchair.’

She looked serious for a change. Perhaps she felt the same as he did; that something remarkable and truly wonderful had occurred.

‘Oh, all right, so we’ll sit the dances out.’

The dance was being held in the canteen, the tables folded in a corner, piled on top of one another. He could limp a bit, his wheelchair was outside, and they were holding hands and sitting on one of the benches tucked against the walls. He was keeping his leg well out of the way, not so much bothered that someone would fall over it but that they would stand on his unprotected toes. The big room was crowded and the band played ear splittingly loudly.

‘What happened to you?’ she asked.

‘My plane crashed on landing,’ he said simply. ‘I was the rear gunner and thrown forward. Broke half a dozen bones. We’d taken a few hits over Berlin. It had needed a wing and a prayer to get us home.’

She shuddered and squeezed his hand. ‘Poor Robert,’ she whispered. ‘It must have been terribly painful.’

Robert shook his head. ‘I was knocked unconscious straightaway. I woke up in hospital, pleased to find I was alive and all in one piece. They sent me here to recuperate. Apparently, the hospital has a great reputation –it’s bound to improve with you there.’

‘I only recently passed my final exams. This is my first week as a nurse.’ She laid her head on his shoulder and began to croon ‘There’s A Boy Coming Home On Leave’ along with the band’s singer, a blonde in a tight red sequin dress.

Couples shuffled past locked in each other’s arms, even though they may have only met that night. There was a war on: Dunkirk was still painfully fresh in their memories, bombs were dropping all over Britain, Germany occupied several European countries, ships were being sunk. Life was cheap and thousands had already died. It meant that people lived for today and to hell with tomorrow.

It was hot in the canteen and his leg was itching madly. He wriggled uncomfortably.

‘What’s the matter?’ she asked.

‘I’d pay five quid to be able to scratch my leg,’ he groaned.

‘When’s the plaster due to come off?’

‘Another three weeks.’

She stiffened. ‘Will you be sent somewhere else?’

He shrugged, unsure. ‘I’m supposed to spend three months convalescing. Whether they’ll leave me here, I’ve no idea.’ He still suffered excruciating headaches.

His hand was squeezed again. ‘Let’s hope that they will.’

He’d been born in Kent when his mother was in her late forties and her other children had grown up and left. He’d been an unpleasant surprise and she had no love left for him. his father, a farmer, spent little time at home. Robert had sometimes wondered what life was for.

And now he knew. It was to meet Moira. She was meant for him and he for her. Both realised that after just a few magical, dreamlike days.

What good luck it had been that his plane had crashed when it had and with him as the only one seriously injured. He wouldn’t have wanted his good fortune to come as a result of a tragedy for others. He was in love, they were in love, and every day was a miracle.

‘Will you marry me?’ he asked when they’d known each other a fortnight.

‘Of course,’ she smiled back. ‘But do we really need a piece of paper to prove we love each other? We’re already married in spirit, if not in law.’

She was so familiar to him it was as if they’d known each other all their lives.

The day after the plaster was removed from his leg, they made love. For both it was the first time. Moira laughed a lot and cried a bit at their initial fumbling attempts to do it properly.

They chose the private ward of the hospital, the one with only two beds reserved for officers, empty now. The door was locked but they still worried. There were only three patients in the main ward: the other two were asleep. But Moira had been left in charge and if someone came and there was no sign of her, there’d be hell to pay. And if someone came and discovered what they were up to…!

‘We’d be shot at dawn,’ she said soberly.

‘Not before they’d pulled our fingernails out.’

‘Don’t joke, it’s not funny. We’ll have to find somewhere else.’

Night after night more bombs fell on more British cities. Sixty miles away London was being pounded ceaselessly. The war was spreading as the weather became colder and winter drew in.

As if in defiance of the misery being wrought upon them, the atmosphere in the camp became quite joyful. It was impossible to walk far without hearing a song being sung, a mouth organ being played, someone whistling. The dances got quite wild, but they finished with couples clinging to each other as if they never wanted to part. Groups of people would suddenly burst into song but likely end in tears as the lyrics touched hearts in a way the composer had never imagined. ‘Kiss the Boys Goodbye’, ‘We’ll Meet Again’, ‘Somewhere Over the Rainbow’: it was the language of love and loss, of words easier to say in song than spoken.

Robert was transferred from the hospital to a single room befitting his rank of Flight Sergeant. He needed a stick to get about so, for now, there was no mention of him being sent elsewhere. He was given a part-time job in the stores filling out order forms. Otherwise nobody bothered him.

When advised he could go home on leave, he replied he’d sooner stay on the premises.

‘Strange chap,’ commented the clerk who’d made the offer, eyeing him suspiciously.

Robert shrugged and said nothing. He just wanted to be with Moira. Nothing else mattered.

Three times a week, when Moira wasn’t working nights, they stayed in an old pub in Mersea, a watery village five miles from the camp. It was reached by a rambling bus usually full of RAF and Army personnel. Their attic room had a sloping ceiling, and was clean, comfortable and cheap. They were committed to sign in at the camp before eight o’clock next morning.

‘I don’t want us making love in a doorway,’ Moira said wrinkling her nose.

‘Or behind the canteen,’ said Robert. Some nights there’d be a whole row of couples.

Moira giggled. ‘Or in a lavatory!’

‘Oh, God, no.’

Other nights they sat in pubs or walked arm in arm on the flat sands where the moon was reflected over and over in the little pools that shimmered like diamonds, pausing to kiss and say, ‘I love you,’ for perhaps the hundredth or the thousandth time.

Sometimes, a German plane would fly over on its way back from London, occasionally dropping the odd bomb there hadn’t been time to release on its intended target.

They knew one day it would have to end. Robert’s health was improving, the headaches fading; he no longer needed a stick. They thought it unlikely both would still be there by Christmas.

‘What shall we do then?’ Moira asked.

‘Write to each other. See each other as often as we can –if we can.’ He could be sent abroad. So could she.

December came. Time was short. Each day began as if it was their last together. The weather worsened and it became icily cold. They spent as many nights as they could manage in the pub, making love full of wonder as well as sadness.

They were there one Saturday when the bar was crowded with military men and women, and locals. Songs, old and new, were sung, as well as Christmas carols.

Upstairs in their attic Robert and Moira made love. It was a surreal experience. The songs filtering up through the floorboards and sounding as if they were being sung in the room with them. As the night wore on, the music slowly faded until all that could be heard were faint voices, still singing, on their way to the bus stop.

They were lying in each other’s arms when they heard the plane approach. Moira got out of bed to watch it passing over.

‘Stay here,’ Robert implored. Had he sensed the danger he was to wonder afterwards?

She was at the window when the bomb plunged through the roof, taking away half the room, leaving him safely in bed on a shelf of severed floorboards. Robert watched, horrified, as she disappeared from sight amid tons of debris and a thunderous whooshing sound.

For a long time, it was like the end of everything.

Many years went by until the time came when he met a woman who loved him. They were married and she bore him a child. A day never passed when he didn’t think of Moira. Nor did a day come when he was as happy as he’d been with her: his one and only love.

And now, seventy years later, he knew they were about to meet again. He could see her more clearly than he’d ever done. She drifted in and out of his mind, she was foremost in his thoughts; singing, always singing. And now here she was, coming towards him, smiling, holding out her arms ready to embrace him.

‘I love you,’ he cried, opening his own arms to greet her. ‘Did I ever tell you how much I love you?’

The wife knew that he had gone. She wept, not just at his passing, but at the words he’d never said, not once, throughout their long married life. Still, it was wonderful to know that all that time he had really loved her.