Читать книгу No Room For Watermelons - Ron Fellowes - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

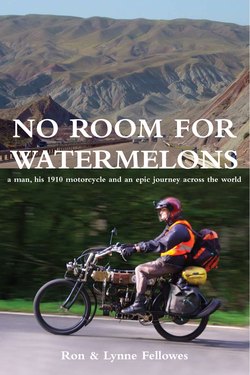

On Top of the World

ОглавлениеThe cold air packed a punch, and the heavy grey blanket hanging low over the world’s third-most polluted city threatened to swallow me whole. It might have been kinder to my lungs to stay on the plane.

Before going to find the FN, I searched for a phone-card seller.

‘I need to have your photo for our records,’ he said, yet barely glanced at my faded passport shot. It fazed him not at all that I was now grey-haired and a score years older. A photo of the flying nun would have satisfied him.

The clerk at Thai Airlines did the paperwork on a ‘Hemingway’ typewriter — an ideal contraption considering Nepal’s sporadic power supply. No money changed hands, either for the bill of lading or the carnet. Soon I was cheerfully on my way. All so easy!

Even though the customs shed was only a short walk away, a pushy tout insisted that for $20 we could drive there in his friend’s taxi. I refused. He stuck to me until we reached the shed, where he made one last attempt to get paid just for accompanying me. I sensed challenging times ahead.

Despite repeated checks at the counter, for two hours customs officials shuffled paperwork. Two men took me aside, and, out of earshot of the counter staff, told me what it would cost to get my bike released. I guessed they were brokers, and that the real amount was much less.

It reminded me of how often this scenario is played out the world over. The game is to keep the sucker waiting for as long as possible. Then, when his resistance is low and he’s running out of time, hit him with a charge they think he’ll accept. Call it baksheesh, a bribe, an honest-to-god fee, whatever — it all adds up to the same. In Nepal, Cancun or Timbuktu, wherever, it’s money that makes the wheels go round. Nothing is ever free, no matter which god one prays to.

I glanced nervously at the time, then said I would leave the bike and collect it next morning.

‘No, no. Paperwork is cleared. Cannot store. You must take now.’

I argued that there wasn’t time to assemble the bike before the warehouse closed at five o’clock. He shrugged, went into his office, and closed the door.

The FN’s handlebars, controls and pedal gear had been removed in Brisbane to keep the crate as small as possible. Reassembling it, with every man and his yak getting in the way, wasn’t easy. Each took a turn at passing me tools I didn’t need; and each just had to check that the horn worked. My patience was being sorely tested. No sooner had I unbolted the metal crate than it vanished. The Nepalese know a bargain when they see one. No doubt the container would be sold for a tidy sum.

Caught up in the urgency of the moment and suffering the effects of high altitude, I was all fingers and thumbs. The gas tank had been emptied before the flight, so I needed fuel. All the fuel outlets in the city seemed to be waiting for a delivery. What now! One fellow finally relented and parted with two litres from his own bike — at an exorbitant price. But at least I could get on my way.

The FN started first time. After a short warm up, I was hustled out the door, still cramming luggage aboard as I went. I’d been told to show my paperwork at the exit checkpoint, but I wasn’t stopping. I played dumb, gave the security guard a wave, and rode on.

It quickly became apparent that I had brought far too much gear, but at this stage, I had no idea what to dump — or even which way to travel. I turned my pockets inside out trying to find where I’d written the address for the first night’s accommodation. The hotel was in Thamel somewhere. The signs, of course, were all in Nepalese. As luck would have it, there were two Thamels — and I was not going to make it to either before nightfall.

The bike stalled repeatedly because of water in the fuel. With traffic jostling around me, and horns blaring, I struggled to push the bike onto the footpath to drain the carburettor before I could re-enter the fray. At low speed, and with under-inflated tyres, the FN handled poorly under its excess load. And I wasn’t faring much better.

As twilight deepened, the risk of being on the road increased. I had once ridden after dark in Bolivia and almost run into a rope strung across the road. I swore I’d never be that dumb again. I stopped to weigh my options, my knees trembling. The mix of thin air and heady excitement were catching up with me.

‘Can I be of assistance, mister?’ a stranger asked.

I explained my problem.

‘It’s not safe to stop here after dark,’ he warned. ‘Better you come to my guesthouse. It’s not far.’

My head bobbed like a dashboard dog. I was grateful for the offer and too weary to argue. Together, we pushed the FN two kilometres before heaving it into the hotel foyer and pushing it out of sight.

The room was small, the shower cold and the bed hard, but at least everything was clean. I barely managed to charge my mobile phone before the hum of generators signalled the power had gone off. Exhausted, I switched off the light, lay on the narrow cot and closed my eyes. I’d just drifted off when there was a knock on the door.

‘Here, Mr Ron, something for you to eat,’ said the manager, grinning broadly. I thanked him for the packet of orange biscuits and crawled back into bed, appreciative of the gesture but desperate for sleep.

Immediately after breakfast, armed with two jerry cans, I went in search of petrol. I met an English-speaking taxi driver at a street corner, and for the next two hours we drove all over town, squeezing through narrow alleyways and knocking on door after door.

I’d ask, ‘Do you have any benzine for sale?’ and always, from chubby faces peering out beneath richly-patterned tasselled hats, came the reply, ‘Chaina’ (No). Householders in Nepal, I learned, squirrel away whatever petrol they can get their hands on, either for their own use or to sell on the black market. Today, no one was sharing.

Across the city, tangled webs of power lines link the buildings. Each morning, amid a constant cacophony, street cleaners sweep away yesterday’s odorous residue, while fruit vendors busily trade from their bicycles.

At every intersection, two-stroke bikes jockey for position. In an effort to reduce the smog the prime minister, Baburam Bhattarai, had ordered military personnel to use bicycles as transport at least one day a week. So pervasive was the pollution, it was hard to tell if his decree was making any difference.

‘Stay here,’ my friendly taxi driver ordered. ‘When they see you they don’t sell.’ Soon he came back from around a corner with six litres. In a way, he was probably right — except that we were now at a gas station! Although I paid twice the going rate, I was relieved I could at last get on my way. The delays were driving me nuts.

Back at the hotel, the bill for the night had my eyebrows raised. ‘I’m giving it to you cheaper because you’re old,’ declared the manager, pointing to the ledger’s list of names and prices paid. I thanked him and shook his hand. With hindsight, I should have checked the tariff first. Ah well, another lesson learned.

Before leaving Kathmandu, I needed to clarify the way to Pokhara. It was impossible to read maps on the iPhone, so I resorted to asking locals for directions. I figured I’d be right when two people pointed the same way.

Even with the luggage strapped on firmly, riding was difficult. Pedestrians and motorcycles darted in and out. I’d move a metre or two, then stop, move again, then stop … This didn’t sit well with the FN, and I hadn’t yet twigged the benefit of saving the clutch by turning off the engine and push-starting. I was about to learn the hard way.

Amid the mayhem — and with my nerves strung out — I felt the clutch slip. I pulled over to adjust it. That was when I discovered that the substitute fibre plates I was using were not up to the job. Wiping the sweat from my brow, I asked people gathering around if I could take the bike apart on the footpath. Everyone agreed, ‘Yes, yes, no problem.’

Of course, it was a problem for the owner of the shop in front of which I was doing my repairs. When he turned up, he basically told me to remove all the crap off his step and bugger off!

The parts were snatched up and spread on newspaper on the dusty road, no longer in any semblence of order. Thankfully, Yogendra and Hari, two local mechanics who had helped me remove the motor, took the clutch plates away. They ground them on a piece of concrete until the steel was clear of fibre. The FN normally uses 15 steel clutch plates, and I had replaced six of these with fibre plates to create a softer clutch. Fortunately, I carried the original steel plates with me as spares, so all was not lost. But I did break an engine mount in the process.

I was back on the road within three hours. The two young men who had helped refused payment and waved me on my way. For the rest of the day, I rode on extremely steep, potholed roads. One seriously precipitous section took half an hour to negotiate. I shuddered at the thought of riding in the opposite direction.

By now, the traffic was thinning. I passed two buses embracing each other after a head-on collision. I would soon become used to sights like this. Gripping the handlebars even more tightly, and trying to balance a spare fuel-can on the tank, I focused on keeping the bike upright.

As I rounded a bend on one sharp descent, the fuel can tottered and slid on to the road. By the time I had propped the bike against a post and scurried back, a car had run over the funnel of the plastic container, thus rendering it useless. Bugger!

Seventy-three kilometres from Kathmandu, I began searching for a place to spend the night. With great relief, I came across the Pokhara Guesthouse. Crowds of onlookers quickly gathered, eager to pose beside the FN and have their pictures taken with mobile phones. The name of the guesthouse proved a misnomer: I still had to travel nearly twice as far to get to Pokhara.

The English-speaking hosts were welcoming, and I was served a satisfying meal of chicken stew, rice and potatoes. It was just what I needed after such an exhausting day.

Ohading, a local schoolteacher, brought his class along to inspect the bike. Most of the children spoke English, and they were curious.

‘Where are you from?’

‘How old are you?’

‘Where are you going?’

‘How old is the bike?’

‘Where is your wife?’

I wondered how many times in the months ahead I’d be subjected to such interrogations.

When Lynne Skyped me that evening, and heard of the day’s hassles, she suggested I chalk it up as my initiation. She said that having survived the trials of the previous two days the rest of the journey would be a breeze. She knew I just needed to vent.

I told her the highway congestion was much like Bali’s, but then admitted that a conversation I’d had with a chap who’d ridden across the subcontinent had put the wind up me a little. ‘Nepal is a piece of cake,’ he’d boasted. ‘Wait until you reach India. It’s fucking insane.’

I decided, that if that were true, then I’d better stop complaining and enjoy the easy going while it lasted! Better to focus on tackling one day at a time — and remember to breathe deeply. There’s a level of comfort in going to bed believing tomorrow will be a better day, but things rarely turn out the way we expect.

Dark clouds gathered overnight, and when I set out for Pokhara early next morning, the storm hit with a vengeance. The FN started well initially, but when the motor became saturated it died. I tried rolling it downhill, but it refused to start again until I took shelter and dried the spark plugs and distributor. I don’t mind riding in rain, but this was over the top, especially with the electrics constantly dying on me.

My Huskie gear stood up to the elements for nearly four hours, which was remarkable considering the deluge. Eventually though, moisture began to seep through the seams, and my fancy waterproof boots also gave up the ghost. I refused to give in. Hunched down low over the tank, I was barely able to see a thing through the pissing rain.

The road had broken up so badly on one stretch that I could only travel at 15 kmh. I counted the wreckage of about a score of vehicles along the way. At 3.00 pm, after eight hours of torture, I crawled into Pokhara, chilled and bone weary.

Ten minutes under a scalding hot shower had me rejuvenated. From the hotel roof, I took in the view. For the first time, I began to appreciate my surroundings. The weather had cleared, revealing neatly cultivated valleys backed by majestic snow-capped ranges. It began to sink in: I was in the Himalayas, at the top of the world. Elated, I knew that life doesn’t get much more spectacular than this.