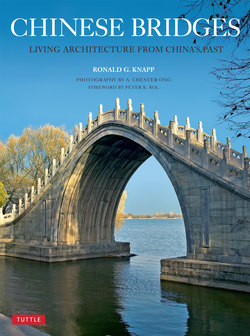

Читать книгу Chinese Bridges - Ronald G. Knapp - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеARCHITECTURE OVER WATER

Unlike palaces and temples—even houses—that are noticeable because of their façades and profiles, bridges, on the other hand, are frequently overlooked as architectural artifacts. Born of necessity to span streams, valleys, and gorges, bridges are literally underfoot and often inconspicuous. Yet, while sometimes merely utilitarian and unnoticed, many of China’s bridges are indeed dramatic, even majestic and daring architectural structures that epitomize the refined use of materials to span space. Joseph Needham, the great scholar of Chinese science and technology, asserted that China’s bridges combine “the rational with the romantic,” the workaday with the ethereal (1971: 4(3) 145). Unlike a building with walls and a roof wherein the structure is a means to an end, however, the structure of any bridge is as much a means as an end. In addition, a great many traditional Chinese bridges actually had buildings with walls and a roof built atop them, hence the appropriateness of the phrase “architecture over water.” Indeed, China’s bridges are as much about architecture as they are about engineering in that they combine an inner logic and sense of aesthetics that is distinctive, while giving evidence of a sophisticated empirical approach to construction that equals practices and ingenuity known in the West. Bridge building in China undeniably is much more than a mere footnote in the chronicle of China’s contributions to world architecture and engineering.

Bridges sometimes are accidental configurations—a mere log or bamboo thrown over a channel as well as stones deposited by flood across the breadth of a stream—but more often they represent purposeful efforts to tease strength from materials in order to overcome a gap in space. Until recent centuries, bridge building anywhere in the world was a more practical and empirical art than engineering science. Primitive responses using common materials such as wood, stone, and rope of many types progressed over time into more complex solutions using exactly the same materials. Long before science and mathematics were consciously employed to design bridges, local craftsmen experimented with easily accessible materials nearby to solve their bridging needs. Yet, whatever the level of sophistication of the builder or designer, each was forced to consider fundamental and common realities that tested the nature and limits of various forms of matter. In addition, as elsewhere in the world, opportunities emerged in China for exploring and ultimately devising innovative methods of prevailing over old problems with art and grace using a rich range of technical solutions, many of which actually predated similar advances in the West.

Slender logs held together by iron staples and laid across a shallow running stream serve here not only as a temporary bridge but also as a convenient place to wash vegetables. Sanjiang region, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region.

The Basics of Bridges

It will be useful here to spell out some of the basic terms used in later discussions since bridge builders in China, like those anywhere in the world and whatever their sophistication, encountered common forms of matter while searching for, perhaps even stumbling upon, inspired solutions. Bridges are differentiated in a number of ways, namely in terms of their materials, structure, and purpose.

Simple bridges made of stone beams are ubiquitous in rural China, such as this stream going through Likeng village, Wuyuan county, Jiangxi. Because stone beams tend to bend due to tension, it is often necessary to support them with midstream piers to increase the distance crossed.Where fracturing occurs, traditional stone slabs are sometimes replaced by prestressed concrete slabs.

Traditionally, there were only three types of building materials—resilient wood, durable stone, and flexible ropes—and three types of bridge structures—beam, arch, and suspension. Cement, iron, and steel, among other later materials, came to offer new solutions to contemporary builders even as they continued to work within the traditional range of structural types and tried-and-true old material types. For the most part, the materials used to build bridges in the past were those that were readily at hand, whether they were timber, stone, or twisted ropes made of bamboo or vines. Yet, as many of the examples shown later in this book reveal, treasured hardwoods, marble, and pliant bamboo somewhat surprisingly came to be used in China in locations far removed from where these materials were commonly found.

The overall configuration of any bridge can be subdivided into its substructure, comprising abutments, piers, and foundations, as well as a super-structure that rises above—beam, arch, suspension, and truss, in addition to any number of combinations of these. Bridge structures differ primarily in the ways in which they bear their own weight, or dead load, as well as the live load—the weight of people, animals, vehicles, even snow. Forces and stresses—tension, compression, torsion, and shear—all impact how successful is the marriage of materials and form in the design and construction of any bridge. In some bridges, these forces act individually, but in most they act in combination, a subject that today is resolved by modeling, but in history was addressed by trial-and-error experimentation.

Tension and compression are opposite forces; the first tends to stretch or elongate something while the second pushes outward. In comparison, torsion is a twisting force, either in one direction while the other end is motionless or twisting in opposite directions. Beside “dead” and “live” loads, the force of the wind, rushing water, and earthquakes can all provide forces that create instability or, in fact, lead to the destruction of any bridge. Arches transfer most of the load they carry diagonally—rather than vertically—to the abutments, pushing outward against these supports rather than transferring their weight downward. In functioning this way, an arch is said to be in a state of compression, with its component parts squeezing outward.

Beams simply rest, with only gravity operating to transfer the weight of the beam and what it carries vertically to the supports on both ends, the abutments, and any midway piers placed to offer supplementary support. Because beams tend to bend at the middle due to downward pull, or tension, perhaps even to the point of breaking, there are definite limits to the length of single beams of different materials.

It is sometimes possible to overcome these limits by linking a series of short beams on intervening supporting piers or by projecting the beams by using cantilevering principles. Trusses, which are a form of complex beams, developed in the West in the nineteenth century, were not a solution experimented with by early Chinese bridge builders.

Since stone is very strong in compression, it is naturally the material of choice for building arch bridges. Sometimes called inverted arches, suspension structures are said to be in a state of tension since they pull inward and away from their anchorages. Used in ingenious combinations, beams, arches, and suspended cables can be employed simultaneously to support a bridge. It is all too easy to overbuild, to waste materials, money, and effort.

Step-on block bridges, where each stone is carved into a similar shape and lined up, are sometimes used to cross shallow streams, as seen here in Shouning county, Fujian.

Elizabeth B. Mock reminds us in her book, The Architecture of Bridges, that successful bridge building results from handling “material with poetic insight, revealing its inmost nature while extracting its ultimate strength through structure appropriate to its unique powers” (1949: 7).

In Europe, bridge building languished for eight centuries after the decline of the Roman Empire, not to be revived until the twelfth century. Famed for their extraordinary engineering feats, including bridge building, the Romans left a tangible legacy of stone works that are rivaled by those in China in terms of dates, styles, and geographic spread. Even exceeding in number those still standing in Europe, many examples of early Chinese bridge building innovations can be found throughout the countryside. H. Fugl-Meyer, a twentieth-century Danish engineer, confidently estimated that perhaps 2.5 million bridges existed in China in the 1920s, with as many as fifty-two bridges per square kilometer in some areas of the water-laced Jiangnan region (1937: 33).

Marco Polo himself noted the seeming ubiquity of bridges in Quinsai or Hangzhou, numbering, he said, some 12,000 bridges, an exaggerated figure that might have been inflated by a copyist.

In China, as in other countries, bridges figure not only in legends and myths but are also detailed as part of the material achievements of emperors down through the ages. It is said that the Sage Emperor Yu at the beginning of the third millennium BC summoned giant turtles to position themselves in a river as a means for him to cross. Early bridge builders, recognizing this precursor technique, used a continuous but broken line of large stones to accomplish the same purpose, forming “turtle bridges,” a type one can still see in shallow streams throughout the countryside.

As early as the twelfth century BCE, Shang dynasty texts began to employ the contemporary Chinese characters for bridge, qiao and liang, both of which include the wood radical, explicitly revealing that wood was a common building material for early bridges. Probably simple logs laid side by side rather than hewn timbers were placed across narrow streams or ditches surrounding settlements, as can be seen in the 7000 BP Neolithic Banpo site near contemporary Xi’an. Limited only by the height of available trees, spans were probably lengthened by using “turtle bridges” as piers. Even today in remote mountain areas, it is possible to see somewhat primitive piers built up of stones securely held in cages made of woven bamboo. It is not clear when either wooden or mortared stone piers began to be used to lengthen an effective span.

Along this garden path in a back area beyond Du Fu’s cottage in Chengdu, Sichuan, these step-on blocks have been molded to appear like lotus leaves.

Step-on Block Bridges

Unlike bridges that span open space in order to allow passage from bank to bank, block stone “bridges” actually take shape through sinking cut stones along a line within a streambed. Their precursor form often was simply a procession of large stones thrown into the water so that a walker could traverse the stream without getting wet. Most step-on stone block bridges or dingbu, as they are called in Chinese, comprise a single line of stones, some in their natural form while others have been chiseled into a shape. One of the most elaborate of these stepping-stone links is the 133-meter-long one at Renyang town in the southern part of Taishun county in Zhejiang. With 233 blocks, the passageway has the appearance of piano keys, with one set made of white granite placed higher, while the other lower set is made of darker bluestone. Passersby can step aside so that others may easily go by without slowing their gait, something necessary where heavy loads may be carried on a shoulder pole. Block stone “bridges” are a low-cost response to a critical need for dry passage across a stream. Rarely does floodwater destroy a line of stones of this type, and any movement is relatively easy to repair. Countless others of this type can be seen in the mountains throughout southern China.

Irregularly shaped stones collected from a nearby gorge are set into the streambed in an alternating pattern so that one foot of a pedestrian can easily follow another. Likeng village, Wuyuan county, Jiangxi.

Suspension Bridges

The longest and most sophisticated bridges in the world today are suspension bridges, with a lightness that far surpasses any bridge utilizing beams or arches to span space. China, which is a world leader in the design and construction of modern suspension bridges, has a long and continuing history. Early forms were relatively primitive ropes, hanging as a catenary curve, that were fastened to trees or anchored to stone counterweights on both ends. Pedestrians then could grasp or slide along the cables. In some areas, parallel ropes, held taut at different elevations, made it possible for walkers to tread on one rope while maintaining balance with the other, much like a tentatively supported tight-rope walker. Still other suspension bridges involved multiple cables fitted with cradles or baskets into which human beings, animals, or goods could be strapped and then swept across. Over time, suspension bridges evolved to include also a deck covered with wooden cross-planks. It is this last type, with suspended decking and at varying scales, that continues to be seen widely in the dissected mountainous areas of China. While suspension bridges have an inherent predisposition to sway, undulating in wave-like motions, they nonetheless provide an economical method of linking one side of a valley with the other.

Suspension bridges throughout the mountainous areas of southwestern China are made of thin wire “ropes.” The bed of the bridge, which is leveled with rough-hewn timber boards, follows the downward and upward arc of the load-bearing “ropes.” Additional “ropes” are used to lift the base “ropes” to prevent excessive sagging and to provide hand-holds for those crossing the swaying span. Anxian, Sichuan.

Villagers in mountain areas of Yunnan, as shown here, as well as those in eastern Tibet, traditionally fashioned narrow suspension bridges by fastening ropes made of rattan, a climbing palm with tough stems, to trees on both sides of a gorge.

Built in 1629 to span a ravine some 10 meters above the roaring Beipan River in Guizhou, this 50-meter-long suspension bridge was assembled from iron links coupled together into sets of parallel chains. The woodblock print highlights the number of temples and pagodas that populate the area at the rear of the bridge. A statue of Buddha is in the foreground.

With diminished mass, the grace of a suspension bridge arises from the lines that give it strength—plaited cables fashioned from bamboo, rattan, or other materials of vegetable origin. Marco Polo observed the making of “bamboo rope”: “They have canes of the length of fifteen paces, which they split, in their whole length, into very thin pieces, and these, by twisting them together, they form into ropes three hundred paces long. So skillfully are they manufactured, that they are equal in strength to ropes made of hemp.”

Although braided metal threads are common in fashioning cables today, iron chains were actually used in China as early as 206 BCE, an innovation that did not appear in Europe until 1741 and in North America until 1796. Among the most notable iron chain suspension bridges is the 113-meter-long Jihong (Rainbow in the Clear Sky) Suspension Bridge in Yunnan, which spans a gorge of the Lancang River and is said to have been crossed by Marco Polo. The bridge seen today was built in 1470. Some suspension bridges, like the Anlan (Tranquil Ripples) Bridge in Sichuan, discussed on pages 156–9, are composed of multiple spans supported by granite in order to overcome the sagging in a span of 300 meters. While cables once were made of braided bamboo, for the past thirty years they have been made of heavy-duty steel wires.

This unusual shigandang (Stone dares to resist evil) totem, with its colorful menacing face, is situated near the head of the suspension bridge to provide protection for the nearby village by preventing harmful influences from crossing the bridge. Anxian, Sichuan.

The dozen wrought iron cables and links which constitute the base of this suspension bridge, are anchored into the cement abutments sunken into the earth on both ends of the bridge. Anxian, Sichuan.

Beam Bridges

On the surface, bridges constructed using beams suggest simplicity and lack of distinction, merely wooden or stone planks laid from bank to bank. While many Chinese beam bridges indeed are straightforward and rudimentary, others are surprisingly intricate, even novel. Ordinary beam bridges, supported by intermediate poles and columns as well as crosspieces, are features commonly present in the pastoral scenes of Chinese paintings, reflecting perhaps their ease of construction and ubiquity in the countryside. Substantial beam bridges made of timbers and supported by stone piers are among the earliest bridge type described in Chinese historical chronicles, with a history that reaches at least to the second millennium BCE.

Qinshihuang, the first emperor of Qin who unified China in 221 BCE and is noted for his construction of walls and roads, also built notable beam bridges. During his reign, an imposing, multiple-span bridge—18 meters wide and some 544 meters long— was built near the Qin capital at Xianyang. Eight-meter-long timber planks were used to form each of the sixty-eight spans that rested on massive cut-stone columns sunk into the bottom of the Wei He River. During the Han dynasty that followed the Qin, at least two more large beam-type bridges and numerous smaller ones were built in the region around the flourishing imperial capital of Chang’an, just to the south of Xianyang. Several of these continued in use until the Tang dynasty, serving as important conduits along the fabled Silk Road. Piers of timber, stone, and iron as well as cylinders formed from bamboo containing rocks and earth, some dug into the muddy river bottom, supported bridges of this type. In a Han-dynasty tomb chamber, which was opened in today’s Inner Mongolia in 1971, a painted image of striking proportions of a wooden beam bridge crossing the Wei He River was revealed. Using rather slim stone columns and wooden beams, this bridge represents a type found widely in many areas of northern and northwestern China.

This rubbing from a carved brick from the Eastern Han period (CE 25–220) shows a horse-drawn carriage passing over a stone and slab wood bridge.

Just outside the imposing gate of the walled city, as depicted in Zhang Zeduan’s twelfth-century painting, Qingming shanghe tu, is a moat crossed by a broad bridge. Probably made of stone and wood beams, it clearly had sufficient strength and width to accommodate throngs of animals, humans, and carts. © Palace Museum, Beijing.

Shrouded in a misty atmosphere, this landscape painting titled Waters Rise in Spring by Shitao (1642–1707) features a common beam bridge using a trestle-like structure of slim poles and crosspieces. © Shanghai Museum.

Constructed of modular sets of supporting legs, cross-pieces, and wooden planks, long trestle bridges of this type are common in the villages of southern Anhui and northern Jiangxi.

Timber plank trestle bridges called zhandao have long been common in western Sichuan. Their construction involves sinking wooden substructures into nearly vertical cliffs in order to support the plank paths laid on them.

Not all wooden beam bridges spanned streams. Indeed, some snaked their way as timber trestle structures through inhospitable topography using building practices that improved upon those employed in shorter wooden beam bridges. Unrivalled in the world is the elevated timber plank bridge-road system that linked the cradle of Chinese civilization in the Wei He River valley of Shaanxi province in the northwest with the fertile Sichuan Basin in the southwest. Well known in Chinese history as the Shudao or “Road to Sichuan” and built at least as early as the Han period (206 BCE–CE 220), the wooden plank trestle bridge served as a channel of administrative, military, and cultural communication as well as trade for some 2,000 years across the formidable barrier of the Qinling and Daba ranges. Although the road fell into decay in the nineteenth century, portions of it are still used by local mountain dwellers to pass from one watershed to another and to avoid swiftly moving streams in narrow river gorges.

About a third of the 700-kilometer-long Linking Cloud Road, which forms a significant portion of the Shudao as it threads its way through the rugged Qinling Range, is actually comprised of wooden trestle shelves built out from canyon sides or astride streambeds. Termed gedao and zhandao, literally “hanging” bridges, timber plankways involved sinking wooden substructures into nearly vertical cliffs in order to support the plank paths. Herold J. Wiens, a geographer who studied the Shudao, explains that repairs and reconstruction taking three years during the Later Han period (CE 25–220) required the conscripted labor of 766,800 men working some 23 million man-days. During the Tang dynasty (618–907), the celebrated Buddhist monk Xuan Zang, accompanied by the Monkey King, wrote of zhandao as well as rope bridges, iron chains, and wooden ladders necessary to traverse the dangerous precipices of the region on his pilgrimage west. Structurally daring and indeed sometimes dangerous, trestle frameworks—with horizontal, vertical, and slanted supports—have even been employed in the building of imaginative temple structures on the sides of high precipices, such as the celebrated Hanging Temple at Datong in northern Shanxi province.

Stone beam bridges—most short but many comprising multiple spans—eventually became the most common and permanent bridge form in southern China. Resting atop piers of piled carved stone placed parallel to the flow of the stream, many stone beam bridges are quite simple, while many also are quite complex in that they are supported by massive pier structures built up within midstream cofferdams. Even a cursory examination reveals that stone beam bridges require more substantial abutments and piers than bridges built using timbers. Cantilevering the beams, as discussed below, made it possible to extend the span. The engineer Fugl-Meyer critiqued building in stone with his observation that “the Chinese bridge builder taxes his material to the utmost without allowing for any margin of safety. When a stone has a hidden fault... or when it is overloaded, it collapses without causing any surprise, and is replaced by a new stone of the same dimensions” (1937: 59–60). Metamorphosed granite, which varies in hues of gray and is rather coarse in texture, is the most widely used material for stone beam bridges.

The sprawling painting titled Emperor Minghuang’s Journey to Shichuan, a Ming copy after an original by Qiu Ying (1494– 1552), details the flight of Emperor Xuanzong and the imperial concubine Yang Guifei from Chang’an, today’s Xi’an, southward along the Shudao or “Road to Sichuan” in order to escape the An Lushan Rebellion of 755. © Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

This view is from atop the Bazi (Character Eight) Bridge, today covered in vines, towards a canalside neighborhood of low-rise dwellings that retains much of its traditional life.

Rather complex in terms of its scale and ingenious construction, the Bazi Bridge nonetheless is essentially a bridge constructed of long beams and smaller blocks of granite in carefully assembled stacks.

Perhaps the longest multiple-span stone beam bridge—one extant single segment has 150 spans with a total length of some 390 meters—is actually the remnant of a 1–2 kilometer-long towpath, called qiandao in Chinese. Overall, there are some 7.5 kilometers of stone paths still standing, a fraction of what once existed. These towpaths were constructed between 1862 and 1874 along the Xiaoshan-Shaoxing Canal in Zhejiang province to extend canal transport beyond the terminus of the Grand Canal at Hangzhou eastward to the seaport at Ningbo. The towpath thus served as a passageway for trackers who were needed to pull the heavily laden boats along. While the canal boats were usually propelled by sails or by sculling, sometimes it was necessary to tow them when strong seasonal winds made sailing difficult.

The gradual incline of a set of steps makes it possible for two adjacent canals to be connected.

As this model clearly reveals, the Bazi Bridge is actually a combination of two bridges juxtaposed so that it connects multiple lanes while facilitating canal traffic.

Some portions of the towpath were built immediately adjacent to land; indeed, at some locations trackers actually moved on land before reaching another stone pathway, but in others the towpath was very much like a bridge as stone beams supported by stone piers rose a meter or so above the water. In terms of materials used and techniques of construction, tow-paths differed little from common stone beam bridges that crossed streams. Each of the piers supporting the towpath is composed of a stack of granite blocks approximately 1.5 meters thick. Each span between them is made up of three or more rough-cut stone beams that exceed 2 meters in length and have a width of 3 meters. At intervals along the towpath, a section is elevated to permit the passage of small boats plying the intricate canal network of this region.

An outstanding and complex stone beam bridge with many components is the Bazi (Character Eight) Bridge in the southeastern section of Shaoxing, Zhejiang, a city that had in 1903 some 229 fine bridges along its 29 canals. The oldest extant urban bridge in China, the Bazi was constructed in 1256 during the later Song dynasty. Located to meet the needs of foot and water traffic at the junction of three canals and three lanes, the structure is actually made up of two juxtaposed bridges that are reminiscent of the Chinese character ba representing the number eight. The principal span clears 4.5 meters, rises some 5 meters, and has a width of 3.2 meters. Four-meter-long stone columns are slightly cambered to support the main span. The columns are themselves supported by a double layer of quarried stone 1.8 meters thick atop a foundation of stone boulders, which together constitute the support for the abutments. Including the balustrades and approach steps, the bridge is assembled from countless quarried slabs forming a structure of incalculable weight and substantial versatility that fits compactly into a tight residential environment. Overall the stepped approaches are gentle and have been modified to facilitate the movement of carts and bicycles.

With the tide in, the mudflats beneath the Luoyang Bridge in Quanzhou are submerged. The prow-like triangular cut-waters point upstream.

This is a remnant of a long nineteenth-century stone beam towpath along the Xiaoshan-Shaoxing Canal that extended water transport beyond the Hangzhou terminus of the Grand Canal. When there was little wind to fill the sails of boats, trackers on the towpaths used ropes to pull the heavily laden boats.

Handling large timbers and heavy stone columns set limits to what bridge builders could accomplish with available materials. In the middle two centuries of the Song dynasty (960–1279), extraordinary megalithic stone bridges built with granite piers and granite beams began to be built along the embayed shoreline of Fujian in southeastern China. The broad tidal inlets at the mouths of short turbulent rivers provided substantial challenges to spanning them with structures of any type, let alone utilizing megaliths. The methods employed in building massive stone bridges in Fujian remain a relative mystery, but there is no doubt that more than ordinary skills were required to maneuver stone slabs that reached 20 meters in length and 200 metric tons in weight. It is an amazing feat that stone beam bridges totaling 15 kilometers in length were constructed in a relatively brief thirty-year period alone throughout Fujian to help integrate an expanding transportation network. While there may once have been a bridge nearly three times longer, the Anping (Peace) Bridge, built between 1138 and 1151, is today heralded as “no bridge under the sun is as long as this one.” The bridge, which today is 2070 meters long, 10 percent shorter than it once was, was constructed using 6–7 granite slabs, each of which is 8–10 meters long, laid atop 331 stone piers. Another remarkable megalithic bridge still standing is the Luoyang Bridge, begun about 1053 and completed in six years. Today, only some 800 meters of the bridge’s original 1100-meter length and 31 of 47 piers remain. Some of the 11-meter-long granite slabs forming the deck weigh as much as 150 metric tons and were positioned using the ebb and flow of the tides. Bridge builders utilized an ingenious method of securing components of the stone foundations by employing living oysters as an organic mastic within crevices in the stone in order to strengthen the structure.

Built between 1138 and 1151 during the Song dynasty, the megalithic Anping (Peace) Bridge is even today more than 2 kilometers long. Over 330 piers of stacked carved granite lift heavy stone slabs of varying dimensions, some of which were infilled over time with smaller sections of stone because of the shifting that occurred in the structure.

Floating Bridges

King Wen, who laid the foundation for the Zhou dynasty some 3,000 years ago, is said to have made one of the earliest technological improvements over simple wooden beam bridges by lashing together boats to form a floating or pontoon bridge across the Wei He River. Employing side-by-side boats that then held up wooden planks, essentially beams laid transversely across the boats, floating bridges of this type became quite common in China as a means to span wide and deep, even swiftly moving streams. In general, pontoon bridges cope well with fluctuations in water level, variations in stream velocity, and the common need to accommodate navigation by other boats. At relatively low cost, pontoon bridges provided a relatively quick solution to a need in facilitating land transport. While small boats provide the support for most floating bridges, in China bamboo rafts, barrels, animal skins, wagon wheels, even calabashes have been used to support logs and planks. Pontoon bridges are usually formed a section at a time until the opposite bank is reached. In addition to cables and chains linking the boats together, “stones turtles”—woven containers of stone rubble—were sometimes dropped to the stream’s floor as anchors to moor groups of boats. Floating bridges demanded careful monitoring in response to river flow and traffic so that cables and anchorages could be adjusted to keep approaches relatively level.

In many parts of the world, floating bridges are viewed only as temporary structures, but in China many have endured for centuries. In one fashion or another, floating bridges made of linked wooden boats have stretched across the Gan River in Ganzhou, Jiangxi, since the Song dynasty. However, today only the Dongjin Bridge, with a length of 400 meters across 100 small wooden boats, remains. While most floating bridges provided only a mere walkway for pedestrians or simple wheeled carts, others in the twentieth century were capable of bearing vehicular traffic such as cars, trucks, and buses across two lanes. During warfare especially, pontoons were capable of being assembled quickly, serving a purpose, and then removed before they could be used by one’s enemies.

China’s most important rivers, the Huang He or Yellow River and the Chang Jiang or Yangzi River, both have several millennia-long histories of being spanned by precursor pontoon bridges, even as constructed bridges did not span them until the middle of the twentieth century. The Huang He saw its first floating bridge in 541 BCE and the Chang Jiang in CE 35, with dozens more built in the centuries following that utilized improvements in anchorages and connections. In Yongji county in southern Shanxi, the restoration of the Puji Floating Bridge during the Tang dynasty in 724 brought with it an especially noteworthy innovation—the use of heavy cast iron anchorages in the shape of large recumbent oxen that were secured with other weighty shoreline anchorages by a series of iron chains that replaced bamboo cables. Excavated only in 1989, these iron oxen were approximately 3.3 meters long, 1.5 meters high, and about 15 tons in weight, and were joined as well by life-size iron figures of men.

Each of the eight pairs of small shallow-draft boats is lashed together and connected with a stable pathway to form a pontoon bridge nearly 100 meters long in Pucheng county, Fujian. The intervening space between some of them is traversed merely by a series of parallel timbers that can be moved easily if a boat needs to pass.

Although rarely photographed, pontoon bridges of this type were created utilizing bamboo poles lashed together and then floated on the water. To ease passage on foot, a long mat made of thin slats of woven bamboo was laid across the floating slender bamboo poles.

In some ways, pontoon bridges are reminiscent of what takes shape in a Chinese tale of love regarding the Milky Way, which Chinese traditionally saw as a luminous “silver stream” in the heavens. On the seventh day of the seventh month each year, Niu Lang and Zhi Nu, a cowherd and a weaving girl, were allowed to meet when all the magpies on earth flew to heaven and formed a bridge over the galactic stream for them to cross and meet.

In this photograph taken in the 1930s somewhere in southern China, there is only one gap in the adjacent boats that can be opened for river traffic to pass through.

Cantilevered Beam Bridges

Simple wooden and stone beams have limits to the distances they can span, rarely reaching 10 meters. Each quarried stone or cut timber, the most common materials traditionally employed in cantilevered bridges, has an unspecified strength depending on the species and type. Even when they appear homogeneous, each usually contains invisible pockets of weakness. Downward pressures brought on by an increased live load can lead to unanticipated structural failure, the rapid breaking of the beam as it exceeds its ability to bend. It is not surprising then, that practical experience led to the doubling or tripling of beams in order to increase strength, and a sequenced layering in order to extend the range.

At the Chengyang Bridge in Ma’an village, Sanjiang, Guangxi, layers of protruding logs separated by transverse timbers provide cantilevered lifting for the covered bridge.

Chinese bridge builders began in the fourth century CE to employ the cantilever principle—the layering of counterbalanced beams with each set of segments supporting additional beams that reach out towards a midpoint—in order to extend the clear span. This approach involved projecting out horizontal arms of wood, then later stone beams from weighted abutments of piled stone or masonry. Since a gap usually still remained, this opening between them was then spanned with a beam or set of beams. Single-span cantilevered wooden bridges, usually using logs, were frequently built to cross relatively narrow ravines in Yunnan and Sichuan provinces as well as in remote areas of Tibet. In Gansu, even relatively shallow streams were bridged by structures that soared using a cantilevered superstructure.

Cantilevered stone beams are piled above the pier in order to lift the timber beams that support the corridor of the Dongguan (Eastern Pass) Bridge in Dongmei village, Dongguan township, Fujian.

The 33-meter-long Yongqing (Eternal Celebration) Bridge, built in 1797, is lifted by a single cut-stone pier with both stone and timber cantilevering. Above the central corridor is a substantial second storey used as a temple. Sankui township, Taishun county, Zhejiang.

Multiple spans of this type, each comprised of pairs of cantilevered supports, are found today in central and eastern China, especially in Fujian, Guangxi, Hunan, and Zhejiang provinces.

Among the most notable cantilevered wooden bridges in China are the “wind-and-rain” bridges or fengyu qiao of the Dong minority group in southern China. Although the most notable feature of fengyu qiao is the series of colorful pavilions lined along their continuous galleried superstructure, the support beneath is also outstanding since it is usually comprised of sets of massive cantilevered logs. The Chengyang Bridge is another good example. With a length of 77.76 meters and four 17.3-meter-wide openings set upon five piers, it was constructed between 1912 and 1924 in the Sanjiang region of the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. Three cantilevered layers of fir logs—a series of projecting horizontal beams 7–8 meters in length—are laid longitudinally across the top of each of the five stone piers. Between the four levels of cantilevered logs, which are held firm by tenoned timbers, are thin spacer logs that together stabilize the support and also provide some degree of flexibility. In this region, as elsewhere in southern China, when rebuilding of dilapidated cantilevered structures took place, the length of spans could be maintained by cantilevering more logs of shorter length than were originally used. The Lujiang Bridge in Hunan province, first built in the middle of the thirteenth century and rebuilt many times, at one point had ten layers of cantilevered logs to enable its span.

Activities along as well as in the water beneath an arch bridge crossing the Si River in Shandong province, are exhibited in this rubbing from an engraved brick of the Eastern Han period (CE 25–220).

Arch Bridges

Arches in many shapes and configurations, employing both stone and wood as materials, epitomize the superlative achievements of Chinese bridge building. Stone arch bridges are ubiquitous in China, but arches constructed of timbers, which are sometimes called “rainbow bridges,” are much more limited in their extent. Varying widely in form and in clear span, many arch bridges are merely functional and rather primitive, while others display not only astonishing design skills and techniques of construction but also express exquisite beauty. It is not known definitively when the first stone or timber arch bridges emerged in China but both forms developed independently of those in the West. Since arches are stronger than planks, whether the material is stone or wood, the evolution of arch forms made for the possibility of greater spans and heights. Arches are said to be in compression, pushing outward rather than transferring their weight downward as with planks, and as a result require substantial foundations.

Carved on the surface of a baked brick, this image depicts a horse-drawn carriage and a porter with a carrying pole crossing an arch bridge, which is reinforced with vertical supports beneath.

This tableaux of county scenes in Huizhou, found today in a temple near the Bei’an Bridge in southern Anhui province, includes a steep single-arch bridge with a pavilion atop it.

Although the scholars drinking in the wooded countryside are the main theme of Shitao’s early eighteenth-century Drunk in Autumn Woods, this virtuosic painting incorporates elements that could be found in a small park or garden, including a fine bridge, pavilions, and paths. ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Shown in this painting by a European is a somewhat fanciful bridge with billowing ornamentation above it that was clearly built so that large vessels, shown in the foreground, could pass easily beneath its soaring arch.

The Wanxian Bridge in Sichuan was photographed at the end of the nineteenth century by Isabella L. Bird, who stated: ”I have never seen so beautiful a bridge as the lofty, single stone arch, with a house at the highest part, which spans the river bed, and which seems to spring out of the rock without any visible abutments” (1900: 47)

The Dongshuang (East Paired) Bridge, perhaps built during the Song dynasty in Shaoxing, Zhejiang, is considered one of the finest single-arch extant bridges. Its mate, the Xishuang (West Paired) Bridge, no longer exists.

Stone Arch Bridges

In southern China, single- and multiple-arch bridges often rise precipitously above narrow canals, while others lay close to the water, with a continuous pattern of repeating arches from bank to bank, a form that is also common in northern China. Among the earliest representations of stone arch bridges are those of the Eastern Han period (CE 25–220) inscribed on fired brick tiles that have been excavated from underground tombs—themselves often constructed with arch ceilings—throughout northern China. In Henan province, a brick reveals an unadorned curved span being crossed by pedestrians, a mounted horse, and a carriage drawn by four horses with boats and fish beneath. The steep approaches are apparent, reinforced by the presence of muscular men towing the carriage up the deck, with others controlling the carriage as it descends.

The arch is a shape that carries its load outward as a result of compression that produces horizontal outward thrusts towards the bridge’s abutments. In spite of the durability of stone, moreover, Chinese stone arch bridges reveal a remarkable plasticity, a “resisting by yielding,” according to Chinese bridge builders. Throughout the Jiangnan region, where sandy soil made it difficult to sink solid foundations, bridge builders learned to make use of vertical sheer walls of stone slabs to receive those forces that might tend to deform the arch. The Chinese rarely used mortar as a bond between stones. Rather, stones were generally carefully shaped and sometimes mortised into each other or joined together by overlapping iron cramps. As a result of these techniques and the ensuing elasticity of the stone shell, stone arch bridges could tolerate a high degree of deformation without the bridge collapsing.

Located on a canal to the southwest of Suzhou in the small town of Mudu, this triple-arch span had a roofed structure on it that served to collect tolls from pedestrians who crossed the bridge.

At the end of the nineteenth century, countless arch bridges such as this one with its moon-shaped reflection, were found throughout the Jiangnan region around Suzhou.

One of China’s most beautiful arch bridges is the Taiping (Heavenly Peace) Bridge along the canal between Hangzhou and Ningbo to the west of the city of Shaoxing, Zhejiang. Built first in 1620 and then again in 1858, it is well known for its exquisite carved balustrades.

The lofty Wumen (Wu Gate) Bridge in Suzhou, Jiangsu, is located along the Grand Canal near the important Pan Gate. Said to date to the Song dynasty, it was rebuilt in the middle of the nineteenth century to a length of 63 meters.

Chinese stonecutters clearly accumulated experience that led logically to the development of different styles of bridges. Relatively crude semicircular single-arch spans can be seen in many areas of southern China, some of which are quite old. Many, however, are of more recent origin, the handiwork of local artisans who gather stones from nearby streambeds in order to fashion serviceable work-aday bridges as others did for centuries before them. Semicircular arches of dressed stone dot the Chinese landscape in large numbers. Descriptive names such as “horse’s hoof,” “egg-shaped,” “pot bottom,” and “pointed” are suggestive of other variations of elliptical and parabolic shapes. Some arches are polygons comprised of interlocked rectangular stone beams. Arches of this type echo similar ones found in Chinese tombs as well as gates through city walls, and even the Great Wall. While permitting a greater span than simple beams, polygonal beam bridges are, however, structurally weaker than true arch bridges. On the other hand, as the number of inclined stone beam segments in a multisided polygonal bridge increases from three to as many as seven, the structure begins to function much like a true arch bridge.

In the countryside of southern Huizhou, straddling the border between today’s Anhui and Jiangxi provinces, countless old stone arch bridges still serve today’s villagers. Although this bridge has a name, Qingjin (Celebrate Gold) Bridge, no information is available on its history.

A small unnamed single-arch bridge along the canal east of Shaoxing, Zhejiang.

Many stone arch bridges are infilled with earth and have seams between the cut stone that tends to allow dust to accumulate, filling the spaces so that, in time, seeds are able to germinate. As the roots of plants grow, they then have the capacity of loosening the stone blocks, shifting them sometimes to a point where gravity brings portions of the bridge down. It is not uncommon, even today, as can be seen in many photographs, for plants of all sorts to grow out from a bridge. In colder areas, moreover, these conditions are compounded because of the freezing and thawing of water that runs into or builds up in the seams, again with the means of dislodging the stone and leading to failure of the structure.

The Zhaozhou Bridge figures prominently in woodblock print culture throughout northern China, probably because of the association with Lu Ban, the patron saint of carpenters and builders, who is said to have built the bridge. After the bridge was completed, legend says that the Eight Immortals decided to cross it in order to test its strength. Lu Ban, fearing that the bridge might not support their weight, jumped into the water beneath to prop up the span with his outstretched hands. Both the polychrome and black-and-white prints from different workshops show variations of this theme.

Segmental Arch Stone Bridges

Among the most remarkable achievements of Chinese bridge building—indeed an advancement unrivalled in the world—was the creation of a segmental arch bridge at the end of the sixth century and beginning of the seventh century. This innovation, which predated similar forms in the West by 800 years—repudiated the convention that a semicircular arch was necessary to transfer the weight of a bridge downwards to where the arch tangentially meets the pier. The celebrated Zhaozhou Bridge, China’s oldest standing bridge and the oldest open spandrel bridge in the world, seemingly flies forth from its abutments. The double pair of openings piercing both ends of the arch spandrel, which at once accentuate its lithe curvature, lighten the weight of the bridge and facilitate the diversion of flood waters by allowing them to pass through the auxiliary arches rather than pound against the spandrels.

When this photograph was taken sometime before 1928, the Zhaozhou Bridge had been altered somewhat and there was sufficient water in the stream for vessels with sails to pass.

Although built more than 1,400 years ago, the Zhaozhou Bridge in Hebei appears like a contemporary bridge because of its low line and open spandrels.

Following the pattern of the Zhaozhou, also called Anji (Safe Passage) and Dashi (Great Stone), Bridge, no fewer than four were built in nearby areas of Hebei province where natural conditions were similar, while at least twenty others were constructed in northern China as well as in Guizhou and Guangxi. Until the middle of the twentieth century, the Zhaozhou Bridge was the longest single-arch span bridge in China. The restoration of the Zhaozhou to its original form and the building of similar bridges in recent times confirm that the Chinese recognize their early achievements in engineering technique and aesthetic expression. A masterpiece built almost 1,400 years ago, the Zhaozhou Bridge foreshadowed the elegance and scale of many contemporary bridges. In terms of economy of materials and aesthetic qualities, it is clearly the direct ancestor of the relatively light and lithe modern reinforced concrete bridges that dispense with stonework between the curvature of the arch and the flat deck above. As discussed on pages 123–7, the circumstances surrounding the construction of the Zhaozhou Bridge reveal the conscious attention to natural conditions, transportation requirements, and available materials, in addition to inspired creativity.

As with the Zhaozhou Bridge, each of the double sets of openings that pierce the arch spandrel on both ends of the smaller Yongtong (Eternal Crossing) Bridge reduces the weight of the structure and eases the flow-through of water during flood.

Multiple Arch Bridges

Multiple arch bridges are widely found in China, compelling evidence of both the diffusion of designs throughout the empire and the innovative skills of local bridge builders. Surprisingly monumental structures in what are today backward villages stand as a testament to the vitality of road and river transport in centuries past, the same commercial energy that gave rise to the magnificent mansions of merchants and gentry in out-of-the-way places. As with multiple-span beam bridges, arches were linked together to bridge greater distances than was possible with a single arch. Almost always an odd number, ranging from as few as three to as many as seventy, the duplication of spans almost always invokes pleasing rhythm with its repeating elements. Arch bridges with three spans are especially common in Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces in a region of a dense canal network. Soft alluvial soils in this low-lying region meant that bridges had to be relatively light. In addition, it was necessary for the bridges to rise rather high so as not to obstruct the passage of canal boats, many of which were powered by sails attached to tall masts. Unlike in the north, land transport of goods rarely involved carts or animals but depended upon individuals carrying shoulder poles who were capable of mounting steps as long as they could maintain their gait. Today, cyclists must dismount as they approach a steep bridge, but it is not difficult to push even a loaded bicycle up one of the ramps that have been added to the steps in recent times. Triple-arch bridges typically have a large central span, approximately 20 percent longer than the pair of identical smaller side arches. The two piers of such bridges are usually relatively thin given the spans they support, the load of adjacent arches being carried by the shared piers. Even though some triple-span bridges appear frail, insufficiently massive to carry the load of the arch shell, balustrades, and walkway, they are capable of substantial loads. Although only a small number of five-, seven-, and nine-span stone arch bridges survive, they differ little in structure from more modest three-span bridges, with loads being passed from one arch ring to another until reaching the abutments.

Records indicate that the longest multi-span thin-pier stone arch bridge, which crossed an arm of Taihu Lake just outside the city wall of Wujiang in Jiangsu province, was constructed in 1325 during the Yuan dynasty to replace a shorter wooden span on stone piers that had been built in 1066 and subsequently modified several times. Although called the Chuihong (Hanging Rainbow) Bridge, the structure did not soar. Instead, it was built only slightly elevated above the water except for several triple-arch segments that rose to facilitate the passage of vessels beneath. Until 1967 and the collapse of many sections, it stood as China’s longest multiple arch bridge at 450 meters with 72 spans. Only 49.3 meters and ten arches remain on the east end of the original bridge, today protected within a park. Restoration efforts continue to dredge up fallen arches, which then are added to the original span. Few Chinese bridges have received the accolades from poets and painters as has the Chuihong Bridge.

The 140-meter-long Ziyang (Purple Sun) Bridge in Shexian county, Anhui, is said to have been built during the reign of Wanli (1572–1620) in the Ming dynasty, but the bridge seen today was completed in 1835. Given its length and width, the bridge is a remarkably light structure, with eight stone piers and nine arches.

The Renji (Benevolent Aid) Bridge, completed during the Ming dynasty and rebuilt after a flood in 1868 with contributions from local folk, is 79 meters long and supported by four stone piers. With the equally old Pingzheng (Peaceful Governance) Bridge in the background, the pair is considered a place for townspeople to welcome the new moon. Qimen county, Anhui.

Close-up of the bow-shaped cutwaters of the 89-meter-long Pingzheng Bridge in Qimen county, Anhui. Records show the construction of bridges at this site during both the Song and Ming dynasties. After being destroyed in a disastrous flood in 1830, it was not until the nineteenth century that it was rebuilt. In 1974, the bridge was strengthened and widened.

Built first in the early ninth century, the Baodai (Precious Belt) Bridge is actually an elegant towpath extending 317 meters along the Grand Canal, which took its current form during the Ming dynasty. In addition to lengthy abutments that jut out from the shore, fifty-three arches cross open water for 250 meters.

Squeezed between modern structures, this triple-arch span is just one of many remarkable bridges in Jinze, a watertown now swallowed up in the suburbs of Shanghai.

No currently standing multiple arch bridge is longer than the Baodai (Precious Belt) Bridge, which spans 317 meters, with fifty low arches and three mid-span higher arches that permit boat traffic. As a low-lying bridge with thin stone piers, its appearance is said to resemble the jade belt donated by the governor who financed its construction. Built first in the early ninth century during the Tang dynasty, it took its current form about 1446 in the Ming dynasty. Adjacent to a broad section of the Grand Canal some 7 kilometers southeast of Suzhou, the replicated arches of the Baodai Bridge span the Dantai River as it empties into the Grand Canal. It was constructed as a link in a towpath which otherwise would have been broken because of the confluence of the two water bodies. The bridge was rebuilt in 1872 after a major collapse during the Taiping Rebellion, a subject discussed on ages 198–9, and restored in 1956. Once regularly visited to enjoy its technical achievements, today few seek out the bridge because of its remoteness, except during the Mid-Autumn Festival when the stone pavement affords a commodious space to view the full moon.

Accompanying a vocalist, the performer plays a traditional erhu, a long-necked instrument, near the five-arch Fangsheng (Liberating Living Things) Bridge in Zhujiajiao watertown in the suburbs of Shanghai.

No multiple arch bridge in China is more illustrious than the Lugou (Reed Gulch) Bridge, which was built at the end of the twelfth century. Because tradition tells us that Marco Polo described the bridge in 1289 as “perhaps unequaled by any other in the world,” it also is often called the Marco Polo Bridge. Once a raging stream flowed under the bridge, but today the broad streambed is essentially dry.

Taken early in the twentieth century, this photograph shows the Shahe (Sandy River) Bridge, also called the Chao-zong (Facing the Ancestors) Bridge, being crossed by a pair of two-wheeled donkey carts. Built in 1447 to replace a wooden bridge, the stone bridge is 13.3 meters wide and has seven arches spanning a length of 130 meters.

In northern China, the celebrated Lugou (Reed Gulch) Bridge has similar renown to that of the Baodai Bridge in the Jiangnan region. Built between 1189 and 1192 during the Jin dynasty, the bridge, with a span of 266.5 meters, was visited in 1280 by Marco Polo, who described it as “perhaps unequaled by any other in the world.” Building the bridge presented distinct challenges due to the fact that the often shallow Yongding River, which it crossed, usually iced over during cold winters in its upper reaches, and then in early spring disgorged ice floes made up of enormous blocks. To counter this, massive stone piers as well as boat-shaped cutwaters on the upstream side of each pier were positioned to deflect or break up the ice as it passed through the eleven arches.

Like other northern bridges, the Lugou’s deck is quite flat to facilitate the passage of carts pulled by human beings, mules, donkeys, horses, and camels. The 485 small stone lions that sit atop the capitals along the balustrades on both sides of the Lugou Bridge are one of its special characteristics.

The Lugou or Marco Polo Bridge is renowned for the countless lions with different poses atop each of the posts along its side balustrades. The old uneven stone surface that caused discomfort to those riding in donkey carts has been preserved while new level paving has been added along the sides. In the distance is the Guandi Temple.

Timber Arch Rainbow Bridges

Rainbow bridges—ingenious arches using “woven” timbers as the underlying structure—until recently were believed to have been lost in the twelfth century. The image preserved in Zhang Zeduan’s twelfth-century Song painting Qingming shanghe tu, usually translated as “Going Up the River During the Qingming Festival,” portrays an interlocked arch of piled beams that allowed large vessels to pass beneath its humpbacked 18.5-meter-long arch. With a width of 9.4 meters, the bridge provided ample space for one of the bustling markets of Kaifeng, the Song imperial capital. In recent decades, reports emerged of bridges with a similar structure—but with the addition of covered corridors—in the remote mountains of Fujian and Zhejiang provinces.

It is noteworthy that more than a hundred variations of covered rainbow bridges have been recently “discovered.” But it is a strange fact that no uncovered bridge with an underlying timber frame, like that shown in Zhang Zeduan’s scroll, has ever been located and documented.

Local people refer to the bridges that seem to rear up abruptly from their abutments and then soar dramatically cross steep chasms as “centipede bridges” because of their resemblance to the arch-like rise of a long arthropod’s body as it crawls. From a distance, these bridges appear to be supported by a type of wooden arch, but in actual fact it is an illusionary “arch” that emerges from the interlinking of a series of logs—long tree trunks—that function as interwoven chords or segments of the “arch.” Chinese engineers refer to such a structure as a “woven timber arch,” “combined beam timber arch,” and “woven timber arch-beam” to underscore the use of straight timber members tied together. The basic components are quite simple: two pairs of two layered sets of inclined timbers, with one set embedded in opposite abutments, stretch upward toward the middle of the stream. To fill the gap between these inclined timber sets, two horizontally trending assemblages of timbers are attached. Transverse timbers tenoned to them and/or tied with rattan or rope hold each of the sets of timbers together. It is these warp and weft elements that give rise to the term “woven.”

The downward pressure of the heavy logs compresses all the components together into a tight and relatively stable composition with a significant bearing capacity, the equilibrium can be upset if forces from beneath—such as might come from torrential floods or typhoon winds—push upward. To further stabilize the underlying structure, additional weight is added by constructing an often elaborate building atop the bridge. Somewhat counter intuitively, the heavy timber columns, beams, balustrades, and roof tiles add a substantial dead load that actually increases stability. With the addition of wooden skirts along the side perimeter, the wooden members are then also protected from weathering and deterioration to create a covered bridge. In the West, the covering of a covered bridge is always described as being added in order to protect the underlying wooden structure from weather, and never as added weight to stabilize the structure.

No “rainbow bridge”is more famous than the one depicted in Zhang Zeduan’s twelfth-century celebrated Qingming shanghe tu scroll, a section of which portrays an interlocked arch of piled beams permitting even large vessels to pass beneath its humpbacked opening. Along the surface of the bridge as well as in nearby lanes are busy markets. © Palace Museum, Beijing.

In 1999, in Jinze, a watertown suburb of Shanghai, a modest “rainbow bridge”was built as part of the NOVA television series to re-create the wooden substructure of the famed twelfth-century Qingming shanghe tu using ”woven” timbers to form an arch-like interlocking structure.

In 1999, an American television crew associated with the science series NOVA worked with a team of Chinese scholars and timber craftsmen to design and build a Chinese bridge. Believed at the time to be attempting something unknown except in a twelfth-century painting, the project successfully completed a model bridge that still stands in Jinze, a canal town on the shores of Dianshang Lake in the western suburbs of Shanghai. Working without plans and increasingly aware of how difficult the tasks were, the team experimented with materials and techniques to create an interlaced superstructure of beams placed under and over girders that meta-morphosed from a beam to an arch structure. Their bridge is a modest one when compared with those still found in southern Zhejiang and northern Fujian or even the one depicted by Zhang Zeduan.

Far surpassing this modest effort to create a rainbow bridge reminiscent of the one in Kaifeng are the numerous covered bridges with similar structures in Zhejiang and Fujian provinces, details of which are given on pages 218–47. A fine example, not discussed there, is Xianju (Home of the Immortals) Bridge, about 20 kilometers from the Taishun county town. Built first in 1452 and then rebuilt in 1673, it has the longest span of any bridge of this type in Taishun—34.14 meters—and an overall length of 41.83 meters. The bridge was spared when the highway was improved with an adjacent modern bridge. Rising like a slithering centipede, the covered gallery of the Xianju Bridge utilizes eighty slender pillars to fashion its nineteen internal bays. The rooftop ornamentation is especially notable.

Rising high enough for motorized vessels to move beneath it, Jinze’s newly constructed timber “rainbow bridge”joins many very old stone bridges along the nearby canals.

Covered Bridges

Many of the covered bridges in China are not rainbow bridges because they have underlying supports that differ from the woven timber arch-beam structure. The genesis of covered bridges in China, with traditions that predate covered bridges elsewhere in the world, is quite varied and the forms that are still seen are strikingly different from those that occur in Europe and North America. Covered bridges emerged in Europe in the fourteenth century, principally in mountainous areas in Bulgaria and Switzerland, before subsequently being built throughout the continent. While the few covered bridges remaining today in Europe are individually distinct and historically important, they generally do not have the aura of romance and nostalgia that wafts about covered bridges in North America. In the United States and Canada, covered bridges became common only in the first decade of the nineteenth century, subsequently becoming iconic elements of American rural and urban landscapes when horse-drawn vehicles dominated. Using patented truss designs, they proliferated until 1855 when the introduction of improved steel alternatives led to a dramatic drop off in their construction. Over the years, fire, flooding, vandalism, rotting, and overloaded vehicles swept away thousands of wooden covered bridges. Today, fewer than a thousand covered bridges remain of the 14,000 once standing in North America, where wooden covered bridges are universally recognized as worthy of preservation and valued as emblems of times past. Today, it is estimated that at least 3,000 covered bridges are in existence in China, a number that far exceeds those elsewhere in the world, and are among the oldest structures still standing. Yet, old bridges continue to be lost due to floods, typhoons, vandalism, fire, and replacement by modern bridges to meet current needs. It is often difficult to spot the ruins of old covered bridges because timbers and stone are usually quickly scavenged for use as building materials elsewhere.

While old photographs of bridges in China frequently pointed to the existence of small structures atop even single-arch stone bridges or to pavilions along longer bridges, rarely were large ostentatious structures photographed, probably because they were not encountered. Indeed, until very recently long covered bridges in China were essentially unknown outside China. Yet, whether the covered housing sits atop several stone columns, a series of brick or stone arches, a cantilevered wooden structure, or a “woven timber arch-beam,” it is now apparent that the Chinese constructed some of the most complex, most ornamented, and most beautiful covered bridges in the world. The renovation, rebuilding, and new construction of covered bridges in China have been increasing in recent decades. While many of these various types will be extensively discussed on pages 218–61, some will be introduced here.

Most covered bridges in China are constructed in exactly the same fashion as local houses and temples, using timber frame construction and a conventional set of elementary parts. The superstructure of the bridge serves as the “foundation,” with the floor of the bridge being paved with bricks or stone or overlain with sawn timber. Most covered bridges are I-shaped structures that are comprised of the number of bays necessary to span a particular distance. Often, as with land-based structures, the number of bays is an odd number since such numbers are considered auspicious. Wooden benches, some quite elaborately made, usually run along the full length of any covered bridge. Some of these covered bridges are analogous to roadside pavilions, differing only in that they span a body of water.

The covered corridor of the Santiao Bridge, Taishun, Zhejiang, is reminiscent of the wooden framework of common houses or temples. On the other hand, the underlying lifting structure is comprised of three sets of timber chords.

Said to have been built in the Tang dynasty, the Wo (Reclining or Holding) Bridge in Lanzhou, Gansu, served as a river crossing on the Silk Road. This mid-twentieth century photograph shows the bridge as it was restored in 1904, long before it became the prototype model for the Baling Bridge in Weiyuan.

Taken at the end of the nineteenth century, this covered bridge has an open pavilion atop it.Weizhou, Sichuan.

Long timbers laid horizontally on the stone abutments provide support for this modest covered bridge in the Sichuan countryside, which was photographed at the end of the nineteenth century.

Structurally a cantilevered timber bridge rather than a woven timber arch bridge, the Baling Bridge in Gansu is regarded as a “rainbow bridge.”

The Buchan (Stepping Toad) Bridge in Qingyuan county, Zhejiang, was first built between 1403 and 1424 and then rebuilt in 1917. Its single stone arch has a diameter of 17.8 meters while the corridor bridge itself has a length of 51.6 meters. Fifty meters away from the bridge is a stone in the water that is said to resemble the fabled toad in the moon, which led to the belief that one could reach the moon by crossing this bridge.

The Yingjie Temple Bridge in Jushui township, Qingyuan county, Zhejiang, is adjacent to a temple built during the Song dynasty, rebuilt in 1662, and then restored in 1850 to its current state.

Modest covered bridges like this one in Fujian are found throughout southern China, where they provide not only easy passage over a stream but also offer a place for farmers and travelers to rest.

The 15.1-meter-long Sanzhu (Three Posts) Bridge, Zhejiang, has a clear span of 10.1 meters. The horizontal logs that support the timber frame corridor are held up by three stone pillars sunk into the streambed.

Good examples of covered bridges of many types are found throughout southern Zhejiang and northern Fujian provinces. Taishun and Qingyuan counties in mountainous Zhejiang share characteristics with the neighboring Fujian counties of Pingnan, Shouning, Zhouning, Gutian, Fu’an, and Fuding, each of which has a large number of striking covered bridges.

Only three stone columns hold up the timber assemblage supporting the Sanzhu Bridge, a relatively short covered bridge, 15.4 meters long, in Xia Wuyang village in Taishun. Also in Taishun is the 36-meter-long two-storey Yongqing Bridge, whose structure includes a piled cantilever timber beam bridge set upon a single midstream pier. Just upstream of the Yongqing Bridge, one can still see the chiseled-out indentations in the rocky bottom of the stream into which a set of pillars once supported a precursor bridge. Although its origins are unknown—it was last restored in 1916—the covered corridor of the Buchan Bridge in Qingyuan county was constructed over a massive single stone arch. Built above a smaller stone arch, the Yuwen Bridge is sited well among old trees and a rambling stream. A path paved with smooth stones drops from the adjacent hillsides, suggesting that the bridge is an anchor site in a system of mountain–valley byways. The imposing set of altars on the upper level of the bridge affirms its centrality in village worship. The Yingjie Temple Bridge in Qingyuan county is adjacent to one of the oldest extant temples in the region, which was built during the Song dynasty and then rebuilt in 1662. Also a two-storied bridge structure, the Yingjie Temple Bridge spans a narrow stream atop a series of long, parallel logs. Richly ornamented inside, the bridge continue as a vital community center. Among the most outstanding covered bridges in Shouning is the Luanfeng Bridge in Xiadang township. Built first in 1800 and restored in 1964, the bridge has a clear span of 37.6 meters, the greatest of any timber bridge in China, and an overall length of 47.6 meters and width of 4.9 meters. Among other notable covered bridges are the Yongqing Bridge, Liuzhai Bridge, and Dongguan Bridge, each with its own local characteristics.

In terms of internal building structure, only a relatively small number of covered bridges utilize masonry walls for the enclosed structure, an example of which can be seen on pages 208–11. As in dwellings and temples throughout China, the pillars-and-transverse-tie beams wooden framework, called chuandou in Chinese, and the column-and-beam construction, the tailiang framing system, are used in constructing bridges. Both of these wooden framework systems directly lift the roof. The pillars-and-transverse-tie beams wooden framework is common throughout southern China, and has been utilized in the Buchan, Yuwen, and Luanfeng bridges. This framing system is characterized by pillars of a relatively small diameter, with each of the slender pillars set on a stone base and notched at the top to directly support a longitudinal roof purlin. Horizontal tie beam members, called chuanfang, are mortised directly into or tenoned through the pillars in order to inhibit skewing of what would otherwise be a relatively flexible frame. Wooden components, as will be seen in many photographs, are linked together by mortise-and-tenoned joinery, practices that can be traced back 7,000 years to Neolithic sites in eastern China. Column-and-beam construction involves a stacking of larger building parts: a horizontal beam, large in diameter and often curved, with two squat queen posts, or struts, set symmetrically upon it, followed by another beam and a culminating short post. Bracket sets are frequently used to extend the eaves substantially beyond the walls of the bridge. The Yingjie Temple Bridge utilizes the tailiang framing system, with heavier and more substantial columns as well as large horizontal beams.

Built in 1797, the Yongqing (Eternal Celebration) Bridge in Taishun county, Zhejiang, is a cantilevered bridge with piled timbers laid atop its single midstream pier. With a length of 36 meters, the bridge rises 5.2 meters above the streambed.

Timber frameworks of this type create a kind of “osseous” structure analogous to the human skeleton, which allows great flexibility, including structures that rise and fall as well as those comprising multiple levels. Because many covered bridges in China are also the sites of a shrine or temple, the roof structures are often more elaborate than those found on homes and are more like the roofs of temples. Ceiling structures are quite varied, especially near shrines and altars, where elaborately carved and painted coffered forms are common. With sawn timber cladding, the walling on bridges is generally simpler than that found on dwellings and temples.

Placed in a repeating fashion, sets of pillars and beams support the roof of the Yongqing Bridge.

Midway across the corridor, a set of wooden steps leads to the loft containing a variety of deities on several altars.

Much like the practices adopted in building houses, units of the wooden framework are assembled on the ground before being raised to a perpendicular location, where they are then propped and secured to adjacent segments by longitudinal cross members. As with Chinese house building, the raising of the ridgepole as well as some of the columns are important steps that are accompanied with ritual. With shrines and altars, covered bridges are transformed into active sites of worship, a subject discussed and illustrated on pages 72–5.

Garden Bridges

While the term “garden” in the West brings with it the notion of a relatively diminutive space with landscaped elements and structures created essentially for pleasure, this is only partially true in China. Here, gardens include not only small private gardens of literati scholars but also large imperial complexes that sometimes are as much administrative headquarters and parks as gardens. Monastery and temple precincts, imperial tombs as well as sprawling natural areas such as are found around Xihu, West Lake, in Hangzhou, may also be considered today as gardens. In all of these areas, there was an ingenious reproduction and spatial interplay of mountains, streams, ponds, trees, and rockeries as well as carefully designed structures such as halls, pavilions, galleries, and, of course, bridges.

In the canal-laced Jiangnan region in the lower reaches of the Chang Jiang or Yangzi River, many towns and cities are renowned for their literati gardens, sites for contemplation, study, and the cultivation of plants. As later chapters will show, bridges in these gardens provide passage but also offer invitations to tarry and ponder the meaning of poetic allusions embodied in buildings and natural vistas. Lined with low balustrades, simple stone beam bridges seem to rest on the water so that one can enjoy the lotus plants and the swimming fish. Zigzag bridges help extend the appreciation of a compact space by augmenting the distance between two points. Arch bridges have a scale and charm that invites one to pause and enjoy a view from above. In Yangzhou, the Wuting Bridge, also called the Five Pavilions Bridge and the Lotus Flower Bridge because of its resemblance to the open petals of the flower, is as much a pavilion as it is a bridge, a magnificent structure of substantial scale.

Taken just outside Shanghai’s Yuyuan Garden, this late nineteenth century photograph shows the fabled zigzag bridge and teahouse with its upturned eaves, which is said to have been the inspiration for the blue-and-white willow pattern porcelain exported from China to England during the last half of the eighteenth century.

Looking back from the tea-house across a wooden version of the zigzag bridge, the viewer sees the low-rise buildings and narrow lanes of the old walled city of Shanghai.

These contemporary views of the teahouse and zigzag bridge reveal in the distance the futuristic skyline of modern Pudong. In pools such as this one, teeming goldfish are believed to keep the water from stagnating, thus promoting the movement of positive qi, the life-giving force.

While the imperial gardens, hunting preserves, and parks in and around capitals such as Chang’an and Kaifeng have all been destroyed, existing only in literary texts, paintings, and memory, Beijing, which served as the imperial capital of the Ming and Qing dynasties for more than 500 years, is enriched with many fine examples. These include what came to be known as the “Western Seas,” the linked southern, middle, and northern lakes along the western side of the walled Purple Forbidden City. Although these interconnected bodies of water have few bridges, several are distinctive and can be contrasted with smaller spaces with bridges within the walls of the palace complex. Today, in the northwestern suburbs of Beijing, it is possible to visit and appreciate some of the imperial garden complexes that developed especially in the eighteenth century but suffered grievously during the middle to late nineteenth century, only to be reborn in the century that followed.

Known as “Garden of Gardens,” this area includes not only the vestigial remains of the once glorious Yuanming Yuan but also the grand Yihe Yuan, known to Westerners as the Summer Palace, a late nineteenth-century reconstruction reborn through the efforts of the Empress Dowager Cixi. The disposition of hills, causeways, canals, and islands connected to Kunming Lake made possible the creation of some thirty bridges, some imposingly grand and others quietly simple. Imitating the famed Su Causeway along the western side of West Lake in Hangzhou, is a causeway along the west side of Kunming Lake replete with six bridges, four of which are capped with pavilions. “Borrowing” scenes from the surrounding hills and sky beyond, just as with much smaller gardens in southern China, bridges were sited to capture the vistas and serve as a component of a panoramic scene as well. Perhaps the most elegant is the Yudai (Jade Belt) Bridge, a humpbacked feature that rises high like a breaking wave. On the opposite side of the lake is the magnificent Seventeen Arches Bridge that reposes like a symmetrical 150-meter-long rainbow as it rises slowly to a crescendo before diminishing. Hundreds of carved lion figures sit atop the balusters of the bridge. Clearly examples of human ingenuity and artistic sensitivity, these bridges continue to inspire the poetic imaginations of visitors, stirring images and reminiscences that link them to the interwoven fabric of China’s enduring civilization.