Читать книгу The Peranakan Chinese Home - Ronald G. Knapp - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

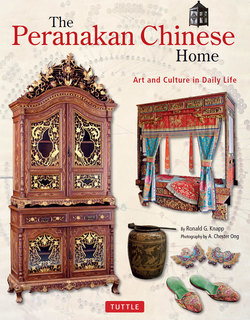

ОглавлениеThis recently restored century-old three-storey terrace residence presents a brightly decorated facade, with an ornate pintu pagar swinging fence-door, a pair of surname lanterns, a jiho wooden board above the door with characters proclaiming “The Glory of the Lineage,” and additional pictorial and calligraphic ornamentation. Wee family residence, now Baba House Museum, Neil Road, Singapore.

There is no single house type that can be described as exclusively Peranakan Chinese. Like Peranakans themselves, Peranakan housing developed with many variations that reflect place, time, and economic circumstances. Moreover, as the twenty-first century begins, the Peranakan Chinese residences that are still standing represent only a fraction of those built in the past when the community thrived. Thus, unfortunately, the surviving examples do not provide a sufficiently large enough sample to establish clearly whatever characteristics might have once distinguished them from the residences of others.

Peter Lee and Jennifer Chen in The Straits Chinese House adroitly demonstrate the adaptability of the Peranakan Chinese that made it possible for them to enjoy “a lifestyle both deeply rooted in Chinese tradition, and receptive to the cultures of other local communities” (2006: 20). This is indisputable and has contributed significantly to the maintenance of Peranakan Chinese identify, including some well-documented homes, over time. Yet, contemporaneous—and extant—late nineteenth and early twentieth-century residences of wealthy Chinese immigrants who were not Peranakan also reveal adherence to Chinese tradition while incorporating eclectic, opulent, and fashionable elements similar to those found in Peranakan Chinese homes at the time. As the sections below suggest, the fine homes of Tan Yeok Nee in Singapore, Tjong A Fie in Medan, as well as Cheong Fatt Tze and Chung Keng Quee in Penang, among many others who were immigrant Chinese, saw their homes as statements of their cosmopolitan nature even as some of them took local wives and thus began to establish Peranakan Chinese households.

Whatever similarities can be discerned when comparing Peranakan and non-Peranakan residences, however, striking differences are detected once focus is put on family life within the homes of each community, which admittedly were not homogeneous. As the nineteenth century ended, the cultural markers for successful Peranakan Chinese that distinguished them from non-Peranakan Chinese included speaking a Malay patois, schooling in English or Dutch, participating in life-cycle events such as twelve-day weddings and matrilocal marriages, as well as having distinctive clothing, porcelain, jewelry, and cuisine, among others. In addition, surface colors, furnishings, and ornamentation differed from one community to another. Photographs in the following chapters will present not only artifacts that are distinctively Peranakan Chinese within their homes, but also to some degree compare them with non-Peranakan Chinese homes.

Section drawings for what may have been the last fully Chinese-style residence constructed in Singapore at the end of the nineteenth century for the Fujian immigrant Goh Sin Koh. Later converted into an ancestral hall, this grand courtyard residence was demolished in the 1980s. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Set among a bounty of classical pilasters and arches amidst heavily ornamented plaster reliefs, Mandalay Villa was the home of Lee Cheng Yan, who was born in Malacca but moved to Singapore where he prospered in trading and finance. Constructed in 1902 as a two-storey bungalow in the Peranakan area of Katong in eastern Singapore, it was but one of several seaside villas built for the expanding family. The residence was demolished in 1983. A detailed discussion of family life in this residence is provided by Lee and Chen, (2006: 24–31). Artist: A. L. Watson. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

While there is archaeological and historical evidence of Chinese traders reaching many of the lands that rim the South China Sea more than a millennium ago, as mentioned in the Introduction, it was not until many centuries later that Chinese immigrants were able to construct homes reminiscent of those in China. In the meantime, Chinese traders built simple homes for the local women they took as wives, starting peranakan families during their annual hiatus while waiting for the shifting of monsoonal winds that would allow them to voyage back home to China where they also usually maintained families. For the most part, these initial homes likely were indigenous-style timber structures with thatched roofs of attap (fronds of the nipah palm), with walls covered with matting made of palm-like pandan leaves. Probably little of the furnishings or ornamentation in these early homes was rooted in Chinese traditions.

By the beginning of the fifteenth century, however, Chinese immigrants began to settle in increasing numbers along the coasts of the Malay Peninsula, even as annual sojourning continued for others. Similar migration patterns took hold along the coasts of many of the sprawling islands in what is today called the Indonesian archipelago. By 1678, when Chinese represented one-fifth of Malacca’s population, they lived in 81 brick and 51 attap dwellings in the town itself, with more elsewhere along the shore and inland (Purcell, 1965: 241). According to Francis Light, there were about 3,000 Chinese in Penang in 1794 who “possess the different trades of carpenters, masons, and smiths, are traders, shopkeepers, and planters” while others were squatters and workers opening up virgin land outside of town (“Notices of Pinang,” 1851: 9). With skilled construction workers and an increasingly diverse population with different needs and financial resources, Chinese over time built dwellings in Malacca that were progressively substantial and permanent, indeed quite similar to those in their home communities in China.

Five-foot way passages: Jonker Street, Malacca, then three in Emerald Hill, Singapore. Lee Ho Yin’s drawing reveals the evolution of shophouses from the early nineteenth century through the 1930s (2003: 133).

A colorful row of terrace houses built in the 1920s along Koon Seng Road, Joo Chiat, Singapore, which have been described by Julian Davison as “Rococo with a dash of Chinoiserie” (2010: 130).

After Stamford Raffles signed a treaty in 1824 that led to the establishment of a trading post on the island of Singapore and the formation of the Straits Settlements in 1826, Chinese from both Malacca and China arrived in escalating numbers, reaching more than 100,000 by 1869. Yet, according to Siah U Chin [Seah Eu Chin], housing for newly arrived Chinese in the late 1840s in Singapore continued to “resemble in a great measure the houses of the Malays, but there is this difference, that the houses of the Malays are mostly raised above the ground, whereas those of the Chinese are low on the surface; the walls of the houses are formed, some of the bark of trees, some of kadjang, and others of dried grass; some cover their roofs also with dried grass; those who are in pretty good circumstances use thin planks for their walls, but there are very few such. Except for the temples, none of the Chinese houses are covered with tiles” (1848: 288). Residential and commercial construction nonetheless continued apace in Singapore as Europeans and Chinese transformed swampy lands into productive agriculture estates, increasing not only wealth but also the desire to transform wealth into fine homes. As architects and draftsmen planned residences for the wealthy to meet new social and economic demands, they incorporated structural concessions that acknowledged the tropical climate of the region. Self- designed dwellings gradually decreased in town while continuing to be built in rural areas (Lee Kip Lin, 1988: 53–85). Similar patterns occurred in the Dutch East Indies, Siam, Vietnam, Cambodia, and the Philippines, each with its own design and temporal characteristics.

By the late nineteenth century, five distinct house types had emerged throughout the Nanyang or Southern Seas region: shophouses, terrace houses, detached villas, courtyard mansions, and bungalows. None of these types was the exclusive residential form for any single group. While today some are identified more with Peranakan Chinese, others, such as pure Chinese, indigenous peoples, and British and Dutch colonialists, occupied similar residences as well. Peranakan Chinese, on the other hand, in time introduced layers of color, furnishings, ornamentation, and function that made many individual residences identifiably and uniquely Peranakan. Peranakan Chinese, arguably to a greater extent than even wealthy Chinese immigrants who were similarly cosmopolitan, enthusiastically embraced Western and Malay elements even as they expressed an inherent Chineseness in their homes. Peranakan Chinese residences thus often differ in their degree of eclecticism from the homes of non-Peranakan Chinese. Detailed discussions of the variety of residential types occupied by both Peranakan Chinese and non-Peranakan Chinese families are presented in my Chinese Houses of Southeast Asia: The Eclectic Architecture of Sojourners and Settlers (2010).

Both Western and Chinese elements appear on the façades of shophouses and terrace houses. From left: Tan Kim Seng residence, now Hotel Puri, Heeren Street, Malacca, Malaysia; Cedric Tan residence, Tranquerah Road, Malacca, Malaysia; Persatuan Peranakan Cina Melaka (Peranakan Chinese Association of Malacca, Heeren Street, Malacca, Malaysia; Blair Road, Singapore; Emerald Hill, Singapore.

The Blair Plain area was developed in the 1920s. With colorful façades and quiescent charm, the Blair Road neighborhood has undergone significant gentrification in recent years.

SHOPHOUSES

No generic architectural form is more characteristic of Chinese domestic life in the maritime towns of Southeast Asia than the shophouse, a form whose origins can be traced back to southeast China, the home region of most immigrants. Its narrow and deep shape punctuated by skywells, load-bearing party walls, and an overhanging upper floor that provides a covered walkway along the front together characterize the shophouse as a remarkably utilitarian, versatile, and economical building type. Moreover, shophouses afford conditions for making a living in which all members contribute to the enterprise while carrying out family life within a single structure. With commercial space on the ground floor opening on to the street and living spaces behind and upstairs, rows of contiguous shophouses were able to meet the needs of generations of Chinese immigrant merchants and artisans, some of whom formed Peranakan families. Other non-Chinese shopkeepers and tradesmen also came to value this type of building where they could display wares easily on outdoor shelves and where they could work in an area with better light and fresher air than inside. The earliest shophouses had nondescript façades with minimal ornamentation.

A modest two-storey shophouse from the late 1700s at No. 8 Heeren Street in Malacca, which has been restored, reveals well the functional components that were integral to later, larger shophouses as the form evolved to meet changing needs (Knapp, 2010: 42–5). Late nineteenth and early twentieth-century photographs reveal both the consistency of the early shophouse form as well as its many local variations. While the earliest forms of utilitarian timber shophouses with attap roofs disappeared long ago, temporary buildings using the same materials are found in small towns throughout the region. Extant examples can still be seen in small towns in Indonesia, such as Tanjung Pura and Medan on Sumatra, and Lasem, Rembang, and Semarang on Java, each of which had substantial Peranakan Chinese communities. Where economic development had not yet erased them, many old shophouses constructed of brick and mortar and covered with roof tiles have continued in use as convenient warehouses.

While early shophouses were rudimentary and generally lacked external ornamentation, over time they became increasingly elaborate and ostentatious as the form evolved. John Cameron described the “native part of the town” of Singapore in the middle of the nineteenth century as having “buildings … closely packed together and of uniform height and character. The style is a compromise between English and Chinese. The walls are of brick, plastered over, and the roofs are covered with tiles. The windows are of lattice woodwork, there being no glazing in this part of the world. Under the windows of many houses occupied by the Chinese are very chaste designs of flowers or birds in porcelain. The ridges of the roofs, too, and the eaves, are frequently similarly ornamented, and it is not an unusual thing to see a perfect little garden of flowers and vegetables in boxes and pots exposed on the tops of houses. Underneath run, for the entire length of the streets, the enclosed verandahs of which I spoke before” (1865: 59–60).

Throughout the nineteenth and well into the twentieth century, the prototypical shophouse structure continued to evolve from its original form, a shop-cum-house. In time, some shophouses came to serve only as residences without any commercial function. British colonial ordinances in the Straits Settlements helped to standardize shophouses by mandating the use of fireproof materials and introducing the continuous veranda-like covered walk-way known as the five-foot way. Interior floor plans changed little over the years, even as widths grew broader and heights increased as reinforced concrete beams came to replace timbers in new construction. As this evolutionary sequence played out, styles changed, but only small numbers of new and larger commercial shophouses incorporating residences within them were built. Older shophouses that had met the needs of earlier generations of immigrants continued to be used, but now were often subdivided into cubicles that provided crowded sleeping space for ever-increasing numbers of poor Chinese immigrant laborers. Thus, instead of a family living behind and above an old shop, the residential space came to be packed with single men, each of whom was hopeful of pursuing the same get-rich optimism of earlier generations of immigrants.

This demographic transition brought with it the movement of some established Peranakan and non-Peranakan Chinese families from downtown to more salubrious distant areas. Pure Chinese immigrants setting out to fulfill their own dreams often replaced those who moved. Meanwhile, as unsatisfactory and unhealthy overcrowding in Singapore’s Chinatown worsened, the colonial government began to address issues of water supply, refuse collection, and limited fresh air in the ram-shackle commercial core of the city. “An important innovation was the introduction of a backlanes scheme, the idea here being to open up a corridor between the densely packed terraces of back-to-back shophouses, thereby bringing to their occupants ‘the blessings of light and air’” (Davison, 2010: 120). With these improvements, shophouses reached a new level of functionality that substantially enhanced their intrinsic character as an adaptable space for work and living. Today, throughout Southeast Asia, as in China, shophouses continue to be a vital component of the commercial cores of towns and cities. Although few shophouses are today occupied by laboring Peranakan Chinese families, some old shophouses—and terrace houses as discussed below—have been converted into boutique hotels, B&Bs, restaurants, specialty shops, and townhouses that proclaim the vitality of a once-diminishing Peranakan heritage in those areas of towns with tourism potential.

The doorways from the broad veranda into the residences, which are often left open during the day, are complemented by a perforated metal design above that draws air into and through the Han and Thalib residence, Pasuruan, Indonesia.

A multiplicity of styles characterizes ventilation ports on the exterior walls of Peranakan and other Southeast Asian homes. From left: Padang, Indonesia; Penang, Malaysia; Emerald Hill, Singapore; Phuket, Thailand; Emerald Hill, Singapore; Syed Alwi Road, Singapore.

TERRACE HOUSES

As a truly versatile structural form, the shophouse archetype morphed relatively easily into what can be called a row house or townhouse, serving exclusively as a residence without any commercial purpose. In many areas of Southeast Asia, it is now common to call side-by-side structures whose roots are in the shophouse tradition, but that serve purely residential functions, terrace (or terraced) houses. This nomenclature conforms to long-standing usage in the United Kingdom and is the convention employed here. The fine book by Julian Davison titled Singapore Shophouse (2010) delineates well the elastic nature of the term “shophouse” and the full evolutionary scope of its many manifestations, including “terrace houses.” Curiously, well into the early decades of the twentieth century, the working drawings of architects in Singapore continued to include the generic designation “shophouse” to describe terrace residences even when such buildings no longer incorporated a “shop.” Thus, it is not surprising that many observers even today consider any narrow and long structure aligned along an urban street a “shophouse,” a lingering inexact and anachronistic term, especially when the building is exclusively a residence.

With heightened immigration from China as the nineteenth century ended, as mentioned above, the core of Singapore’s Chinatown became overcrowded, congested, and unsanitary. Swapping convenience for improved quality of life, some prosperous Peranakan Chinese and pure Chinese merchants and entrepreneurs began to move to newly developing residential neighborhoods along Neil Road and Blair Road to the west, as well as River Valley Road to the north of the core of the original Chinatown. As still can be seen today, many of these terrace house residences have façades with Chinese-style ornamental patterns expressed in applied stucco reliefs and on decorative panels. A fine example of this form is the Wee family home, which was constructed along Neil Road in 1895 as one of a sequence of attached terrace dwellings. After a century’s occupancy over six generations by the Wee family, the residence was acquired and restored with a generous gift from the daughter of Tan Cheng Lock, Agnes Tan, to represent how a Peranakan Chinese family lived in the 1920s. Since opening in 2008 as the Baba House Museum, visitors are able to understand Peranakan home life in a comprehensive fashion that complements well the more formal exhibition of objects displayed in the galleries of the Peranakan Museum.

Until the late nineteenth century, commercial shophouses had been constructed generally by Chinese craftsmen under the supervision of local Chinese and Indian contractors who replicated existing buildings with the assistance of readily available pattern books. In time, architects who were beginning to design rows of residential terrace houses and some commercial shophouses in Malacca, Penang, and Singapore, began to introduce European-inspired elements. With the addition of classical Grecian columns and pilasters as well as Georgian fanlights, according to Davison, some of the rows of shophouses “would not have looked out of place in either Cheltenham or Bath (two English spa towns celebrated for their fine Georgian architecture)” (2010: 103). While it is not always possible to uncover which of these homes were owned and occupied by Peranakan Chinese families since there were other Chinese and those of other nationalities who also resided in terrace homes, some have remained in Peranakan families for generations and thus have a clear patrimony.

By the early years of the twentieth century, the once remote Emerald Hill area in Singapore, which had been a nutmeg plantation, was subdivided into building plots. Although most of the developers and builders of fashionable terrace houses in Emerald Hill were Straits-born Chinese whose ancestors came from the Chaozhou area in Guangdong province, wealthy Peranakan Chinese families came in time to outnumber other Straits-born Chinese owners there (Lee Kip Lin, 1984: 5–6). Joo Chiat and Katong in the eastern portions of the island, which until the 1920s and 1930s had been dominated by coconut plantations, also came to prominence as Peranakan Chinese who were seeking pleasant places to live built richly ornamented terrace houses and shop-houses there. Many of the new terrace residences incorporated a private forecourt or yard with gateposts that separated the residence from the roadway rather than having a linked five-foot way. Even as there continued a consistency in the traditional shophouse floor plan, which met the needs of shifting family circumstances, building plots of terrace houses came to vary in depth and width to meet the differing economic circumstances of families. While the earliest structures rarely exceeded two storeys because of the limitations of building materials and the constraints of construction techniques, many began to be built to three and even four storeys as cement became the preferred building material. As the illustrations in this chapter reveal, external ornamentation varied considerably as they reflected whatever styles were in vogue at the time.

The second-storey bedroom has bars on the windows and wooden shutters that can be left open or closed according to the weather. Wee family residence, now Baba House Museum, Neil Road, Singapore.

The public face of any terrace house, even a shophouse is, of course, its façade, which can be viewed in isolation or as part of a continuous sequence of rhythmic elevations, incorporating mixed sets of architectural elements. As the twentieth century began, as has been described above, the architectural design elements on the exterior of both shophouses and terrace houses increasingly adopted aspects of European Classicism even as Chinese motifs also had a place. Gretchen Liu describes this trend as “freely plagiarising Western architectural motifs,” while also adopting Malay-style fretwork and floral ornamentation as well as symbolic embellishment derived from traditional Chinese motifs (1984: 21). European-style stucco ornamentation that included draping swags often complemented Peranakan Chinese glazed tile motifs of colorful birds and flowers as well as richly Chinese symbolic motifs, such as deer, dragons, and qilin, which will be discussed in the next chapter. Terrace houses occupied by Peranakan Chinese and other Chinese had an added marker of Chineseness because of the pronounced use of Chinese calligraphy. The ground floor exteriors of many, if not most, terrace houses clearly expressed their Chinese personality with inscribed Chinese characters representing allusive maxims, a horizontal signboard declaring the family’s ancestral hometown in China, as well as pintu pagar half-doors with carved panels, subjects that will be discussed in the next chapter.

With circular ventilation ports above the latticed windows, this view is of a richly ornamented façade with a dentilated cornice, stucco detailing, and generous use of patterned wall tiles. Emerald Hill, Singapore.

The mixing of European aesthetic traditions with Chinese and Malay patterns created an architectural idiom referred to as “Chinese Baroque.” An extravaganza of in-filled exterior ornamentation, this idiom is occasionally an incongruous combining of patterns, materials, and motifs, which is judged by some as more dissonant than aesthetically harmonious. Sometimes compositions on the façade were fanciful and flamboyant, with jostled elements such as Chinese friezes, pintu pagar half-doors, Palladian-style fanlights, arched French windows, ornate Corinthian and austere Doric columns, intricate Malay fretwork and ventilation grilles, egg and dart molding, extravagant cornices, tropical timber louvers, glazed English tiles, and fluted pilasters and columns, among many other elements.

The placement of several registers of colored glazed tiles on the walls below the ground floor windows in Singapore, Penang, and elsewhere was a reworking of a pattern employed by Peranakan Chinese families in Malacca. While in China and early on in Southeast Asia the exterior colors of urban structures were almost universally lime plaster that ages into a mottled white and muted earth tones, more vibrant hues in time began to emerge in the Straits Settlements, first with ochre, green, and indigo. By the 1950s, the full color spectrum of pastel hues and vibrant colors generally associated with Peranakan Chinese dinnerware and textiles became quite popular. Unlike in Singapore, the changes were less dramatic in Penang and Malacca as was also the case in the Dutch East Indies. This profusion of repeating handcrafted and imported details continued until the end of the First World War. After the war, according to Lee Kip Lin, the buildings began to “shed their Chinese elements and decorations” and “assumed a more ‘Western’ appearance” (1988: 127).

The pintu pagar half-door can be employed to provide a modicum of privacy to those inside when the double-leaved door is open. Blair Road, Singapore.

Constructed in the late 1920s, this residence of Johnson Tan has undergone significant restoration. Its wall tiles, pintu pagar, jiho board, and abundant calligraphy are hallmarks of Peranakan homes of the time. River Valley Road, Singapore.

Wherever they appeared, such eclectic design borrowings created a distinct vernacular aesthetic that has worn well over time in spite of having fallen out of fashion for nearly a half-century. In residential as well as commercial buildings in the late 1920s and 1930s, in Singapore especially, interest turned to Art Deco designs, followed by a wave of post-war functionalism. These architectural trends not only affected new construction but also were applied in the “modernization” and general updating of some old terrace houses throughout the island. Others that were abandoned became dilapidated and ripe for later demolition. In the 1970s, within a decade of the establishment of Singapore as a city-state, extensive areas of old buildings were summarily demolished in order to facilitate urban renewal. These comprehensive urban renewal efforts included the construction of high-density public housing estates, which were emerging to meet a critical shortage of adequate domiciles for the country’s population in a country where land is scarce.

Beginning in 1986, the prior overemphasis on urban development was altered in Singapore as planners began to look seriously at conserving the island’s dwindling multicultural built heritage. Successful projects in gazetted conservation areas subsequently included the concentration of Peranakan Chinese terrace houses in Emerald Hill, Joo Chiat/Katong, River Valley Road, and Blair Plain. In these areas, historic terrace houses and shophouse structures were sensitively renovated as residences to meet the needs of discriminating owners who came to value the legacy of Peranakan Chinese even if they themselves were not peranakan. Today, both Joo Chiat and Katong are well known for the large number of surviving terrace houses and shophouses, rows of which are celebrated for their pastel and bold colors as well as rococo-like façades that mesh many styles. In February 2011, Joo Chiat was named Singapore’s first Heritage Town in recognition of its enduring Peranakan Chinese culture.

While neither Malacca, Penang, nor Phuket experienced the same economic vitality that drove many of the stylistic changes in Singapore, each enjoyed a similar evolutionary trajectory in terms of both shophouses and terrace houses, but within a more limited geographic scope. In recent years in the historical and residential areas of these three towns, efforts have been made to arrest the decline of traditional trades in shophouses even as there has been encouragement of those services that will help build the infrastructure necessary for sustainable cultural tourism. This has been accompanied by a celebration of their Peranakan Chinese heritage that is inextricably tied to surviving shophouses and terrace houses, among other cultural markers. The residential and commercial cores of Malacca and Penang, which include many Peranakan Chinese shophouses and terrace houses, were included in the listing of these two historic towns as UNESCO World Heritage sites in 2008. In recent years, community leaders in Phuket, which also has substantial Peranakan Chinese architecture, have debated whether pursuing World Heritage status would be a positive or negative factor in the further development of tourism on the island.

Colorfully ornamented second-storey façades: From left: first two, Emerald Hill, Singapore; second two, Syed Alwi Road, Singapore.

These efforts at the restoration of old shophouses and terrace houses are in striking contrast to an alternative use that is proliferating in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand. In towns throughout the coastal areas of these countries, structures that once were elegant terrace homes or serviceable shophouses have been transformed into “barns” or aviaries as breeding sites for dense colonies of swiftlets, small birds whose nests comprise layers of solidified saliva. Edible birds’ nests are a necessary ingredient in making bird’s nest soup, a delicacy appreciated by Chinese for centuries for its reputed therapeutic properties. While bird’s nest soup was once a culinary specialty enjoyed only by the very rich and the imperial family, the demand increased substantially in recent decades as China’s nouveau riche came to enjoy unparalleled prosperity that has been accompanied by a desire for expensive gastronomic delights.

Swiftlets, which once occupied seaside limestone caves exclusively, opportunistically found abandoned old shophouses and terrace houses suitable as alternative habitats because of their dark interiors and satisfactory range of temperature and humidity. Once entrepreneurs realized that swiftlets return season after season to the same spot where they had nested before to build a new nest, even if their past nest had been removed, they saw a bonanza in old buildings as lucrative venues for harvesting a highly valued commodity to help meet what is seen as an insatiable Chinese appetite for them. Nearby local residents along historic streets, such as the Peranakan Chinese enclave in Malacca, where swiftlet houses have proliferated, complained increasingly of noise from the birds themselves as well as chandelier-like sound systems that mimic the ambient twitter of swiftlets, multiplying bird droppings, and the fear of avian-borne diseases because of the proximity and number of swiftlet nesting houses. As the bird’s nest industry has burgeoned and objections increased within towns, new shophouses have been constructed in the nearby countryside that have commercial space for a small retail shop or workshop on the ground floor and “residences” for the birds on the upper floors. These new shophouses generally lack any exterior ornamentation.

COURTYARD MANSIONS

While modernizing influences, creative innovation, and changing fashion all contributed to the evolutionary patterns of shophouses and terrace houses, a remarkable and somewhat unexpected phenomenon emerged during the last third of the nineteenth century: wealthy Chinese immigrant entrepreneurs built authentic Chinese courtyard mansions and manors. Few of these immigrant success stories can be attributed explicitly to Peranakan Chinese, yet it is certain that some immigrant men from China did marry local women and thus produced children and descendants who indeed were Peranakan. As was the custom at the time, many of these rich men also had other wives and concubines at other locations in Southeast Asia as well as back in China. There is little in the written record of the women they married, thus it is left only to their residences to suggest the nature of their families.

Outstanding examples of these manors and mansions in Singapore and Penang in Malaysia, Medan and Batavia in the Dutch East Indies, as well as in Thailand, Vietnam, and the Philippines can be glimpsed in old photographs. Only a few are still in existence today. It is a curiosity that four of the individuals who built large mansions that are still standing also constructed grand retirement residences in their home villages in China (Knapp, 2010: 37–9). As prosperous community members who had close relationships with European government and business people, many unfailingly incorporated modern elements in their fundamentally Chinese mansions and manors for the enjoyment of their families just as was the case with Peranakan Chinese of similar social standing. To do the construction, specialized craftsmen from China came on long-term assignment, who then worked with already arrived immigrant laborers. Imported building materials came from China, sometimes as ballast in trading vessels, which then were integrated with plentiful local woods to create grand residences that would have been appropriate back home.

Batavia in the Dutch East Indies was a “Chinese colonial town under Dutch rule” from the eighteenth century onward with both Peranakans and totok inhabitants (Blussé, 1981: 159ff). While no Chinese residences from the eighteenth century remain in the city, which is now called Jakarta, there are some from the nineteenth century when Peranakan Chinese built many fine Chinese-style homes. Members of the Khouw family built three late nineteenth-century mansions along the fashionable Molenvliet West alongside older Dutch mansions and hotels. Only one of these three, which was constructed in either 1807 or 1867, survived well into the twentieth century, having followed a tortuous journey of being threatened with destruction to miraculous survival (Knapp, 2010: 172–9).

Another fine home in Jakarta still occupied by the Peranakan descendants of the family that built it is the Souw Tian Pie residence, which was constructed early in the nineteenth century by a successful community leader. While originally there were three parallel structures and a pair of perpendicular side wings to the structure, its overall scale was diminished over time as sections were demolished. Family memory recalls that the wooden members—columns, brackets, tiered trusses, doors, and windows—as well as those carved of stone—lions, stools, benches, and drums—were all crafted in China and sent to Batavia by ship for assembly and placement. Among these is a grand altar, which is still used daily for rituals, comprising three intricately carved tables set with statues of Guan Yin as well as the votive articles.

Some 20 kilometers to the west of Jakarta, in an area that once was covered with plantations farmed by Chinese immigrants, was the expansive home of Oey Djie San, which is said to date from the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century. When we visited the rambling estate in June 2009, most of the building was still standing, but by the end of the year was demolished in spite of the outcry raised by preservationists. What was remarkable about this Peranakan Chinese residence was that it actually comprised two back-to-back houses, one built in Chinese style facing the river, while the other, a Dutch Indische-style building with a trapezoidal roof and columned veranda, faced the road. Like many early Chinese houses in Indonesia, the structure included three parallel buildings with open courtyards in between. The first and third buildings were single-storeyed while the middle one had two storeys and was elevated on a slightly higher podium, with walls constructed of red bricks. Baked terra cotta roof tiles and square floor tiles were used throughout, with windows and columns made of local hardwoods (Knapp, 2010: 180–5).

Some of the most beautiful ceramic wall tiles grace the outside walls and pediments of gates of homes on Emerald Hill, Singapore, which was developed between 1902 and the 1920s, becoming in time a concentrated neighborhood of successful Peranakan Chinese.

Each of the columns that line a series of 1920s shophouses along Singapore’s Syed Alwi Road has inserts of individual flowers on the twelve ceramic tiles on each side.

No Chinese mansion in Indonesia is more impressive than the opulent one built by Tjong A Fie between 1895 and 1900 in Medan in the northern part of Sumatra. Tjong, a Hakka immigrant from Meixian in eastern Guangdong province, lived there with his third wife, a Peranakan Chinese, whose descendants still treasure the home as a museum of Peranakan Chinese culture. As a fine example of the cultural eclecticism of a Southeast Asian Belle Époque, it mixes the latest European-style furnishings, fine arts, culinary traditions, and the newest inventions with centuries-old styles of Chinese furniture, altars and rituals, food, and costume as a truly hybrid home for a family that had Chinese, European, and local identities. The residence includes sweeping rooms suitable for receptions, celebrations, and festivities that could be enjoyed as well with other important members of the community, whether indigenous royalty or international entrepreneurs and businessmen from the Netherlands, England, United States, France, Russia, Switzerland, Poland, Germany, and Belgium. Photographs of the interior of the house when it was first occupied reveal spacious rooms composed of both Chinese and European elements, which will be illustrated in the following chapters.

Queeny Chang, the eldest daughter of Tjong A Fie, left the only written record describing life in what she calls “Tjong A Fie’s Magnificent Mansion” when it was completed in 1900 (1981, 19–23 ff, 56). As the first residence in Medan to have electricity, not only was there no need to contend with oil or kerosene lamps, there was abundant illumination during the nighttime when circumstances demanded that it shine brilliantly through the front windows on both levels. Set back from the road in front, behind an imposing gate that led to a garden and broad porch, the exterior of the house had an overall modern appearance because of its large windows, square columns, and covered veranda. Yet, on closer inspection, the structure is a Chinese-style mansion with a symmetrical triple-bay plan and carved brackets lifting the roof. The pair of flanking side buildings have unmistakable Chinese gables. Early photographs show the entry porch with hanging couplets, lanterns, and inscribed boards (Knapp, 2010: 146–55). Photographs of the interior of the house when it was first occupied reveal spacious rooms composed of both Chinese and European elements.

Looking through the arch of a five-foot way is a glimpse of ceramic tiles on the walls as well as on the pavement. Emerald Hill, Singapore.

Pintu pagar and other doorways vary greatly in terms of wood and ornamentation in Singapore. From left: Blair Road; Emerald Hill; Emerald Hill; River Valley Road; Emerald Hill; Emerald Hill; Emerald Hill; Blair Road; Blair Road; Blair Road; Joo Chiat Road.

Imported cast-iron pieces are found in some Peranakan homes as column capitals and bases as well as ballustrades. From left: Tjong A Fie Mansion, Jalan Kesawan Square, Medan, Indonesia; Han Ancestral Hall, Surabaya, Indonesia; Emerald Hill, Singapore.

While a handful of Chinese-style manors were built in Singapore during the last half of the nineteenth century, there is insufficient evidence to determine whether Peranakan Chinese built many of them. This is because records that discuss descent focus on Chinese fathers to the exclusion of local mothers and rarely reveal the multiethnic character of marriages. Four mansions or Si da cuo were built by entrepreneurial immigrants with roots in the Chaozhou region of China: Tan Seng Poh, Seah Cheo Seah, Wee Ah Hood, and Tan Yeok Nee. Of these four, only Tan Seng Poh is heralded today as a Peranakan personality, but only the stately mansion of Tan Yeok Nee survives. The shipping magnate Goh Sin Koh, an immigrant from Fujian, built a fifth mansion. With its swallowtail ridgelines and red brick structure, Goh’s Fujian-style residence was probably designed and built by Chinese craftsmen, even though professional architects and draftsmen prepared drawings that had to be submitted for municipal approval. Tan Yeok Nee returned to China to live out his days in a mansion he also built there. When he died in 1902 at the age of 75 in China, his sons had all predeceased him, leaving eight grandsons to inherit his estate. It is unfortunate that we have neither photographs nor a surviving structure that would help us understand what Peranakan Tan Seng Poh’s da cuo or “mansion” looked like.

BUNGALOWS AND VILLAS

Bungalows and villas describe dwelling types introduced first to meet the needs of European colonialists in Asia, but in time were also adopted by non-Europeans. Over time, wealthy Peranakan Chinese and others adopted the bungalow form, especially as seaside residences, with a detached kitchen, nearby servants’ quarters, and a separate garage. Isabella Bird, the noted Victorian globe-trotter who visited Malacca in the late 1870s, caught glimpses of the rising prominence of Peranakan Chinese families and reflected on their lives shuttling between in-town terrace houses and their country bungalows, a lifestyle mirrored elsewhere in the Straits Settlements: “And it is not, as elsewhere, that they come, make money, and then return to settle in China, but they come here with their wives and families, buy or build these handsome houses, as well as large bungalows in the neighboring coco-groves, own most of the plantations up the country, and have obtained the finest site on the hill behind the town for their stately tombs. Every afternoon their carriages roll out into the country, conveying them to their substantial bungalows to smoke and gamble. They have fabulous riches in diamonds, pearls, sapphires, rubies, and emeralds. They love Malacca, and take a pride in beautifying it. They have fashioned their dwellings upon the model of those in Canton, but whereas cogent reasons compel the rich Chinaman at home to conceal the evidences of his wealth, he glories in displaying it under the security of British rule. The upper class of the Chinese merchants live in immense houses within walled gardens. The wives of all are secluded, and inhabit the back regions and have no share in the remarkably ‘good time’ which the men seem to have” (1883: 133).

Although the name “bungalow” is used today in Southeast Asia to describe quite elaborate suburban homes, even villas, those constructed in the later nineteenth century and early twentieth century were comparatively unpretentious. Early single-storey bungalows were constructed of brick and wood and are noteworthy because of adaptations to the tropical climate, especially to increase ventilation: raising the structure above the ground on substantial piers, adding a projecting veranda, broad eaves overhangs, ventilation grilles in the walls, roller blinds made of reeds for shading, large windows and doors, as well as constructing rooms with lofty ceilings. These features mimic to some degree indigenous Malay building traditions, however with materials that are more substantial. Floor plans were usually symmetrical. Over time, less wood was used in the construction of bungalows as reinforced concrete gained dominance because of lesser costs.

Examples of both Peranakan Chinese bungalows and villas still stand in Malacca, Penang, and Singapore, as well as in Phuket in Thailand and Yangon in Myanmar, although most are gone. These five port towns were linked not only by business interests but also via bonds between temples and personal alliances that facilitated intermarriage between and among Peranakan families. The fact that Chinese carpenters and masons shuttled from port to port also ensured that fashions diffused widely. With their greater populations, larger ports like Singapore and Penang also provided shops that sourced high-quality furniture and porcelains from China, molded iron columns and fences from Scotland, encaustic floor tiles from England and Italy, as well as furniture and decorative objects from sources all around the world. Lee Kip Lin includes a comprehensive gallery of bungalows and villas in Singapore built over a century ago, which were lived in by both Peranakan Chinese and Westerners, that reveal the range of their eclecticism (1988: 143–225).

In some cases in Singapore, Peranakan Chinese merchants such as Seah Song Seah also maintained two residences, a terrace house in the city and a villa in the country, that expressed their multicultural lives. Whether lived in by Westerners or Asians, the floor plan and overall form of bungalows and villas were essentially the same. Peranakan Chinese and wealthy Chinese immigrants, however, marked their homes with distinctive Chinese elements similar to those found on shophouses and terrace houses. On the exterior, they often placed a jiho board with Chinese characters above the front door, hung couplets alongside the door, installed a carved and gilded pair of pintu pagar half-door panels, and sometimes even decorative moldings that evoked Chinese themes. Inside, a prominent space was also found for two altars, one for deities and one for ancestors, and Chinese-style furnishings. Not all Peranakan Chinese residences though had the full range of these Chinese elements. In addition, because many Peranakan Chinese businessmen also interacted with non-Chinese, they also furnished some rooms in a Western, generally Victorian or Edwardian, style that they also came to enjoy. Displaying books in foreign languages and hanging pictures of European scenes expressed their cosmopolitan tastes.

Peranakan Chinese Seah Song Seah, a gambier and pepper merchant, as with other successful businessmen, maintained two homes. On the left is the home he had built in town on River Valley Road, which has housed the Nanyang Sacred Union Temple since the 1930s, and on the right is his country bungalow on Thomson Road, which has been demolished. (Wright and Cartwright, 1908: 636.)

Chinese-style courtyard houses with a single-storey front hall and a parallel two-storey rear hall, which were linked to a pair of perpendicular wing buildings, were built by Chinese immigrants and Peranakan Chinese throughout Southeast Asia. Only rare photographs hint at their scale. Molenvliet Street, Batavia, today’s Jakarta, Indonesia. Photograph courtesy of KITLV/Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies.

Fine examples of early twentieth-century bungalows constructed in the East Coast area of Singapore can still be seen. Some of the finer bungalows that were along the shoreline had an enclosed area for swimming built into the sea as protection against shark attacks (Lee Kip Lee, 1995: 42). In addition, both Europeans and Peranakan Chinese built large detached villas—some veritable mansions based on modest bungalows—but others adapted the styles of villas that were then in vogue in England and on the continent. In Baba Malay and Hokkien, these were collectively called ang moh lau “red-hair (European/foreign) buildings.”

Taken a century apart, these photographs reveal the eclectic nature of the Tjong A Fie Mansion, which was completed in 1900. A successful immigrant from Meixian in Guangdong province, Tjong began a Peranakan Chinese family whose members still occupy the home. Jalan Kesawan Square, Medan, Indonesia.

Just as there were stylistic differences as shop-houses and terrace houses evolved, this was true as well with bungalows and villas. While European classical features dominate on the façades, Peranakan Chinese added decorative stucco elements that recall themes then current with new generations of shophouses and terrace houses, “a hotch-potch of elements [that] do not seem to have been applied according to any architectural theory or principle,” in the words of Lee Kip Lin (1988: 128). Mandalay Villa, which was constructed in 1902 and demolished in 1983, was a grand two-storey eclectic residence built by Lee Cheng Yan, a prominent Peranakan Chinese merchant family, in the Katong seaside area of Singapore (see page 17). Set within an expansive garden that was approached by a long driveway, the residence had six bedrooms with a nearby sea-pavilion having an additional two bedrooms to accommodate an extended family that varied in size over the years. With verandas on the front and rear and spacious halls for dining and socializing, the home was often the site of celebratory events. Although no longer standing, Mandalay Villa is well documented with exterior and interior photographs that show not only its classical European features and furnishings but also its functioning as the site for a Peranakan Chinese wedding and a funeral (Lee Kip Lin, 1988: 192–3; Liu, 1999: 224–5; Lee and Chen, 2006: 24–31).