Читать книгу Akhenaten - Ronald T. Ridley - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

This is, I believe, the first book about Akhenaten written not by an archaeologist, a philologist, or an art historian, but by a historian. What that means should become clear as the text progresses.

I have tried to document each statement with evidence. That can come from an amazing array of sources: epigraphic, archaeological, artistic, or literary. I confess that finding them has often caused me great pains; for example, others can refer simply to ‘a block from Hermopolis’ (there are thousands and thousands of them), or an object in the Louvre or in the Metropolitan (the same). They are identified here as exactly as possible.

Each chapter is subdivided with subheadings. In this way, I have tried to avoid a common feature of writing on Akhenaten: nothing is treated comprehensively in one place, but each topic is scattered throughout the text with multiple references. With my system, one should find a substantial discussion of any topic in one place, with adequate signposting.

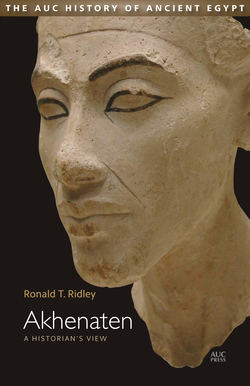

Illustrations are vital evidence. They will be found at the most important point where they are discussed, not in erratic order or bunched together at various points.

As a historian, I am not competent to deal with art history. There is no chapter as such on Amarnan art. And there is no chapter on the infamous problem of a coregency between Akhenaten and his father. After oceans of ink being spilled, that has most recently been nonchalantly consigned to the ‘outdated matters/no longer of interest’ box.

There are two matters I should signal. First, I had hoped to present the essential primary sources drawn from both text and art directly in my own text, as historians like to do, but they are hidden in the endnotes. Second, I have given full names in the first reference to each person in each chapter, but used only surnames for subsequent references in that chapter. On another matter of names, I have generally called Akhenaten and Tutankhamun by those names, rather than switching to and from ‘Amenhotep IV’ and ‘Tutankhaten,’ although I have, on occasion, highlighted a particular occurrence of a name where it is necessary for the purposes of the narrative.

My sincerest gratitude must be expressed to the original publishers of the wonderful illustrations without which such a subject would be incomprehensible, and who have so generously allowed them to be reproduced here.

There are three women without whom this book would never have been published: my best editor, my wife Therese; Ingrid Barker, who impeccably transformed typescript into a digital version; and Salima Ikram, the essence of kindness.