Читать книгу The Book of the Bivvy - Ronald Turnbull - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1 BASIC BIVVY

PEIGNE AND SUFFERING

On the way up, we met two other British people coming down. ‘Benighted: abseiled off: you’ll see our rope hanging in the chimney.’

Silly Brits, don’t understand Alpine climbing, always get benighted. We’d pick up their rope as we passed it and bring it back to the campsite that evening. Or that late afternoon – the Aiguille de la Peigne is one of the smallest of the Chamonix Aiguilles, good rock and Grade III (British Diff) all the way.

The trouble with guidebooks is that they’re written by people who are very good at it. Our book was an English-language selection. The English-language selectors had omitted the Ordinary Route up the Peigne in favour of this terribly easy but rather nice rock route. But there are 600m/2000ft of that terribly easy rock. This is fine if you consider English Diff a scramble and climb it unroped. It’s not fine if you consider English Diff a climb.

As we went up we looked at our watches, looked at the rocks above, and got less and less British and more informally Alpine in our climbing. We reached the previous people’s jammed rope and removed it from the chimney. We got to the top of the climb and crossed onto the ordinary route. We abandoned all idea of the summit and set off down the ordinary route. It got darker.

The trouble with downhill rock climbing in the dark is that you can’t distinguish the worn footholds, the trampled ledges, the turned-over screes of the correct line. So on a suitable rocky ledge we decided to stop and get benighted.

All night long we heard the meltwater dripping, so the temperature can’t even have got down to freezing. And we were equipped. We’d read all about it in The White Spider, and we’d gone in to get some of this sophisticated survival equipment. ‘I would like,’ I told them at Tiso’s, ‘a bivouac sack.’

They looked puzzled, then laughed. ‘Ah – you mean a polybag!’ Surprisingly for such an advanced bit of kit, the cost was only five shillings.

The five-shillingsworth were bright orange and rather thick. I wriggled into a cosy hole below some boulders. The other people’s rope, coils opened out into a long figure-eight, made a bed that was almost comfortable. A barley-sugar sweet, placed in the downhill cheek, spread an illusory warmth – bad for the teeth but good for morale. I certainly slept for some of the time.

After we’d listened to about a hundred thousand drips, the dripping darkness gave way to a dripping grey half-light. When you know you’re about to leave the bag and be even colder it seems less uncomfortable. A good shiver warms you up and then you can doze a little. Until a strange whirr and sudden rattle from overhead…

We were directly underneath the Mont Blanc cablecar. Fifty yards away in the grey air, well-fed people were passing through the sky in a warm plastic box. Their windows were steamed up: with any luck they couldn’t see us.

We packed our bags and scurried down the mountain. In the meadows below, the first of the new day’s climbers were heading for the Peigne. A pair with the patched-breeches look of the British were heading off towards the bottom of the 600m/2000ft terribly easy rockclimb…

PROBLEMS OF THE POLYBAG

Today we’ve upgraded the name to ‘Survival Bag’ but the price is relatively unchanged at between £5 and Free With This Month’s Issue. And there’s no doubt that these things do aid survival. Dumfriesshire, for example, has two extra inhabitants because of them. An elderly neighbour suffered a mild heart attack in the Enterkin Pass and lay for five hours in a snowstorm. A much younger one fell while descending into Glen Shiel, broke both ankles and jawbone, and nobody knew where he was except a friend who’d just that day emigrated to New Zealand. He lay in his bag for four days.

No piece of equipment does better in terms of lives saved per pound sterling, with the possible exception of bootlaces and other short lengths of string. But the survival bag means what it says. You wake up miserable, but alive.

Much of that misery is down to dampness. A medium-sized human, in the course of a night, emits about a pint of water. This pint (or half-litre, for a slightly smaller person who thinks in metric) condenses on the inside of the plastic. From there it gets into your hair, your clothes, your sleeping bag if you’re lucky enough to be in one. It gets in between the pages of this book: the later chapters will be largely concerned with that pint of water in the night.

The plastic sort of bag is like the western side of Scotland. It’s warmer, but also wetter.

This book is about misery that’s mixed in with pleasure, rather than taken straight: about self-indulgence rather than mere survival. However, all bivvybags do have a secondary function as survival aids, and it’s true that you can’t have much of either fun or suffering if you died the previous winter.

For pure survival, there are various items offered of lightweight plastic or so-called ‘space blanket’. These cost very little, weigh very little (about 100g/3oz) and they’re very little use.

That’s not the same as no use at all. After the London Marathon they gave us aluminised plastic wrappers with the sponsor’s logo. Thus we became, among the streaked concrete of Waterloo Embankment, a fluttering blue and silver throng as we consumed an other-worldly sports drink which itself tasted strongly aluminised. Space blanket claims to conserve 90 per cent of body heat. This is misleading. Heat is transferred by radiation, conduction and convection. When lying under a stone wall in a snowstorm, heat is lost by conduction (into the freezing ground below) and by convection (into the passing breeze above). Aluminised plastic reflects only radiant heat.

However, when strolling on the Embankment damp with sweat and wearing only your undies, the blue and silver wrapper is what you need over damp skimpy shorts and a Galloway Sheep tee-shirt.

This wrapper came free – I only had to run 26 miles to get it. And while it was of little use, it was also of little weight, which could be good value; so I took it on the Mountain Marathon. On these events a cooker is compulsory: so I also brought along some delicious savoury rice. Alas! When Glyn unwrapped the cooker it was of a purely formal sort – small paraffin blocks, a stove like a dead spider sculpted out of rust, and a foil tub for saucepan. The super-lightweight saucepan had been remarkable value: less than £2.50, with its first hot meal, plus beansprouts, included at no extra charge. However, it had been on several mountain marathons already and was no longer rice-tight.

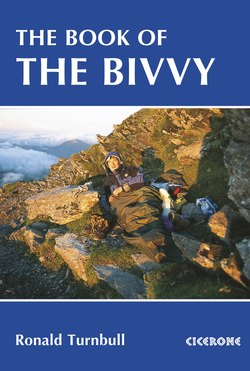

Ideal bivvybagging in the Picos de Europa, Spain

A saucepan liner cut from the London blanket turned out to be just the thing. It shrivelled above the soup-line, but held below. The moral? Anything’s useful, so just take whatever weighs least…

However, for serious survival (which means survival of snowstorms) you need a serious survival bag and this weighs 300g/10oz. This is thick enough to hold in heat as well as air, and stiff enough that the breeze won’t mould it against your body. The books say you should bite a hole in the corner of it to breathe through and then enter it head first. This makes sense: warm air rises and stays in the bag. However, I’ve never been quite desperate enough to bite a hole in something that cost me five shillings.

Two are not twice as warm as one in a bag, unless the bag’s a very big one. If the bag gets tight it compresses your clothing and the bits of you pressing against the outside get very cold indeed. There are, however, group bags: these are specifically designed for several people to get miserable in together.

PLASTIC BAG FOR PLEASURE PURPOSES

Some of us are too mean to buy a proper bivvybag, and some of us just like to see how much we can do without. I come into both categories. So here is the technique for primitive plastic travel.

If plastic bags get wet on the inside, the way to stay dry is to stay outside the bag. A foam mat is one of the things you probably didn’t bring, and the double layer of plastic underneath is insulation of a sort as well as groundsheet.

When it starts to rain, you can postpone the damp by moving under a nearby tree. When the rain starts to drip through the leaves, it’s just possible it may already have finished raining outside.

Otherwise, it’s time to get into the bag. Position it with the feet end slightly uphill. This means that condensation in the bag has a chance to trickle out the entrance. It also means that raindrops on the outside will drip off the doorway rather than trickling back inside. If you hold the entrance well open, air can get in and evaporate some of the condensation.

You wake up moist but warm. It’s the next night, the crawling back into a bag that’s already damp, that’s going to be really horrible. So the advice is not to do that next night, but to head off the hill to civilisation with its youth hostels and shops selling proper breathable bags.

However, it may quite possibly not rain at all. In which case you simply keep going until you run out of muesli. You lie late to let the sun take the dew off the plastic, amble down to the village whose lamps had lightened your night-time, and discover that, late though you lay, it’s still two hours too early for the shops.

POLYBAG FACTS

The basic polythene survival bag should cost between £5 and nothing at all – they may be given away free with outdoor magazines. A fertiliser sack does the same job more cheaply, though the bedtime reading printed on the outside is less entertaining. (The big-bag style is a good size: it’s important to wash out all traces of the previous contents as fertiliser damages the skin.)

The more the bag weighs the more effective it is – but the more it weighs, obviously. Eight to twelve ounces is a good balance between heaviness and uselessness. It should be long enough to be able to get right inside with boots on, and fold down the end so as to let the rain drip – this means 2m/7ft. If planned for two, it should be big enough to hang loose around them rather than stretched tight about their bodies.

The multi-person shelter does offer a significant weight saving, quite apart from the conviviality. The three/four person ‘Windblokka’ weighs 600g/1lb 4oz and is made of proofed ripstop nylon. It costs about £45. It’s designed for sitting up in rather than lying down and going to sleep.

One night under the moon in a plastic bag should persuade you that you want more nights under the moon, but in something other than damp plastic. Rawhide? Potato sacks? Stout Harris tweed? In the next chapter we’ll study various historic bivvybags even less accommodating than polythene.