Читать книгу Edible Mexican Garden - Rosalind Creasy - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеedible mexican gardens

My husband and I moved from the Boston area to Northern California in 1967. For a few days I was homesick and needed a reason to feel we had made the right decision. A former Bostonian friend had settled here a few years earlier and she invited us over for supper. Well, sir—she served tacos with homemade salsa. What a revelation! I’d never tasted anything so good—I was hooked. A few more Mexican meals and a trip to San Francisco and I knew I had found my spot in the sun.

Looking back, it’s amazing to me to see how, over the years, my day-to-day Yankee cooking has completely changed. Grilled cheese sandwiches somehow turned into quesadillas, my bread box always has tortillas, a comal (flat Mexican griddle) sits on the stove, ever ready to toast herbs or grill an onion, and chiles show up in so many of my meals that when members of my tender-tongued East Coast family come to visit, I have to change my whole repertoire.

My garden, too, reflects the south-of-the-border shift. Numerous trips to Mexico and much time spent in the Southwest, where Mexican culture dominates, not only changed many of the crops I grow but my garden aesthetic as well. As a landscape designer, I can design an English garden with the best of them—good enough, in fact, that on occasion I’ve had homesick Brits stand at the end of my walk and weep for home—but despite my English blood, my heart’s not in it. I keep coming back to an in-your-face, colorful garden style, all tangled with flowering vines and squash and filled with chiles and dahlias.

The gardens and recipes that I share with you in the following pages are from my years of experience, much of it from muddling through and still more learned from generous gardeners and cooks. I hope you find the information zestful, inspirational, and even more exciting in that the vegetables and herbs, and the cooking methods, are based in the Americas. I thoroughly enjoy Chinese and Italian vegetables, Southeast Asian herbs, and I glory in French cooking techniques, but over the years I find that growing and roasting great tomatoes and chiles, hominying corn, and stewing beans brings me truly home.

how to grow a mexican garden

Most of the vegetables in a Mexican garden are grown in a routine manner. The tomatoes, onions, hot peppers, and squash, for instance, are often the very same as or similar to those we usually grow in the United States.

Mexico is a huge country whose many climates range from tropical to temperate. Most gardeners in the United States can grow a good number of Mexico’s vegetables and herbs, but the nearer one lives to the Mexican border, the more options there will be for growing specific Mexican varieties.

Let’s start by surveying options open to gardeners in Canada and the northern U.S. They can grow numerous varieties of common vegetables used in Mexican cooking, such as tomatoes, Swiss chard, lettuce, radishes, white onions, and snap beans. They can also choose vegetables less common in the States but characteristic of Mexican cooking, such as many kinds of dry beans; some of the dent corns; jalapeños; purslane; tomatillos; round, light-colored zucchini-type squash, and the important herbs cilantro and epazote. Nurseries with a good selection of appropriate varieties for these short-season areas are Johnny’s Selected Seeds, Nichols Garden Seeds, Stokes Seeds, and Abundant Life Seed Foundation.

For more southerly gardeners, the array of authentic Mexican varieties is larger. Because the fall stays warm longer, they can grow day-length-sensitive varieties (varieties that don’t set fruit until the days get short in early fall) of winter squash and Mexican corn. There are also more chile options, plus the tender perennials, such as jícama and chayote, which need a long, warm growing season and a mild winter.

To obtain seeds of Mexican vegetables and herbs, consult the seed companies given in the Resources section of the book. Mexican seed companies are not cited, as they carry mostly commercial varieties of standard vegetables common in this country. Seeds of varieties favored by Mexican gardeners in the States can sometimes be purchased from seed racks in local Mexican grocery stores, especially in the spring. The rest of the varieties, including unusual Mexican herbs, are available from specialty mail-order nurseries or from local nurseries located in the Southwest.

In Mexico, most gardeners obtain their seeds from local purveyors, and if they are open-pollinated varieties, not hybrids, they keep the seeds from their plants from year to year.

Once you obtain your Mexican varieties, you may want to save your seeds too. See the sidebar entitled Saving Seeds for basic information. For specific information on saving the seeds of beans, corn, peppers, and tomatoes, see the “Encyclopedia of Mexican Vegetables.”

You will most probably get most of the seeds you want from the specialty seed companies listed in the Resources section but, if you visit Mexico, you can shop in the markets for an even larger selection. Most vegetable seeds in commercial packaging are OK to bring back home, except Mexican corn, which is confiscated at the border as illegal to bring into the United States. Another option is to visit a Mexican market near you to shop for seeds of pozole corn and dry beans. But when you grow these grocery store seeds out, be prepared to baby them for a few years. The folks I spoke with in the community garden in San José found it took two or three seasons to acclimatize the Mexican market corn, in particular, to their own gardens. Be aware, too, of the possibility that in wet, cold climates they may never acclimatize.

Seeds of Mexican varieties are sold in many Mexican markets in North America. They are generally available only in the spring.

Large blue buckets in a Yucatan market offers a variety of seeds and spices.

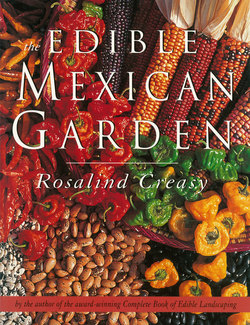

The harvest from one of my many Mexican gardens includes tomatoes, corn, chilis, and pumpkin.

[Saving Seeds]

I find saving seeds simple and satisfying process. The following general guidelines apply no matter what kind of seeds you are saving. See the “Encyclopedia of Mexican Vegetables” for more specific information on saving the seeds of beans, corn, peppers, squash, and tomatoes. In addition, everyone interested in seed saving will benefit from reading Seed to Seed, by Suzanne Ashworth. She gives detailed instructions on how to save seeds of all kinds of vegetables.

1. Save seed from open-pollinated (nonhybrid) plants only. Saving vegetable seeds from hybrids is wasted energy, as they will not come true—in other words, there’s no telling what you will get. Hybrids are created by crossing two vegetable variety parents; a gardener needs to know which two parents are crossed to create an identical variety. For proprietary reasons, seed companies keep that information to themselves. They do however, label hybrids and Fl hybrids (first-generation hybrids) on their seed packages, so you know which are hybrids and which are open-pollinated.

2. When you are saving seeds to perpetuate a variety, you need to take steps to prevent cross-pollination. With some plants, such as beans, which are primarily self-pollinated, cross-pollination problems are few. For others, more protection is needed. Get to know the vegetable families, as members of the same family often cross-pollinate. A list of vegetable families is included in Appendix A with the information on crop rotation; see page 94.

3. Do not save seeds of diseased plants. Save only the finest fruits from the best plants of your favorite varieties. You need to learn to recognize diseases because some (particularly viruses) are transmitted in seeds.

4. Label your seed rows and seed containers; your memory will play tricks on you.

5. Never plant all your seeds at once, lest the elements wipe them out.

6. To maintain a strong gene pool, select seeds from a number of plants, not just one or two. (This does not apply to self-pollinating varieties.)

7. Only mature, ripe seeds are viable. Learn what such seeds look like for all your vegetables.

To get you started with your own Mexican garden, in the next section I rhapsodize about my own Mexican gardens, both full size and in containers, and Kit Anderson shares her Vermont Mexican garden as well. For specific information on each vegetable, see the “Encyclopedia of Mexican Vegetables.”

Chayote, white onions, tomatoes, and chilis are the basis for many a great Mexican meal.

creasy mexican gardens

For three decades, I have been an active vegetable gardener, much of it professionally. In the first decade, I mastered the basics like sweet corn, tomatoes, snap beans and was ready for something more exotic. Inspired by my travels, I decided to try growing ethnic vegetables of all types; from Mexican amaranths and Italian radicchios to Asian pac chois, tucking them in among their more prosaic cousins. Eventually, armed with all my new knowledge. I started a large garden cookbook and decided to grow a number of ethnic theme gardens for the book, including a Mexican one. I needed to grow out many unusual vegetables and herbs to develop my recipes. Also, I wanted to see how prototypical ethnic gardens went together and how well they fit into a standard American garden.

My first Mexican garden was planted in the corner of my backyard nearly fifteen years ago. It included all sorts of vegetables and herbs I had never seen before, much less grown, including epazote, huauzontlí, grain amaranths, and wild chiles, plus numerous unusual varieties of familiar vegetables, including grinding corns, tomatoes, peppers, lima beans, and sunflowers and pumpkins, for their seeds.

I not only wanted the vegetables to be Mexican but, as a landscape designer and photographer, I wanted the garden to give the feel of Mexican home gardens I knew. The ones I was familiar with were filled with exuberance, joy, and colorful flowers—and, in most of Mexico, planted in layers, with vegetables, herbs, and flowers among and under fruiting and flowering trees.

With these design goals in mind, I added a number of flowers I associate with Mexico, namely, tithonia (also called Mexican sunflower), Mexican sage (Salvia leucantha) and two south-of-the-border favorites, marigolds and nasturtiums. Because Mexican peppers, tomatoes, and tomatillos need a long growing season, I seeded them in the house under lights, starting with the peppers in February. A month later, I started the tomatoes, and a few weeks after that, the tomatillos. Once they became mature enough, I moved them outside to my cold frame.

I must say, I mastered the exuberance component! The garden spilled out of its boundaries, thanks in part to my great organic soil, which caused the corn to grow to 14 feet, the amaranths to tower over the tomatoes, and the tomatillos to sprawl over everything. The joy was evident, too; it was so much fun to explore a whole new garden culture and cuisine. Tacos, refried beans, and hominy from red dent corn was great fun. The bright colors, though, were definitely missing. Even with the addition of impatiens and gloriosa daisies at midsummer, I thought the garden still a bit too pale.

A few years later, I set out to grow another Mexican garden, this time with lots of color! And I really went for it this time. I filled up the whole front yard. Bougainvilleas, dahlias, cannas, morning glories, marigolds, nasturtiums, and zinnias were sprinkled among the vegetable beds and along the front path. For a little more oomph, I had a trellis painted with primary colors and topped with a sun face created by my artist friend, Marcy Hawthorne.

North American gardeners need to start a number of Mexican specialties from seeds in order to get a jump on the season. Appendix A gives specific information for starting seeds inside. I use a cold frame as intermediate housing for my tomatillos, jícama, chilis, tomatoes, and Mexican herbs I’ve started inside.

As the weather warms, I gradually leave the lid open longer. About fifteen years ago, I planted my first Mexican garden and filled it with corn, pumpkins, tomatillos, lima beans, and sunflowers It was a greatly productive garden—but didn’t have enough color for my taste.

Well, let me tell you, it worked. This garden stopped joggers in their tracks. Here among the suburban lawns and polite evergreens was an in-your-face-garden so filled with color and flowers you could hardly see all the veggies. I’d found the formula!

Since that time, I’ve created numerous Mexican gardens, including two minigardens I filled with Mexican herbs and chiles in colorful containers and a large front garden of big running squash and bush beans with a front border filled with sunflowers, scarlet runner beans, amaranths, and giant Mexican corn. This garden featured all plants from the New World and it was sensational.

A few years after my first Mexican garden, I planned one for the front yard. This time I put in a bright-colored arbor and added lots of bright flowers like dahlias, sunflowers, marigolds, nasturtiums, and cannas. The large beds were filled with chilis, corn, pumpkins, squash, and tomatoes as well as epazote, Mexican tarragon, and Mexican oregano. This iteration was so splashy it stopped traffic!

My last Mexican garden was enclosed by a stucco wall and included a small patio of random paving stones interlaced with broken blue tiles. It was planted early, as soon as the weather warmed up in early April, with the tomatillo ‘Toma Verde,’ some Mexican chiles—poblano, jalapeño, serrano, ‘Habañero,’ ‘Mulato,’ and ‘Chili de Arbol’—and ‘Beefsteak’ and ‘Costoluco Genovese’ tomatoes, all of which we had started from seeds and hardened off in the cold frame. We filled some of the room between the plants with ‘Iceberg’ lettuce and cilantro, knowing these would be long gone before the other plants filled out. Unfortunately, the weather got unusually cold; in fact, we had a record-cold April and May and needed to put red plastic mulch down around the tomatoes and chiles to keep them going. We delayed more planting as well. Consequently, the ‘Golden Bantam’ corn, ‘Peruano’ dry beans, chayote, jícama, watermelon, ‘Grey Zucchini,’ and grain amaranth, all of which need very warm conditions, didn’t go in until early June. The warmth also brought on the purslane (pigweed), which we usually pull out right away. This time, though, we let it grow and fill out until it was big enough to harvest. What a revelation. I’d been pulling it out for years. It tasted so good in some of our recipes I’m sure I will keep some of it around indefinitely.

A harvest from one of my latest Mexican garden includes white onions, lima beans, tomatoes, chard, corn, beans, and lots of chilis.

My most recent Mexican garden has many containers filled with Mexican herbs and chilis. The corn and watermelons fill the back beds; tomatoes and peppers in the middle and driveway beds. Jicama rambles over the low front fence and a chayote wanders around behind the corn.

To fill out the garden, I sent away for Mexican specialties, including epazote, Mexican tarragon, cumin, huauzontlí, and chía, and grew most of them in containers. For bright colors, I planted lots of zinnias, petunias, and marigolds in cheery containers. I especially liked the hot pink and orange plastic buckets I had purchased in the Tijuana produce market.

I’m sure I will continue to create new Mexican gardens for years to come. They are so cheerful and exuberant, the neighbors love to look at them, and eating their bounty is one of our favorite family feasts.

[Flowers in the Mexican Garden]

Flowers are integral to a Mexican garden and while they add lots of life and color, as an added benefit they attract hundreds of beneficial insects to help protect against pests. When I started growing Mexican-style gardens I put in too few flowers and the gardens never looked quite right, now I include many. I don’t always stick to flowers from Mexico, using plants like gomphrena and impatiens, but I find that the varieties from that part of the world look the most at home.

Many of our most popular flowers originated in Mexico including: marigolds, zinnias, nasturtiums, morning glories, cosmos, tithonias, sunflowers, verbenas, and many different sages. Bougainvillea and cannas are two other plants, native to tropical South America, that look particularly at home in a Mexican garden.

When I choose my flower varieties I lean toward bright primary colors and include lots of orange and hot pinks. I plan out where the flowers go by determining their final height at maturity. That means I usually put the tall sunflower varieties and tithonias in the back of the border in among or in front of the corn and tall amaranths (choosing the north side of the garden so they won’t shade the other plants). I use the full-size cosmos, tall zinnias and marigolds, and most sages in the middle of the border, often among tomatoes and tomatillos; and I interplant the dwarf marigolds and verbena among the peppers and herbs. Dwarf nasturtiums I use for the borders of beds and in containers, and the large vining ones I use to cascade out of planter boxes. Morning glories are great on arbors, sometimes interplanted with chayotes or jícama, and I like to cascade them over a fence.

A garden full of bright-colored flowers speaks to Mexico. As a bonus, it also gives you armloads of flowers to bring in the house for bouquets.

mini mexican herb gardens

I have many colorful containers of Mexican herbs decorating my garden, even though I live in a mild climate, USDA Zone 9. Part of the reason I plant them is that they look great and I can keep them near the kitchen, but mostly I grow them because my climate is too cold to overwinter most of them. My solution is to grow the tenderest of them in containers and then either put them in my cold frame or bring them inside to my windowsill.

The Mexican herbs I’ve tried in containers are: cilantro, culantro, epazote, Mexican oregano, hoja santa, spearmint, and Mexican tarragon.

I was not always successful at growing plants in containers; in fact, at first I lost most of them before winter even set in. Through trial and error, I’ve found what I call the secrets for growing herbs in containers:

1. I use only soil mixes formulated for containers. Garden soil drains poorly and pulls away from the sides of the container, allowing most of the water to run out, and it often is filled with weed seeds. Straight compost is too fine and plants will drown.

2. Containers must have drainage holes in the bottom to prevent the plant from drowning. At planting time, I cover the holes with a piece of window screening or small square of weed cloth to keep dirt in and slugs out. (New evidence indicates that gravel or pottery shards in the bottom actually interfere with drainage.)

One of my favorite patio designs included a chair from Mexico designed by Roberto Matias from Oaxaca. Around it I cluster containers of ‘Super Chile,' a yellow ornamental pepper, a container of Mexican oregano, and a pepino plant native to South America. A tall chiltepín chili plant was very productive and by the holidays was covered with red fruits. I added marigolds, sunflowers, and some blue statice to give color.

3. I now use only containers large enough to provide generously for the plant’s root system and hold enough soil to avoid constant watering. I find most herbs grow best in large containers 18 inches, or more, in diameter. My southern friends report that in their climate, large containers are mandatory because the roots on the south side of small pots bake in the hot sun.

4. After years of pale plants, I found I need to fertilize frequently and evenly. For me, biweekly doses of fish emulsion work well, as does granulated fish meal renewed every five or six weeks.

5. I find the most difficult aspect of container growing is to maintain the correct moisture in the soil. Cilantro and mint suffer if allowed to dry out, but the Mexican oregano, Lippia graveolens, is drought tolerant and succumbs to root rot when overwatered. When I learned how to water properly, I was on the road to success.

6. When I bring the herbs in for the winter, I give them a half day of shade for a few weeks to prepare them for darker conditions. Before bringing them in, I wash the foliage well. I then locate them in a bright, sunlit spot away from heater vents. I water them less indoors than when they are actively growing in the garden. I keep them barely moist and I fertilize only when the days get longer in the spring.

A further note on watering: All gardeners need to learn to water container plants properly. Even in rainy climates, hand watering containers is usually a necessity, as little rain penetrates the umbrella of foliage covering a pot. I find that it is most helpful to water the container at least twice—the first time to moisten the soil (I think of it as moistening a dry sponge.) and the rest to actually wet it. To prevent the opposite problem, overwatering, I test the soil moisture content with my finger before watering.

Watering container-grown herbs is critical for all gardeners, but it’s of particular importance for those of us who live in arid climates. After years of parched-looking plants, I finally installed a drip system. What a difference! I use Antelco’s emitters, called shrubblers (available from plumbing-supply stores and via mail order from The Urban Farmer Store, listed in the Resources section on page 104), as they are tailored so each container on the system can have the exact amount of water it needs. My drip system is connected to an automatic timer and scheduled to water every night for four minutes from spring through fall.

I enjoy planting Mexican herbs in colorful containers It’s also an advantage when growing the tender varieties like culantro and Lippia graveolens as they are more readily brought inside when the weather gets cold.

Here, in the blue pot, is Mexican tarragon; in the purple, an ornamental chili; next, a large pot of cilantro; and in the red pot, a Mexican basil. My patio a number of years ago was filled with herbs and chilis The chili plants included, from the left, a tall ‘Chili d’Arbol,’ a serrano, and a shorter chilipiquín all grown in a large wooden planter box. Another chilipiquín grows in a large blue pot.

interveiw

the Anderson garden

That I grew a Mexican garden in California wouldn’t be big news to most gardeners. But I knew most Mexican vegetables and herbs could be grown in northern gardens as well, and I needed a demonstration garden to prove it. Vermont sounded convincingly northern, so I approached Kit Anderson, my good friend and, at the time, managing editor of one of the country’s finest gardening magazines, National Gardening, in Burlington, Vermont. Kit and I had worked on many projects together and I knew of her great interest in both Mexico and, of course, gardening.

We did some initial planning together, Kit did the ordering and the labor, and, after the harvest, I asked her to write a detailed account of her Vermont Mexican garden. It tickled me to invite one of the country’s premier gardening writers to contribute an essay to this book. Kit loved the idea. Here’s what she wrote:

“The eighteen-inch-tall statue of the Mexican corn god must have suspected something when I wrapped him in a blanket for the trip back from his native land to icy Vermont. Little did he know, but he had his work cut out for him. After all, our New England climate is not exactly suited for tropical crops. That’s why we started planning the garden by crossing off those vegetables that wouldn’t mature in a brief season. It meant we had to leave out chayote, jícama, and some of the southwestern flour corns and day-length-sensitive chiles. But we still had plenty to choose from: many chile peppers, tomatillos, bunching onions, cilantro, Mexican pinto beans and corn for drying, plus such necessities as tomatoes and squash.

“Growing heat-loving crops in Vermont isn’t as absurd as it sounds. We grow fine peppers and tomatoes just about any year, and I’ve even had okra produce some summers. I live in a relatively warm part of the state, the Champlain Valley, which extends all along the western border and is almost at sea level. Our frost-free season often lasts close to 150 days, compared to the 90 to 120 usual in the mountains to the east. And it gets hot in midsummer.

“Nevertheless, we had to choose varieties carefully. After scanning a number of catalogs, we found a number of suitable varieties. Then came the design of the garden. I wanted it to have a Mexican feel to it, not be simply rows of crops that happened to be from that part of the world. Tropical gardens tend to be much less organized looking than the typical American garden. They’re liable to consist of fruit trees, flowers, vegetables, and herbs, all growing in apparent disorder in the area around the house. Where sunshine is abundant, layered gardens make sense, with some crops growing in the shade of others, but without avocado trees and tamarind for shade, and with crops that would need all the sunshine they could get, our Vermont garden wasn’t going to be layered—that approach just wouldn’t work.

“I compromised. The plan became a puzzle, with irregularly shaped beds each containing a combination of vegetables and flowers of different heights, and all planned so that sunshine would get everywhere. At the center, of course, would be the corn god.

“The next major challenge was the heavy clay soil in my garden. Even after adding a lot of organic matter, I can only harvest carrots after a heavy rain (and then I bring up huge globs of soil along with the roots.). Combine that with a cool, wet spring and you have about the worst possible conditions for heat-loving crops.

“Fortunately, we had a wonderful, early, relatively rain-free spring that year, so I was able to get in and till in April and incorporate much composted manure. I still had a long wait before I could plant most of the crops. Our average last frost date here is May 15, but peppers hate to be cold. It does no good to set them out early; they’ll only be stunted. In late April, I started cilantro, tomatillos, and ‘Lemon Gem’ marigolds in pots in my cold frame (a simple affair made of plastic).

Kit Anderson’s harvest from her Vemont Mexican garden.

“Encouraged by the warm weather, I set my pepper plants outside, let the young plants harden off (acclimatize outside) for a few days, and then put them out in the garden on about May 7, with individual wax-paper hot caps (little individual shelters) to protect them. The poor things needed all the help they could get because the weather turned cool and rainy for several weeks. Finally it warmed up again and I uncovered the peppers, as they were pushing up the hot caps. That night a ferocious storm blew in. My children watched in amazement as I screamed at the hail that was pounding the kitchen. But even that storm didn’t faze those peppers. Except for a few ragged leaves, they looked just fine the next day.

“The little cilantro plants and the tomatillos went in next, along with a few cilantro seeds, a row of bunching onion seeds, and a few rows of pinto beans. By May 31, everything was planted, with the corn god occupying a place of honor in the center of the garden.

“To keep down weeds, I mulched with grass clippings around everything. The paths were covered first with newspapers, at least sixteen pages thick, then with shredded bark. Finally, I set up a combination sprinkler and drip system. This last step proved unnecessary, though, for we headed into the coolest, wettest summer I’ve ever experienced in Vermont. Eggplants everywhere languished. Tomatoes ripened late. Squash, even zucchini, produced poorly. We had great lettuce for tacos but not much else to go with it. It seemed impossible that the Mexican garden would make it, but it plugged right along. The peppers started bearing fruit by late July and kept up through September. The corn grew (slowly) and matured beautiful ears. The cilantro, especially the batch started early, made a lot of greens before going to seed. I cut it all back once, froze the leaves, and then let the plants go. The plants allowed to mature produced seeds and from these I got another harvest of leaves later in the season. The beans were fine until September; then I had to take them into the barn to dry because they started to sprout during a few late rains. The tomatillos grew like mad, overwhelming everything near them, getting much larger than I’d planned. The tomatillo is a low-growing, hulking sort of plant that needs its own space. The amaranth I’d carefully planned as a backdrop—with the supposedly smaller yellow strain in front and the red in back—did not cooperate; the yellow turned out to be much more vigorous, dwarfing the dramatic red plants, which just peeked through from behind.

“The garden was at its best in late July, although the marigolds had been slow to begin flowering, so things weren’t as colorful as I’d hoped they’d be. Tithonia, the Mexican sunflower, was a disappointment, too; it had lots of green foliage but flowered only late in the season.

“When corn harvest time came, my son and I had a wonderful time picking the ears and pulling off husks to reveal the richly colored kernels, everything from blue to red and yellow. I displayed some of the ears for months in a basket in our kitchen.

“Unfortunately, I never had time to develop great gourmet recipes with all these crops. We did feast on lots of tacos with chopped fresh tomatoes and cilantro and had salsas made of tomatillos, chiles, and green onions. I discovered I liked cilantro and have also used the frozen leaves for soups and in esquite, a corn dish sold on street corners that I had learned to love in Mexico.”

Despite the problems, Kit’s enthusiasm for her Mexican garden was constant and infectious. When I visited in July, the garden was beautiful and I was reassured to see everything doing so well. Even though I’d heard garden experts talk about growing chile peppers, cilantro, and tomatillos in northern climates, I found it much more convincing to see and touch the thriving plants myself.

Except for the watermelon, all the plants shown here—including grinding corns, summer and winter squash, and many types of peppers—have all evolved from plants native to Mexico and Central America. Though native to Africa, watermelons are very popular in Mexico.