Читать книгу Edible Asian Garden - Rosalind Creasy - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеthe edible

asian

garden

Over twenty years ago, in preparing for a trip to Hong Kong, I wanted to become proficient at eating with chopsticks so as not to embarrass myself. I practiced by using them to pick up dry macaroni until I thought I had acquired some skill. For our first dinner in Hong Kong, my husband and I arrived at the restaurant starving. To begin the meal, the waiter placed a bowl of shiny, round Spanish peanuts in the middle of the table. Ah, food! I glanced around and discovered that the other diners were eating these nuts with their smooth, tapered chopsticks. Gamely, I plunged in—and onto the table went my peanut. Discreetly, I tried again and again in vain. Finally, I snared a nut—but squeezed too hard and, just as the waiter looked our way, “spronged” it against the wall! So much for saving face!

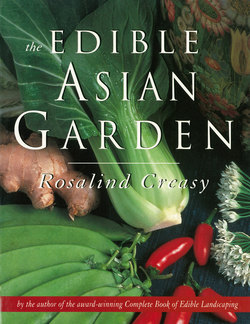

Pac choi, ginger, snow peas, hot peppers, and Oriental chives are most beloved in much of Asia.

Chopsticks aside, we had a wonderful time eating our way through Hong Kong. We dined on familiar stir-fries made with baby corn and pac choi, eggplants with garlic sauce, and asparagus with shrimp. But we also tried the unfamiliar—eels, sea cucumbers, and all sorts of vegetables, mushrooms, and ingredients we couldn’t identify. Regardless of what dish we ordered, the seafood and vegetables were always fresh and the preparation impeccable, and we thought the food, with few exceptions, the best we had ever eaten in our lives. I decided that if I were shipwrecked on an island and could have only one type of food for the rest of my life, this is what it would be—not my own native fare, not even French cuisine, but the food of the island of Hong Kong.

In fact, although we shopped, visited museums, and wandered around the waterfront, food in all its forms became our main interest in Hong Kong. We spent hours selecting restaurants from among the Japanese, Korean, and Chinese choices, and more hours choosing our food. We made numerous visits to the old part of the city, where herb stores abound and produce markets line the sidewalk. There we saw people walking down the street carrying water-filled plastic bags containing swimming fish, and string bags bulging with fresh bamboo shoots and unusual mushrooms. And we saw all sorts of fresh greens—I couldn’t get over the variety. Everywhere I looked were green, leafy vegetables I’d never seen before. Much to the shopkeepers’ amusement (probably because we looked so puzzled as we hovered over the bins), we’d buy all sorts of unfamiliar fruits and vegetables and bring them back to our hotel to taste and photograph them. After laying out a towel to provide a neutral background, I’d set down a spoon to give the picture scale, lay out the edibles, and then photograph them one by one. Then, with the produce well documented, we’d taste everything and make notes.

A typical vegetable garden in Japan is planted with onions, chives, and many different greens. As in much of Asia, the beds are in straight rows and raised above grade.

That long-ago trip to Hong Kong opened my eyes to a whole new world of vegetables and cooking. It became obvious to me that the main focus of Chinese cuisine was on vegetables and that the varieties far exceeded my limited experience. It also became clear that the Chinese food I had eaten in restaurants at home only hinted at the heart of that cuisine. Because fresh Asian vegetables are the cornerstone of Chinese cooking, because restaurants in the United States generally can’t obtain them, and, further, because the American audience is fixated on meat, what I had come across in the States was only a limited sample of Chinese cooking as a whole.

Once home, I began to research Asian cooking in earnest. I visited the community gardens of nearby Southeast Asian neighborhoods and began to frequent Japanese and Thai restaurants to learn about tempura and curries. I sought out Chinese restaurants that prepared pea shoots and gai lon and a Japanese market that featured a whole section of Asian pickles with a tasting bar. As the years went by, accumulating information became much easier as northern California evolved into America’s newest cultural melting pot, one brimming with folks from the Pacific Rim. Now I had Asian neighbors to share food and garden information with, huge new local grocery stores catering to a Japanese and Chinese clientele, and neighborhood markets devoted to East Indians and Southeast Asians—and mine to explore.

By now I’ve not only identified all the produce I collected in Hong Kong, I’ve grown and cooked with nearly all of the vegetables and herbs Asia has to offer. But I am but one gardener-cook, and Asian vegetables and food is a vast subject. I needed many other views. Fortunately, I have been able to spend hours with Asian chefs, including Ken Hom and Barbara Tropp, tour seed company trial plots, and work all over North America with home gardeners and cooks interested in Asian vegetables. One gardener in particular, David Cunningham, who was staff horticulturist at the Vermont Bean Seed Company, even grew an Asian demonstration garden for me to share with you.

Throughout this book, I give information on the vegetables and herbs of Japan, India, Korea, Southeast Asia, and the Philippines. You will soon see, however, that I have concentrated on the vegetables and cooking methods of the Chinese, as they cook with the greatest variety of vegetables and the seeds of their plants are the easiest of all Asian varieties for gardeners to obtain. Further, of all Oriental cooking styles, that of the Chinese is most accessible to Western cooks and uses the fewest unfamiliar techniques.

Before you lies a whole new range of vegetables and herbs: Shanghai flat cabbages, Chinese chives, Japanese mitsuba, and Thai basil. As a gardener and cook, you might well be embarking on a lifetime of exploration, and it’s none too soon to start!

Peter Chan’s garden (opposite) is filled with Asian vegetables like pac choi and Asian squash, which in this case, because of cool Oregon summers, was planted in a tall planter box for extra warmth.

Farmer’s markets around the country are often great places to purchase and learn more about Asian vegetables. Here at the Mt. View, California farmer’s market are displays of bitter melon vines, water spinach, pac chois, long beans, and Asian eggplants.

how to grow an asian garden

Many of the vegetables and herbs used in Asia are familiar to Westerners. In fact, we enjoy many cucumbers and winter squash varieties without even being aware that they come from Japanese breeding programs. Many of the so-called English cucumbers are examples. When you peruse seed catalogs looking for varieties, keep an eye out for sweet, “burpless” cucumbers such as ‘Suyo Long’ and ‘Orient Express’ and for dense, flavorful, nonstringy, sweet winter squash varieties such as ‘Sweet Dumpling,’ ‘Red Kuri,’ and ‘Green Hokkaido.’ Asian gardeners also breed and grow such familiar vegetables as eggplants, carrots, and turnips. Basic information on some of these vegetables is given in “The Encyclopedia of Asian Vegetables.” Still, many Asian vegetables and herbs are unfamiliar to Western cooks and gardeners and it is on these that I concentrate most of my attention.

In much of Asia, land for cultivation is scarce and highly revered. Unlike many Western gardeners and farmers, who often mine the organic matter from the soil and then rely on chemical fertilizers, out of necessity, Eastern gardeners have recycled nutrients for eons. In fact, they are responsible for developing some of the techniques gardeners refer to collectively as intensive gardening.

When I started gardening in the 1960s, sterile, flat soils supplemented with chemical fertilizers and broad-spectrum pesticides were de rigueur. Trained as an environmentalist and a horticulturist, I questioned these techniques, and by the late 1970s I was a strong advocate of recycling, composting, raised beds, and organic fertilizers and pest controls. Always on the lookout for others of like mind, in the early 1980s I visited with Peter Chan, who gardened at that time in Portland, Oregon. Peter had long been a proponent of an intensive style of vegetable gardening, which he covered in detail in his book Better Vegetable Gardens the Chinese Way. Raised in China and trained in agriculture there, Peter wrote of cultural techniques used in China for centuries, including the raised-bed system that promotes good drainage, supplementing soil with organic matter, and composting. Comparing notes with Peter, I found I had instinctively been using numerous time-proven Chinese gardening techniques.

The gardens described in this book, and many of the gardening techniques described in the Appendices, were primarily grown in the Chinese manner—methods now accepted by many modern gardeners worldwide. In addition, I include information on growing greens in what is called the cut-and-come-again method. (See the discussion of my stir-fry garden on page 11 for details.) While not widely practiced in Asia, this method fits right in, as it takes advantage of small spaces.

When I first became interested in Asian vegetables, I was most drawn to Chinese varieties and cooking methods, and I still find them a great place to start for beginners and for gardeners in cooler climates. But in the last decade the gardens and cooking of Southeast Asia have caught my fancy and I now also experiment with Thai chiles and basils, Vietnamese coriander, lemon grass, and cilantro, among others. Most of these plants are perennials, and while finally becoming more available in nurseries, as they are native to warm climates they are less hardy; most gardeners, including myself, must bring them in over the winter. While they can be a challenge, they are well worth the effort.

The following sections detail both cool-season and warm-season gardens. Most are in my northern California USDA Zone 9 garden, but David Cunningham’s Vermont garden offers time-proven techniques for growing in a colder climate. In “The Encyclopedia of Asian Vegetables,” I give copious information on growing all the vegetables in the coldest climates as well as in the semitropical regions, where some of the specialties of Southeast Asia will do especially well. For detailed soil preparation, composting, crop rotation, starting from seeds, transplanting, maintenance, and pest-control information, see Appendices A and B.

A typical Asian harvest (right) includes Asian eggplants, pac choi, bitter melon, and shallots.

Creasy asian gardens

I live in an unusually good climate for growing cool-season (fall, winter, and spring) vegetables, but it is only so-so for warm-season ones. My garden is in USDA Zone 9, about twenty-five miles from the Pacific Ocean—even less from the San Francisco Bay. The marine influence means winter temperatures seldom sink into the low twenties, with daytime averaging in the fifties. In summer, often the fog doesn’t burn off until midmorning, daytime temperature averages in the high seventies, and most nights are in the high fifties. The moderate winter temperatures are perfect for peas, carrots, root vegetables, greens, and all members of the cabbage family, but summer temperatures are borderline for peppers, eggplants, yard-long beans, and some semitropical herbs.

Over the years, I’ve experimented with hundreds of Asian varieties of vegetables, growing them in small beds by themselves or tucking individual plants in among my lettuces, beans, and tomatoes, but I became inspired to grow a whole garden of Asian vegetables over a twelve-month period, all done specifically for this book.

To give the gardens the feel of Asia, I used bamboo for fencing and trellises and selected rice straw for the paths. The plants were grown in straight rows, which is typical of most Asian gardens, and the beds were raised and formed into geometric patterns. I moved my decades-old Japanese maple into the garden for a focal point, and Edith Shoor, an accomplished ceramist, provided some of her Asian-style pottery for decorative touches here and there. The process was great fun and it entirely transformed my front-yard vegetable garden.

I have incredibly good soil. Of course I should. After twenty years of adding organic mulches and lots of loving care—such as never walking on the beds, planting cover crops, and adding chicken manure from my “ladies” every year—I can dig a hole using only my bare hands.

Shown in the photo to the right are some typical Asian ingredients: Winter melon; Southeast Asian green and white and yellow round, and long purple eggplants; lemon grass; luffa; white bitter melons; and bitter melon vines. One of many Creasy cool-season, frontyard gardens is shown on the opposite page, above. Snow peas are trained on string tepees and Shanghai pac choi and tatsai are growing in the front bed. The harvest from the garden (opposite, below) includes snow peas, Japanese red mustard, leek flowers leaves, and pac chois.

The Creasy Cool-Season Vegetable Garden

In late August, my crew and I started seeds of pac choi, mustards, and golden celery in flats to transplant into the garden. In late September, the seeds of snow and pea shoot peas, coriander, fava beans, daikons, Japanese varieties of carrots and spinach, shungiku greens, and bunching onions were all planted directly in the garden. We had good germination on all of the plants, but the slugs went after the coriander seedlings and they needed replanting three times. All went well until January, when we had seven nights in a row that went down to 23°F. Now that’s real cold for us Californians and the fava beans burned back to the ground and some of the half-grown pea plants were so weakened we took them out. The cold weather continued into April (March was the coldest on record, with few days climbing out of the forties) and the whole garden was almost a month behind. But it’s amazing how resilient cool-season plants are. The fava beans completely recovered and, in fact, produced six or seven stalks instead of the usual three; by early March, the mustards, carrots, onions, daikons, and many greens had revived from their sad-looking state and were producing beautifully. Most of the mustards and the pac choi were played out and the bunching onions were gone by midMarch. Baby turnips, different greens, and new onions were planted to fill in the beds before the summer crops could be planted.

Another Creasy cool-season Asian gardenis shown opposite, above. In November, the beds in my USDA Zone 9 garden are filled with seedlings of mustards, daikons, pac chois, and Japanese carrots ready for thinning. A few months later (opposite, below), the beds are ready for harvesting. The cool-season garden in May is pictured on this page. The fava beans on the left are starting to produce, the snow peas and spinach are in full production, the mizuna is in full bloom and attracting beneficial insects by the drove; and a second planting of greens is ready for harvest.

Stir-fries with gai lon, snow peas, and carrots, and dumpling soups with pac choi and mustards were favorite dishes in my house. I had never made them with pea shoots or with gai lon before, and they are great. New to me were the daikons, shungiku greens, and burdock. As I don’t especially enjoy radishes, I was pleasantly surprised to experience their mild, almost sweet taste in a pork soup my neighbor, Helen Chang, taught me to make, and I enjoyed the daikon pickles made with carrots as well. Helen also showed me how to cook fava beans in the Chinese manner by stir-frying them with garlic and letting visitors peel their own beans as a snack, making them easy to prepare. The shungiku greens were lovely made with a sesame dressing and their flowers created a smoky, mild tea. The burdock was great in a beef roll; I plan to grow it again next year to explore more recipes that feature it. In all, the garden expanded my Asian repertoire. Next winter, I am sure to plant more daikons and fava beans. This garden almost made winter so great I will look forward to the cool temperatures. Well, maybe that’s an overstatement.

Plants in the Cool-Season

Creasy Asian Garden

Bunching onion: ‘Evergreen’

Burdock: ‘Takinogawa’

Carrot: ‘Japanese Kuroda,’ ‘Tokita’s Scarlet’

Celery: ‘Chinese Golden’

Chinese chives: ‘Chinese Leek Flower’

Chinese kale: ‘Blue Star,’ ‘Green Delight’

Coriander: ‘Slo-Bolt’

Daikon: ‘Mino Early,’ ‘Red Meat’

Gai lon

Japanese onion: ‘Kuronobori’

Mizuna

Mustard: ‘China Takana,’ ‘Osaka Purple’

Mustard spinach: ‘Komotsuna’

Pac choi: ‘Mei Qing,’ Tatsoi

Peas: ‘Snow Pea Shoots’

Shungiku: ‘Round Leaf

Snow peas: ‘Sopporo Express’

Spinach: ‘Tamina Asian’

Turnips: ‘Market Express’

The Pleasures of a Stir-fry Garden

In the early 1960s, if you were interested in cooking, Cambridge, Massachusetts was a great place to be. Two of this country’s doyennes of cuisine held court there: Julia Child and Joyce Chen. Both were filming television shows, and Joyce, author of The Joyce Chen Cook Book, was teaching Chinese cooking classes at her restaurant. Living there, I caught the bug and I learned everything—from folding wontons to making béarnaise sauce. From Joyce, I learned one of the most valuable cooking skills you can acquire—how to stir-fry—which became especially pertinent years later, when I became a demon vegetable gardener. Vegetables are the stars of most stir-fries. As a bonus, the recipes are easily varied; one tablespoon of peas or a cup, it seldom matters.

Many years later, after having moved to California, the impetus for creating a specific stir-fry garden was set in motion. I shared a small, sunny part of my garden with a young neighbor, Sandra Chang. As fall approached, it occurred to us, as her mother, Helen, and I used much of my harvest for stir-frying, and so many Asian vegetables grow best in cool weather, that a garden of all stir-fry vegetables would be fun.

Together we chose ‘Joi Choi,’ a full-size, vigorous pac choi; ‘Dwarf Gray’ snow peas and ‘Sugar Snap’ peas; spinach; tatsoi and ‘Mei Qing’ dwarf pac choi; onions; carrots; cilantro; shungiku; ‘Shogun’ broccoli, and a stir-fry mix from Shepherd’s Garden Seeds containing many different mustards and pac choi. (Winters here seldom go below 28°F; gardeners in cold winter areas would do best to plant these vegetables in early spring.) I planted no Chinese cabbages, however; mine always become infested with army worms and root maggots.

We started seeds of broccoli and pac choi in August in a flat and direct-seeded the peas in the garden in September. My garden beds are rich with organic matter, so all we added was blood meal before planting. We had extra seeds of many of the greens, so we planted them in containers and grew them on my back retaining wall to see how well they would do. (They grew very well—we fertilized them with fish emulsion every four weeks.) The Shepherd stir-fry mix we planted in a little square of soil, about three by three feet, using the cut-and-come-again method. We prepared the soil well and broadcast the seeds like grass seeds, covered them lightly with soil, firmed them in place, and watered them in. We kept the bed moist and had great germination. We didn’t thin it, and the seedlings grew problem free—except for occasional slugs, which I controlled by making a few nighttime forays with a flashlight. The vegetables were ready for harvesting at about three inches tall. Using scissors, we snipped our way across the bed an inch above the ground, harvesting as much as we needed at a time. We found these baby greens great for salads and added at the last minute to stir-fries. We fertilized the bed with fish emulsion after harvesting and were able to harvest the greens a second time a month later.

A close up (opposite) of one of the cool-season beds with gobo and Shanghai pac choi to the left of the bird bath and mustard greens and cilantro on the right. A cut-and-come-again bed of stir-fry greens (below) is almost ready for harvesting.

The rest of the beds gave us more than enough vegetables for both families to have a stir-fry or two every week for about three months—great meals of carrot and snap pea stir-fries, chicken with broccoli, tatsoi with ginger, mixed greens with mushrooms and garlic, and oh so many more. Since that stir-fry garden, I have grown many smaller versions and still find them among the most satisfying cool-season gardens.

My stir-fry garden produced far more produce than my husband and I could ever use. My friend Henry Tran (above) comes by to cut some greens for stir-frying. Helen Chang (below) harvests cilantro from the stir-fry garden. A harvest from the Creasy stir-fry garden is shown on the opposite page.

The Creasy Summer Asian Garden

March was still colder than usual, but time yields to no one and it soon became the moment to start the summer vegetables, like peppers and eggplants, and the basils, and to order some of the Southeast Asian herbs. The seeds were planted in flats and kept on a warming mat a few inches from fluorescent lights. Germination was good and the plants were moved up to four-inch plastic pots in mid-April, but because it was so cold, they were kept under lights for a few weeks more. Finally they were so big they needed to be moved into larger containers and outside into my cold frame. Even April was very cold, so the plants were not put out until mid-May, when nighttime temperatures were finally above 55°F.

The weather remained colder than usual and July was the coolest on record—mostly overcast days in the high 60s. Some of the vegetables did splendidly in spite of the coolness including the squashes and cucumbers, the soybeans, leek flower, and onions. The eggplants and peppers did better in August as the weather improved—many days in the low 80s. However, my eggplants started to show signs of fusarium wilt (leaves randomly turning brown and the stems showing brown rings inside when cut.) They were in full production and it was painful but one by one we needed to pull them out. The yard-long beans, malabar spinach, and bitter melons, which all need hot weather, were still only three feet tall and never did produce. But all was not lost, by September the baby corn was ready—delicious—the hot peppers were in full production—spicy—and the cucumbers—over productive—and we were giving them away to all the neighbors. The ‘Siam Queen’ basil, bunching onions, amaranth, and the shisho all did well. And the winter squash ‘Autumn Cup’ was extremely productive and ran all over the garden. The squash themselves were rich and sweet.

All in all, the garden was a success but more stressful than most with all the cold weather. When I plant these hot-weather-loving vegetables again, I will start them under plastic hoops so they get more heat and I’ll plant my eggplants in containers. As always, the gardening adventure continues.

In my back garden (opposite) I designed a small herb garden that included the Asian herbs; mioga ginger, Oriental chives, lemon grass, and even a small container of experimental wasabe. (It is real tricky to grow and after a few months is up and has died.) Also in the beds were bush basil and winter savory. Last year’s summer Asian garden (above) had many successes: the bunching onions, lots of Japanese cucumbers and squashes, Thai and lemon basils, hot peppers, eggplants, and leek flowers. It was not hot enough for my malabar spinach, bitter melons, and yard-long beans to grow large enough to produce much.

Plants in the Warm-Season Creasy Asian Garden

Amaranth: ‘Green Leaf,’ ‘Red Leaf

Basil: Holy, ‘Thai’

Bunching onions: ‘Deep Purple’

Corn: ‘Baby Asian’

Cucumber: ‘Kidma,’ ‘Orient Express,’ ‘Suhyo’

Eggplant: ‘Millionaire,’ ‘Ping Tong’

Green onions: ‘Ishikura’

Luffa: Ridged

Peppers: ‘Cayenne,’ ‘Hot Asian,’ ‘Santaka’

Shisho: Green leaf

Shisho: Red leaf

Soybeans: ‘Maple Leaf

Yard-long beans: ‘Red Seeded,’ ‘White Seeded’

Winter squash: ‘Autumn Cup’

the Cunningham garden

David Cunningham lives in Vermont on a beautiful farm that sits on a knoll with a breathtaking view of the countryside.

David grew up there, and I couldn’t help thinking that he was clearly destined to go into horticulture. We sat down to plan the Asian garden together as soon as I arrived. Though I didn’t pay much attention to the information at the time, David mentioned that his mother was a wolf preservationist—and that the garden was encircled by a wolf yard, then surrounded by a field of sheep.

I returned in midsummer to see the garden, and at that time the wolves were much more in evidence. In fact, to visit the garden we had to exchange places with them; the two wolves went into the house while we went to the garden. Though the idea of being in close proximity to them unnerved me a bit, the wolves were actually quite lovable and shy.

In the garden, which is protected by an electric fence to keep out the wolves, David’s horticultural skills were abundantly manifest. The soil was beautiful—crumbly and dark—and obviously well cared for, and row upon row of healthy Asian vegetables attested to its quality. David told me that long ago the soil had been clay based but that in the early 1950s it started receiving care as a vegetable garden. In winter, the area is planted with winter rye, which in spring is grazed by sheep, and over the years the soil has been amended with mulches and compost. A few years earlier, David had incorporated twenty-five bales of peat moss into the plot. Always careful about keeping the soil healthy, the Cunninghams have kept planks on the paths to avoid packing down the soil because they plan to use it for beds in the future.

The overall vegetable garden is about thirty by forty feet in size, and David had planted a little less than half with Asian vegetables. We started reviewing the garden at the north end, which was planted with three varieties of edible-podded peas: ‘Dwarf Gray Sugar,’ ‘Mammoth Melting,’ and ‘Oregon Sugar Pod.’ “If I had to pick a favorite,’’ David told me, “I think it would be ‘Dwarf Gray Sugar,’ because it’s such a vigorous grower. It has reddish-purple flowers and the pods are very tasty. At one point, I thought I was going to lose all the peas, because we had a week of temperatures topping 90. All the varieties looked pretty sad for a while, but they perked right up again after it cooled down.”

David went on to describe the six varieties of cabbage-type greens he had planted in the next few rows. ‘Pac Choy’ has white stems, an open form, and doesn’t make heads. ‘Tyfon,’ a cross between Chinese cabbage and turnips, has a mild mustardlike flavor that, according to David, is good in salads. ‘Spring A-1’ is a cabbage with a medium-tight head and ‘WR 90’ an upright cabbage with a very tight head. ‘Winter Queen’ is a cabbage good for fall harvest, and ‘Tat Tsai’ is a dark green nonheading plant with spoon-shaped leaves growing out of its base.

In the next rows, David had planted the Japanese herb mitsuba, an aromatic parsleylike herb, and ‘Green Lance,’ a Chinese type of broccoli that David likes using in stir-fries. The head of this broccoli is open and the plant’s stem is mainly what is eaten. He had also planted two types of mustard: ‘Red Giant,’ a striking, somewhat spicy vegetable, and ‘Savanna’ mustard spinach, a mild-flavored green. The variety of daikon in the garden was ‘April Cross.’ David described it as very tender and uniform with no pith, woodiness, or hollowness. “When you start eating it,” he said, “it doesn’t seem hot, but it builds up. We eat it in stir-fries, but we’ve had it raw in salads to and are really happy with it.”

David Cunningham harvests cabbage from his Asian garden.

David was about to start his fall garden during my visit and was so pleased with the summer’s experiment that he wanted to try more varieties of the cabbages. This time he was planning to plant ‘Green Rocket,’ ‘Tsoi Sim,’ and ‘Taisai’ plus shungiku greens and a mustard spinach called ‘Osome.’

I asked David about pest problems, and he told me he had had flea beetles on some of the daikon plants and greens and an occasional problem with moles. He remarked that at one time the family had had problems with occasional rabbits, deer, and woodchucks and a serious struggle with raccoons whenever corn was growing. “But,” he added, in what I considered a masterful understatement, “since the wolves have been here, things have settled down a bit.’’

I left this Vermont pastoral scene with my concern about the adaptability of at least some Asian plants put to rest. Many of these wonderful vegetables could be well adapted to a non-Asian kitchen, and David was obviously enjoying both growing and cooking with them. In fact, as far as I was concerned, a fair number of these vegetables had passed the true cooking gardener’s test, as David was interested enough to try even more varieties the next season.