Читать книгу Inside the Dancer’s Art - Rose Eichenbaum - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

The legendary choreographer Martha Graham described those who possess an irrepressible inner force to move, stretch, run, and jump as being “doomed to dance.” I have met many dancers who fit that description.

After a thirty-year performance career, Nancy Colahan told me, “I am, and always will be a dancer. Every cell in my body is primed to be so.” Michele Simmons, an Alvin Ailey dancer who was later sidelined by multiple sclerosis and confined to a wheelchair, insisted to the end of her life, “My identity as a dancer will never, ever, ever, ever be taken from me. It’s who I am.”

In the words of Desmond Richardson, one of the greatest dancers of his generation, “I define dance as life—using your life experience to express yourself through your art.” Top-rated national competitive break-dancer, Trinity (Nicole Whitaker) put it simply, “Dance means everything. I’d die without it.”

Performance is how these individuals express who they are at the core. Tap dancer Jason Samuels Smith told me, “I am my most honest when I’m dancing. No one can own my thoughts, or my actions, or tell me how to feel.”

Spanish dancer Carmela Greco, daughter of the late flamenco star, José Greco, described dance as therapeutic: “Before every performance I feel a huge emotional weight—the weight of my life. But once I begin to move, the weight lightens and lifts away.”

The dancer’s art requires dedication, discipline, and sacrifice. Russian-trained ballerina Natalia Makarova explained how she had to tame her body in her quest to reach the top. “One must work the body like a racehorse. Rein her in and bring her under control. When she rebels, you must conquer her, become her master to bring body and mind into harmony.”

I asked former Broadway dancer and ballet choreographer Eliot Feld, “What is the payoff for all the sacrifices you’ve made for your art?” He replied, “I’ve learned that it’s unreasonable to expect rewards simply because you have given everything to make your dances. It’s a one-way street. The dances that you make owe you nothing. You owe them everything!”

Film star Shirley MacLaine, who performed on Broadway in Bob Fosse’s The Pajama Game, described dancers as “artistic soldiers” who “will do anything they’re asked.” The dancer’s job is to entertain, engage, and uplift an audience—and with that comes the responsibility to deliver one’s best performance.

Carmen de Lavallade, who for decades has mesmerized audiences with her beauty and talent, confessed, “You spend your entire life trying to elevate an audience to another level. You also spend your entire life afraid you might not.” As Tony Award winner Chita Rivera put it, “All I’ve ever wanted was to touch that one person out there in the dark.”

And yet, for all the training, long hours and, in most cases, low pay, dancers rarely know how much their performances truly affect an audience. Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater star Matthew Rushing explained, “Even though you receive applause, you usually don’t know how your dancing affects people. But when someone comes up to you after a performance with tears in their eyes and says, ‘You touched my spirit, you touched my soul,’ that’s when you know you’ve made a difference.”

New York City Ballet’s principal dancer Tiler Peck pondered, “What do I look like when I’m dancing? I really don’t know. I know what I feel like when my arms are doing this or when I’m in the air. But if I were someone sitting in the audience looking at me—what would they be seeing? Would they be able to read my thoughts and feel my emotions?”

Yuriko, the legendary Martha Graham dancer, asserted that the dancer’s art should be used as a tool for political awareness and as a force for social good. “Look at what’s happening in our world, in our century. Use your imagination and the human body to demonstrate life and the human condition.” Tap dancer Mark Mendonca agreed: “Dance is how I connect with the power we all have to change the world.”

Dance also operates on a spiritual realm, connecting us to a higher power. Choreographer Cleo Parker Robinson described dance as “a spiritual language we can use to feed our souls, communicate with each other, and show respect for all peoples.” For choreographer Judith Jamison, “The dancer is someone who makes you feel part of the universe.” Former Bella Lewitzky dancer, John Pennington, views dance as a way for artists to express what they know about their own spirituality.

As personally fulfilling as dancers’ lives can be, the duration of their stage careers are relatively short when compared to those of artists in other fields. Choreographer David Parsons spoke from personal experience when he lamented, “There comes a time when the body betrays you.”

So what does the dancer do when her body betrays her? Retired ballerina Martine van Hamel responded. “She must simply learn to live with her own demise. I don’t feel anymore like I’m a dancer, and yet, I’m nothing but.” When I asked the same question of veteran Martha Graham dancer Mary Hinkson, she said, “If you can’t do it, don’t do it. Why get on the stage and just hobble around?”

Many told me about the challenges of finding a balance between their personal and professional lives. They shared deeply personal stories and, in some cases, their darkest and most frightening moments. They recalled with pride their signature roles, reminisced about the invaluable relationships they had developed with other dancers and choreographers. They spoke eloquently and lovingly of their appreciation for the dance—how it had given their lives meaning and enriched it beyond their wildest expectations. Others confessed hurt and betrayal by an art form that can be fiercely unforgiving.

Whether starting out, at the height of their career, or looking back, dancers know that they have the ability to inspire, stimulate the imagination, communicate ideas and emotions, and offer commentary about ourselves and our world. Many feel compelled not only to uplift audiences, but humanity as a whole.

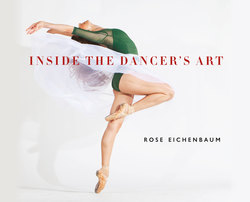

I know all this because long before I picked up a camera and tape recorder, I was a dancer. I too had dreamed of a career on the stage, but ultimately found my true calling as a dance photographer, author, and teacher.

My earliest influence as a photographer was Barbara Morgan, whose extraordinary skill at capturing moving bodies in time and space, artfully lit and composed, had a profound effect on my visual aesthetic. She practiced “previsioning,” an intuitive approach that prepared her to establish an empathetic relationship with her subjects as she searched for “meaning within form.”

It is through this method that Morgan captured so poignantly the personas and artistic expressions of Martha Graham, Erick Hawkins, José Limón, Anna Sokolow, Merce Cunningham, Doris Humphrey, and others. Her desire to take pictures that contained “the essential emotion of the dance and arrest time to capture the dance at its visual peak” made her images of the late 1930s and 1940s among the first to reveal the dancer’s spirit and artistry. When I studied her photos, I saw intimate portraits that conveyed what lies beneath technique, costumes, and character. She captured the dancers’ relationship to their art and of the art itself. Could I do the same? I vowed to try. The year was 1985.

For more than three decades, I’ve photographed hundreds of dancers of every style—from ballet, tap, jazz, and break-dancing to ballroom, postmodern, world dance, butoh, and the avant-garde—in dance studios, photo rental houses, and site-specific locations, in rehearsals and in performances. Regardless of the assignment, whether marketing a dance company or performance, shooting a magazine cover, publishing a book, or pursuing a personal project, it’s always been my intention, in the spirit of Barbara Morgan, to search for meaning within the form.

My thirty years as a photographer and chronicler of dance brought me in close contact with some of the most celebrated names in dance, as well as many talented emerging artists. Every such encounter contributed in some way to my understanding of the dancer’s life and art. This work is a record of my journey into the world of dance, and is dedicated to the dancers who I have had the honor to photograph and interview during the course of my exploration of one of humanity’s oldest and most impassioned forms of artistic expression.

Rose Eichenbaum