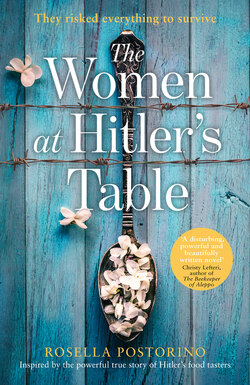

Читать книгу The Women at Hitler’s Table - Rosella Postorino - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4

ОглавлениеI was born on December 27, 1917, eleven months before the Great War ended, a Christmas gift to wrap up the holiday celebrations. My mother said Santa Claus had heard me wailing, bundled up beneath so many blankets in the back of his sleigh that he’d completely overlooked me. And so he flew back to Berlin, unwillingly though, because his vacation had just begun and the unscheduled delivery was an inconvenience. It’s a good thing he noticed you, Father used to say, because you were our only gift that year.

My father was a railroad worker, my mother a seamstress. Our living room floor was always covered with spools of thread and balls of yarn in all different colors. My mother would lick the end of a strand to thread the needle more easily, and I would mimic her. Once, without letting her see, I sucked a strand of thread and played with it on my tongue. When it had been reduced to a soggy clump, I couldn’t resist the urge to swallow it and discover whether, once inside me, it would kill me. I spent the following minutes wondering what the signs of my imminent death would be, but, given that I didn’t die, I soon forgot about it. Then at night I remembered it, certain my time had come. The game of death began at a very early age. I never spoke a word of it to anyone.

At night my father would listen to the radio while my mother would sweep up the threads strewn on the floor and climb into bed to open a copy of Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, eager to read the latest episode of her favorite serial novel. That was my childhood, the steamed-up windows looking out onto Budengasse, multiplication tables memorized well in advance, the walk to school wearing shoes that were first too big and then too tight, ants decapitated with fingernails, Sundays on which Mother and Father would read from the pulpit—she the psalms, he the Epistles to the Corinthians—and I would listen to them from the pew, either proud or bored, a pfennig coin tucked in my mouth. The metal was salty, it tingled. I would close my eyes in delight, my tongue pushing it to the edge of my throat until it teetered there, ready to slide down, then all at once I would spit it out. My childhood was books beneath my pillow, nursery rhymes sung with my father, blind man’s bluff in the square, stollen at Christmas, trips to the Tiergarten, the day I went to Franz’s crib, stuck his tiny hand between my teeth, and bit down hard. My brother howled like all newborns howl when they wake up, and no one found out what I had done.

It was a childhood full of sins and secrets, and I was too focused on their safekeeping to notice anyone else. I never wondered where my parents found the milk, which cost hundreds and later thousands of marks, if they held up a grocery store and eluded the police. Not even years later did I wonder if they felt humiliated by the Treaty of Versailles like everyone else, if they too hated the United States, if they felt unjustly treated for being held responsible for a war in which my father had fought. He had spent an entire night in a foxhole with a dead Frenchman and had eventually dozed off beside the corpse.

During that time, when Germany was a gridlock of wounds, my mother would pull back her lips as she slicked down the end of the thread, on her face a turtle expression that made me laugh, my father listening to the radio after work, smoking Juno cigarettes, and Franz napping in his crib, his arm bent and his hand by his ear, his tiny fingers curled over his palm of tender flesh.

In my room I would do an inventory of my sins and my secrets, and would feel no remorse.