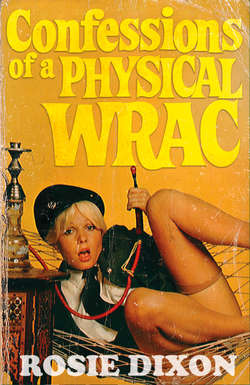

Читать книгу Confessions of a Physical Wrac - Rosie Dixon - Страница 6

CHAPTER THREE

ОглавлениеThe next morning, I am standing on the steps of the Army Recruiting Office, waiting for it to open. It is not a decision I have come to overnight and the awful misunderstanding of the previous evening is only partly responsible for it. When I find that Penny was merely applying a sticking plaster to Geoffrey’s injured nose and – and not doing what I thought she was doing, then I feel like killing myself. My whole future blighted by sheer bad luck. The cup of romance dashed from my lips. It is all so unfair.

I try to explain things to Geoffrey but he is very unsympathetic. ‘I could understand it if it was anyone else than Derek Tharge,’ he keeps saying. ‘He’s the kind of chap who pees in the shower. He’s always moving his name up the ladder when he thinks no one’s watching and I’m positive he pinched one of my balls. I wouldn’t be surprised if he was the chap who left the net up all night on number three court and pulled the uprights out of the ground.’

‘Forget Large – I mean Tharge!’ I implore him. ‘He means nothing to me. He was just an instrument. I was distraught, Geoffrey. I didn’t know which way to turn.’

‘You seemed to be turning in a lot of directions when I found you,’ says Geoffrey unkindly. ‘I was coming to ask you if you wanted a hot pasty, too.’

‘That was very sweet of you,’ I say. ‘Oh Geoffrey. Can’t we pick it up from there? Can’t we take it from the hot pasty and forget that this unfortunate incident ever took place?’

But Geoffrey is not to be placated and we part with him muttering about how I am always blowing hot and cold and he does not know where he is with me. The last I see of Derek Tharge he is inserting some kind of inhalant up his over-large nostrils and enquiring if anyone has any glucose tablets.

I can’t bring myself to reveal to Penny what I thought might be taking place in the tea-room and so I have to brave her fairly foreseeable comments on my actions.

‘I have to hand it to you,’ she says. ‘You don’t let the grass grow under your feet, do you? In fact the grass has a bit of a job growing anywhere within twenty yards when you swing into action. How did this entrant measure up?’

I avoid answering that question and spend a sleepless night wondering what to do for the best. As I said right at the beginning, Reggy’s arrest does mean that I will have to look for another job – this time, preferably, one that pays a salary. I can’t go on living on promises. That, of course, is something that can be said for accepting a job with a government organisation. The money isn’t always good but you do know that you are going to get paid every week.

I don’t want to live at home because, as much as I love Mum and Dad, we do get on each others’ nerves after a while and the same can be said of Natalie, only more so. What I do want is to find some career that offers me protection from men. Now that true marital happiness seems to have been snatched from my grasp by cruel fate, I do not want to find myself drifting back into those kinds of situations which have led to so much unpleasantness in the past. I want to turn my back on men for a bit. A nice, quiet monastic life is what I need. In fact, I have thought about becoming a nun but I don’t think it is quite me. To be brutally honest, I have never really fancied the uniform and I don’t think I possess sufficient religious conviction to stand all the kneeling. The Women’s Royal Army Corps could be just what I am looking for. Regular pay and meals and the companionship of lots of girls of my own sex. Living with them and concentrating on making a go of my new career will protect me from those unsought involvements which have been so damaging in the past.

‘Hello, darling. Hope you haven’t been here long? Hang on to these a minute while I find the blooming key.’ The man with the shoulder-length hair sprouting from his peak cap thrusts a bundle of doormats into my hand and fumbles in the pocket of his khaki uniform with the Sergeant’s stripes on the shoulder. ‘Lovely article they are. Empire made, every one of them. I was lucky to get ’em. There’s a big run on them at the moment. Come about the typing job, have you?’

I step back and take another look at the sign above the window showing the cut-out figures of five laughing soldiers sticking bayonets into a scarecrow. No, I have not made a mistake. The sign says it quite clearly: ‘Army Recruitment Centre.’

‘I wanted to find out about becoming a WRAC,’ I say.

‘Blimey!’ says the man. ‘Well, you came to the right place, didn’t you? Step inside and we’ll see what we can do. All right for pan scourers, are you?’

I am not a little surprised to find that the interior of the room we go into has more in common with the hardware counter of Woolworths than Her Majesty’s Armed Forces. There are piles of dusters, plastic bowls and buckets, nutmeg graters, tea strainers, cheese graters, assorted cutlery and plates.

‘Are you sure I’ve come to the right place?’ I say. ‘This is a recruitment centre?’

‘Latest model Mark I,’ says the Sergeant, brushing his hair behind his shoulders as he opens a cupboard and a pile of pamphlets fall on the floor. ‘You can see why I need an assistant, can’t you? You wouldn’t fancy the job rather than joining up? The money’s better.’

‘Look,’ I say. ‘I don’t understand. All those dusters and things. What have they got to do with the Army?’

‘They keep down the overheads, don’t they?’ says the Sergeant. ‘That’s important these days. It costs a few bob to keep one of these places open, I don’t mind telling you. The government’s very worried about it – especially this lot. Between you and me, they’d close the Armed Forces down tomorrow if there was any work for the poor bleeders to do when they were demobbed. Them and all the blokes who make the bullets and the bromide tablets.’

‘I still don’t quite understand what that’s got to do with the doormats,’ I say.

‘They are nice, aren’t they?’ says the Sergeant. ‘Shall I wrap a couple up for you? They make wonderful gifts.’

‘It seems to me you’re more interested in selling things than recruiting people.’

‘You don’t miss much, do you?’ says the Sergeant. ‘Tell you what I’ll do. You buy three mats and I’ll have “welcome” stencilled on them for nothing. I can’t say fairer than that, can I?’

‘Are you really a Sergeant?’ I say.

‘Course I am! On a part-time basis. I’ve taken on the recruitment as well as all the other stuff I handle. That’s how the government’s cutting down on its defence budget. It makes sense when you think about it. I mean, keeping this office open just so a couple of geezers could wander in because it was raining, would be blooming stupid. The country can’t afford the manpower either. There’s so few people coming forward that all the able-bodied men – and women – are needed up the sharp end. Now, what about those mats? Supposing I threw in a free bottle of carpet shampoo?’

‘No thank you,’ I say. ‘I’d like some details of –’

‘And a sponge. I don’t mind throwing in the sponge. That’s the secret of my success. I’m not proud. When things start going against me I throw in the sponge and do something else.’

‘Please!’ I say. ‘What do I have to do to make you understand that I don’t want to buy any mats. I want to join the WRACs!’

‘All right. All right! You don’t have to shout. You can’t blame a man for trying to make a living.’ The Sergeant tips his hat on to the back of his head and pulls open a drawer. A pair of silk bloomers are revealed which he throws on to the desk. ‘That was a lovely line. I’ve got two pairs left. You wouldn’t be –’

‘No!’ I say.

‘Not even if I – no! Right let’s get down to business. I know the papers are in here somewhere. You can write your own name, can’t you?’

‘Of course I can.’

The Sergeant nods and spreads a piece of paper across the desk. ‘Good. Because that is important. An ability to sign a piece of paper with an accurate representation of your own name can take you a long way in any branch of the forces. Now, I’ve got to ask you a few questions. Have you ever had any anti-social diseases? By that, of course, I mean diseases that you get from being over-social.’

‘I don’t know what you mean,’ I say.

‘That must count as a “no”,’ says the Sergeant. ‘Now, are you married, divorced, a lesbian, or any combination of the three?’

‘I’m none of those things,’ I say.

The Sergeant nods approvingly, writes something on his piece of paper and turns it round so that it is facing me.

‘That’s the clincher,’ he says. ‘You’re the perfect recruit – in fact you’re almost too good to be true. Sign where I’ve put the plus sign. I used to put a cross but it confused the people at records. When recruits signed with a cross they used to think it was a double-barrelled name.’

‘Is this all I have to do?’ I ask.

‘Just about,’ says the Sergeant. ‘There’s the medical but you’ll waltz through that if you’re sufficiently co-ordinated to sign your name.’

‘Hold on a minute,’ I say. ‘You don’t give me the medical, do you?’

‘Good heavens, no,’ says the Sergeant. ‘You have a proper doctor for that. You didn’t think I was going to examine you, did you. Goodness gracious, how very unethical. No, I just measure you for your uniform. Take your dress off, please.’

My sigh of relief expires abruptly. ‘I can’t believe that you’re responsible for fitting out recruits,’ I say.

The Sergeant clicks his tongue in irritation and throws back a curtain. Revealed to my startled eyes are rows of battle dress uniforms, greatcoats, khaki skirts and even festoons of hand grenades, rifles and machine guns. ‘Do you believe me now?’ he says. ‘It’s another brilliant idea from the Ministry of Defence: Army Surplus with a difference.’

‘What’s the difference?’ I say.