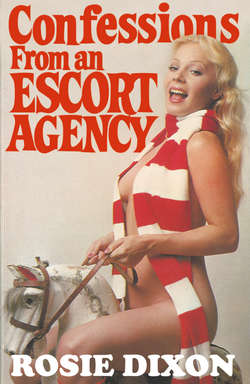

Читать книгу Confessions from an Escort Agency - Rosie Dixon - Страница 6

CHAPTER 1

ОглавлениеWhen I get back from St Rodence I am thrilled because Penny has asked me down to stay at her country seat – or rather, her father’s country seat. It is just what I need to buck me up because I am very upset about the school closing down – especially with all the related unpleasantness. (For unspeakable details read Confessions of a Gym Mistress, published by Futura.) Chedworth Place sounds awfully grand and I know that the Cotswolds are very sought after. Mum and Dad went on a coach trip to a place called Bourton-on-the-Water and said that it was very nice except for the coaches parked everywhere.

Where we live in Chingford – or West Woodford as Mum calls it because it sounds posher – is not very grand. Still, it is home and I am glad to be back there, even if it is my younger sister Natalie who answers the door. One has to excuse Natalie her flighty ways because she is going through an awkward age but I do feel that Mum and Dad should take a stronger line with her. This feeling is soon reinforced.

‘Oh,’ she says. ‘It’s you.’

‘Who were you expecting?’ I say.

‘Nobody.’

I notice that two of her blouse buttons are undone and that there is a red patch on the side of her neck. I may be wrong but those look like tooth marks in the middle of it.

‘Why aren’t you at school?’ I ask.

‘We were going to have games but the pitch was too muddy.’ She looks over her shoulder nervously.

It has not rained for three weeks but I make no comment on the fact.

‘Do you mind if I come in?’ I say, allowing a trace of sarcasm to creep into my voice. ‘After all, I do live here.’

Natalie shoots another nervous glance over her shoulder. ‘Oh yes. Of course.’

This is so unlike the normal Natalie. She has not said anything rude yet.

‘You’ve got somebody in there, haven’t you?’ I say, nodding towards the front room.

‘A friend,’ says Natalie uncomfortably. She plants herself in front of the front room door but I put down my suitcase and step past her. A boy of about sixteen is sitting on the edge of the settee and staring intently at the telly. I notice that his hair is ruffled and his shirt hanging out at the back. Ten seconds after I have opened the door a picture appears on the screen. ‘He came to watch the television,’ says Natalie.

The boy turns his head for an instant and gives what might either be a nod or a nervous twitch.

‘Do you usually watch ‘Play School’ together?’ I ask. ‘And why only one shoe? Is it so that you don’t damage the carpet when you hop around to Mrs Cluckabiddy’s song?’

‘I had a stone in my shoe,’ says the boy. ‘You trying to be sarky?’

‘She never stops,’ says Natalie turning to me. ‘Do you want a hand to carry your suitcase upstairs? I’m certain you’d like to go and unpack.’ That is more like the old Natalie.

‘Where’s Mum?’ I say, ignoring the hint.

‘She’s gone down the Parkwood Hill Ladies Social Club.’

‘Oh, playing bingo?’ I say.

Natalie shrugs her shoulders. ‘’Spect so.’ She is making faces at her boyfriend and I notice that his shirt is hanging out of his fly. I get a nasty shock for a moment. I am about to go out when there is an enormous bump on the ceiling above our heads. My bedroom.

‘Who else is here?’ I say. ‘What’s going on, Natalie? Does Mum know about this?’

Natalie does not answer but goes to the door and shouts upstairs, ‘My sister is home, ’reen. You coming down?’

‘It’s either her or the ceiling,’ I say. ‘How often do you throw the place open, Natalie?’ Just at that moment there is a ring on the front door bell.

‘That must be Tiger,’ says Natalie.

‘He said he was coming on his bike,’ says the boy, producing a comb from his pocket and running it through his hair. He looks up at me and wrinkles his nose. ‘You don’t fancy going to the pictures, do you?’

‘You going to give me 40p, are you?’ I ask, sarcastically.

‘You want an ice cream as well, do you?’ he says.

‘It’s Sonia,’ says Natalie turning away from the lace curtain. ‘She’s brought some records.’

‘This is ridiculous,’ I say. ‘Does this go on every time you don’t play games?’

‘We help each other with our homework,’ says Natalie’s friend putting away his comb and stretching.

‘What homework?’ I ask.

‘We didn’t have any today.’

‘Natalie—’ I begin. But she has gone to open the front door.

In the end I have to stay with them the whole afternoon. It is probably just as well that I do because goodness knows what they would get up to by themselves. My bedroom is unbelievable: bedclothes everywhere and some hideously spotty youth prancing about in his underpants. The whole thing reminds me of that terrible time when I was attacked by the three greasers (Confessions of a Night Nurse). Fortunately, this lot are easier to control although I do get fed up with being called ‘grandma’. After all, I am still several months short of my twentieth birthday. About five o’clock they disappear as if by magic, and five minutes later Mum comes home. Natalie and I are doing the washing up.

‘Rose, dear! What a lovely surprise. We weren’t expecting you back till next week.’

I give Mum a censored version of the events of the last few days and she shakes her head in sympathy. ‘It’s terrible what they’re doing to the countryside, these days. There’s too many cars as it is. All these roads just encourage them. Fancy your nice school having to go. I think we read something about it in the paper.’

I do remember reading a headline saying ‘School boy gang-raped’ but fortunately this is not the one Mum saw. It was terribly exaggerated anyway and the boy told the doctor that he quite enjoyed it – till he lost count and consciousness. The Lower Fourth always were terribly high spirited.

‘Have you thought about what you’re going to do now?’ asks Mum.

‘She’s going to be a hostess,’ says Natalie before I can clap a hand over her mouth. I might have known that it was an act of insanity to tell Natalie anything in confidence.

‘Not an air hostess?’ says Mum looking worried. ‘I’ve just been reading this book called The Jumbo Jet Girls and I wouldn’t like to think—’

‘Oh no, Mum,’ I say. ‘Nothing like that. Did you—’

‘Going out with strange men,’ says Natalie. I wonder how long you get for killing your sister, these days?

‘Oh no,’ says Mum. ‘You’re not going to sit in some club, are you? The whole thing was exposed recently. I don’t want you drinking all that coloured water. You never know what’s in it.’

‘Natalie’s got it wrong,’ I say. ‘I’m going to be an escort not a hostess. There’s a world of difference. There’s nothing sleazy or unpleasant about what I’m going to do.’

‘What are you going to do?’ says Mum.

‘I don’t know all the details yet,’ I say. ‘Basically, the job consists of providing female companionship for businessmen or tourists who find themselves in London without a wife or loved one.’

‘“Loved one”?’ queries Mum.

‘I meant “loved one” in the loosest sense,’ I say.

Mum’s eyebrows shoot upwards again. ‘I don’t mean “loose” like that!’ I yelp.

Honestly! It is so difficult to explain, isn’t it? I could slap Natalie’s wrist for putting me in this spot – in fact I think I will when I get her alone upstairs.

Why Mum should be so worried I cannot understand. I have never made any secret of my moral standpoint, which is remarkably severe for these lax times we live in. Not for me the casual ‘easy come, easy go’ attitude which characterises Natalie’s approach to relationships. Every time I embark upon any form of contact with a member of the opposite sex I carry with me the realisation that I need to preserve the precious dowry of my virginity for my eventual ‘Mr Right’. How can any girl expect to be respected if she does less? – even more important, how can she respect herself?

But these are difficult times and it behoves one to develop a philosophy which, to those without a keen sense of moral values, might smack of compromise. It has always been my conviction that virginity is a state of mind, and this belief has carried me through many situations which might have placed an unbearable strain on those who had not selected their colours and pinned them to the masthead.

I can think of occasions on which I have lain powerless before the onslaught of some gigantic pussy pummeller and yet been able to endure the situation – nay, even draw some strange satisfaction from it – because my mind was pure from taint. I was able to perceive that I was in a situation not of my own making, or, alternatively, one that I had entered into for reasons other than those of personal gratification. In such circumstances, how could it be said that my virginity – my mental virginity – was affected? When the base Geoffrey plied me with drink, or I intervened between my sister and the greasers, my principle was never compromised. I was an agent of circumstance.

I am sorry to digress in this way but I think it important to get what you feel straight. I am certain that many girls would get much more out of life if they assessed their position and took a firm stand.

‘I don’t like the sound of it at all,’ says Mum.

‘Make up your mind when I get back from Chedworth Place,’ I say. I had expected the mention of such a posh spot to be received with a mild attack of drooling but Mum looks even more worried.

‘Where’s that?’ she says.

‘It’s in the Cotswolds,’ I say. ‘I’ve been invited to stay by my friend.’

Mum follows the trail ruthlessly. ‘Is she something to do with this escort business?’

‘Yes. She knows somebody who runs it.’

Mum wrings her hands. ‘Oh dear. I don’t like the sound of this at all. It’s difficult to know how to put it, but—’

‘White Slave Trade,’ interrupts Natalie, eagerly. ‘They’ll drug you and then you’ll wake up in a brothel in Port Said. Thousands of Arabs will be tasting the fruits of your body at knockdown prices.’

‘Natalie! That’s quite enough of that!’

‘It’s true, Mum. I read about it in the paper.’

‘Not in the Sunday Telegraph, you didn’t.’

‘You’re both jumping to conclusions,’ I say. ‘I’ve known Penny since we were nursing together. She’d never get involved in something like that.’

‘Well, let’s wait and see what your father says. I don’t think he’s going to like it.’ Natalie shakes her head in time with her mother and I could drag my nails down her cheek. The little baggage has always been the favourite, especially as far as Dad is concerned, and it is always me who gets the blame for everything. I waste no time in making my feelings clear and retire to my room in tears. Somebody has been using the perfume that Geoffrey gave me, which does not improve my mood.

Some of you may remember that Geoffrey Wilkes is my long-suffering boyfriend who has stuck with me through thin and thin. I know I treat him badly but he is so eager to please that he turns me right off. If you see a door mat it is difficult to avoid wiping your feet on it.

I don’t know whether it is telepathy or something like that but while I am lying on my bed, and thinking about Geoffrey’s funny little ways, and how sweet he is really, I hear the telephone ringing downstairs – it would be alarming if I heard it ringing anywhere else. Immediately, I have a strange feeling that it is Geoffrey. Amazing, isn’t it? It just goes to show that there are so many things in this life we can never understand. I wait with bated breath as I hear footsteps coming upstairs and prepare myself for the inevitable.

‘It’s your friend,’ says Natalie’s sulky voice from outside the door. Just as I thought! A new eagerness pushes my body from the bed and I trip downstairs rehearsing my greeting. The telephone is lying on the hall table and I pick it up and place it to my lips.

‘Hello! Rose here!’ I trill.

‘Hello. Did you get home without being raped?’

‘Yes,’ I say, bitterly.

‘You don’t sound very happy about it.’

‘It’s not that,’ I say. ‘I thought you were someone else.’ Of course, it is Penny, not Geoffrey. How typical of her.

‘If you’re expecting a call, I’ll get off the line.’

‘There’s no need. I just had a feeling, that’s all.’

‘Lucky you, old girl.’ Penny has a very crude streak which I try to ignore. ‘I was just ringing up to see if you’d like to come down this evening. There’s a train from Paddington at six. I could meet you at Oxford.’

I begin to cheer up. When Dad hears the news about my possible new job he will make Mum’s comments sound like hysterical enthusiasm. I don’t feel in the mood for a long inquest and a speedy departure to Chedworth Place will solve all my problems.

‘That’s very kind of you—’ I begin, trying to be polite.

‘Of course, if you’d rather spend a bit of time with your family, I’d quite understand. It’s just that I got invited to this party at St Peter’s Hall and I thought it might be fun if you came along. Shall I ring you in a few days and—’

‘I’d love to come,’ I say hurriedly. ‘Six o’clock, did you say? Right, I’ll be on it.’ It occurs to me that I am veering to the other extreme of enthusiasm but it doesn’t matter because Penny is already describing the delights that the evening has to offer.

‘… bumps supper, throwing up everywhere, some of the younger dons aren’t bad but they spend too much time postulating.’ I blush at the end of the telephone line. Penny is a great one for indulging in revealing detail. As far as I am concerned, what the younger dons do in the privacy of their rooms is their own business. We live in the twentieth century and provided that it does not hurt anyone else I think that people should be allowed to do what they like.

Despite the questionable behaviour of the junior dons the thought of visiting Oxford appeals to me tremendously. I have always dreamed of going to one of those big balls when everyone dances on the lawns and drinks champagne till the early hours of the morning before climbing into a punt and rowing down to Rochester for breakfast. I wonder if Penny’s party will be like that? Whatever happens, it will be marvellous to see the inside of an Oxford College. By the time I put the telephone down, I am really excited and I can hardly wait to see the expression on Natalie’s face when I tell her where I am going. She will be green with envy. I am on my way to spread the good news when the phone rings again. Curse the thing! I have not got a lot of time to waste if I am going to catch that train.

‘Hello,’ I say, slightly irritably.

‘Rosie? Is that you? It’s Geoffrey here. What a smashing surprise. I was ringing up to find out when you were coming home?’

‘In a few days,’ I say. I wish I could sound more welcoming but I am a bit annoyed at how Geoffrey let me down when he turned out to be Penny. It is a very shabby thing to interfere with someone’s telepathy.

‘But you are home,’ says Geoffrey sounding puzzled.

‘I’m going down – I mean, up to Oxford,’ I say, practising the delivery I will be using with Natalie. ‘I’m going to stay with some people in the country.’

‘Are you free this evening?’ says Geoffrey. ‘I thought we might go to the flicks. There’s a smashing movie called Confessions of a Window Cleaner. Very funny.’

‘Confessions of a Window Cleaner!?’ I say. ‘Do you really think I’d go and see something like that? I can just imagine what it’s like. Nudity and filth.’ How insensitive of Geoffrey to mention something like that when I have told him that I am going to Oxford. He exposes himself sometimes.

‘It was just a thought,’ he says. ‘We could always go and see “Thud”. It’s a fearless exposure of the man behind all the fearless exposures of police corruption and brutality.’

‘Thank you, Geoffrey,’ I say, politely. ‘But I’m afraid my train leaves at six. There won’t be time to go anywhere.’

‘Oh dear. What a shame. I was so excited when I heard your voice.’ My heart softens. He is not a bad old stick. ‘Do you think Natalie would like to see Confessions of a Window Cleaner?’

My heart hardens. Not only insensitive but tactless to boot.

‘Why don’t you ask her?’ I say icily. ‘She’s just popped out to buy a tin of Valderma. She’ll be back in a minute.’ Something about my tone must tell Geoffrey that he has caused offence.

‘Don’t get shirty, old girl,’ he pleads.

‘Don’t call me “old girl”!’ I rant. ‘It sets my teeth on edge.’

‘Sorry, old girl – I mean, look—’ There is a pause while Geoffrey splutters. ‘Tell you what. Why don’t I run you to the station? It’s not an easy journey and it will give us a chance to have a talk. Also,’ Geoffrey begins to sound pleased with himself, ‘you’ll be able to see my new motor.’

‘Not that Japanese thing?’ I say.

‘No, I got rid of that. It occurred to me that it was a bit unpatriotic to run a foreign car when our motor industry was struggling.’

‘What made you suddenly think of that?’

‘Some bloke kept chucking notes through the windows.’

‘I can’t see why that influenced you.’

‘They were wrapped round bricks.’

Poor Geoffrey! He does seem to attract trouble like a magnet. I should be warned really.

‘The doors were very difficult to open from the inside, weren’t they?’ I say.

‘No handles, you mean?’ says Geoffrey. ‘Yes, I think that had something to do with it being made by the people who turned out those Kami Kaze planes.’

‘Uum,’ I say. I am thinking about Geoffrey’s offer. It is a long way to Paddington and a lift would be a big help. ‘Do you think you could get round here in half an hour?’

When Geoffrey turns up it is in an old Daimler that looks like a hearse. I feel that I am going to be taken to Paddington cemetery rather than the station.

‘Plenty of room, eh?’ says Geoffrey proudly.

‘Have you got the other one in the back?’ I say. ‘It’s enormous.’

‘Guzzles petrol but it’s rather a splendid old bus,’ says Geoffrey. ‘Have you got your case?’

Mum pops out the minute that Geoffrey crosses the threshold, because she reckons that he is a wonderful catch for me. ‘Isn’t she a lucky girl?’ She trills. ‘Always gadding off somewhere. My, my. Isn’t that a beautiful old car. Is it yours, Geoffrey?’

‘Just about.’ Geoffrey shuffles from one foot to the other and makes funny faces as if he is trying to swallow something.

‘You are going to be in demand.’ Mum looks at me. ‘You’re lucky that Geoffrey has the time to spare to take you to the station.’

‘We’d better be going, I think,’ I say, before Mum can start calling the banns.

‘Yes.’ Geoffrey knocks the telephone off the table and dives down with Mum to pick it up. There is a painful crack of heads and I walk out and put my suitcase in the car. As I do so, Dad appears looking as if the cares of the world weigh heavily on his shoulders.

‘Are you coming or going?’ he says.

‘I’m going to stay in the country for a few days,’ I say.

‘Is it the holidays already?’ he says.

‘The school had to close down. It was all a bit of a—’

Dad holds up his hands. ‘Don’t tell me. I can imagine. You’re out of a job again, that’s what it boils down to, isn’t it?’

‘If you put it like that, yes,’ I say. Dad’s parents obviously never put him through charm school. He hasn’t even said ‘hello’ yet. ‘I’m going to discuss a new job with the people I’m staying with.’

Luckily, before I have to get involved in any embarrassing details, Geoffrey comes out of the house. ‘Evening Mr Dixon,’ he says, stepping into a flowerbed so that Dad can pass.

‘That’s one of my wallflowers you’ve got your foot on,’ says Dad.

‘Oh, I am sorry.’ Geoffrey takes another step backwards and sits down in the garden pool.

I close my eyes. This does not bode well for our trip to the station.

‘Don’t pull on that—’ Dad’s voice breaks off at the same moment as the head of the stone cherub that was standing beside the pool. Geoffrey tries to replace the head in a number of positions and then lays it on the bird bath the cherub is holding.

‘I’m awfully sorry,’ he says. ‘I’ll get you another one.’

I can see the whites of Dad’s knuckles as he clenches his fists. ‘Don’t leave the head lying there,’ he says. ‘It looks like John the Baptist saving Salome the trouble.’

‘Oh very good,’ says Geoffrey. ‘Did you hear that—?’ His voice trails away when he reads the expression on Dad’s face. ‘Sorry again, Mr Nix–Dixon. I’ll–er—’ Geoffrey trips over the brick edging to the garden path and throws his arms forward so that the cherub’s head describes a graceful semi-circle and shatters a cucumber frame.

‘Come on, Geoffrey. We must be going or we’ll miss the train,’ I say helpfully.

‘Get out!’ screams Dad. ‘Get out!!’

‘I’m sorry,’ says Geoffrey. ‘I’m terribly sorry.’ He tries to close the garden gate behind him and the catch snaps off.

‘Don’t touch anything!’ I beg him. ‘Whatever you do, don’t touch anything!’

Geoffrey is shaking when he gets in the car and he tries three keys before he finds the right one for the ignition.

‘She’s a bit stiff,’ he says. ‘I wish that damn fool hadn’t boxed us in behind.’

‘Careful,’ I say. ‘That’s—’ I am going to say ‘Dad’s car’ but after Geoffrey has backed into it there doesn’t seem much point. I don’t want to upset him unnecessarily.

‘Are we all right on that side?’ asks Geoffrey. I wrench my eyes away from the water seeping out of Dad’s radiator and shoot a quick glance at the car in front. Dad has heard the crash and is coming down the garden path – fast.

‘I think so,’ I say. As it turns out, I am wrong, but we only catch the car in front a glancing blow before pulling out into the middle of the road. ‘What’s the acceleration like?’ I ask. Fortunately, Geoffrey is able to show me, just as Dad lunges for the door handle.

‘Very good,’ I say.

Geoffrey glances in the rear view mirror. ‘Why’s that chap lying in the middle of the road, shaking his fist at us?’ he says.

‘I don’t know,’ I say. ‘Mind out, you’ll hit this milk float!’

‘Which milk float?’

‘The one you’ve just hit,’ I say, looking over my shoulder. Honestly, I have never left Chingford with a greater sense of relief. If we are going to have an accident I would much rather we had it somewhere other than on my own doorstep.

It soon becomes clear that Geoffrey is in a terrible state and not at all at ease at the wheel of the mighty Daimler. He is crawling along and at this rate it is obvious that we are going to miss the train. The rush hour traffic doesn’t help, either.

‘Don’t you know any short cuts?’ I say, beginning to get desperate. ‘You’ll find it easier in the side roads anyway.’

As it turns out, I am wrong. With cars parked all over the place it is very difficult to manoeuvre and we soon find ourselves going slower than ever. I am rather angry with Geoffrey for accepting my suggestion but I try and control myself.

‘We’ll have to get back on the main road,’ I say. ‘Pull out now! Come on!!’

‘But it’s a funeral,’ says Geoffrey.

‘It doesn’t matter,’ I say. ‘Come on, Geoffrey! We’ll be here for ever if you don’t get a move on.’ Still grumbling, he does as I tell him and we fall in behind the car which has the coffin in it.

‘Lovely flowers,’ I say. Geoffrey must be sulking because he does not say anything. Five minutes later, the hearse takes a sharp right turn and we carry on.

‘Try and make a bit of speed now,’ I say. ‘Surely you can overtake him.’

Geoffrey says something about back-seat drivers but he does as I say – Geoffrey always does as I say – and puts his foot down.

‘Well done,’ I say. ‘I think maybe, next time, you’d better do it on the outside.’

‘I thought he was going to turn right,’ says Geoffrey. ‘Ooops!’ We get past the fire engine all right and I look back to make sure that we have not given any of the men clinging to the side the brush off. I am most surprised when I see another Daimler clinging to our tracks – and another – and another!

‘Geoffrey!’ I say. ‘How awful. They’re following us.’

‘The police?’ Geoffrey stands on the brakes and I see the whites of the driver behind’s eyes as he tries to avoid going into the back of us.

‘No, the funeral party.’

Geoffrey looks over his shoulder and shares my view of the black hats, veils and sombre expressions.

‘Gosh! We’d better stop and tell them.’

‘There isn’t time,’ I squeak. ‘It’s touch and go as it is. Keep going and I’ll attract their attention.’

I should have said try and attract their attention. I have never met such a load of zombies. I wave my arms about and shake my head and point to the side streets and there is no reaction at all – apart from one woman who bursts into tears. The others just stare at me.

‘Here we are,’ sings out Geoffrey. ‘Damn! There’s a great queue of cars.’

‘Go up where it says “Taxis Only”,’ I say. ‘This is an emergency.’

Well, I must say. I am very disappointed in the attitude of the taxi drivers. I had always thought them such a bluff, cheerful lot, hadn’t you? The kind of people who would give you the shirt off their back in an emergency. The lot we bump into outside the station would not give you an old surgical support. I suppose it is unfortunate that five Daimlers follow us into the taxi rank but it is not our fault that people with suitcases start wrenching open the doors and climbing inside the minute they have stopped.

‘West London Air Terminal and step on it!’ I hear one of them shout.

‘’Ere! What do you think you’re doing!?’ says a large man with a red face and a luggage label fastened to his lapel. Before Geoffrey can open his mouth, the man starts dragging him out of the car and shouting ‘Bleeding minicab drivers!!’ Mini cab, I ask you! It’s ridiculous, isn’t it? The Daimler is built like a furniture van.

I am trying to say goodbye to Geoffrey when a very agitated woman dressed in black runs up to me and says, ‘Where’s my Dick?’

For a moment I don’t know what to say. I mean, I am a little overwrought and there are some very funny people about. Then it dawns on me. Dick must be the deceased.

‘I think he went up to High Holborn,’ I say. ‘You shouldn’t have followed us. We’re nothing to do with the funeral.’

For some reason the woman reacts very badly to this and tries to hit me with her umbrella. I know she is under strain but, really, it is a bit much with all the problems I have. Geoffrey is sinking to his knees under a rain of blows and all around me there are scuffles breaking out as the funeral party refuse to leave their cars, people try to scramble into them with suitcases, and cabbies assault the drivers. Sometimes I think that all this stuff about the British remaining cool in emergencies is blooming rubbish.