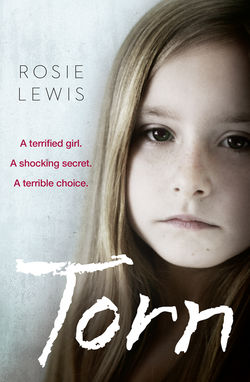

Читать книгу Torn: A terrified girl. A shocking secret. A terrible choice. - Rosie Lewis - Страница 7

Chapter One

ОглавлениеMaisie Stone eased the end of a biro between the wiry roots of her thick auburn dreadlocks, half-closing one eye as she twirled it around. Turning the radio on to mask our conversation, I reflected that the social worker wasn’t exactly what I’d envisaged when we’d spoken earlier that day, but then neither were the siblings waiting miserably upstairs in the spare room.

‘So, Rosie, this is kind of awkward,’ Maisie lisped, the words rolling over her silver-studded tongue so slowly that it was as if she needed winding up. Over the telephone she had spoken with such slow deliberateness that in my head she was nearing retirement. The woman sitting in front of me, with a thin leather bandana tied around her hair and taffeta skirt skimming her sandalled feet, had taken me completely by surprise. With her full lips and wide green eyes, there was an earthy appeal about Maisie, but the skin beneath her eyes was swollen and dotted with blemishes. By the way she was dressed I guessed she was in her early thirties at most, but somehow she seemed much older. Either that or she hadn’t slept in days. ‘When I picked them up I couldn’t believe there was one of each.’

‘You’d never met them before?’

Maisie’s beaded dreadlocks jingled as she shook her head. ‘No, their file landed on my desk at half past ten this morning. I only had time for, like, a quick flick through and when I saw Taylor described as a massive Chelsea fan I just assumed, what with her name and everything –’ her words trailed away and then she groaned, pulling her hands down her face. ‘Is there any way you could, like, jiggle things around to make it work?’

It was the look of open appeal on her face that really got my sympathy going. ‘Well, maybe there is a way,’ I said, my mind still clawing through possible solutions as I spoke. According to my fostering agency’s rules, only the under-fives or same-sex siblings were allowed to share a room. Since Taylor and Reece fitted neither category, they needed a foster carer with two spare bedrooms.

‘And you’re sure you don’t mind?’ Maisie asked a few minutes later, her eyes, if not bright with relief, then at least a little less puffy than they had been.

‘Oh, it’s not really a problem,’ I answered, in a not quite convincing tone. I wanted to help and so had offered to convert our dining room into a temporary bedroom for myself. On a practical level it made sense – Taylor and Reece were already here and it was a bit late in the day to start hunting for a new placement for them – but the thought of dismantling the dining table and then dragging my own double bed downstairs wasn’t very appealing.

‘Cool,’ the social worker said, the thick wooden bangles on her wrists knocking together as she scratched the other side of her scalp. ‘We prefer children to stay at their own school if at all possible, and the only other carer matching their profile lives, like, forty miles away.’

‘Ah, I see,’ I said, my eyes narrowing. When social workers were desperate to place children, all sorts of cunning ruses came into play. I was beginning to wonder whether there really had been a mix-up over Taylor’s sex when the rise and fall of frenzied conversation drifted down the stairs. The noise brought my thoughts firmly back to the children and I decided to focus on the positives. With a nationwide shortage of foster carers, siblings were still sometimes separated. At least, in this instance, they could stay together. The base of my bed came in two halves so hopefully it wouldn’t be too heavy to lift and, compared with the upheaval Taylor and Reece were going through, moving a bit of furniture wasn’t too much of a hardship. ‘What’s their history?’ I asked, setting my suspicions aside. I knew that five-year-old Reece had made a disclosure to his teacher earlier that day, but that was about all.

Maisie blinked several times. She seemed to be struggling to summon the energy to speak. ‘So, as I said, I haven’t had a chance to go through their entire file yet but it seems that the children have been registered as “in need” for years. Their regular social worker is on long-term sick and I’ve only just inherited the case, but from what I can make out, a few incidents of domestic violence have been flagged up to us by police. Nothing too serious, but Dad is long-term unemployed and when you add Mum’s depression into the mix –’

Maisie’s sentence trailed off and I nodded, unsurprised. It was the spring of 2005 and although I had only been fostering for a couple of years, I had already noticed a common theme of domestic violence among the families of looked-after children. The violence was often accompanied by parental depression and substance abuse, a set of issues labelled by social workers as ‘the toxic trio’. When all three ‘markers’ were present, children were feared to be most at risk of severe harm.

‘Unfortunately, Taylor, the eldest, has been replicating the violence at school,’ Maisie said, snail-like. ‘I’m told that most of her classmates want nothing to do with her.’

‘Oh dear,’ I said, pressing my lips together. It was natural for Taylor to use her personal experiences as a template for relating to others. The poor girl was probably suffering as much as the children she was bullying, although I knew that was a view that could be unpopular, particularly with parents of the victim.

Maisie leaned back into the sofa and sipped from a can of Red Bull. It was her second since she’d arrived and I couldn’t help but wonder what she would be like without all that caffeine, if this was Maisie on fire. ‘As you probably know, Rosie, we have a duty of care to keep children within their own family if at all possible. It looks like all sorts of intervention therapies have been offered but the Fieldings have refused to engage with any of them.’

Longing to get upstairs and help the children to settle in, I reached for the nearest cushion, planted it on my lap and fiddled with the tassels. Being plucked from one life and planted in another one was a shock for anyone and the siblings were probably still reeling. Of course, there were some things that Maisie needed to tell me in private, but her drawl was agonisingly slow. ‘What did Reece disclose?’

‘So, Reece’s teacher noticed a red mark on his thigh as the class were changing for PE this morning. At first he made out that he’d been stung –’

I grimaced, amazed at the lengths children went to in defending parents who offered little protection in return.

‘I know, sweet, yeah? But when pressed, he admitted that his mother had slapped him. Mum’s insisting that it was just a little tap but there’s a mark, like,’ Maisie cupped her hands together in the shape of a rugby ball, ‘this big on his thigh.’

I sighed, my heart going out to him. It was March and the Easter holidays were only a few days away. There was often an influx of children coming into care when school holidays loomed – children seemed more able to cope with problems at home with the daily security of school to escape to but the prospect of losing that safety net sometimes drove them to reach out to their teachers for help. As a consequence, more disclosures were made in July and December than at any other time of the year.

‘School says that Mum’s really dedicated to the children so we’re leaving Bailey with her for the moment. There have been concerns about him since birth, mainly due to Mum’s mental health issues, but she’s on medication for her depression and things have been stable for a while, until this happened of course. We’re going to need to keep a close eye on things.’

‘Bailey?’

‘Oh, yeah, course, you don’t know that yet. He’s the youngest, fifteen months or so.’ Maisie took another sip of the energy drink. ‘We’re holding an emergency strategy meeting tomorrow to discuss what to do about him. For now, the parents have agreed to a Section 20 for Taylor and Reece.’

If children were removed from their parents under a Section 20, Voluntary Care Order, their parents retained full rights, at liberty to withdraw consent to foster care at any time. Reluctant families sometimes went along with a voluntary plan because they felt that they had more control over what happened to their children.

As Maisie finished her drink, I found myself wishing I had more space at home so that little Bailey could join us, should he need to come into care. Having recently attended a child protection course, I knew that on average over the past two years in the UK, more than one child a week lost their life at the hands of a violent parent. It seemed to me that social workers had a delicate balancing act on their hands in trying to ensure that the welfare of the child was paramount.

One of Douglas Adams’s dictums suddenly came to me. He said, ‘The fact that we live at the bottom of a deep gravity well, on the surface of a gas-covered planet going around a nuclear fireball 90 million miles away and think this to be normal is obviously some indication of how skewed our perspective tends to be.’ When a child is taken into care, the course of their life is sometimes changed for ever and I’ve often wondered how social workers set the bar of negligence objectively, in the absence of a definitive answer. I was just glad that the task of making such far-reaching decisions was outside of the remit of a foster carer’s role.

A loud scream from upstairs interrupted my thoughts. Maisie blinked and looked at me. I jumped to my feet and ran into the hall. ‘Are you all right up there?’ I called, taking the stairs two at a time.