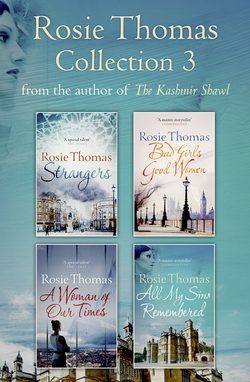

Читать книгу Rosie Thomas 4-Book Collection: Strangers, Bad Girls Good Women, A Woman of Our Times, All My Sins Remembered - Rosie Thomas - Страница 16

Eight

ОглавлениеFor a week, and then another week, Annie felt that she was being slowly drawn in half.

On the first morning after the day with Steve she came down to breakfast and found Martin already sitting at the breakfast table. His eyes were dark with shadows and the pain in his face made the guilt and regret twist inside her. Annie tried to say something, ‘Martin, listen to me, I don’t know …’ but he wouldn’t let her finish.

‘Not now,’ he said coldly.

He left his breakfast, picked up his briefcase and his coat, and walked out of the house without looking at her. Annie wanted to shout after him, or to put her head down on the table and cry until she couldn’t cry any more, but Thomas and Benjamin were standing in the doorway watching her.

‘Are you angry?’ Ben asked.

‘No, love.’ She tried to smile. ‘A little bit sad, today, that’s all.’

Their round faces reproached her.

After delivering them to school and to nursery, Annie came back and wandered in aimless circles through the house. She watched the silent telephone, willing Martin to ring so that she could begin to talk to him.

When at last it did ring it was Steve. Annie gripped the receiver as if the strength of her fingers could bring him closer.

‘Thank you for yesterday,’ Steve said. Annie could hear that he was smiling and the love and elation that she had felt yesterday lifted her heart. ‘It was one of the happiest days I have ever had.’

‘I was happy too.’

As always, Steve could hear more than the words. ‘Is something wrong?’

Rapidly Annie said, ‘It has to be at the expense of other people’s, our happiness, doesn’t it? At the expense of Martin’s, and the boys’.’

‘What happened?’ he persisted gently.

‘Nothing happened. Martin knows. Because he guessed, not because I had the courage to tell him. I came back without my shopping, you see, and that was supposed to be my alibi. Perhaps he’s seen it all along. We’ve known each other for a long time, Steve.’

‘I know that.’ The words were barely audible. At length he said, ‘He would have had to know some time, Annie. Isn’t it as well that it should be at the beginning?’ He was right, of course. But he hadn’t seen the hurt in Martin’s face last night, or the coldness this morning. Annie’s fingers wrapped even tighter around the receiver. Stop. She must stop feeling that Steve was to blame; that anyone was to blame. What had happened had happened, and now it must be faced. She took a breath, and tried to put a different, stronger note into her voice.

‘I’m sorry. I won’t pretend that what’s happening is anything but painful, or that it won’t go on being painful for a long time to come. Can you face that too, Steve?’

He answered her at once, as she had known that he would. ‘You know that I can.’

‘Yes.’

‘Annie, I’m here if you need me.’

She knew that too. She wanted to go to him, but she was fixed here, and she was afraid that the unfixing would damage them all more viciously than the bomb could ever have done.

‘Will you leave me for a few days to try to work things out here?’

‘Of course.’

After he had rung off Annie resumed her aimless circling of the house. She watched the slow clock until it was time to go to collect Ben, longing to have his innocent company. She set off briskly for the nursery, and all the way back she listened carefully to his recitation of the morning’s activities, trying to focus on him to the exclusion of everything else. When they were home again she cooked his lunch, laying out the carrots in the pattern he insisted on before he would even pretend to eat them, then sitting opposite him with a cup of coffee while he mashed the food up with his fork. Through the stream of Benjy’s questions and observations Annie kept hearing her own questions, and the silence that lay beyond them.

‘Why don’t you listen?’ Ben demanded crossly.

Annie felt the heat of unjustified irritation.

‘I can’t listen to everything all the time, Ben,’ she snapped. ‘I need to think sometimes.’

He looked at her, surprised, and then he stuck out his lower lip. ‘I need a cuddle,’ he said, acting, but Annie knew that at another level he wasn’t acting, but telling her the truth. She pushed her anger and sadness ashamedly back within herself.

‘Come and sit on my knee.’

He scrambled up triumphantly and she hugged him, then drew his plate of messy food across and spooned up a mouthful.

‘Come on, finish this and then we’ll watch your programme.’

Ben felt that he had won some undefined battle and so he willingly ate the rest of his lunch. Afterwards they sat on the sofa together, with Benjy’s head heavy against Annie’s chest. Annie stared unseeingly at the puppets on the screen and thought of the afternoon ahead of her, and the other afternoons of motherhood, and tried hopelessly to imagine them in another place, with Steve.

‘Let’s go to the park,’ she suggested when the programme finished. She found Benjy’s red suit and dragged his tricycle out of the tangle in the cupboard under the stairs. They set off, with Benjy trundling beside his mother, his face screwed up with concentration and the effort of pedalling.

The route was numbingly familiar, and the park itself. She followed Benjy from the swings to the roundabout, and stood at the foot of the slide while he hurtled down it. She felt too stiff and far-away to join in his game of hide-and-seek.

‘Not today,’ she told him. ‘Perhaps Daddy will bring you and Tom for a game tomorrow.’

What else would happen tomorrow, and the days afterwards? Annie felt cold. She saw that the sky was streaked with long fingers of cloud. The warmth of the misplaced spring was over, and tomorrow it would be as icy as January again. She walked around the knot of trees that stood in the middle of the park.

‘Come on, Ben. We’ll go and buy some bread for tea, and then we’ll get Thomas from school.’

Teatime came and went, and then the routine of the children’s play time, supper and baths and bedtime stories. When they were both asleep Annie came downstairs and poured herself a drink, looked at the dinner in the oven, and then sat down to wait. She knew that she was waiting for Martin, as she had been waiting all day. She waited for an hour, and then another half an hour, and then she took her portion of the dinner out of the oven and ate it, not tasting anything. She washed up the single plate and put it away, and sat down again in front of the television. She remembered that there was a basketful of mending waiting to be done so she fetched it and began to darn a hole in the elbow of one of Thomas’s school jerseys.

It was nearly half past ten when Martin came up the front path.

He had been sitting for hours in the corner of a bleak pub he had never been into before. Amidst the plastic and neon of brewery décor he had been thinking about himself and Annie, back over all the years that they had been together. He remembered her as they had been when they first met, and he recalled that he had fallen in love with her in a coffee bar, when she was still an awkward hybrid of outré student and shy schoolgirl. They had grown up together, from then. In two, perhaps three years? It seemed a short time to have accomplished so much, looking back at it with the speed of years’ passing now. But it had felt then as if they had for ever ahead of them. The memories went on, parading past him, while he stared unseeingly at his beer.

Was this what for ever added up to, then?

Everything that they had done together seemed much clearer, and precious, now. Because he was afraid that the end of it was coming?

He had never been afraid before, because he had been so sure of her. Even when there was Matthew, he had been sure.

Martin ducked his head over his unwanted beer, confronted by the spectre of arrogance.

Carefully, now, he made himself remember.

Matthew had materialized in the hot weeks of the summer before they were married. Martin had never even seen him, but Annie’s friend Louise, and other friends, had talked about him. Martin remembered that he had understood what was happening, but he had simply waited for her.

He had even asked her, Do I need to worry about it? And she had answered, No.

His certainty that she would come back seemed unbelievable now. Had he been so convinced that he was right about everything else, in those days?

He might have lost her, then.

Instead of losing her now.

For all the noise and distraction of the pub, Martin felt that he was hearing and seeing with sudden, perfect clarity.

Neither of them was fixed, nor defined as themselves at any point in time, not in that Soho coffee bar, nor on their wedding day, nor on the day of the bombing. They both went on changing, and they changed separately as well as together. They were not just the welded, coupled unit that he had silently asked her to confirm on the unhappy night of their dinner party. They were both of them at fault, perhaps, for forgetting that. They had seen each other fixed in a frame, as Martin-and-Annie, or as Benjy and Tom’s Mum and Dad, and when they slipped separately out of their fixed places, then they lost sight of one another.

How restless had Annie been, while he worked and concentrated on other things?

She was so good at giving all of them what they needed from her, he hadn’t troubled to look closely enough. It was only on Christmas Eve, when she had already gone, that he had really seen the neat evidence of her loving care. And then he had thought, Why didn’t I see before?

Or had Annie herself stopped seeing things, too?

Perhaps, Martin thought.

And if they were both at fault in their carelessness of one another, he had been wrong all the last weeks to heap the blame for what was happening on to the bombing.

The bomb was a senseless, terrible catalyst, nothing more.

The juke-box in the corner of the bar sent waves of meaningless noise washing around him.

If it hadn’t been Steve, then, it might have been someone else. Sooner or later.

Through the noise, Martin made himself follow the painful threads of thought. Now that it had happened. Think it. Now that his wife had fallen in love with someone else, what could he do?

With the end of his need to blame the bomb, Martin’s anger and bitterness against Steve drifted away too. There was nothing to be gained from going to find him, confronting him, as he had still half-imagined that he would do. To say what? Martin thought, and half-smiled at the picture that it conjured up. To ask for Annie back?

Martin sat for a long time, without moving, and then he picked up the pint glass and drained it.

There was nothing he could do. Nothing except wait, and by waiting hope to show her that he loved her, and wanted her, and needed her.

He stood up at last, stiff and with the bar music beating in his head. It was time to go home.

He drove back the familiar way, and parked the car outside the front gate. The lights were on in the downstairs rooms, and the dim glow of Benjy’s bedroom nightlight glowed against the drawn blind in the top window. The house looked just as it always did, and the sight made him long even more sharply for the old, ordinary times. If they came back again, he vowed to himself, he would keep them, rubbed bright, and never give them a chance to slip away.

He went up the path, and let himself in through the front door. Annie was sitting in the circle of light at one end of the old chesterfield. He saw the colour of her hair and the line of her cheek, and the mending lying in her lap.

They looked at each other without speaking, neither of them knowing what to say. Annie got up slowly and crossed the room to turn off the television news, and Martin stood rooted in the doorway watching the way that she bent down, straightened up again and walked away into the kitchen.

‘Would you like your dinner?’ she called back, tonelessly. ‘It’s rather dry, I’m afraid.’

‘It doesn’t matter. Yes, bring it in here, is that all right?’

A moment later she came in with a tray, a plate of food, ordinary things, like on any other night. Martin took it and began to eat, feeling the food settling on top of the gassy keg beer that he had drunk in the cheerless pub.

After a minute he said, ‘I thought we might talk, Annie.’

She was sitting across the room, her head bent, her hands folded on her darning. ‘Yes. I thought we might too,’ she whispered.

Martin groped, wondering where to start. ‘Tell me what happened.’

She looked at him then with a strange, almost supplicating expression. ‘You know what happened.’

He shook his head. ‘No, Annie. I want you to tell me, now. It’s time.’

She put her hands up to her eyes. He wanted to say, Don’t do that. Let me see your face, but he made himself keep quiet.

At last Annie said, ‘We were a couple, you and me, living here with our kids. It wasn’t anything extraordinary, was it? Nothing exotic, or passionate, or enthralling, but it was working. It was, wasn’t it?’

Martin nodded. ‘Yes,’ he said, very quietly. ‘It was working. Better than we deserved, perhaps.’

She looked across at him then, for a long moment, and then she nodded.

‘And then the bomb happened,’ Annie whispered. Martin saw her lift one shoulder, and let it drop again, a gesture of bewilderment, as though the bomb was something she had tried and failed to understand.

‘Tell me, Annie. You’ve never told me what it was like. What you felt.’

Annie stared at him, and he was afraid that she didn’t see him at all. And then she began to talk, in a low, unemphatic voice. ‘I don’t know how to tell you. I don’t know how to describe what it was like. It was dark, there was a terrible noise and then there was utter silence. I couldn’t move, and I could feel blood in my mouth, and dust and grit on my tongue. And there was pain everywhere.’ She shrugged again. ‘You know all that. What can I tell you?’

‘About fear.’

Annie thought about Tibby. She had come home from her hospice, to her husband and the roses, but she was too weak now to do her pruning. She’s seen you grow up. Seen her grandchildren. Yes. But what else was there? How many patient compromises? ‘I was afraid. I was … angry, too. I suppose it was anger. With the sense that everything was being cut short. That I wasn’t to be allowed to … finish. What I was doing.’

Martin looked round the room. There was a wicker basket full of Ben’s toys next to the hearth, a jar of daffodils on the mantelpiece amongst the clutter of china ornaments and candlesticks and children’s party invitations. ‘To finish what you were doing here, Annie? Was that it?’

‘Yes. Being a wife and mother.’ The words as they came out sounded strange to Annie, as if she had repeated them to herself so many times that their meaning had begun to elude her. ‘We were all right, weren’t we?’ she asked hastily. ‘The four of us.’

The past tense hit Martin squarely now. He looked at his wife in the lamplight, feeling the anger and bitterness of the past few days briefly renewed.

‘We were,’ he said. ‘We can be again, Annie, when all this is forgotten.’

As soon as he had spoken them, he knew that he had chosen the words badly. He shifted in his chair and the cutlery rattled on his plate. He glanced down and saw that the barely-touched food was congealing, and pushed it aside. Annie was still holding Thomas’s school jumper, with the darning wool unravelling on the rug beside her.

‘I can’t forget,’ she said, the words falling like clear drops of icy water.

‘Annie.’ He fought to keep his voice level. ‘You can, if you let yourself. It was a terrible, hideous thing to happen. The only thing you can do now is to be thankful that you survived, and forget everything else.’

They were circling around the truth now, watching each other, waiting.

‘If it were that easy,’ Annie whispered at last. ‘If only.’

Martin sat silently, feeling a vein throb in the angle of his jaw. The moment had come, and yet he could hope that it would somehow slip away again.

Annie went on, in the same low voice, looking down at the work in her lap. ‘Without Steve, I don’t think I could have survived. Steve made me hold on. He made me believe that we would get out. I’m not a very brave person. You know that. But he made me be.’

‘How?’ The word stuck in Martin’s throat, like a croak. He was remembering the day too; the cold outside the jagged store front, the corridors of the police station and the smoky tension inside the trailer, and the roughness of the smashed masonry as he pulled at it with the rescue workers.

‘We talked. We could just touch hands. We held on to one another and talked. Some of the time I didn’t know whether I was talking or thinking, but he heard anyway. And I listened to him talking. If you think you are going to die, it doesn’t matter what you say, does it?’

‘What did you say?’

‘We told each other about our lives. Everything, big things and little things.’

There was quiet again. Martin was imagining his wife, as he had done so often before, hurt in the darkness, with her hand held in the stranger’s. And her voice, a whisper like it was in the dark to him too, telling him the big things and the little things, only for him to hear.

‘Did you think about me, Annie?’ The petulance of the question struck at him at once and he thought, That’s how we all are. Annie dropped the darning and came across the room to him. She knelt on the rug in front of him with her head against his knees.

‘Of course.’

Martin said nothing.

‘I told him about you and the children and how I couldn’t bear the thought that our lives should be severed, abruptly, so violently, with the ends left fraying.’ He put out his hand then, tentatively, and stroked her hair. The ends of it were still frizzy from the awkward cut that had tried to repair the damage to it. ‘I told him about when we met, and after that. The ordinary things. The house, and the garden, and all the things we made and did together.’

Made. Did.

‘And he told you the same?’

‘Yes. Not quite such happy things.’

‘And after that?’ Martin asked gently, with his hand buried in her hair. He twisted his head so that he could see her face and then he saw that she was crying. There was a tear held at the corner of her eye, and the wet streak of another over her cheek. ‘At the end … it seemed like the end, you know … he was, he had become, more real and more important than anything else. He was all there was, then. He had come so close to me that … that I didn’t know any more where I ended and where he began.’

Martin’s hand tightened, just perceptibly, in Annie’s hair. He had looked down into the hole, under the arc lights, and he had seen Steve still lying there. His arm had been stretched out to where Annie had lain. There was a bitter taste in Martin’s mouth and throat. He was afraid of defeat. It had gone so far already, he thought, that they seemed utterly beyond his reach. With an effort at conviction he said, ‘But then you were rescued. It was over.’

Except that it wasn’t, not at all. He had sat beside her in the ambulance, and she had opened her eyes and looked at him with a mixture of bewilderment and disappointment.

When Annie didn’t answer he pushed on, trying in spite of himself to force the admission from her by seeming to misunderstand. ‘I know that you must have shared the shock and the reaction with him afterwards. No one else could possibly have come close to understanding what it was like down there. Of course you would have clung to each other then, while you were still recovering. Like a prop for one another.’

Annie raised her head and looked into his face. ‘Oh no,’ she said. There were still tears in her eyes, but there was a kind of reflected radiance as well. ‘It wasn’t that. It was the joy of it. The pure happiness of finding ourselves still alive. Can you understand?’

Martin counted back the days to that time. He had been preoccupied with the boys, with keeping the three of them going, and with containing his fears for Annie. There had been no opportunity for joy. The closest he had come to it was when the doctors had told him that Annie would live. He had gone down to see Steve, so that he would know too. Christmas Eve. He had sensed it, even then, Martin recalled. Pain and the fear of loss suddenly stabbed into him so that he almost doubled up.

‘Oh yes,’ he whispered, his voice so low that she could hardly hear him. ‘I think I can understand.’

I must tell him the truth, Annie thought. Now that we have come this far.

‘Everything looked so beautiful. So new, and precious, and exact. Steve saw it too. I think that it was because of that same feeing that … that we loved one another.’

And so he had heard her saying the words.

Suddenly his resolution to wait, and to hope, seemed futile. He couldn’t help the pointless anger that surged up in him, against the two of them, against every single thing that had happened since he had stared at the television news picture of the shattered store. He thought of Tom and Benjy upstairs and what the few impossible words would mean to them. And he knew that he loved his wife, and that he didn’t know how to live without her love in return.

‘Annie,’ he murmured. ‘Do you know what you’re saying? Do you know the hurt it will mean to all of us?’

Unable to keep still any longer he stumbled to his feet, knocking into a low table and sending his dinner tray skidding. Annie watched through stinging eyes the blobs of food fall on to the rug.

‘I know,’ she whispered. ‘Do you think I don’t know?’

‘What are you going to do?’

Annie thought of Tibby again, and the life that she had accepted for herself. Would her mother have made different choices if she had lived at a different time? Annie sensed again how precious life was, and how vital and miraculous its reopening had seemed to her in the hospital ward.

‘I don’t know,’ she said hopelessly. ‘I don’t know what to do. That’s the truth, Martin.’

He turned to the window, jerking the curtains aside so that he could stare into the street, then letting them fall again, a big man in a small space.

‘Are you going to bed with him?’

‘Once,’ Annie said.

There was a long silence after that. Martin sat wearily down again and Annie stayed motionless on the rug, her legs folded awkwardly beneath her, too numb to move.

At last Martin said in a softer voice, ‘People who have been together for as long as we have, what do they feel for each other? If you take away all the props of routine and familiarity and comfortable habit, I mean? They don’t love each other, do they? Not the kind of love you’re talking about.’

Annie thought of the wrenching intensity of her longing for Steve, and the crystalline happiness that she had known with him yesterday in the restaurant and in the shadow-barred flat.

‘No,’ she said painfully. ‘Not that kind.’

‘What is it then?’

She knew, and she searched for the words that wouldn’t devalue it, but Martin was quicker and blunter.

‘Friendship. Liking. We’re old friends, Annie. We’ve achieved that.’ He was unmoving, but she felt the anxiety inside him. ‘Oh, I still fancy you. You know that. That part of me belongs to you as comprehensively as everything else. But it’s not the first thing between us, is it? There’s more. We were solid. Perhaps we … didn’t look at one another, or hear one another, as carefully as we should have done. But we were happy, weren’t we?’ As he looked at her she heard the directness of his appeal. It can’t be different now. It can’t disappear, after so long.

And when she didn’t answer he persisted aloud, ‘Doesn’t it mean anything to you?’

Annie held out her hand and then, realizing the inadequacy of it, she let it fall again. ‘Of course it does. Martin, I’m still me. The years haven’t gone anywhere.’

But yet they were looking at each other across a divide. Here, now, so bitterly obvious amidst the shabby warmth of home. Annie knew that she couldn’t explain to him how the violence of what had happened had changed every cosy perspective, and how the same change of perspectives had jolted her into awareness, and then into love with another man.

It’s too late now, she thought.

‘What are you going to do?’ Martin asked her again.

She lifted her head. ‘I don’t know how to be without him.’ It was a simple offering of the truth, but she saw how the words cut into him. She wanted to close her eyes so that she need not look at what she saw in his face.

Martin might have shouted at her, let any of the ugly words that jumbled in his mouth come spilling out, or jumped up and snatched at her in a useless attempt to imprison her.

But with an effort of will he held himself still. When he could trust himself again he said very slowly, as if he had painstakingly learned the words in a strange language, ‘I don’t want to let you go. You’re my wife. Their mother.’

Love. Dues.

‘I don’t know what to say.’ He looked down at his fists, clenching and unclenching them, the knuckles white and then red. ‘Just that I’m here, Annie. If you … when … if you do decide. I want you to think, that’s all. Think what it means. Think quickly.’

All he could focus on now was getting away, out of this room, to hunch over the gaping hole that her words had left. I don’t know how to be without him. He stood up awkwardly, almost falling. And then he went out, closing the door behind him.

Annie heard him going upstairs, and then his footsteps overhead, the door of the spare room closing against her. She sat staring ahead of her, breathless with the pain that she had caused to both of them. Then she drew up her knees and, with her head resting against them, she tried to do what he had asked her.

The two weeks were like a time out of somebody else’s life. In the mornings when Annie woke up she had forgotten for a second or two and she felt warm and easy. But then the recollection came back and she had to climb up and out into the cold again, and live through a day that wasn’t her own any more, until it was time to sleep again.

To live without it made her more vividly aware that friendship was truly what she had shared with Martin. Even Benjamin recognized it when it was no longer there. He came early one morning and stood in the bedroom door in his blue pyjamas, seeing Annie alone in the wide bed.

‘Aren’t you friends with Daddy any more?’ he asked, and Annie couldn’t answer him. She held out her arms instead, and even though he came she felt him holding himself a little away from her, as if he didn’t know where to commit his loyalty.

That hurt her more than anything else had done.

And she carried her sadness with her to Steve, although she tried hard not to.

‘I’m sorry,’ she said. ‘I told you at the beginning. Our happiness makes unhappiness everywhere else.’

Steve was gentle and firm. He sat beside her on his deep black sofa and put his arms around her. He made her talk and he listened and he held her until her frozen shell of anxiety and guilt began to melt. Then he took her into his bedroom and made her lie down beside him. He knew when to coax and when to be insistent, and he knew when to let Annie herself take the initiative. Her need for him surprised her. She sat astride him and the shock of pleasure as he drove upwards made her arch her body and then lean forwards, enclosing him more tightly, until their mouths met and they rolled over, locked together, driving one another further on, and then further still.

‘You’re very sexy, my Annie,’ he told her.

‘I know,’ she said, unblushingly. ‘You’ve shown me that.’

In the face of everything, still, they were happy in their short hours together. When they had finished making love they would get up and go out together. Steve took her to odd, offbeat places. They ate lunch at a Jewish restaurant in the East End, they went to a workshop production of a short, savagely funny, feminist play, and to an organ recital at a Wren church in the City. From the way that strangers stared at her in these places Annie knew that she looked unlike the other women. She was glowing and crackling and alive in a way that she had never expected that she would be again. She took the hours of happiness and held tenaciously on to them, because without them there was no justification for the coldness and blackness that spread through all the other hours like a disease.

Although they were quite different from the penniless days that she had shared long ago with Matthew, her short outings with Steve often reminded her of them. She felt the same exhilaration, and the recklessness was all the more pronounced because of the weight of reason and responsibility that settled around her on the way home again.

And at other times, when she looked at Steve sitting across from her in a restaurant, or standing in the aisle of the Wren church reading the inscription on a marble slab, she could hardly believe that this handsome, faintly ruthless-looking man was anything to do with her at all. She would draw in her breath then, shivering, but Steve with his ability to read her thoughts would reach for her hand, and say something that drew her close to him again, and then the moment would be past. When it was time for Benjy to come home, or at the hour she had agreed with Audrey or whichever of his friends’ mothers had invited him to play, Annie left Steve and went back to collect him.

The glow of happiness faded at once and the dull, enduring pain of being pulled in half took hold of her all over again.

In between the terrible shuttling to and fro, whenever she could, Annie went to see her mother. She was still at home in the old house, but she had grown so weak that she could hardly move from her bed to the wing chair in the corner of the living room next to the fire. Jim and Annie and a home help, with a visiting nurse, looked after her between them as best they could. Tibby still wanted to be dressed in her familiar heathery tweed skirts and woollen cardigans, and on most mornings Annie went to do it after she had taken the boys to school and nursery. The clothes when she took them out of the mahogany wardrobe or the tidy drawers still smelt of her mother’s lavender scent, but they seemed huge when she slipped them over Tibby’s brittle bones.

‘The fit on this skirt is terrible,’ Tibby would murmur as she pulled at a gaping waistband. ‘It’s a good one, too. They don’t make clothes like they used to, darling. I’d like the pink cardigan with this. It’s better, don’t you think?’

As she helped her up and fastened her buttons, pinned the loose folds of fabric and arranged her mother’s thin hair, Annie found that she could hardly answer. Her mother had been the centre and the heart of this big house, and now it was as if a draught had blown her into a corner of it, depositing her in a chair like a cobweb or the dust she had battled against for so many years.

Annie settled her into her place. Tibby’s hands on her arms looked almost transparent.

‘Shall I turn you round today so that you can see into the garden?’ she asked.

Tibby thought for a moment. Annie saw her glance at the photographs on the low table beside her. Tibby’s wedding picture. Annie and her brother as children, Annie’s own wedding, her brother’s wife and children. Thomas and Benjamin, Tom with his top front teeth missing.

‘Yes, I think so,’ Tibby said.

Annie turned her chair and they looked through the French windows into the garden. It was the first week of April. Tibby’s early daffodils were already falling, but the forsythia hedge behind them was a sheet of gold. Tulips in bud like green spears had come up in the half-moon beside the window, and the prunus showed the first delicate edges of pink blossom. Annie saw that the lawn needed mowing. It must have sprung up in the warm sunshine of March.

‘I’ll ask Martin to come and cut the grass for Jim,’ she murmured.

Tibby nodded; but she didn’t begin to talk about attending to her roses, as she would have done only a week or so ago. She looked at her flowers, and at the blaze of the resplendent hedge.

‘I think the spring has always been the best time,’ she said, almost to herself. ‘I think I’ve always preferred the promise to the reality. Of summer, of course. The brighter colours, you know. Too bright, sometimes. Not like this pale green and gold.’

Go on, Annie implored her silently. Please, won’t you talk about it to me? She wanted to kneel down in front of her mother and rest her head in her lap. Talk about the promise, and the reality, won’t you? Because we haven’t got very long, Tibby. We both know that we haven’t, and there is such a lot to say.

She was suddenly overwhelmed by her own need to tell her mother everything.

Gently she asked her, ‘How do you feel today?’

If Tibby could admit the truth. If they could just begin, she thought.

Tibby’s back straightened in her chair. She didn’t take her eyes off the gold of the garden, but she said, ‘A little better, I think.’

And so they wouldn’t admit that she was going to die, and that it might happen at any time, and that Tibby would be gone, leaving only the dust and the big house and the echoes of their talk about the roses.

Annie bent her head for a moment, so that Tibby would not see her sadness showing in her face. If that was how Tibby wanted it to be, of course Annie must let it be. She straightened up again and asked brightly, ‘Can I bring anything in here before I go?’

‘The magazine and the book from the table beside my bed, darling, if you wouldn’t mind. Jim will be back from the shops soon.’

Jim always went out to buy the few things that they needed, every morning, at nine-fifteen exactly. As Annie walked back through the shadowy house she saw that the tallboys and the grandfather clock were dusty. But as Tibby had stopped worrying about her roses, she seemed to care less for her house now. She was withdrawing into herself, the battle lost. Had it been worth the fight at all? Annie thought savagely. Was anyone’s fight worth it?

She gave her mother the book and the magazine, kissed the top of her head and fled blindly from the house.

At the end of the second week, Annie knew that she was lost.

Her bearings were gone, and she was groping through days that seemed increasingly to belong to someone who she didn’t know or understand. To compensate for her sense of being adrift she held on as firmly as she could to the familiar, mechanical things. She ironed the clothes, concentrating fiercely on folding the shirts into neat, symmetrical piles. In the evenings Martin often didn’t come home until very late, so Annie filled the hours by cooking casseroles for the freezer. She ladled the food into foil cartons and labelled and dated them in small, neat handwriting that looked quite unlike her own. But the little, domestic satisfaction that she usually gained from such things turned itself against Annie now. She thought bitterly that she was lining her family nest with food and clothes before abandoning it herself.

She caught herself wondering whether, after all, she might be just a little mad. School holiday time came, and the number of hours that she could find to spend with Steve dwindled almost to none.

‘Do you think,’ he had asked her on the telephone, ‘I could meet your children soon?’ She had stood looking across the kitchen at them until his voice in her ear had prompted her, ‘Are you still there?’

‘Yes. Yes, of course, you must. What shall we do?’

They had arranged it. It would be on Friday, for a hamburger lunch and then a trip to the cinema to see a film that Tom had been agitating about for weeks and weeks.

Annie put off from day to day the moment of telling the children about the expedition. She told herself that she would make it sound very casual, an almost impromptu adventure with a friend. Then Friday morning came. It was one of those days when Martin had got up and gone to work very early, and Tom and Benjy had hardly seen him. They had been asleep the night before when he came in.

‘What shall we do today, Mum?’ Thomas asked. He had cleared the breakfast dishes for her without protest, and he had spent a patient quarter of an hour doing Lego with Benjy while Annie swept the kitchen and hovered the living room. ‘Can we ring Timothy and ask him to come round?’

Annie wound up the flex of the vacuum cleaner very carefully.

‘I thought we might go on a trip today,’ she said. ‘We could go for a hamburger, and then to see that film of yours.’

Their eyes met over Benjamin’s head. Annie saw the wariness at once. He’s been waiting for something, she thought. He may not know what it is, or even that he is waiting and dreading something. But it’s there, just the same. He can feel it in the house. See it in our faces.

‘Just us?’ Tom asked her.

‘A friend of mine would like to come along too.’ She tried to keep her voice steady and warm.

‘Who?’ The small voice was suspicious.

‘His name is Steve.’

‘We don’t know him,’ Tom said at once, with utter finality.

‘Not yet,’ Annie agreed. ‘But I hope that you will like him.’

Thomas lowered his eyes. He turned back to the box of Lego and rummaged through it, making ostentatious noise.

‘We should go quite soon, I think,’ Annie continued. ‘We’ll have to go into town on the tube.’

Thomas sat back on his heels, but with his head still bent over his model. He turned it to and fro, looking carefully at it.

‘I don’t want to go,’ he said.

Benjy’s eyes went from one to the other. ‘I don’t want to go,’ he echoed. ‘Not at all.’

They had set themselves solidly against her, by instinct, closing their ranks against the stranger their mother tried to push forward as a friend. Annie was convinced that their refusal was absolute.

They’re eight years and three years old, she tried to tell herself. You’re adult, and their mother. You can persuade them. Bribe them, force them.

For Steve’s sake? For her own? Not for their own, she was certain of that.

She went across and knelt beside Tom. ‘Why don’t you want to go?’ she asked gently. ‘You’ve been telling me for weeks that you must see this film.’

She had thought, not carefully enough, that their eagerness for it would carry all of them through the first meeting. And after that, then it would be easier.

Thomas raised his eyes again, and the adult awareness in them made her feel cold.

What am I doing to my kids? she thought.

‘I want to see the film with Dad,’ he told her clearly. ‘It’s about space. Dad likes things like that.’

‘Me too,’ Benjamin said. ‘I want to see the film with Dad.’

Annie took a breath, trying to smile. ‘Okay,’ she said. ‘We’ll leave the film for Dad. Shall we just go and have lunch with Steve?’

Thomas flung the Lego back into the box. His face went dull red, as it always did when he was upset. And then he shouted at her, ‘I don’t want to. I don’t like Steve. I won’t go. Benjy won’t either.’

Annie was shaking. It wasn’t any use insisting to Tom, You don’t know Steve. He did, of course. From half-heard fragments of his parents’ angry talk, from the unhappy silence of the house, and from his own fearful unconscious, Tom had made up his own picture of Steve. He knew the threat was close, and he had responded to it in the only way he knew.

As she knelt there Annie saw, with perfect clarity, how it would be.

There would be months, probably years, of times like this one. As she watched Thomas’s red face and Benjamin’s bewildered one she felt the pain of their divided loyalties, the sharpening of their premature awareness. There would be the ugly battles over their custody. Martin would fight her, lent strength by his bitterness, she was certain of that. She knew, as vividly as if she had already lived through them, what the bleak Sunday visits with the boys would be like, what they would be like for Martin, whichever of them won whichever portion of their children’s lives.

Was her own happiness worth that? This strange, exotic happiness since the bomb, that seemed increasingly to belong to another woman altogether? What was Steve’s happiness worth? She saw his face, every line of it clear, and she knew that she loved him, and the hurt stabbed like a knife inside her.

At last she stood up, stiffly, with pain in her chest and across her shoulders.

‘All right,’ she said softly. ‘That’s all right. You needn’t come, if you don’t want to. I have to go, because I promised I would. I’ll call Audrey, and ask her if she can come and look after you, just for a little while.’

The boys sat in silence while she telephoned.

‘Audrey?’ Annie said. ‘I know I’ve asked you too many favours lately. This is the last, I promise.’

‘You want me to come in to the boys?’

Audrey, Annie thought, with her grown-up daughters and her grandchildren, and her morose husband. Has Audrey got what she wants? Is she like Tibby? Annie’s face felt hot, and her eyes were bright and hard.

‘Just for an hour or two, this morning.’

‘Of course I will, my love. I’d be glad to. Gets me out of the house, doesn’t it?’ While they waited for her, the three of them sat in a circle round the Lego box, pretending that they were playing together. It wasn’t until he heard Audrey at the gate that Tom said hastily, anxiously, ‘Is it all right, Mum?’

‘I’ll make it all right,’ she promised him. Whatever it costs.

Audrey was in the hallway. ‘Only me,’ she called out to them, as she always did. Annie went over and put the kettle on. ‘Hello, Audrey. Shall I make you a cup of tea before I go? It’s kind of you to help out yet again.’

Audrey looked at her, shrewd under her perennial headscarf. ‘You go on, love. Do what you like, while you still can.’

Annie turned away with the kettle heavy in her hand. ‘This is the last time,’ she whispered.

When Audrey was furnished with her tea in her special china cup and saucer, Annie put her coat on. She didn’t stop to look at herself, and Audrey had to call after her, ‘Your collar’s all caught up at the back.’ She came after her and straightened it, motherly. ‘Are you all right, my pet?’

‘Yes,’ Annie said quickly. ‘Yes, I’m fine.’ From the doorway she looked at Benjy and Tom. They were absorbed in their game now. She had told them that she would make everything right, hadn’t she?

‘Bye,’ she said. ‘I’ll be back as soon as I can.’

‘Bye,’ Thomas said absently, not looking up. Ben didn’t make any response at all. Only Audrey said again, ‘You do what you want, Annie. Don’t worry about us.’

She almost laughed at that. The sound of it, beginning in her head, was hideous.

Annie had no memory of how she reached Steve’s flat. She was aware that it took a long time, and that she was afraid that her resolve would desert her. But at last she was riding up in the mirrored lift. She stared down at her feet rather than confront her own reflection.

When he opened the door she looked straight into his eyes.

‘I can’t do it,’ Annie said.

He took her arm, led her inside and closed the door. The black sofa in front of her was too close, too comfortable. Annie broke awkwardly away and sat on an upright chair.

‘What can’t you do?’ Steve asked her.

Nothing, she wanted to say. There’s nothing I can’t do, so long as I’m with you. Her vacillating spirit shamed her. Outside, a long way beneath the windows, Annie could hear the traffic. The sound was incongruous high up in the enclosed room.

‘I can’t leave them,’ Annie said. The words hurt, as if they were pulled out of her like splinters.

Steve turned his face away. After a moment he stood up and went to the window. He looked at the skeins of cars and taxis down below.

‘Why now, Annie? Why have you decided this now?’ His voice was cold with disappointment. Annie thought of the two weeks that had just gone by, and the weeks before that, all the way back to Christmas. It wasn’t a decision made just this morning, arbitrary, as Steve must see it. It was simply, at last, the recognition of the bald truth that had confronted her always.

‘I am a coward,’ she whispered.

Steve snapped round to face her then. His black eyebrows were drawn together in anger with her.

‘You are nothing of the kind. Don’t use that as an excuse.’

She saw his hurt, and it made her own seem trivial.

‘I’ll tell you what happened,’ she said. ‘The hamburger lunch and film that we’d planned, remember? I offered them to my kids this morning. As casually, lightly as I could. And their faces closed up. They knew at once that here was the threat to them. You and me. Do you know what Thomas said?’

Steve listened motionless as she told him.

Annie said, ‘And I knew then that I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t even begin. Whether it’s weakness or cowardice, Steve, I couldn’t contemplate it being like that, for years, perhaps for ever, until they are grown up.’ Her smile twisted. ‘If it hadn’t been now. If it had been in ten years’ time. Or ten years ago.’

Except that it had happened ten years ago, and she had taken the easy option then. I don’t deserve even as much as I have got, Annie thought sadly.

‘Do you think your children will appreciate that so much has been sacrificed for them?’

She smiled again, crookedly. No one with children of his own, no one who understood the everyday sacrifices of parenthood, would have asked that. ‘I don’t suppose so.’

‘And Martin?’

Annie thought. ‘Martin and I were friends. Perhaps we can put some of that back together, for the kids.’

Steve made a last attempt. He put aside all the angry complex of feelings and he told her the truth.

‘I love you, Annie. You haven’t given me a chance.’

She wanted to run to him. She ached to lay her head against his heart, to rest in him and to acknowledge the truth. But Annie held her head up. Now that she had come so far, she couldn’t waver any more.

‘I love you too. There never was a chance for us.’

They looked at one another then, and they were drawn helplessly across the room. Annie put her hands out and he took them in his. She knew the touch of them in every mood now, and he seemed suddenly so physically warm and real that the idea of being without him was impossible. Annie had promised herself that she would leave before she started to cry, but the tears came now and she could do nothing about them.

She looked up at Steve through the heat of them and she said, uselessly, ‘I’m sorry. I would give anything for it to be different.’

With a sudden, fierce gesture Steve rubbed the tears off her cheek with the palm of his hand and kissed the red mark that was left. He kissed her eyelids, and the corners of her eyes and mouth, and then her mouth itself. For a moment, a long moment that threatened to tear her all over again, Annie succumbed. She felt that after all there was a possibility, a possibility within her reach. But then it was gone again, and she was left to confront the same truth.

She felt a sob gathering inside her but she forced it down again.

‘I’ve got to go home now,’ she said. ‘Tom and Benjy are … waiting for me.’

Steve’s arms dropped heavily to his sides. ‘Don’t let me keep you from them.’

She couldn’t blame him for the bitterness, Annie thought. She turned, uncertainly, and went to the door. She held on to the handle for a moment with her head bent, on the point of turning to him again. She felt that he was waiting and she told herself, No. Do it quickly now. She opened the door and closed it again behind her. And then she was alone in the empty corridor.

Steve stood unmoving for a moment, watching the door. He could still see her quite clearly, as clearly as his reason told him that she was really gone. At last he shook his head, painfully, as if he were trying to clear it. He went to the window and leaned his forehead against the glass. It reminded him of the hospital, and the day room windows high above the side street.

‘Annie?’ he said aloud.

He watched until he saw her come out into the street, her shoulders shrugged defensively into her coat. She crossed the busy road, and then she was swallowed up into the crowd.

He didn’t know how long he stood there, watching the oblivious surge of people. The telephone rang on the black table and he picked it up.

‘I’m sorry to bother you at home, Steve. Bob needs a couple of words about Boneys. Can I put him through?’

It was Bob Jefferies’ secretary. Steve frowned, looking at his table. It was littered with story-boards, reports and notes. Dogfood, he thought.

‘Put him on, Sandra. I’m not busy.’

Steve went through the problem about the pet-food film with his partner, his mind working, just like it always did. When Bob had run off Steve held on to the receiver, weighing it, like a weapon. Then he stabbed out another number. His own secretary answered.

‘Jenny? I’m going to be in full-time again from Monday. I’ve had enough time off. Fix up what needs to be done, will you?’

Jenny made a silent face across the office at the word-processor operator. She knew that tone of Steve’s.

‘Yes, of course. There are some messages for you. Do you want them now?’

‘What messages?’

Even though it was impossible, Steve hoped for a brief moment. Jenny recited them, ordinary, routine requests and reminders. Then she added, ‘Vicky Shaw has called once or twice. She rang again this morning, just to see if you were in.’

It took Steve a second to remember, it seemed so long ago. He frowned again, with the sense of something unwelcome, and then he looked around at the grey flat. Through the open bedroom door he could just see the corner of the bed.

He thought of Annie as she had been in bed, laughing, with her mouth close to his. With her eyes closed, crying out. Asleep, with her hair spread out over his arm. He understood, then, that she was gone. With the understanding he hated the empty flat and the silence, and he was afraid of his solitude.

‘Steve?’

‘Yeah.’ He was gathering up the sheaves of paper with his free hand, cramming them into his expensive black briefcase. ‘Listen, Jenny, if Vicky calls again tell her that I’m on my way in to the office now. I’ll be ringing her later this afternoon. See you in thirty minutes.’

Jenny hung up. ‘Here we go,’ she sighed to the word-processor girl.

Steve finished packing up his work. He thought of his car down in the underground car park, the familiar drive, his desk in the urban-chic company office. The work would be waiting for him. Boneys, fruit-juice, washing powder, whatever it was that needed to be shown and sold. Lunch, dinner with Vicky, bed and sleep and work again. And so it would go on, just the same. As if nothing had changed, instead of everything.

Steve picked up his loaded briefcase.

‘There never was a chance for us?’ he echoed aloud. ‘You’re wrong, Annie. We had all the chances that there could be.’

The phone rang again. ‘I’m on my way,’ he shouted at it. ‘What more do you want?’

He went out of the flat and left it, still ringing.

Annie told Martin.

‘I went to see Steve today.’

She was clearing the plates from the pine table after dinner and stacking them on the draining board. Martin would wash them up after they had watched the television news. How odd it was, she thought. They had reached the remotest point of their life together, so far apart that she didn’t know how they would come back again. But they still went padding through the familiar routines, almost silent, barely looking at each other. Like the heavy, neutered tomcats next door. The comparison made Annie want to laugh, incongruously, but she turned from the sink and saw Martin watching her. He looked wary, and exhausted. She went to him then, and put her hand on his arm.

‘I … told him that I was going to stay here. With you and the boys. I didn’t want to go, because … I saw how it would be.’ How inadequate the words were. ‘I’m sorry.’

Martin nodded.

He should have felt a rush of relief, a sense of the oppressive weight that had darkened the house lifting, to let in the light and air. But he felt nothing. He looked at Annie, trying to see behind her face, knowing that he couldn’t because he hadn’t been able to for so many weeks.

‘It doesn’t matter who was right,’ he said at last. ‘Can you live with it, Annie?’

‘Yes,’ she answered him, because she had to. ‘I can live with it.’

And that was all they said.

They were old enough, and they understood one another well enough, Annie reflected, not to expect there to be anything more. There would be no reconciliation in a shower of coloured light. Instead there would be the small tokens of renewal, scraps, cautiously offered one by one. In time they would be stitched up again into a serviceable patchwork, and that was as much as they could hope for.

That night Martin came back and slept beside her. It would take time, of course, before he put his arms round her again. That first night Annie lay quietly on her side of the bed, trying to take simple comfort from the warmth of him next to her. She made herself suppress the voice inside her that cried out for Steve.

But the truth was, as Annie had been half-afraid when she had answered Martin, that she couldn’t live with it. She had made her decision as honourably as she could, and she did her best to keep to it. But the days began to pile up into weeks, and Annie felt that she was building a house without windows. It was clean and polished, and there was food on the table and clean clothes in the chests, but there was no light in it anywhere. It was claustrophobic; the air tasted as if she had breathed it in and out a dozen times, just as she had done the things that she was doing a hundred or a thousand times before. She would have done them gladly if she had felt that their repetition was taking her anywhere – but she was uncertain that she would ever draw close to her husband, or that Martin would ever let her come any nearer. They were polite, and considerate, but they were not partners, or friends.

And Annie missed Steve. She missed him every day, in all the intervals of it. She heard the cadences of his voice in the radio-announcer’s, she glimpsed his head in a crowd and walked faster to keep him in sight, and then suffered the disappointment when the stranger turned and she saw that he was nothing like Steve at all. She found herself thinking about him as she carried baskets of wet washing out to peg on the clothes line, and as she made the plodding walk with Benjy to pick up Tom from afternoon school. She wondered whether Steve thought about her too.

Two or three times, despising herself for her capitulation, she picked up the telephone and dialled his number. The first time, when Martin was away for a two-day business trip, she sat at her kitchen table for an hour, looking at the telephone, before she went to it. She picked out the number with a clumsy finger and listened to the ringing in her ear. There were only two rings, not long enough for him to have reached the phone … there was a click, and Annie heard his voice, and there was a painful beat of pleasure before she realized that it was only a recorded message. He repeated the number, and said his name. He sounded so close, and yet she couldn’t reach him.

With her heart thumping guiltily, Annie listened to the conversational message. I’m sorry, I can’t take your call. If you’ll leave your name and number. After the tone, she hung up. She went back to her place and sat down, her hands loose in her lap, staring into nothing.

A week went by, and she called again. The message was the same, and it gave her the same eerie feeling of closeness.

I must be mad, she thought. What comfort is there in listening to his recorded voice? But there was a kind of comfort, and she rang again, a third time, as guilty and as furtive as an addict.

April went, and May, and June came. The early roses came into bud and then flowered. Tibby was still alive, but she couldn’t see them.

She had been taken into the hospice again, and Annie knew that she wouldn’t be coming home. But for her mother’s sake she still went regularly to the old house, to dust the polished furniture and fill the vases and wind up the mantelpiece clocks. Annie didn’t think that her father would do it. He had retreated from the house, apparently in relief. He lived in the kitchen, strewing it with spent matches from his pipe. It was Annie who cut the roses and brought them in to arrange in Tibby’s silver bowls. She listened to the echo of her own footsteps on the parquet, and remembered the house as it had been when she was a child. She had had the same memories after the bomb. Herself, in a green dress with white ribbons in her hair, running to Tibby. She had hurt herself, and her mother had taken her out of the sun and into the shadowy living room to comfort her.

As she stood in the squares of light that the sun spilt on the wooden floor Annie had a renewed sense of time, ribbons of continuity linking Tibby and her husband, Martin and herself, Annie’s children, children’s children. In the silent house, with the memories of her own childhood close to her, it was the thought of the boys that comforted her. She could hear them calling, as she had heard them in the stifling darkness of the bomb wreckage.

Mum, look at me.

Running in the garden, at home. As she had run in this garden, calling out to Tibby.

Love for all of them warmed her, family love, and all the complicated knots of anxiety, and pride, and relief that they were somehow still together, caught at her and held her. With the sound of their voices in her head Annie remembered the happiness of chains of ordinary days that she had shared with her sons, all the way to yesterday, the last link in the chain.

She had taken them to Hampstead Heath, to the little travelling funfair that arrived two or three times a year and spread its gaudy, temporary camp over a bare patch of hill. For years they had been visiting it whenever it appeared, usually with Martin too, but yesterday he had claimed some drawings to finish and so Annie had driven the boys over on her own. She had felt the dead weight of loneliness as she negotiated the traffic, but when they had left the car behind and the boys were scrambling ahead of her Annie’s spirits lifted like the strings of flags flying from the sideshow tents. They loved the fair, all of them.

Annie caught up with the boys who were poised breathlessly at the outer ring of caravans and generators and pulsing machines.

‘What can we go on, Mum?’

She took one hand in each of hers and swung them round.

‘Everything.’

They plunged into the crowds and noise together. The tinny music and the barkers’ shouts, the smell of candyfloss and frying onions and the whirl of colours swallowed the three of them effortlessly. Within the circle of the fair Annie felt suddenly no older than Thomas and Ben. The fierce pleasure of childhood excitement touched her, and it was intensified by the added, subtle pleasure of her adult capacity to indulge her children, and share their indulgence.

With Tom pulling ahead they stumbled to the giant Waltzers at the centre of the fairground. The rumble of cars spinning on the wooden track drowned out even the blaring music. The riders screamed joyfully from their seats as they were swept past.

Annie clutched at responsibility for long enough to shout to Tom, ‘Benjy’s not old enough for this!’

Tom turned for a second, his hands on his hips, the sudden, living replica of his father. ‘He is. We can look after him. One on each side.’

‘I am old enough,’ said Benjy stoutly.

‘All right, then.’ They beamed at one another, colluding.

The huge machine was winding down and the riders’ faces, laughing, sprang out of the blur as the cars swung slower up and down the undulating slopes. As soon as an empty car rolled past, Thomas was off up the steps. He squirmed inside it and fended off the crowds who swarmed around it.

‘No, this is ours. Come on, Mum, Benjy.’ They ran up the steep steps after him, hand in hand, and jumped into the padded tub. Annie wedged Benjy tightly between Tom and herself and drew down the chrome hoop for them to hold on to.

‘Here we go,’ Tom yelled, leaning with the car as it began to turn to spin it faster.

Faster, and then faster again, and then to the point where centrifugal force pressed them helplessly against the chair back and tore the shouts from their throats. Annie drew her arm tighter around them, feeling their thin shoulders rigid with delighted fear. Benjy’s face was three amazed circles, and Tom’s smile was pinned right across his face. They spun faster and the world blurred into a solid wall, and the boy who took their money came balancing along the spinning edge and whirled their car faster on its axis, grinning at Annie and then pursing his lips to whistle as the wind blew her skirt up over her thighs.

‘Oh boy.’ Thomas was shouting with joy and Benjy managed a faint, tiny echo.

Hold on to them, Annie thought. Hold on. Forever.

And then they were slowing down again, gasping and laughing, thrilled with their daring as the world resolved itself again into its separate parts.

‘Wasn’t it great?’ Thomas demanded and Benjy screamed, ‘Wasn’t I brave?’

‘Oh, it was,’ Annie said weakly. ‘And you were, both of you. How could I have gone on that without you?’

They struggled off with rubber legs, the ground’s immobility strange under their feet.

‘What now?’ asked Thomas.

Seeing his face, Annie wanted to take hold of his delight and keep it, so that it could never fade. So that nothing would fade ever again. But she couldn’t do any more than put her hand on his shoulder, just for a moment, to link herself to him.

‘Something gentle,’ she pleaded.

‘I know the one you like,’ he said triumphantly. He took her hand now, and stretched out the other to Ben. ‘Come on. Don’t anyone get lost.’

He threaded them through the crowds to the huge mirrored roundabout whose steam organ ground out a pleasing, wheezy waltz. Annie looked up at it. The ornate lettering around the canopy spelled out, as it slowly revolved, The Prancers. H.W. Peacock’s Pride.

‘The hobby horses,’ she murmured. ‘I do like the hobby horses best.’

‘They’re pretty slow,’ sniffed Thomas. But he enjoyed the ride, whooping from his horse’s slippery back and hanging on to the gilded barley-sugar pole, as much as Annie and Ben did.

After the hobby horses they rode under the musty green hood of the Caterpillar, and on the Dodgems with their blue sparks and thundering crashes, and on the Octopus, and all the others even down to the toddlers’ roundabouts at the outer edges of the magic circle where Benjy swooped on the fire engine and rang the bell furiously as he trundled around, while Thomas squeezed himself into a racing car or helicopter and scowled at Annie every time he came past.

When they had ridden every roundabout they plunged into the sideshows, from the bleeping electronic games that all three of them adored, to the tattered old stalls where Annie and Tom vied with each other to throw darts at wobbly boards or shoot the pingpong balls off nodding ducks. Benjy was furiously partisan, pulling at Annie’s arm and shouting, ‘Come on, Mummy. Why don’t you win?’

Annie laughed and threw down her twisted rifle.

‘It’s no good, Ben. I’m not nearly as good as Thomas is.’

‘Here you are, baby,’ Tom snorted, thrusting the orange fur teddy bear that he had won at Benjy. ‘Is this what you wanted?’

‘I just wanted Mum to win,’ Benjy retorted. ‘I don’t want her to be sad.’

‘I won’t be sad,’ she promised him. The outside reached in, just for a moment, between the caravans and flags. ‘I won’t be sad. Let’s go and see the funny mirrors.’

They lined up in the narrow booth and paraded to and fro in front of the distorting mirrors. The images of the three of them leapt back and forth too, telescoping from spindly giants to squat barrels with grinning turnip faces.

The boys roared and gurgled with laugher, clutching at one another for support. ‘Look at Mum! Look at her legs!’

‘And her teeth. Like an old horse’s.’

Annie laughed much more at their abandoned enjoyment than at the gaping figures. Adults never laugh like this, like children do, she thought. Not giving themselves up to it.

In the end she had to pull them away from the mirrors to make room for the press of people coming in behind them. She hauled them out into the sunshine, blinking and still snorting with laughter.

‘Are you hungry?’

‘I’m so hungry.’

‘And me.’

They picnicked on hot dogs oozing with fried onions and ketchup, and Annie bought them huge puffballs of candyfloss that collapsed in sticky pink ridges over their beaming faces.

‘You’re letting us have all the bad things, Ma.’

‘Just for today,’ she said severely.

When they had finished the repellent meal they turned to her again.

‘Is it time for the Big Wheel now?’

By unspoken agreement, they had saved it until last. They crossed the trampled grass now and joined the queue in its spidery shadow. Benjy tilted his head backwards to peer up at the height of it.

‘I was too little last time.’

Annie crouched beside him, straightening his jacket, an excuse to hold on to him.

‘You’re big enough now. After the Waltzers you’re big enough for anything.’

They grew so quickly. They were here and now, together. Wasn’t that enough? As they inched forward in the queue the cold fingers from outside reached in to clutch at Annie. She tried to shake them off, and hold on to the day’s hermetic happiness.

It was enough, because it would have to be.

At last their turn came. The attendant let them in through the little metal gate and they climbed into the little swinging car, the boys on either side of Annie. The safety bar was latched into place and the wheel turned, sweeping them upwards and backwards. As they soared up they felt the wind in their faces, scented with grass and woodsmoke up here, above the packed crowds and the hot-dog stalls. When they reached the highest point the wheel stopped turning and they hung in the stillness, rocking in windy, empty space. Ben gave a little squeak of fear and burrowed against her, and Annie held her arm around him, hiding his eyes with her hand. But Tom leaned forward, his face turning sombre.

Beneath them spread all the tumult of the fairground, suddenly dwarfed. Beyond was the undulating green of treetops, rolling downhill, and the houses edging the heath, a jumble of slate and stone. London stretched out beyond that, pale blue and grey and ochre.

‘It’s beautiful,’ Tom said.

Annie felt tears in her eyes, and ducked her head. She put her arm round him and drew him close to her.

‘It is,’ she whispered. ‘It’s very beautiful.’

They sat silent in the rocking chair, and looked at it. In that moment of stillness Annie felt that she loved her children more than she had ever done before.

And then the wheel jerked and began to turn again, sweeping them down towards the ground.

After the ride they stood in the shadow of the wheel again.

‘What shall we do now?’

Annie took out her purse. She opened it and showed them the recesses. ‘Look. We’ve spent all the money. I’ve got just enough to buy you a balloon each to take home.’

They peered into the purse, needing to be convinced. Then they sighed with reluctant satisfaction. They agreed with the logic of staying until every penny was spent, and then of having to go home. On the way out of the noisy, joyful circle they chose a pair of red and silver helium balloons, decorated with Superman for Tom and Spiderman for Benjy. And then with the balloons tugging and twisting above them they plodded back down the hill to the car.

When they were inside it, insulated from the people streaming by, Tom turned to Annie.

‘That was so good,’ he said simply. ‘I can’t think of anyone else’s Mum who would have gone on everything, like you. Well, I suppose they might have done. But they wouldn’t have enjoyed it, like you did.’

‘I did enjoy it,’ Annie said. ‘Thank you.’

Benjy scrambled forward and laid his face briefly against her neck, stickily, his own form of thanks.

Then Annie started the car up and turned towards home. Martin would be waiting, and the ache of Steve’s absence would be waiting for her too.

It was not many days after the funfair that Tibby’s doctor took Annie and her father aside. ‘If you were going to ask her son to come home and see her,’ he said, ‘I think it should be done quite soon.’

Annie’s brother was working as an engineer in the Middle East. Annie and Jim put through the call at once, as they had agreed with Phillip that they would.

‘I’ll be home within forty-eight hours,’ Phillip said.

Tibby lay in her hospice room, surrounded by flowers that Annie brought in from her garden.

‘There must be a fine show this year,’ she said politely, when Annie had arranged them.

Annie sat by the bed, watching her mother’s transparent face. Tibby was usually awake, but she rarely spoke. When she did speak, it was about small things; the doctors or one of the other patients, or the food they brought her that she couldn’t eat. She didn’t even talk about her grandchildren any more. Annie knew that her mother’s world had shrunk to the dimensions of her hospital bed.

It was hard for Tibby to be dignified under such circumstances, even though the staff who looked after her did all that was possible to control her pain. But she clung tenaciously to the silence that she had maintained about her illness. She didn’t talk any more about getting better, but she wouldn’t admit the fact of approaching death either. In the beginning Annie had seen the refusal as a kind of graceful courage. But as the months had passed her frustration had grown. She felt the silence now like a cold glass wall between her mother and herself.

She reached for Tibby’s hand and held it. It felt as dry and weightless as a dead leaf. As she sat in the quiet, flower-scented room Annie was realizing that she didn’t want her mother to die without acknowledging the truth, even if it was only by a word. As if to acknowledge it would be to tell her daughter, It’s all right. I know what’s happening to me. I can bear it, and so can you.

I’m just like Benjy and Tom, Annie thought. I want my mother’s reassurance, even now that she’s dying.

Love, dues. The ribbons of continuity, again and again.

Annie glanced up and saw that Tibby was looking sideways at her. Her glance was clear, appraising, full of her mother’s own intelligence and understanding.

Annie thought briefly, At last.

But then Tibby’s head fell back against her pillows. ‘I’m tired,’ she said. ‘I think I’ll go to sleep now, darling.’

Annie stood up and leant over to kiss her cheek. ‘I’ll come in again at the same time tomorrow,’ she promised, as she always did.

Phillip arrived thirty-six hours later. Annie met him at Heathrow, and drove him straight to the hospice.

‘They don’t know how much longer,’ she told him. ‘I’m glad you’re here, Phil.’

She glanced at him as she drove. Phillip was fair, like her, but he was losing his hair and his skin was reddened by the sun. He looked exactly what he was, a successful engineer just back from overseas. Annie and her brother had never been close, even as children. Phillip had always been the brisk, practical one, while Annie was slow and dreamy. He had been his father’s son, always, while Annie and her mother had shared a friendship, she understood now, that had its roots in their strong similarity.

But she was genuinely glad and relieved to see Phillip now. She felt some of the weight of her anxiety shifting on to the shoulders of his lightweight suit.

The family bond, she thought wryly. Always there.

When she stopped at a red light Phillip put his arm round her.

‘I’m sorry I haven’t been here. Are you all right, Anne? You don’t look as though you’ve recovered properly yourself.’

The car rolled forward again.

‘How could you be here? There would have been nothing you could do, anyway. And I’m fine, thanks.’

‘It hasn’t been much of a year for you, has it?’

Annie watched the road intently. ‘It has had its ups and downs.’

There was nothing else she could say to Phillip, however searchingly he stared at her. Not to this broad, red-faced man who had stepped briefly out of an unknown world, even if he was her brother.

They reached the hospice, and went upstairs to Tibby’s room. Jim had been sitting by her bed, and he stood up now and hugged his son. Tibby opened her eyes.

‘Hello, Mum,’ Phillip said. ‘I’ve got some leave, so here I am.’

Tibby looked at him, unmoving. For an instant Annie glimpsed the same clear awareness in her face, and it heartened her. Then her mother smiled faintly, and lifted her shrunken hand.

‘Hello, darling. Come and sit here by me.’

Annie watched Phillip sit down, and take hold of Tibby’s hand.

Her sense of relief intensified, making her feel light, almost weightless. Of course Tibby knew that she was dying. Her way of confronting it was natural, for Tibby. Admiration of her mother’s bravery blazed up inside Annie.

‘I’ll call in later,’ she whispered, and she left Tibby with her husband and son.

It was early evening when she drove back again and the houses and shops and parks glowed in the rich, buttery sunlight. Annie parked her car in the hospice visitors’ park and walked up the steps past tubs of shimmering violet and blue and white petunias.

Tibby’s room was shadowy behind drawn curtains. Annie thought at first that her mother was asleep, but she turned her head at the click of the door.

‘Did I wake you?’ Annie murmured.

Tibby shook her head. ‘No. I was thinking. Remembering things. I’m very good at remembering now. All kinds of things that I thought I had forgotten for ever.’

Annie smiled at her. She knew just how it was. The fragments of confetti, precious fragments.

‘Shall I open the curtains a little?’ she asked. ‘The light outside is beautiful.’

Tibby shook her head. ‘It’s comfortable like this.’

Tibby didn’t want to see the light any more, Annie knew that. Her world had shrunk to the bed, and the faces around it. She nodded, with the tears behind her eyes, and for a moment they were quiet in the dim room.

Then Tibby said, ‘Thank you for calling Phillip home.’ Her eyes had been half-closed but they opened wide now, piercing Annie. ‘I know what it means.’ She smiled, and then she added, as if Annie were a child again, and she was comforting her after a childish misunderstanding, very softly, ‘It’s all right.’

The mixture of pain, and relief, and love that flooded through Annie was almost too much for her. She sat with her head bent, holding Tibby’s hand folded between her own. They were silent again. Annie thought that Tibby was pursuing her own memories, piecing together the confetti pictures as she had done herself with Steve.

But Tibby said suddenly, in a clear voice that startled her, ‘Is it something between you and Martin? Is that why you are unhappy?’

Denials, placatory phrases and soothing half-truths followed one another through Annie’s mind. She had opened her mouth to say, Of course not, we’re very happy, but she raised her head and met her mother’s eyes.

I was the one who wanted the truth, she thought.

‘I fell in love with someone else,’ she said simply. ‘A stranger.’

‘When?’

‘After the bomb. We were there together.’

Tibby nodded. ‘I guessed that,’ she said. The maternal intuition took Annie back to girlhood all over again. She tightened her fingers on her mother’s. Don’t go, Tibby. I’ll miss you too much.

‘What are you going to do?’

Annie looked at her hopelessly. ‘Nothing. What is there to do?’

Suddenly she could see how bright Tibby’s eyes were in the dimness. The corners of her mouth drew down, an economical gesture of impatience, disappointment, all that she had the strength for. Annie knew that she had given the wrong answer.

There was a long, long pause before Tibby spoke again. ‘I did nothing,’ she said. ‘Don’t make the same mistakes. Don’t.’ The last word was no more than a soft, exhaled breath. The confession hurt her. Tibby closed her eyes, exhausted.

Annie saw it all, the sharp outlines of the story, even though she would never know the details. Tibby and Jim had failed each other somehow, in the course of the years. Perhaps there had been another man. Perhaps a path of a different kind had offered itself. Annie remembered her mother’s wedding picture, with Tibby in her little tilted hat, her lips vividly painted. Whatever had happened, the two of them had stayed together. For her own sake, perhaps, and Phillip’s. Tibby had taken on the protection of the house and the big corner garden, and Jim the routines that commanded his days.

Annie felt the sadness of it, drifting and settling, as silent and as endless as the dust on her mother’s furniture. What reason was there?

Don’t make the same mistakes.

But no one’s mistakes could be the same. They were all different, and the permutations of their mistakes stretched on into infinity.

Annie lifted her mother’s hand, feeling the bones move under the skin. Some things were right. So many of Tibby’s. Those were the ones to hold on to.

‘You’ve got us,’ she whispered. ‘I love you, Tibby.’

Tibby smiled, without opening her eyes. Her head was heavy against the pillow.

‘I know,’ she said.

Annie stayed with her until she was sure that she was asleep. Then she laid her hand gently back on the covers and went out into the light again. The brightness made her blink and she stood for a moment on the steps, watching the intensity of it on the frilled trumpets of the petunias. Then Annie climbed into her car and drove back through the streets to Martin, and the boys who were waiting for her under the rucked-up shelter of their bedcovers.

Tibby died the same night, peacefully, in her sleep.