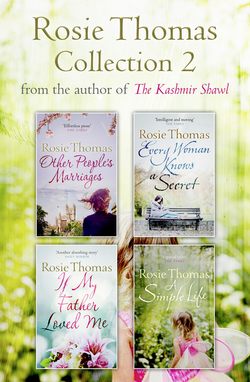

Читать книгу Rosie Thomas 4-Book Collection: Other People’s Marriages, Every Woman Knows a Secret, If My Father Loved Me, A Simple Life - Rosie Thomas - Страница 9

Two

ОглавлениеJanice Frost and Marcelle Wickham were the first to notice Nina. They were in the big supermarket and in the distance, as if the perspective lines of the shelves held her vividly spotlit just before the vanishing point, they saw a tall, thin woman in a long black skirt. Her red hair was pinned up in an untidy nest on the top of her head and her mouth was painted the same colour, over-bright in her white face.

‘Who is that?’ Janice wondered. Janice knew everybody interesting in town, at least by sight.

Marcelle looked. As they watched, the woman moved away with her empty wire basket and disappeared.

Marcelle lifted a giant box of detergent into her trolley and squared it up alongside the cereals and tetrapacks of apple juice.

‘Haven’t a clue. Some visitor, I suppose. Crazy hair.’

They worked their way methodically up one side of the aisle and down the other, and then up and down the succeeding avenues as they always did, but they didn’t catch sight of the red-haired woman again.

Nina paid for her purchases, sandwiching them precisely on the conveyor belt between two metal bars labelled ‘Next Customer Please’, all the time disliking the frugal appearance of the single portions of meat, vegetables and fish. She loved to cook, but could find no pleasure in it as a solitary pursuit.

She had no car in Grafton. She had sold the Alfa Romeo that Richard had bought her, along with his Bentley coupé, in the grief-fuelled rejection of their possessions immediately after his death. To take her back into the centre of town there was a round-nosed shuttle bus that reminded her of a child’s toy. She squeezed inside it with the pensioners and young mothers with their folding pushchairs, and balanced her light load of shopping against her hip. The bus swung out of the car park immediately in front of Janice and Marcelle in Janice’s Volvo.

The next person to see Nina was Andrew Frost, Janice’s husband. Andrew did recognize her.

Nina had been working. She was painting the face of a tiger peering out of the leaves of a jungle, part of an alphabet book. For a long morning she had been able to lose herself behind the creature’s striped mask and in the green depths of the foliage. She worked steadily, loading the tip of her tiny brush with points of gold and emerald and jade, but then she looked up and saw blue sky over her head.

It was time to eat lunch, but she could find no enthusiasm for preparing even the simplest meal. Instead she took a bright red jacket off a peg and went out to walk on the green.

Andrew had left his offices intending to go to an organ recital in the cathedral. He was walking over the grass towards the west porch, pleased with the prospect of an hour’s music and freedom from meetings and telephones. He saw a red-haired woman in a crimson jacket crossing diagonally in front of him, and knew at once who she was. She had worn a costume in the same shade of red to play Beatrice.

He quickened his pace to intercept her.

‘It’s Nina Strange, isn’t it?’

Nina stopped. She turned to see a square man with thinning fair hair, a man in a suit who carried a raincoat even though the sky was blue.

‘You don’t remember me,’ the man said equably.

A thread of recollection snagged in her head.

‘Yes, yes I do. Wait a minute …’

‘“When I said I would die a bachelor, I did not think I should live till I were married.”’

‘Oh, God, I do remember! It’s Andrew, isn’t it?’

‘Andrew Frost. Benedick to your elegant Beatrice.’

‘Don’t try to remind me of how long ago.’ Nina held out her hand and shook his. She was laughing and her face was suddenly bright. She remembered the plump teenaged boy who had played opposite her in the joint Shakespeare production of their respective grammar schools.

‘You were very good. I was dreadful,’ he said.

‘No, you weren’t. And your calves were excellent in Elizabethan stockings.’

Andrew beamed at her. ‘I was going to hear some music, but why don’t we go across to the Eagle instead? Have you had lunch?’

Nina hesitated.

Small fragments of memory were rapidly coalescing and strengthening, swimming into focus in front of her like the images in a developing Polaroid snapshot. She could see the boy now, inside this grown man, and as she looked harder at him the boy’s features grew more pronounced until it seemed that it was the man who was the memory. The sight of the young face brought back to her the long hours of rehearsal in the school hall smelling of floor polish and musty costumes, the miniature and tearful dramas of adolescence, the voices of teachers and friends. It was disorientating to find herself standing on the green again, almost within the shade of the mulberry tree, but clothed in the body of a middle-aged woman instead of a schoolgirl’s.

‘I can’t. I really shouldn’t today. I’m working. I’ve only come out for five minutes’ fresh air.’

It was three days since she had spoken more than half a dozen words to anyone. She didn’t want the questions to start in the saloon bar of the Eagle. She was afraid that if she was given a chance she would let too many words come pouring out, and she didn’t want Andrew Frost to hear them.

‘Working? Are you staying in Grafton?’ He was standing with one hand in his pocket, the other hitching his raincoat over his shoulder. He was friendly and relaxed, no more than naturally curious.

‘I … I’ve come back to live. I bought a house, in Dean’s Row.’

Andrew pursed his mouth in a soundless whistle, ‘Did you, now?’

Nina asked quickly, ‘What about you? Did you follow on from Benedick and find your Beatrice?’ There was a gold wedding ring on his finger.

‘I married Janice Bell. Do you remember her?’ Nina shook her head.

‘Perhaps she came after your time.’

Nina wanted to move on. It was reassuring to have made this small contact, but she needed a space to adjust Andrew Frost in her mind. She pointed to the cathedral porch.

‘You can still get into the recital. Perhaps we can have lunch together another day?’

Andrew took a business card out of his wallet and wrote on the reverse. When he handed it to her she read the inscription ‘Frost Ransome, Consulting Engineers’, with Andrew’s name beneath followed by a string of letters. Nina pursed her lips to whistle too, mimicking his gesture.

The boy’s face was swallowed up again now by the fleshier man’s.

‘We’re having a party, at home, on Thursday evening. That’s the address. It’s Hallowe’en,’ he added, as if some explanation was necessary.

‘So it is.’

‘Spook costumes are not obligatory. But come, won’t you? Janice’ll like to meet you.’

‘Thank you. I’m not sure … I’ll try.’

‘Who do you know in Grafton these days?’ He was looking at her with his head on one side.

‘Not a soul.’

‘Then you must come. No argument.’ He reached out and shook her hand, concluding a deal. ‘Thursday.’

Nina would have prevaricated, but he was already walking away towards the cathedral. She went back to her desk and bent over her tiger painting with renewed attention.

She had not intended to go. She had thought that when Thursday came she would telephone Andrew’s office and leave an apology with his secretary. But when the morning and half the afternoon passed and she had still not made the call, she recognized with surprise that her real intention must be the opposite.

Nina finished her painting and carefully masked it with an overlay before placing it with the others in a drawer of the plan chest. She was pleased with the work she had done so far. The new studio suited her, and she was making faster progress than she and the publishers had estimated. She would go to the Frosts’ party, because there was no reason for not doing so. Quickly, as if to forestall her own second thoughts, she looked in the telephone directory for the number of a minicab company and ordered a car to collect her at eight-thirty.

*

Marcelle Wickham was a professional cook, and she was spending the afternoon at Janice’s to help her to make the food for the party. The two of them worked comfortably, to a background murmur of radio music.

Janice admired the rows of tiny golden croustades as they came out of the oven, taking one hot and popping it into her mouth.

‘Delicious. You are a doll to do this, Mar, do you know that?’

‘Pass me the piping bag.’ Marcelle wiped her hands on her apron. The logo of the cookery school at which she worked as a demonstrator was printed on the bib.

‘I like doing it. I like the’ – she gestured in the air with her fingers – ‘the pinching and the peeling, all the textures, mixing them together.’ Her face relaxed into a smile, elastic, like dough. ‘I love it, really. I always have, from when I was a little girl. And I love seeing the finished thing, and the pleasure it gives.’

Janice sighed. ‘You’re lucky.’

Marcelle filled the piping bag with aubergine purée and began to squeeze immaculate rosettes into pastry shells.

‘I read somewhere that cooking is one of the three human activities that occupy the exact middle ground between nature and art.’

‘What are the others?’

‘Gardening.’

‘Ha.’ Janice glanced out of her kitchen window. Her large, unkempt garden functioned mainly as a football ground for her two boys.

‘And sex.’

‘Ha, ha!’

They glanced at one another over the baking sheets. There was the wry, unspoken acknowledgement, of the kind familiar to long-married women who know each other well, of the humdrum realities of tired husbands, demanding children and sex that becomes a matter of domestic habit rather than passion. They also silently affirmed that within their own bodies, and notwithstanding everything else that might contradict them, they still felt like girls, springy and full of sap.

‘Perhaps I’ll concentrate on flower arranging,’ Janice said, and they both laughed.

‘So exactly who is coming tonight?’

‘The usual faces. Roses, Cleggs, Ransomes.’

These, with the Frosts and the Wickhams, were the five families. They ate and relaxed and gossiped in each other’s houses, and made weekend arrangements for their children to play together because all of them, except for the Roses, had young children and in various permutations they made up pairs or groups for games and sport, and went on summer holidays together. There were other couples and other families amongst their friends, of course, and Janice listed some of their names now, but these five were the inner circle.

‘Five points of a glittering star in the Grafton firmament,’ Darcy Clegg had called them once, half-drunk and half-serious, as he surveyed them gathered around his dining table. They had drunk a toast to themselves and to the Grafton Star in Darcy’s good wine.

‘That’s about fifty altogether, isn’t it? No one you don’t know, I think,’ Janice concluded. ‘Except some woman Andrew was at school with, who he bumped into on the green the other day.’

‘Oh well, there’s always Jimmy.’

Again there was the flicker of amused acknowledgement between them. All the wives liked Jimmy Rose. He danced with them, and flirted at parties. It was his special talent to make each of them feel that whilst he paid an obligatory amount of attention to the others, she was the special one, the one who really interested him.

‘What are you wearing?’

Janice made a face. ‘My best black. It’s witchy enough. And I’ve got too fat for anything else. Oh, God. Look at the time. They’ll be in in half an hour.’

The children arrived at four o’clock. Vicky Ransome, the wife of Andrew’s partner, had offered to do the school run even though it was not her day and she was eight and a half months pregnant. Janice’s boys ran yelling into the kitchen with Vicky and Marcelle’s children following behind them. The Frost boys were eleven and nine. They were large, sturdy children with their father’s fair hair and square chin. The elder one, Toby, whipped a Hallowe’en mask from inside his school blazer and covered his face with it. He turned on Marcelle’s seven-year-old with a banshee wail, and the little girl screamed and ran to hide behind her mother.

‘Don’t be such a baby, Daisy,’ Marcelle ordered. ‘It’s only Toby. Hello, Vicky.’

The boys ran out again, taking Marcelle’s son with them. Daisy and Vicky’s daughter clung around the mothers, weepily sheltering from the boys. Vicky’s second daughter, only four, was asleep outside in the car.

Vicky leaned wearily against the worktop. ‘They fought all the way home, girls against boys, boys definitely winning.’

Janice lifted a stool behind her. ‘You poor thing. Here. And there’s some tea.’

The boys thundered back again, clamouring for food. Janice dispensed drinks, bread and honey, slices of chocolate cake. The noise and skirmishing temporarily subsided and the mothers’ conversation went on in its practised way over the children’s heads.

‘How are you feeling?’ Marcelle asked Vicky.

‘Like John Hurt in Alien, if you really want to know.’

‘Oh, gross,’ Toby Frost shouted from across the kitchen table.

Vicky shifted her weight uncomfortably on the stool. She spread the palms of her hands on either side of her stomach and massaged her bulk. Her hair was clipped back from her face with a barrette, and her cheeks were shiny and pink. With one hand she reached out for a slice of the chocolate cake and went on rubbing with the other.

‘And I can’t stop eating. Crisps, chocolate, Jaffa cakes. Rice pudding out of a tin. I’m huge. It wasn’t like this with either of the others.’

‘Not much longer,’ Janice consoled her.

‘And never again, amen,’ Vicky prayed.

The relative peace of the tea interval did not last long. Once the food had been demolished there was a clamour of demands for help with pumpkin lanterns and ghost costumes. William Frost had already spiked his hair up into green points with luminous gel, and Daisy Wickham, her fears momentarily forgotten, was squirming into a skeleton suit. Andrew had promised to take his own children and the Wickhams trick-or-treating for an hour before the adults’ party.

‘I’ll leave you to it,’ Vicky said, bearing away her six-year-old Mary who screamed at being removed from the fun. ‘See you later. I’ll be wearing my white thing. You can distinguish me from Moby Dick by my scarlet face.’

After she had gone Marcelle frowned. ‘Vicky’s not so good this time, is she?’

Janice was preoccupied. ‘She’ll be okay once it’s born. Look at the time. Toby, will you get out of here? Please God Andrew gets himself home soon.’

‘Shouldn’t bank on it,’ Marcelle said cheerfully.

Nina chose her clothes with care. She was not sure what Andrew had meant when he said that fancy dress was not obligatory. Did that mean that only half of the guests would be trailing about in white bedsheets?

In the end she opted for an asymmetric column of greenish silk wound about with pointed panels of sea-coloured chiffon. The dress had cost the earth, and when she first wore it Richard had remarked that it made her look like a Victorian medium rigged out for a seance.

And as she remembered it, the exact cadence of his voice came back to her as clearly as if he were standing at her shoulder.

She stood still for a moment and rested her face against the cold glass of her bathroom mirror. Then, when the spasm had passed, she managed to fix her attention on the application of paint to her eyes. At eight-thirty exactly her car arrived.

The Frosts’ house was at the end of a quiet cul-de-sac on the good, rural side of the town. From what was visible of the dark frame to the blazing windows, Nina registered that the house was large, pre-war, with a jumble of gables and tall chimneys. There were pumpkin lanterns grinning on the gateposts, and a bunch of silver helium balloons rattling and whipping in the wind. Nina’s high heels crunched on the gravel.

When the door was opened to her she had a momentary impression of a babel of noise, crashing music, and a horde of over-excited children running up and down the stairs. Something in a red suit, with horns and a tail, whisked out of her sight. She stopped dead, and then focused on the woman who had opened the door. She was dark, with well-defined eyes and a wide mouth, and was dressed in a good black frock that probably hid some excess weight. On her head she wore a wire-brimmed witch’s hat with the point tipsily drooping to one side. She looked hard at Nina, and then smiled.

‘You must be Andrew’s friend? Nina, isn’t it? Come on in, and welcome.’

The door opened hospitably wide. Once she was inside, Nina realized that Andrew’s wife had spoken in a pleasant, low voice. The noise wasn’t nearly as loud as it had at first seemed, and there were only four children visible. Nina understood that it was simply that she had undergone a week’s solitude, and was unused to any noise except her own thoughts.

‘I’m Janice,’ Janice said.

‘Nina Cort. Used to be Nina Strange, when Andrew knew me. I’m sorry I haven’t come in fancy dress.’

Janice waved her glass. ‘Your dress is beautiful. I only put this hat on at the last minute, and Andrew is defiantly wearing his penguin suit.’ Her mouth pouted in disparagement, but her eyes revealed her pride in him. ‘Come on, come with me and I’ll get you a drink and introduce you to everyone.’

Nina followed her down the hallway towards the back of the house. The man in the devil suit was sitting at the foot of the stairs, and he glanced up at her as she passed. His eyebrows rose in triangular points.

Andrew Frost kissed her in welcome, and gave her a glass of champagne. Nina drank it gratefully, quickly, and accepted another.

She was launched into a succession of conversations, but felt as if she was bobbing on a rip tide of unfamiliar faces. The effect was surreal, heightened by the fact that some of the faces were ghoulishly made up, swaying above ghost costumes or witches’ robes, while others sprouted conventionally painted from cocktail dresses or naked and pink from the necks of dress shirts constricted by black ties. The man in the devil suit prowled the room, flicking his arrow-headed tail. A delectably pretty girl of about eighteen threaded through the crowd offering a tray of canapés and the devil man capered behind her, grinning.

Nina loved parties, but for a long time Richard had been there for her like a buoy to which she could hitch herself if she found she was drifting away too fast. Now she was cut loose, and the swirl of the current alarmed her.

The room was hot, and confusingly scented with a dozen different perfumes. There was a woman in a long white dress, majestically pregnant, and another, younger, in a shimmering outfit that exposed two-thirds of her creamy white breasts. There was a dark man with a beaky profile, two more men who talked about a golf tournament, a thin woman with a reflective expression who did not smile when Nina was introduced to her.

Nina finished her third glass of champagne. She had been talking very quickly, animatedly, moving her hands like fish and laughing too readily. She realized that she had been afraid of coming alone to this house of strangers. Now she was only afraid that she might be going to faint.

She wanted to hold on to someone. She wanted it so badly that her hands balled into fists.

She held up her head and walked slowly through the chattering groups. It was only a party, like a hundred others she had been to, perhaps a little rowdier because these people seemed to know each other so well. Grafton was a small place.

The kitchen was ahead of her, more brightly lit than the other rooms. There were people gathered in here too, only fewer of them. In the middle of them was Janice, without her hat, and another woman in an apron. They were laying out more food on a long table.

‘Can I help?’ Nina asked politely.

‘No, but come and talk,’ Janice answered at once. ‘Have you met Marcelle? This is Marcelle Wickham.’

The woman in the apron held out her hand and Nina shook it. It was small and warm and dry, like a child’s.

‘Hi. We saw you in the supermarket, Jan and I. Did she tell you?’

‘I’ve hardly had a chance to speak to her. I’m sorry, Nina. I’m just going to tell everyone that the food’s ready …’ Janice pushed her hair off her damp forehead with the back of her hand.

‘We wondered who you were,’ Marcelle explained.

Nina’s hands moved again. ‘Just me.’

‘Who, exactly?’ a man’s voice asked behind her.

‘Look after her for me, Darcy, will you?’ Janice begged as she hurried past. The man inclined his head obediently and passed a high stool to Nina. She sat down in the place that Vicky Ransome had occupied earlier.

‘I’m Darcy Clegg,’ the man said.

He was older than most of the Frosts’ other friends, perhaps in his early fifties. He had a well-fleshed, handsome face and grey eyes with heavy lids. He was wearing what looked like a Gaultier dinner jacket, conventionally and expensively cut except for a line of black fringing across the back and over the upper arms and breast, like a cowboy suit. He had a glass and his own bottle of whisky at one elbow.

‘That is a spectacular dress,’ Darcy Clegg drawled.

Nina liked men who noticed clothes, and bothered to comment on them.

‘How long have you been in Grafton?’ he asked.

Sitting upright, in the kitchen light, Nina sensed that the inquisition was about to begin.

She explained, as bloodlessly as she could, who she was and what she was doing. Darcy listened, turning his whisky glass round and round in his fingers, occasionally taking a long gulp. This new woman with her green eyes and extraordinary hair was interesting, although evidently as neurotic as hell. There was some strange, strong current emanating from her. Her fingers kept moving as if she wanted to grab hold of something. Darcy wondered what she would be like in bed. One of those hot-skinned, clawing women who emitted throaty cries. Nothing like Hannah.

‘And has your husband come down here with you?’ Darcy asked. Nina still wore Richard’s rings.

‘He died nearly six months ago. Of an asthma attack, at our house in the country. He was there alone.’

‘I’m very sorry,’ Darcy murmured. A recollection stirred in him, troubling although he couldn’t identify a reason for it, and he made a half-hearted effort to pursue it. Who had told him a similar tragic story? When the connection continued to elude him Darcy shrugged it away. In many trivial ways he was a lazy man, although he was tenacious in others.

‘What about you? Do you live in Grafton?’ Nina felt that it was her turn.

‘Outside. About three miles away, towards Pendlebury.’

‘And are you married?’

Darcy turned his grey eyes on her and he smiled, acknow-ledging the question. ‘Yes. My wife’s name is Hannah. In the silver décolleté.’

Of course. The luscious blonde with the bare breasts. Nina was beginning to fit the couples together, pairing the unfamiliar smiling faces two by two.

‘And the girl handing round the canapés is Cathy, one of my daughters. By my first wife.’ The smile again, showing his good teeth. Darcy Clegg was attractive, Nina was now fully aware. Politely he filled her glass and they began to talk about how Grafton had changed since Nina’s school days.

More guests filtered into the kitchen, following the scent of Marcelle’s cooking, and the noise swelled around Nina once more.

*

Gordon Ransome brought his wife a plate of food and a knife and fork wrapped in a napkin. Vicky was sitting in a low chair in a corner of the drawing room, where a side lamp shone on the top of her head. He glanced down at her for an instant and saw the vulnerable pallor of her scalp where her hair parted. He had not noticed before that it grew in exactly the same way as their daughters’, and he felt a spasm of exasperated tenderness. She had collapsed into a chair that was too low for her, and she would need help to struggle to her feet again. The voluminous white folds of her dress emphasized her bulge.

When she looked up he saw also that there were dark circles under her eyes and her face was small, and sharp- pointed.

Vicky took the plate and hoisted herself awkwardly upright, wincing as she did so. She began to eat, ravenously, even though she knew that after half a dozen mouthfuls the burning would begin under her breastbone. She was made more uncomfortable by Gordon looming impatiently above her.

‘We mustn’t be too late,’ she said. Alice had a cough and their sitter was only fifteen.

‘I don’t want to go yet,’ Gordon snapped. ‘We’ve only just got here.’ He swung away with his hands in his pockets, feeling immediately ashamed of his bad temper. But he often felt that his helplessly pregnant wife and his little daughters were like tender obstacles that he had to skirt around, day by day, walking softly lest somebody should start to cry. He loved them all, but they took so much of his care.

Darcy Clegg came to Vicky with a cushion for her back.

Later the dancing began in another room that extended sideways from the main part of the house. There was a woodblock floor in here, and tall windows in one of the gable ends that looked out across a swimming pool covered over for the winter. Andrew had hired a mobile disco, a boy with two turntables and a set of speakers who had set up some lights that made globs of colour revolve softly in the beamed recess of the roof. The young DJ quickly sized up his audience and opted for an opening medley of pounding sixties rock. The innocent exuberance of lights and music and jigging couples were suddenly so powerfully reminiscent of the student parties of fifteen years ago that Nina found herself laughing to see it. It also made her want to leap up and dance.

Gordon watched the dancers too. He was trying to identify exactly what it was that he wanted, on top of several glasses of champagne and a malt whisky he had swallowed quickly, in the kitchen, with Jimmy Rose. There was Cathy Clegg in some tiny stretchy tube of a skirt that showed off her thighs and small bottom, or Hannah, with her expanse of white breast and her habit of biting her cushiony bottom lip between her little white teeth. Darcy’s women, of course. Not either of those.

He did want a woman, Gordon recognized. In the hot, impatient way he had done when he was much younger. He had to be so careful with Vicky now. Her fugitive sleep, her cramps, her tiredness.

Gordon liked Stella Rose, Jimmy’s wife, who everyone called Star. He enjoyed dancing with her at the Grafton parties, and talking to her too. She had a quick, acerbic intelligence that challenged him and a tight-knit bony body that did the same. To single out Star also made some kind of retort to Jimmy, who was always whispering to and cuddling other men’s wives. But he did not feel drawn to Star tonight. She had been drinking hard, as she sometimes did, and he had last seen her in the kitchen, haranguing kindly Marcelle about something, with dark patches of smudged mascara under her eyes.

There were others, amongst the wider group, but Gordon did not move on to search for any of them. Instead, deliberately, he let his consideration circle back to the new woman in the look-at-me dress. He had met her briefly at the beginning of the evening, what seemed like many hours ago now. She had been polite, but slightly remote. He thought she was aloof, probably considering this party of the Frosts’ to be dully provincial. Then, a while later, she had slipped past in a knot of people and her exotic draperies had fluttered against him.

He noticed that she was standing on her own, apart, and apparently laughing to herself. One of the discs of revolving light, a blue one, passed slowly over her face and then over her hair. It turned a rich purple, like a light in a stained-glass window, and faded as soon as he had seen it. Gordon felt a tightening in his throat.

‘Would you like to dance?’

Nina, that was her name. It came to him, once he had asked her.

‘Thank you.’

She let him take her hand, quite easily and naturally, and lead her into the throng of people. They began to dance. He saw how she let herself be absorbed into the music, as if she was relieved to forget herself for a moment. Some of the stiffness faded out of her face, and left her looking merely pretty instead of taut and imperious.

‘Do the Frosts often give parties like this?’

‘Often. And always exactly like this.’

The flip of his fingers, she saw, acknowledged the combination of sophistication and hearty enthusiasm, champagne and student disco, fancy dress and cocktail frock, that she herself had found so beguiling. Nina had forgotten this man’s name, but she felt an upward beat of pure pleasure to find herself here, dancing, amongst these people who knew nothing about her.

Darcy was lounging in the doorway, observing the dancers, with Jimmy beside him. Jimmy had pulled off the red hood of his devil suit and had then raked his fingers through his hair so that it stood up on top of his head in a crest.

Jimmy murmured to his companion, ‘Who is La Belle Dame Sans Merci? Nobody will introduce me.’

Nina and Gordon were on the far side of the room, absorbed in their dance.

Mick Jagger sang out of the speakers, Pleased to meet you, hope you guessed my name … and all the couples in their thirties obligingly sang back, Whhoo hoo …

‘Perhaps she doesn’t want to meet the Devil,’ Darcy suavely answered. ‘But her name is Nina something, and she has bought the house in Dean’s Row where the Collinses used to live. She is a widow, apparently.’

‘La Belle Veuve, then,’ Jimmy said. And then he added with relish, ‘I smell trouble, oh yes I do.’

Nina had arranged for the car to come back for her at twelve-thirty, and she was ready for it when the time came.

Her dancing partner had been claimed by his rosy, pregnant wife. The little Irish devil man had made a surprising pair with the tall woman with the reflective face. Andrew and Janice had come to the door together, to see Nina off, and had stood shoulder to shoulder, smiling and waving.

In the taxi Nina leaned her head back and closed her eyes.

Two by two, the people swam up in her mind’s eye out of the swirl of the party. She could recall all the faces, not so many of the names. Somebody and somebody, somebody and somebody else. It seemed that everyone was half of a pair. The whole world was populated by handsome, smiling couples, and behind them, behind the secure doors of their houses, were the unseen but equally happy ranks of their children.

Nina’s loneliness descended on her again. It was like a gag, tearing the soft tissues of her mouth, stifling her.

‘Dean’s Row, miss,’ the driver called over his shoulder.

Inside her house, the silence felt thick enough to touch. Nina poured herself a last drink and took it upstairs to the drawing room. She stood at the window, without turning on the lights behind her. The floodlights that illuminated the west front were doused at midnight, but Nina felt the eternal presence of the saints and archangels in their niches more closely than if they had been visible.

She rolled her tumbler against the side of her face, letting the ice cool her cheek.

To her surprise, she realized that the pressure of her solitude had eased a little, as if the statues provided the company she needed. Or perhaps it was the party that had done it.

It was a good evening, and she had met interesting people. They were nothing like her London friends, these Grafton couples, but she was glad that she had met them.

‘And so, good night,’ Nina said dryly to the saints and archangels.