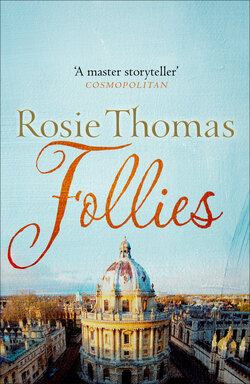

Читать книгу Follies - Rosie Thomas - Страница 7

ONE

ОглавлениеIn a moment, she would see it.

The train swayed around a long curve, and then rattled over the iron arches of a little viaduct. Helen pressed her face against the smeared window, waiting.

Then, suddenly, it was ahead of her. The oblique sun of the autumn afternoon turned the spires and pinnacles to gold, and glowed on the rounded domes. The light made the stone look as soft and warm as honey, exactly as it had done for almost four hundred years.

The brief glimpse lasted only a few seconds, then the train shuddered and clattered into an avenue of grimy buildings and advertisement hoardings. But when Helen closed her eyes she saw it again, a sharp memory that was painful as well as seductive. She loved the place as she had always done, but she was a different person now. She shouldn’t have come back. Home was where she was needed now, not here under these honey-gold spires. Yet her mother had insisted, her face still grey with strain. And Graham, with all the sudden maturity that had been forced upon his thirteen years, had told her that it would break their mother’s heart to see Helen give up now. So she had repacked her cheap suitcase with her few clothes, the paperbacked texts and the bulging folders of notes, and she had come back.

Helen opened her eyes again as if she couldn’t bear to think any more.

The train hissed grudgingly into the station and she stood up as the doors began to slam. Two foreign tourists, encumbered with nothing more than expensive cameras, reached to help her with her luggage. A deafening crackle overhead heralded the station announcement.

‘Oxford. Oxford. This is Oxford.’

The tourists smiled at each other, pleased to have their destination confirmed. They bowed to Helen before they left her.

Where else? she thought. Even the air was unmistakable, moist with the smell of rivers and the low mists that the autumn sun never shone strongly enough to dispel. The yellow and gold leaves in the roadway beyond the station entrance were wet, and furrowed by bicycle wheels.

Helen picked up as much of her baggage as she could manage and went in search of a taxi. It was an unaccustomed luxury and uncertainty sounded in her voice as she told the driver, ‘Follies House, please.’

The oak door was heavy, and studded with iron bolt heads. A drift of crisp, yellow-brown leaves had blown up across the threshold, giving the house an abandoned air.

Helen stopped pulling at the iron ring that hung unyieldingly in place of a doorknob and stepped back to peer at the narrow windows set in the high wall. There was nothing to be seen, not even a curtain in the blackness behind the glass. The traffic, roaring close at hand over Folly Bridge, seemed miles away. It was the gush of running water that filled the air, the river racing between the mossed arches of the old bridge.

Helen glanced down at her luggage, piled haphazardly in the pathway where the taxi driver had left it. Her mouth set in a firm line and she turned back to bang on the door with her clenched fist.

‘Anyone … at … home?’ she shouted over the hammering.

From startlingly close at hand Helen heard footsteps, and then a rattle before the door swung smoothly open.

‘Always someone at home. Usually me,’ the fat woman answered. Helen remembered the facts of the loose grey hair, the billowing, shapeless body and the alert little eyes in the dough-pale face. What she had forgotten was the beautiful smile, irradiating the face until the plainness was obliterated. ‘I’m sorry to disturb you, Miss Pole,’ Helen murmured. ‘The door wouldn’t open. Helen Brown?’ she added, interrogatively, afraid that the woman might have forgotten, after all.

‘You call me Rose, pet. I told you last term, when you came for a room. Don’t forget again, will you? Now then, for the door you need a key.’ The ordinary-looking Yale swung at the end of a strand of dirty orange wool. Rose fitted it into the lock and showed Helen how the door moved easily on the latch. ‘Simple, you see.’ Rose waved towards the stairs. ‘No-one to help with your stuff, I’m afraid. Gerry’s never here when you want him, and I’m far too infirm.’ The smile broadened for an instant, then the fat woman turned and disappeared into the dark as quickly as she had materialised.

Helen scuffled through the leaves and stepped into Follies House.

The hall was dingy and smelt of cooking, but the grandeur was undimmed. It was high, four-square and wood-panelled to the vaulted plasterwork of the Jacobean ceiling. The bare wood stairway mounted, behind its fat balusters, to the galleried landing above. In the light of an autumn afternoon the atmosphere was mysterious, even unwelcoming. Yet Helen felt the house drawing her to it, just as she had done the first time. It had been a brilliant June morning when she had applied to Rose for a room. ‘Not my usual sort,’ Rose had told her bluntly. ‘Mostly I know them, or know of them. Reputation or family, one or the other. But you’ve got a nice little face, and Frances Page won’t be needing her room next term, not after all this bother.’

‘I know,’ Helen had said humbly. ‘Frances is in my College. She told me there might be space here.’

‘Oh well,’ Rose had said, looking at Helen more closely. ‘Why didn’t you tell me you were a friend of Frances?’

And so it had been arranged.

Now, after the long, sad summer, she was here. Usually her family had come with her, driving up to her College in the little car. Helen shook her head painfully. This time she was alone, standing in the muffling quiet of a strange house. Again, through the stillness, she heard the pouring gush of the river as it tumbled past the house and on under the bridge, and the sound soothed her. Determinedly, one by one, she hoisted her cases and boxes over the doorstep and into the hall. With the last one she kicked the door shut on the fading yellow light outside and began to climb towards her room with the first load.

Follies House was square, and the first-floor gallery ran round the staircase which led off up to the third floor. Servants’ quarters, she thought with a faint smile, as she panted up into a smaller corridor, even dustier, with uneven, wide oak floorboards. There was no name-card on the low oak door in front of her, but the room was hers just the same. Helen pushed open the door and dropped her burden gratefully on the worn carpet.

The room was the smallest of Rose’s undergraduate quarters, Helen knew that, but the size was unimportant. What mattered was the view. It was a corner room, no doubt freezing cold in the coming damp of the Oxford winter that already seemed to hover in the air. But there were windows in two of the walls, square windows with stone facings set in the red Jacobean brickwork, with cushioned window seats in the recesses beneath them.

Helen knelt on one of the seats and, through the fog of her breath on the cold glass, stared out over Oxford. Due north, ahead of her, was Carfax with its ancient tower, the crossroads that was the nominal centre of the city. Beyond that lay Cornmarket with its chain stores and shoe shops, and beyond that the dignified spread of North Oxford.

Helen turned away to the second window. There, to the east, was the heart of Oxford. The towers and pinnacles and domes were familiar to her now, but the sight of them spread out before her never failed to thrill her.

A little bit of this is mine, thought Helen, as her eyes travelled from the distant perfection of Magdalen Tower, along the invisible but well-remembered curve of the High past All Souls’ and St Mary’s, to the magnificence of Christ Church’s Tom Tower in the foreground. I do belong here, she whispered to herself, and knew that she was glad to be back. Glad, in spite of and also because of the deadening sorrow that she had left behind in the cramped rooms of her parents’ house.

As Helen knelt on her window seat and watched the teeming life passing to and fro over Folly Bridge, up and down St Aldate’s and past Christ Church, a figure appeared in the ribbed archway beneath Tom Tower, over the main entry. It was a young man in a soft tweed jacket, breeches and tall polished boots. He stood for a moment with his hands in his pockets, watching the shoppers and cyclists and homebound office workers with an air of faint surprise. Then he shrugged, adopting an expression of mild resignation in place of the surprise, and began to stroll towards the bridge. Several of the faces in the crowd streaming past him turned to watch him pass, but the young man was oblivious. He merely lengthened his stride, lifted his head to taste the damp smells of leaves and woodsmoke that mingled with the exhaust fumes, and smiled in absent satisfaction. With the wind blowing the fair hair back from his narrow, tanned face and the brilliance of his smile, he attracted even more attention.

Helen, high up in her window, stayed at the vantage point long enough to register the fact of Oliver Mortimore turning out of Christ Church and down St Aldate’s. He was the kind of Oxford figure whom she had spotted and categorised for herself early on in her life there. She had expected him, and would have been disappointed not to have discovered his kind. She knew that he was ‘a lord, or an earl, or something’ because a breathlessly impressed friend had told her so. And she knew that he drove a fast car, and had beautiful friends and expensive tastes, because she had observed as much for herself. Oliver Mortimore was a famous figure in Oxford, well known even to Helen, even though he moved through its world at a level that couldn’t have been further from her quiet round of library, lecture room, and College.

Helen smiled tranquilly and sat for a moment more, immersed in her own thoughts as she stared unseeingly out at the view. Then, reminding herself that there were things to be done, she swung her legs briskly off the window seat and set off for the next armful of possessions.

Her foot was on the last step of the broad lower staircase when the front door banged open. It brought with it a gust of damp, river-redolent air, a small eddy of dead leaves, and Oliver Mortimore. In the dimness he stumbled against Helen’s shabby pile of belongings, lost his balance and fell awkwardly. Oliver swore softly. ‘Jesus, what is all this? Looks like a fucking jumble sale.’

Helen sprang forward, contrite. ‘I’m sorry. It’s all my luggage. Stupid place to leave it.’

Oliver looked up at her, and the frown disappeared from between his eyes.

‘I didn’t see you there,’ he said. ‘Sorry for the language. Good job I didn’t break my leg on your impedimenta, that’s all. It’s the first Meet tomorrow.’

Helen nodded politely, evidently not understanding, and Oliver grinned at her as he scrambled up. She saw that there was a long scrape in the high polish of his boots, and had to resist the impulse to kneel down and rub the blemish off such a vision of perfection. At close quarters Oliver Mortimore was not only the most beautiful but also the most physical man she had ever encountered. He radiated such confidence, such highly-charged animal pleasure in his own existence, that set her skin tingling in response. He made Helen feel hot, and shapeless inside her clothes. Oliver held out his hand. He was six inches taller than Helen, but it felt like twice that.

‘I’m Oliver Mortimore,’ he said lightly. ‘Who are you, and why don’t I know you?’

‘I know who you are,’ Helen countered. ‘You don’t know me because there’s no particular reason why you should. My name’s Helen Brown.’

‘And what are you doing at Follies, Miss Brown?’

Helen moved forward under his gaze to pick up one of the scattered boxes.

‘What I’m doing is moving in. I’m going to live here for a year.’

Oliver was staring at her now with undisguised interest.

‘Oh really? You’re not in the usual run of socialites and harpies that Rose collects around her, are you?’

He was so clearly stating no more than the obvious that Helen found herself laughing with him.

‘I imagine not. Frances Page let me inherit her room. We’re friends,’ Helen told him crisply, ‘in a way.’

Oliver raised his eyebrows, but politely made no other comment on such an unlikely sounding friendship. ‘Ah, unlucky Fran,’ he said. ‘Perfectly okay for one’s own use, of course; but not very clever to start dealing in the stuff. Still, if you’re a girl with expensive tastes and no cash, like Fran, the books do have to be balanced somehow.’

Helen looked away. She didn’t care to hear muddled, aristocratic, silly Frances spoken of so lightly. For the time that they had lived in adjacent College rooms, she had been a good friend to Helen. She hadn’t been sent to prison for what Helen thought of as her witless dabbling on the fringe of the cocaine-peddlers’ world, though she could have been. But she had been sent down from Oxford, and Helen missed her.

Oliver was counting up the remaining items of Helen’s luggage.

‘Cases, three; cardboard boxes, miscellaneous, secured with string, four. You can’t possibly manage all this yourself. Where’s bloody Gerry?’

He picked up the nearest box. ‘Oof, what’s in here? Rocks or something?’

Helen put out her hand. The material of his sleeve felt very soft. ‘Books, mostly. Don’t bother, really. Rose told me I’d have to cope myself, and I’m quite ready to.’

‘Lazy old trout.’ Oliver had already started for the stairs. ‘Where’s your room?’

‘Top floor.’ Helen had no alternative but to pick up the remaining case and follow him.

Oliver chuckled. ‘Good old Rose. Trust her to have stuck you right up there. Who’re the lucky occupiers of the smarter quarters this year?’

‘No idea. Isn’t this Gerry one of them?’

‘God, no. Gerry is Rose’s half-brother. He calls himself a writer, but he’s actually a drunk and a lecher. He also claims to be a distant relative of mine, because Rose is, but I find that hard to swallow. You’ll be seeing lots of him, which is hard luck.’

They reached the door of Helen’s room and Oliver shouldered it open. He dropped his armload and strolled over to the window. ‘Nice view, anyway. Hey, you can almost see my windows over at the House.’ Oliver flexed his shoulders inside their second skin of tweed, easing them after the long pull up the stairs, then turned back to Helen.

‘Come and have tea with me, won’t you? Tomorrow. No – wait – Friday. Yes?’

Helen looked straight back into his tanned, smiling face for a long moment before she answered. But there was no possibility that she could refuse.

‘Yes. On Friday, then.’

To her amazement, Oliver leaned forward and kissed her, quite casually, on the corner of her mouth. ‘Cheer up,’ he said softly. ‘You should smile a bit oftener. You’ve no idea how much it suits you.’

From the doorway he waved, without looking at her again, and Helen heard him clatter away down the stairs.

For a moment she stood stock-still in the middle of the room, absently touching the corner of her mouth with her fingertips. Then she sank down at one end of the narrow bed. Follies had cachet, Helen knew that. The idea of Helen Brown, who had none at all, living there had given her some rare moments of private amusement over the summer. And now here she was, in the house for barely an hour and already she had been invited to tea and kissed by Oliver, practically a being from another planet. Helen rocked back on the bed and laughed out loud, a transforming giggle that Oliver would have approved of. It was absurd to think anything of their encounter, let alone to take it as an augury for the new year, but she would do it anyway. It was a good one, Helen was sure of that.

Chloe Campbell registered the road sign as it flicked past her on the motorway. Oxford 15 miles. Shit, almost there. A little shiver of nervousness snaked along her spine before she realised it. Well, there was nothing to be apprehensive about. Nothing at all. Chloe jammed her foot down on the accelerator and swung her slick, little black Renault Gordini out into the overtaking lane. A glance in the mirror showed the family saloons dropping satisfactorily away behind her, and she relaxed her too-tight grip on the wheel. Nice little car, she thought. Thank you, Colin. Thank you, but goodbye in the end, just the same. Goodbye to a lot of things, come to think of it.

Chloe, darling, are you serious about all this?

The question was addressed to her own reflection briefly glimpsed in the mirror. The huge green eyes with their sooty black lashes were perfectly made up as usual. The dark coppery-red hair gleamed over the diamond ear-studs, just as always. But where were all the other things she used to identify herself by?

Chloe began her reckoning once more, already repeated once too often since she had left London.

No job, to start with. She had resigned from that, her ridiculously well-paid job as a top copywriter in a smart little ad agency. Well, except for the money, that was no great loss. Trying to create the perfect lines for the perfect housewife in her dream kitchen with the superlative packet soup bored Chloe nowadays, like so many other things.

No lover, either. All the available ones bored her too, and it irked her to think of the unavailable one. Leo Dawnay, damn him. All of this was really because of him. Leo was in the business, the perfect Englishman who had made it his particular business to trade on that on Madison Avenue. A big joint campaign had brought him briefly back to London, and into Chloe’s bed. It was Leo who had said it as they lay wound together after one of their long evenings of love-making.

‘You don’t have to be so competitive in everything. You’ve got an intellectual chip on your shoulder, that’s your problem.’

‘What? That’s crap.’ Chloe sat up and the sheets fell away from her silky shoulders. ‘I’ve got twice the wits of any of the little graduate mice that they send along to type my letters and answer my phone nowadays. When I was eighteen I just wanted to get on with life, not moulder in some dusty library.’

‘Well,’ Leo had said coolly, ‘you mentioned graduates, not me. But you’re twenty-eight now, and perhaps you’ve done enough getting on. Take some time off. Test yourself a bit. You’d enjoy it.’

Leo, of course, had been at Balliol. And had taken a First.

‘I don’t need it,’ Chloe had whispered into his thick, black hair. ‘What I need is you. Again.’ And his hands had moved across her belly and between her legs once more with unquestioning assurance. In the first pleasure of the moment Chloe had forgotten his words, but later they kept coming back to her. She thought about them when she recognised the uncomfortable feeling that permeated her life as boredom, and she remembered them again when she realised one day that she wasn’t interested in the challenge of pitching for a major new account. She felt that she was running along in comfortable, well-oiled grooves, and that she wasn’t thinking about anything, any more. She began to be afraid that even falling in love with Leo had been no more than a way of filling the vacuum that yawned in the centre of her life.

Another day she had pushed aside the story boards for a new bra commercial and typed a letter to the Principal of an Oxford College, making the choice just because she had seen the College featured in a magazine.

‘That’s that,’ she thought. ‘The answer will be no, of course.’

But with surprising speed, the letter had led to an interview with the austere Principal in her book-lined drawing room. Then, after some hasty reading, there had been papers to write on Victorian novelists and Romantic poets. She had been interviewed again, making her joke to her friends that she felt that she was being looked over for the chairmanship of Saatchi and Saatchi, not a commoner’s place at an obscure women’s College. At last the Principal had told her: ‘We have a policy here, Miss Campbell, of accepting mature students and other unusual folk. You’re more mature than most, of course, and you’ll have a lot of catching up to do. But we think you’ll make a useful contribution of College life, even if you turn out not to have a first-class mind. Would you like to come up this October?’

At first, going to Oxford had been no more than a teasing idea for Chloe. She had wanted to prove to Leo that she could win a place, and she had wanted to show him that it impressed her so little that she could turn it down without a second thought. Then she had found herself enjoying the preparation for the entrance papers, hurrying home to dig poetry books out of the inner pocket of her briefcase instead of going out to cocktails and dinners with friends from the agency. She had started to use the cool, remote thought of Oxford as an antidote for her grating London world.

Yet, even so, when the moment finally came she was shocked to hear herself saying, ‘Thank you, Dr Hale. I’ll do my very best. And I’d like to start in October.’

Now, Leo was back in Manhattan, or with his top-drawer wife up in East Hampton or wherever it was. Chloe Campbell was slowing down before the Oxford bypass, her car loaded with her expensive but not-too-new-looking leather suitcases, piles of crisp empty notebooks and brand new standard texts, and feeling as apprehensive as any sensitive adolescent on the way to a new school. It was too late now. Chloe negotiated the tangled city traffic, and parked the Renault defiantly half on and half off the pavement on Folly Bridge. Only a single window in the old house showed a light.

Chloe hitched her shaggy wolf-pelt jacket closer around her and began to pick her way down the slippery stone steps. Her hair looked as bright as a beacon in the wintry dusk. Before she reached the front door which had barred Helen’s entry, it swung open and Gerry Pole lounged out. His grey sweater was filthy and his lined face was unshaven, but the tattered remnants of a more wholesome romantic youth clung about him. Chloe responded with a brief flicker of interest as Gerry grinned at her.

‘One of Rose’s new tenants, I take it? And very lovely, too. I’m Gerry Pole, by the way, token male on the premises …’

‘Oh, good,’ Chloe said quickly, waving up towards her car perched on the bridge. ‘Perhaps, then, you could possibly give me a hand with my things? So inaccessible, down here.’

‘Delighted.’ Gerry smiled again, showing off the attractive crinkles around his pale blue eyes and revealing uncared-for teeth.

So Chloe made her entrance into Follies House burdened with nothing more than her handbag and her portable typewriter. Gerry obligingly toiled to and fro with the leather cases and set them carefully down in Chloe’s first-floor room. The long windows looked out on almost total blackness now, but the little lamps inside glowed invitingly on panelled walls and solid furniture. Chloe looked around her with approval. The panelling was painted soft bluey-green, like a bird’s egg, and the curtains and faded Persian rugs stood out against it in warm reds and garnets. She laid her typewriter down on the bare desk and switched on the green-shaded library lamp to make a little, welcoming circle of light.

Here, Chloe thought with a sigh of satisfaction, she could work. Books. Peace, calm and no hassles. Perhaps this crazy idea was going to work out after all. A little sound from behind her reminded her that Gerry was still hovering by the door. She shot him a brilliant, dismissive smile.

‘Thanks very much. I expect we’ll be meeting again soon, if you live here too?’

‘Oh yes, certain to,’ Gerry rubbed his dry hands expectantly. ‘I could more than do with a drink now, in fact, after all that lifting. Won’t you join me? I’ve got a little something …’

The flip-flop shuffle of down-at-heel slippers came up the stairs and along the gallery towards them. A second later the mass of Rose’s bulk filled the doorway. She jerked her head at her half-brother and, with surprising speed, he was on his way.

‘Another time, then,’ he winked at Chloe and vanished.

Rose eased herself down on the foot of the bed and rested her podgy hands on her spread knees. The two women smiled.

‘Still not quite sure about it, eh?’ Rose asked. Chloe took off her jacket and stood stroking the fur absently.

‘Not a hundred per cent,’ she admitted. ‘Or even fifty. Sometimes it feels like a crazy decision to have made, three years up here reading George Eliot and trying to make ends meet on a grant. Not that it isn’t perfect to be at Follies House,’ she added warmly.

Rose chuckled flatly and her little eyes flickered over the diamonds in Chloe’s ears, the discreet but heavy gold chain around her neck and the supple, rust suede of her tunic dress. ‘Don’t tell me that girls like you ever have to manage on a grant,’ she murmured. ‘And you’ll enjoy it here, mark my words. All kinds of people to meet, for a start. Different from your London ad men.’

‘I hope so,’ countered Chloe fervently.

‘Look at me,’ Rose went on. ‘I just have this house, nothing else. But enough goes on here to keep me looking forward to tomorrow.’ As she winked at Chloe she looked, for an instant, very like her half-brother. ‘So long as I choose the right people to live with me here at Follies, I have everything I need in these four walls. Which is just as well, because where could I go outside with a face and figure like mine?’ The white hands fluttered vaguely over the forbidding fleshy mass. Chloe could do no more than turn the talk with a question.

‘Who else lives here now? Since Colin Page’s sister left?’

Rose’s face brightened in anticipation. ‘Ah. All new this term. You, dear, of course. A little mite called Helen, who you shall meet in one second, unless my predatory young cousin has swept her out of the house already. And by the end of the week there’ll be a pretty love called Pansy. Such a beautiful name, isn’t it? There’s just the three of you. I think you’ll make such an interesting combination.’ Rose’s fingers knitted across the mound of her stomach as she nodded happily at Chloe. Just for the moment she looked like a complacent puppet-mistress with her pretty dolls on sticks, waiting for the show to start. The idea amused Chloe rather than alarmed her. Why shouldn’t Rose live a little through her lodgers, after all?

The landlady heaved herself to her feet and padded to the door.

‘Helen!’ she shouted up into the darkness. ‘Helen, darling, come down and meet a new friend.’

Chloe wasn’t sure who she had been expecting as another member of Rose’s ‘family’, but the figure who appeared obediently a moment later came as a surprise.

‘Helen Brown, Chloe Campbell,’ Rose said easily. ‘And now I’m off. Tell me if you need anything simple. Anything strenuous, ask Gerry.’

‘Hello,’ Chloe said to the girl in the doorway. Helen was small and fine-boned, too thin, with collarbones that showed at the stretched neckline of her royal blue sweater. In her grey corduroy skirt she might have been a fifteen-year-old schoolgirl, but something in the poised tilt of her head told Chloe that she was older, twenty or perhaps even a little more. Her skin was very pale and creamy under a mass of short black curls, and the huge grey eyes in the heart-shaped face were smudged underneath with violet shadows.

‘Hello,’ Helen responded warily. There was an exotic atmosphere in the room that wasn’t just compounded of expensive scent and suede, nor of the rich colours and fine proportions that were missing from her own room upstairs. The atmosphere came from the girl herself, prowling like a taut red-brown tiger on the Persian rug. Yet as soon as Chloe smiled at her it was different again. She looked ordinary, friendly and inquisitive now. Chloe seized Helen by the wrist and propelled her to an armchair.

‘For God’s sake, sit here and talk to me while I get my bearings. It’s my first day at Oxford, and you’re the first real person I’ve met. Are you new, too?’

Helen shook her curls vigorously. ‘No. My last year. But it’s my first time living out of College. Follies isn’t exactly my natural habitat either. It’s been a strange day.’

Chloe was rummaging in one of her bags. At length she lifted out a green and gold bottle and brandished it triumphantly. ‘Share this with me? It won’t be very cold, but it’ll do.’

Helen watched the champagne sparkle into a pair of glasses and then lifted hers to Chloe. The strangeness of the day evidently wasn’t over yet, and something inside her didn’t want it to be.

‘Welcome to Oxford,’ she toasted the newcomer.

‘And to Follies House.’ Chloe’s bright green eyes glittered at her over the glass and they drank together.

They finished the bottle as Chloe unpacked. Helen sat curled up in the armchair with her cold feet underneath her and listened as the other girl talked. The champagne sent unfamiliar waves of warmth and lassitude through her veins, and she found herself sinking into the cushions and smiling at the warm colours and scents around her. Chloe’s cases seemed to contain unbelievable piles of silks and cashmere and butter-soft leather, marching ranks of shoes and boots, and handbags in soft, protective wrappings.

There were other pretty, more eccentric things too. A huge, fragile butterfly gaudily painted on rice paper swung airily on one wall. A silver-framed mirror bore the raised motto ‘Look, but linger not’. Chloe made a mock-grimace into it as she swung it into place on the mantelpiece. A collection of heart-shaped tortoiseshell frames all seemed to enclose pictures of different men. All these Chloe laid out among the vanity cases, silver hairbrushes and tiny crystal bottles.

All the time, as she moved to and fro, Chloe went on talking. Had Helen but known it, she needed to talk more than anything else. She needed to put London firmly behind her; Leo and the agency and San Lorenzo and everything else. Almost by accident, the possibility of Oxford had today become a reality. Chloe was so used to feeling confident that it was doubly disconcerting to be nervous and apprehensive. Talking to this quiet girl seemed to help. She told Helen everything, but it was as much for Chloe’s own benefit. The explanation helped to put this mad, life-changing decision into perspective. She had no need of an Oxford degree and it was exactly the abstract, stringent challenge set by gaining one that Chloe knew she needed.

With the last drop of champagne she smoothed a remaining square of tissue paper and tucked it into the last empty suitcase. Helen, who had drunk the lion’s share of the champagne as she listened, smiled vaguely up at her.

‘So here I am.’ Chloe gestured theatrically. ‘Unfettered, and as yet unlettered …’ they giggled happily, ‘… although Dr Hale is about to put that right. And feeling much, much better.’

She stopped in front of Helen and put her hand over the younger girl’s. ‘Thank you for listening to all that. You’re a good listener, aren’t you?’ On impulse she knelt down and took both of Helen’s thin hands between her own warm ones.

‘Helen, I’ve done all the talking, like a self-centred old witch. Now you tell me some things. You’re sad, aren’t you? Why’s that?’

Helen looked into Chloe’s concerned eyes and in an instant the champagne, her loneliness and this unexpected warmth from a woman she barely knew blurred inside her. Boiling tears swept down her face. In an instant Chloe’s arms came round her and Helen’s face was buried in soft suede and the thick mass of dark red hair.

‘What? Helen, what is it?’

There was a second’s quiet before she answered. ‘My father. My father killed himself.’

At once Chloe’s arm tightened around the younger girl’s thin shoulders, but she said nothing.

‘Yes,’ said Helen after a moment, speaking as softly as if to herself. ‘It was in the summer. The middle of August, when the world was hottest and brightest outside. Daddy must have found that very hard, looking inwards at the darkness gathering for him in our house. I suppose it had been dark for weeks before that, months even. At the end, it was as if everything positive and hopeful had wilted, through lack of light. Even our love for him seemed to have no life in it any more, because he couldn’t lean on it. Right at the end, in the last hopeless days, I was still sure that it would brighten the gloom for him. But it didn’t, because he killed himself.’

‘Why did he do it?’ Chloe whispered, as gently as she could, and felt an answering movement that might have been a shrug.

‘It’s a banal story, I suppose,’ Helen told her with a new bitterness in her voice. ‘He lost his job. Not a particularly high-powered job, or anything, just as a middle manager in a middle-sized manufacturing company. My father was always a quiet man – grey, they call it here – quietly doing what he was supposed to do. He came home in the evenings on the train, mowed the lawn, listened to the radio, did what was involved in being a husband and father, but mostly he just did his unassuming job. He must have enjoyed it … no, perhaps needed it is nearer the truth. Because when they took it away, he collapsed inside. They did it all particularly brutally, just pushed him out with a tiny amount of compensation. But that’s not unusual. In my father’s case, I think he knew from the first moment that there was no chance of finding another job. And he wasn’t the kind of man who could turn round and just create another life for himself. He was too mild, and puzzled, and overwhelmed by the circumstances of the life he already had. He just let himself feel shamed and rejected. There was no money, you see. He had no prospects at all, and there was nothing he could do for us or anyone else. So he retreated further into the dark and silence, leaving us behind. Until the day came when he went into the garage, locked the doors and turned the car engine on. He lay down on a tartan knee rug that we used to keep on the back seat. Do you know, he was still wearing a tie?’

‘What about your mother?’ Chloe asked.

‘She loved him. It was the worst kind of shock for her. She’s not very good at being alone.’ Helen rubbed her face with the flat of her hand and, as if noticing that Chloe’s arms were still around her, stiffened and drew back a little. Chloe let her go, noticing the tired pallor and the shadows under her eyes.

‘And you?’ she asked. Helen shrugged again.

‘There are money problems, of course. My mother does some part-time supply teaching, and there’s a tiny pension. But my brother is still a child, really, and needs everything. And there’s a big mortgage, the three of us to clothe and feed, all the household bills. So much money to find, and nowhere …’ Helen’s voice trailed away hopelessly. When she spoke again the reawakening of anxiety had drained away all the colour that the champagne had put into her cheeks. ‘I shouldn’t be here. I should never have come back. The right thing would have been to get a job, doing anything, anywhere. Whatever brings in the most money. I can help a tiny bit out of my grant, but …’ The shrug, when it came, was defeated, ‘… it isn’t enough.’

‘But they insisted, your mother and brother, that you did come back? Said you’d be letting them down, and your father, if you didn’t?’

Helen smiled wryly. ‘Exactly. How did you know that?’

Chloe laughed at her. ‘Because it’s what any right-thinking people would have said. It matters, doesn’t it? You’re probably very bright.’

Helen was too natural to attempt a modest contradiction.

‘I’m bright enough. I could get a First, if I’m lucky. Before Dad died I’d wanted to stay on and do research. Now, of course, I’ll have to look for something that’s more of a paying proposition. But not to have got a degree at all, that would have been very hard.’

As she watched the anxiety in Helen’s face, Chloe felt the weight of her own privilege. Her own background was not wealthy, but never at any time since her early and rapid success at her job had she had to deny herself anything. Travel, new books, designer clothes, a luxurious flat were as much an unquestioned part of her life as they were remote from Helen’s. Chloe reflected that even her place at Oxford had begun as a move in her sexual game with Leo. Set beside Helen’s difficulties and her family’s sacrifices, that suddenly seemed frivolous and wasteful. She shook herself in irritation and turned to listen to Helen again. The other girl’s face was brighter and more animated now.

‘It’s strange to be back here, after so much. And in this weird house …’

‘Isn’t it?’ Chloe grinned at her.

‘… I’d only been in the house an hour before Oliver Mortimore appeared, kissed me, and asked me to tea on Friday.’

‘Who’s that?’

Helen’s smile transformed her face and the grey eyes shone with amusement in the absence of the shadows. She had no idea why she was talking like this to Chloe, but it felt perfectly natural.

‘Oh, a bright star in the local firmament. Rich, titled, amusing, and the most beautiful young man you ever saw.’

‘Love the sound of it,’ said Chloe, ‘but does such a sum of perfection do anything as ordinary as have tea?’

The sound of their laughter reached Rose as she slid across the dark hallway below, and it brought a flicker of a satisfied smiled to her broad face.

‘Now I’m sitting here drinking champagne and talking to you as if I’ve always known you,’ Helen went on. ‘Odd, isn’t it? It feels a long way from home, too, and that isn’t fair.’ The sadness flooded back into her face.

‘Listen to me, Helen,’ Chloe said firmly. ‘It would be wrong to destroy the value of being back here by immersing yourself in guilt and grief. That would make your family’s sacrifice useless, wouldn’t it? You can’t forget your father’s death – how could you? – and you shouldn’t try. But you can find your own strength to carry on positively, where he couldn’t.’ Chloe broke off and bit her lip. Her face reddened as she met Helen’s serious straight gaze. ‘I don’t know why I’m preaching at you,’ Chloe said uncomfortably, ‘particularly when I’ve got the feeling that there are several things for me to learn myself before too long.’

The silence stretched on for a second or two before Helen broke it. ‘You’re right, though. Thank you, Chloe. Tea on Friday with Oliver,’ she added lightly. ‘I’ll have to be profoundly positive to cope with that. Will you … do you think you could lend me something beautiful to wear?’

There was relief in Chloe’s face as she responded warmly, ‘With pleasure. To seal the deal, let’s go out and eat now – I’m ravenous. You tell me where’s good, and I’ll treat you. Okay?’

‘Sounds wonderful.’

The two girls left Follies House together and climbed the cold, slippery steps up to the bridge. Inside her Renault, Chloe revved the engine decisively and glanced at Helen’s profile beside her. ‘Well then, Oxford, here we come,’ she murmured into the icy air.

On Friday afternoon Helen slipped through the great wooden gates of Christ Church and crossed to the porter’s glassed-in box, incongruously snug under the splendour of Wren’s tower.

‘Oliver Mortimore’s rooms, please?’ she asked, remembering that Oliver had made no mention of where he was to be found. Perhaps he just assumed that everybody knew.

‘Canterbury Quad, Miss,’ said the porter, pointing, and gave her a staircase and room number. Following his directions Helen came out into the sunlight in Tom Quad. For a moment, nervous but unwilling to admit to herself that a mere tea-party could intimidate her, she stood to admire the view. Cardinal Wolsey’s great unfinished quadrangle seemed to capture and intensify the Oxford light. The gold of late autumn afternoon sunshine was reflected from the deeper gold stone, the rows of leaded windows, and the flat face of the water in the fountain basin. The space seemed immense and airy, yet the proportions made it intimate, too. The only sounds, magnified in the stillness, were the faint splash of water spouting from the statue of Mercury, and the whirr of cameras belonging to a distant group of Japanese tourists. Ahead of her the smooth green lawns rolled away to encircle the fountain and its fringe of lily pads. An undergraduate in a fluttering black scholar’s gown brushed past Helen and it occurred to her that, tourists apart, this scene must be almost unchanged since the sixteenth century.

Then in a babble of noise a crowd of jostling people emerged from one of the doorways and simultaneously a blare of music burst from an upstairs window. Helen jerked herself back into the present and walked on towards whatever awaited her in Oliver’s rooms.

She found Canterbury Quad without difficulty. Built more than two hundred years after Tom Quad, it still looked to Helen profoundly ancient and magnificent as she stared up at its classical proportions. She was used to her own College, of which the oldest parts were late nineteenth century, and to its comfortable air of being a random collection of reasonably well-preserved outbuildings to something much more important.

Oliver’s rooms were on the first floor of the central building. Helen read the white-painted names on the board in his staircase doorway: Mr G.R.S. Sykes, Lord Oliver Mortimore, Mr. A.H. Pennington. At the top of the stone staircase she came to Oliver’s outer door, open, and then tapped lightly on the inner one.

‘Cm’in,’ someone shouted. Helen squared her shoulders inside the vivid scarlet of Chloe’s brief sweater dress, glanced down briefly at what felt like far too much leg which it left on show, and went inside.

The room seemed at first sight to be uncomfortably full of people, all of them women. The atmosphere was charged with smoke and the sound of laughter and clamouring, insistent talk.

‘… all through the Vac, darling. Not just in London, but in Italy as well …’

‘… so I told him to stuff it. No, honestly, he was such a swine …’

‘… Mummy bought it in the end, it was so funny …’

Everyone seemed to know everyone else very well indeed. Helen’s first impulse was to turn and run, but then she saw Oliver refilling someone’s glass. There was no sign anywhere, Helen realised, of a teacup or a piece of buttered toast. The carpet was cluttered with glasses and ashtrays.

‘Hello,’ Oliver said beside her, surprising her again by his height. His kiss, quickly brushing her mouth, surprised her less this time but had no less of an effect. Oliver took her hand and helped her to pick her way through the sprawled legs and gossiping bodies. ‘You look very pretty,’ he told her casually. ‘Red suits you almost as much as smiling.’ A blonde girl with a sulky face jerked her head up to look at Helen as she passed. There was a sofa in the corner, occupied by yet another pair of girls. Oliver eased her down between them, and they made room for her reluctantly.

‘You must know Fiona? No? And Flora? Well then, now’s your chance. This is Helen, and this … is … Helen’s drink.’ Oliver handed her a glass, winked, and went away.

Two surprised faces stared at Helen. Politely, but insistently, with their questions, they tried to find out who Helen was and where she fitted in. It gave Helen a kind of half-satisfaction to demonstrate that she didn’t fit in anywhere, but once that was done the girls went back to their conversation, leaning across her in their animated talk. Helen wriggled back against the cushions to look at the rest of the room.

It wasn’t all girls, she saw now. Three or four young men, in jeans and sweaters like Oliver, lounged among the more carefully turned-out girls. The striking exception was a dark, confident-looking man with a high-bridged nose and long hands that he used to make incisive gestures as he talked. He seemed older than the others and was dressed differently in a loose, pale jacket and beautifully-cut trousers with front pleats. He evidently felt Helen’s stare from across the room because he stopped talking, and his eyes held hers for a second. Then he raised his eyebrows in surprising, friendly complicity. Helen guessed at once that he didn’t belong here either, but he was making himself ten times more at home than Helen herself. After a moment he came over to her and helped her up from her captivity between Flora and Fiona.

‘More room on the window seat,’ he grinned at her. ‘I’m Tom Hart.’

Expertly he ensconced them on the cushioned seat where they were half hidden from the rest of the room by loops of curtains.

‘Well?’ he went on, lighting himself a cigarette. Helen shook her head at the held-out pack. He sounded American, she thought. What was he doing here?

‘Helen Brown,’ she told him, and to forestall a repeat of her interview with Fiona and Flora she added, ‘I don’t know Oliver from London, or from Gloucestershire either. I’m not a friend of Annabel, whoever she is, nor of any of these people.’ Helen’s small, firm chin jerked towards the chattering roomful and Tom grinned at her again. ‘I met Oliver once, at Follies House, which is where I live, and he asked me to tea. God knows why, now I come to be here.’

She lifted her glass to Tom and took a gulp of the cold white wine.

‘Quite,’ said Tom equably. ‘But I think that one might as well make the best of Oliver’s excellent Alsace, now that one is here. Noll!’ he shouted, and Oliver drifted over to refill their glasses.

‘Take good care of her,’ he told Tom smoothly when he saw Helen behind her half of curtain. ‘I shall be needing her as soon as all the rabble has gone.’

Tom ignored him. ‘Follies?’ he asked her. ‘Where Frances was going to live?’

Helen nodded, and Tom’s face set harder for a moment. ‘I miss her,’ he said. ‘She’s very unlucky, and very helpless.’

Helen knew from that moment that she and Tom would be friends.

‘Mmmmm.’ Tom was looking harder at Helen now. ‘D’you act at all?’ He turned her face to the light and stared a little too deeply into the grey eyes.

‘Act?’ Helen blinked and caught herself blushing. ‘No, not at all. I couldn’t. Far too inhibited.’

‘Pity. I’m directing the OUDS major next term. As You Like It, you know. I thought you might like to audition for me.’

‘No, thanks.’ Helen shuddered at the idea. ‘But I’ll come along and see it. Will that do?’

Her turn had come, she thought, to ask questions. ‘You’re American, aren’t you? Are you studying here?’

Tom Hart laughed at the idea. ‘Hell, no. Well, not in the conventional way. I’m a theatre director, and I’m spending a year or so at the Playhouse here. Purely in an assistant capacity, you understand, as they keep reminding me. My old man’s in the theatre in New York. Management.’ Something flickered in Tom’s face, as if a disagreeable memory had bothered him for a moment, before he went on. ‘I needed some time away from home, before deciding what to do for real, so here I am. One of my projects now is this students’ Shakespeare. As a matter of fact, in a brilliant piece of innovative casting, Oliver is to be my Orlando.’ Tom confidently waved away Helen’s start of surprise. ‘You’d be amazed. He moves beautifully, and he has a real unaffected feel for the verse. You may think he’s a mere aristocratic thicko, with a flair for nothing more taxing than horses and dogs, but you’d be wrong.’

Helen’s gaze travelled from Oliver, tall and tousled in the middle of his friends, and back to Tom. There was something in the way that the American looked at Oliver, with both fascination and a kind of unwilling admiration, that puzzled her.

‘Anyway,’ Tom went on quickly, aware that Helen was watching him, ‘Orlando himself isn’t a character endowed with a great deal of brain. No, Rosalind’s the important one, and I can’t find the right girl anywhere. I was hoping I might spot someone here amongst Noll’s grand friends, but they’re all far too old already. Look at them.’ He waved his hand expressively across the room. ‘Twenty years old and experienced enough for forty. I need someone fresh, and full of innocence, yet with that sexy edge of natural cleverness and the beginnings of maturity. A bit like you. But not really like you,’ he added, with beguiling frankness.

‘Thank goodness.’ Helen smiled back at him.

Oliver was seeing people to the door. There was a flurry of kissing and hand-waving, then when Oliver turned back into the room Helen saw the sulky blonde girl jump up and push her arm through his. There was a possessive glow in her face and Helen thought, at once, Of course he would have someone. The little, frivolous flame of excitement that she had been shielding went out immediately. The blonde girl tugged Oliver’s head down to hers and kissed his ear, then let him go with a tiny push.

Tom stood up and pushed his hands deep into this pockets. ‘Time I was off,’ he told Helen. ‘Sure you won’t audition for me?’

Helen shook her head. ‘No. I’d be no good. I’m too busy, anyway. I have to work.’

Tom stared at her for a moment. ‘Jesus, you can’t work all the time. That’d be very dull.’

Helen was aware of a prickle of annoyance. She felt that this dark, forceful man was pushing her in some way and she recoiled from the idea.

‘I am dull,’ she told him dismissively.

Tom’s face remained serious but there was an underlying humorousness in it that threatened to break out at any minute. ‘Somehow I doubt that,’ he said, very softly. ‘But it was only an idea. See you around.’ With a casual wave that took in Oliver as well as Helen, he was gone.

Helen realised that she was almost the last remaining guest. The blonde girl was at Oliver’s side again, turning her pretty, petulant face up to his. ‘Oliver,’ she said in a high, clear voice, ‘so lovely to see everyone again. But,’ and there was no attempt to lower the upper-class tones, ‘the mousy girl in red, who on earth was she?’

Oliver’s good-humoured expression didn’t change, but he shook his hand free. ‘Don’t be such a cow, Vick. I don’t know any mice. Where’s your coat?’

‘Don’t bother, darling,’ Vick said sweetly. She blew him a kiss, danced to the door and slammed it behind her.

At last, Helen saw that she was alone with Oliver. He came, picking his way through the debris of bottles and glasses on the floor, and held out his hands to her.

‘You’ve such a sad face,’ he said. ‘Didn’t you like my party?’ His hands, as they closed over hers, felt enormous and very warm.

‘I liked Tom Hart,’ Helen told him carefully. ‘I’m sorry about looking sad. It must be the way I am.’ There was no question of confiding anything to Oliver. Helen was still surprised that she had let out so much to Chloe. Yet Helen was shrewd enough to know that the very remoteness of Oliver’s world from her own was part of the unexpected, exotic fascination that she felt for him. She was clever enough too to guess that whatever it was that Oliver saw in her, he wouldn’t be attracted by the poverty and awkwardness of her background.

She felt, for an instant, guilty of disloyalty, but she turned the thought away deliberately. What was it that Chloe had said? ‘Find your own strength to carry on. Positively.’ Well, she would do just that.

‘I shall have to try and cheer you up,’ Oliver was saying lightly. ‘Here. Have another drink. Always helps.’ He filled her glass up with the heady, flowery wine and came to sit beside her on the window seat. His long legs sprawled in the faded blue jeans, and his forehead rested against the window pane as he stared out. After a moment’s silence, in which Helen’s eyes travelled from the clear-cut planes of his face to the tiny pulse that jumped at the corner of his eye, Oliver said, ‘So quiet. Just the light and the dark out there. No talk. No noise or confusion. Do you ever wish that you could keep moments? Freeze them or something, just the odd minutes when everything is right. There are so bloody few of them.’

Even in your life? Helen wanted to ask. Perhaps after all he wasn’t such a bizarre choice for Orlando. He had the face of a romantic hero, and there was enough of uncertainty in it now for her to imagine him as a boy in love with an illusion.

‘Times when I want to stop everything, and say yes. Like this. This is how I want it to be?’ Helen answered him. ‘Not very many. Some, perhaps.’ Like now, she could have added. Being here with you, of all strange people, talking like this.

Oliver stopped staring out into Canterbury Quad as if after all he was rejecting this moment as one to be kept.

‘Well, what shall we do? More drink?’ He waved the bottle and when Helen shook her head he refilled his own glass and drained it. ‘Mmm,’ he murmured, and lifted Helen’s hand from where it lay in her lap. He traced the shape of her fingers and the outline of her nails with his own forefinger and then, with his face turned away from her into the room, said, ‘Would you like to go to bed?’

The words seemed to hang, echoing, in the air between them.

Helen was not a virgin, but never in the course of the single, bashful relationship she had known had there been an instant like this. Half of her, astoundingly, wanted to say – just as casually – yes, let’s do that. But it was a hidden half that she was far from ready to reveal, even to herself. The practical, careful Helen of old, the one who took stock and who watched intently from the sidelines, was the one who answered.

‘No,’ she said, as if considering it. ‘Not yet.’

‘Yet?’ Irritation flickered in Oliver’s blue eyes as he stared at her. He seemed to see her, very close at hand, yet not to notice her at all. ‘What can you mean, yet?’

‘People,’ Helen told him mildly, ‘usually leave a decent interval between meeting and going to bed.’

Oliver’s quick, sardonic smiled surprised her. ‘A decent interval, then. How many days? How many dinners? God, I hate waiting. And I hate decency even more. It’s a proletarian idea, hasn’t anyone told you that?’

Helen was stung. She jumped up from the cushions, and as she moved she saw Oliver’s eyes on the length of thigh showing beneath her scarlet hemline. Her blush deepened and she lost the sharp retort which had been ready. Oliver stood up too, grinning, and then swung her round by the shoulders. His mouth found the nape of her neck under the black curls and he kissed her.

‘Ah, a warm place at last,’ he teased. ‘You’re dressed to look like a flame, but your skin feels as cold as marble. Funny girl.’ Then he turned her round to face him and kissed her mouth, deliberately, still smiling against her closed lips. ‘Don’t worry. If you prefer decency, we’ll let it lie for now, like a fat bolster between us.’ The good humour in his voice changed everything for Helen. He did understand, then. The sensitivity she had guessed at was there in him, waiting. Helen stood in the circle of his arms for a second and wished that it was all different. If she had said yes … If she had been a different person.

Flora or Fiona would have said yes, and they would have been able to keep him for a while. And now he was moving away from her, disentangling himself as he had done from the blonde Vick. Oliver.

‘Come on,’ he said kindly. ‘I’ll walk you back to Follies. I’d like to drop in and see old Rose for half an hour before Hall.’

Helen nodded dumbly. As they walked together across the Quad the ancient bell, Great Tom, struck six. The long, tolling notes lapped sonorously inside her head, uncomfortably like a knell. Yet Oliver drew her arm snugly through his as they turned down St Aldate’s. He was whistling softy, a single phrase over and over again, as if he was trying to tease the rest of a forgotten theme out of his subconscious. Helen fell into step with him, half carried along by the support of his arm. He was wearing a shabby, brown leather aviator’s coat with a lining of tightly curled sheepskin, and in the warmth of a deep pocket his hand still held Helen’s. Remembering the first of his questions, she knew that this was a moment she would like to freeze for herself. If only it was possible to keep him here, beside her, just like this.

When they reached Follies Oliver handed her elegantly down the steep stone steps to the island, walked up through the silent house and stopped outside her door. His eyes glowed very bright and amused in the darkness.

‘I’ll be back,’ he told her, ‘to check out the bolster before too long. Such uncomfortable, old-fashioned things.’

‘That’s good,’ Helen responded equally brightly. ‘I shall look forward to that.’

Oliver raised his arm in a half wave and turned away again. Helen stood listening until the sound of his footsteps had been swallowed up in the recesses of the house. She heard a burst of radio music followed by a door closing, then silence. The thought of her own cold, empty room was uninviting. Helen slipped down the stairs to the grander spaces of the gallery below.

‘Come in,’ Chloe’s low, musical voice answered her knock at once.

Chloe was sitting curled up in her armchair in a pool of lamplight. There was a red-embered fire burning in the grate and her hair was glowing even brighter in the double warmth of the two lights. She closed her book with an exaggerated gesture of relief and grinned up at Helen.

‘Well, and how did it go?’

It was easy to tell Chloe things. Helen clasped dramatically at her heart and stumbled forward into the light. ‘Wonderful. And awful. He asked me to go to bed with him and I said no. Oh God, Chloe, what shall I do?’ It was half a joke, but only half. Something intriguing had come in to fill a cold, empty space inside Helen, and now she didn’t want to let it go.

Chloe’s eyebrows lifted a fraction. ‘Horny little bugger,’ she said, amused. ‘You were quite right to tell him to get lost. He’ll be back, love, don’t you worry.’

‘I hope you’re right,’ said Helen softly. ‘I want him to be back, very much.’ She didn’t, in her preoccupation, see the quick anxious glance that Chloe shot at her.

After an hour of sitting with Rose in the impenetrable untidiness of her kitchen, Oliver stood up restlessly. He drank the remains of the dark brown sherry in his glass and made a face. Rose went on impassively with her sewing, not looking at him. ‘Before you go,’ she said, ‘what are you doing to that nice little thing upstairs?’

Oliver shrugged himself into his coat without answering, turned to go, and then as an afterthought sketched a kiss in the air between himself and Rose. ‘Doing nothing at all, darling Rose. All the treasures are kept securely locked away, as you must have guessed. Bloody boring. And now, au revoir or I shall be late for Hall.’

Rose, left alone in the kitchen, smiled a little and went on sewing.

Oliver took the steps into the misty dampness shrouding the city two at a time. He noticed the outline of a big car parked on the bridge as he came level with it, then as he swung out on to the pavement he saw that it was a white Rolls. Beside it, a man in a peaked cap was lifting a heavy trunk. Three other people were standing close together in the orange glare of the street lights, moisture from the mist beading brilliantly on their hair and clothes. The tallest was a thickset man in an expensive overcoat; one of the two women was clinging affectedly to his arm.

But it was the other woman who drew Oliver’s startled attention.

She looked very young. Over a cloud of pure white fur, the face was as innocent as an angel’s, and as expressionlessly beautiful as if carved in marble. Oliver stopped dead. At once, the face burned itself into his memory. He knew that he had never seen it before, yet it was familiar, even down to the faintly startled reflection in the depths of the immense eyes. And the girl went on looking back at him, her lips slightly parted and the street lights darting jewels of dampness among her snow-white furs.

The thickset man made an irritable sound and Oliver wrenched his attention from the girl.

‘Can I help?’ he asked politely.

The man stabbed a finger towards the square black bulk of Follies House.

‘Is this Follies House?’

‘That’s right.’

‘Jesus, will you look at those steps!’ The accent was mid-Atlantic, but beneath it were the unmistakable echoes of London’s East End. Hobbs, can you get all this down there?’

The chauffeur leaned over the parapet. ‘Yes, Mr Warren, I think so.’

The other woman clung more tightly to the cashmere sleeve. ‘Oh, Masefield, it’s so wet out here. My hair.’ Without a word her escort opened the passenger door and handed her back into the Rolls. Hobbs bent to lift the trunk again. The girl stared back at Oliver, motionless. The shroud of mist seemed to swallow all the sounds around them, so that they moved in eerie, silent isolation.

‘Can I help?’ he asked again, but the thickset man glanced at him only briefly. ‘Thanks. No.’

The girl in white ducked her head and followed her father down the steps. Hobbs bent to the trunk again and bumped awkwardly after them. The woman sat in the car, staring ahead of her and rhythmically stroking her hair.

Oliver walked away, back up St Aldate’s to Christ Church. He whistled to himself as he went, the same few, unfinished notes. Now he knew. The man was Masefield Warren. More, the white girl was his daughter, Pansy. Her face, wide-eyed and startled, was familiar from the flashbulb shots of a hundred gossip columns. Pansy Warren was not only beautiful, she was the heiress to her father’s by now uncounted millions.

As Oliver walked back under Tom Tower the rest of the little whistled tune came spilling out, unchecked.