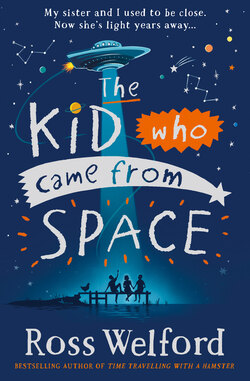

Читать книгу The Kid Who Came From Space - Ross Welford - Страница 8

Оглавление

My twin sister Tammy has been missing for four days now, so when the doorbell goes, I assume it’s the police, or another journalist.

‘I’ll get it,’ I say to Mam and Dad.

Gran is asleep in her tracksuit on the big chair by the Christmas tree, her head back and her mouth open. The lights on the tree haven’t been switched on for days.

I open the door and Ignatius Fox-Templeton – Iggy for short and for slightly less weird – stands there wearing a thick coat, a flat cap and shorts (despite the snow). He’s holding a fishing rod in one hand and Suzy, his pet chicken, under his other arm. A large bag is slung over his back and his rusty old bike lies next to him on the ground.

For a moment we just stand there, staring at each other. It’s not like we’re best friends or anything. We had this sort of awkward encounter when Tammy first went missing on Christmas Eve. (I nearly broke his mum’s fingers with the piano lid, but she was OK about it.)

‘I, erm … I just thought … I was wondering, you know, if … erm …’ Iggy’s not normally like this, but he’s not normally normal anyway, and besides, nothing’s normal at the moment.

‘Who is it?’ calls Mam from inside, wearily.

‘Don’t worry, Mam. Doesn’t matter!’ I call back.

Mam has been getting worse in the last day or two. None of us has been sleeping well, but I’ve begun to think that Mam has not been sleeping at all. She’s got these blue-grey patches under her eyes, like smudged make-up. Meanwhile, Dad has been trying to keep busy at the pub and coordinating search efforts, but he is running out of things to do. Everyone wants to help us, which means the only thing left for us to do is to sit around and worry more, and cry. Sandra, the police Family Liaison Officer who has been here a lot, says that it is ‘to be expected’.

I turn back to Iggy on the doorstep.

‘What do you want?’ I say, and it comes out blunter than I intended.

‘Do you … erm, do you want to go fishing?’ he almost whispers. His eyes blink rapidly behind his thick glasses.

In case you don’t quite get just how odd I find this, you have to know that for the last few days the only world I have known has been one of worry and tears; and police officers being brisk; and journalists with cameras and notebooks wanting interviews; and people from the village bringing food even though the pub has a massive kitchen (we now have two shepherd’s pies and a huge pavlova); and Sandra, Dad and Mam trying to manage all of this with Gran; and Aunty Annikka and Uncle Jan flying in yesterday from Finland because … well, I don’t really know why. To ‘comfort’ us, I suppose.

All because, four days ago, Tammy vanished off the face of the earth. Nothing has been right since.

So when Iggy turns up wanting to go fishing, my first thought is: Are you mad? Then it dawns on me.

‘Is this Sandra’s idea?’ I ask, holding the front door half closed to keep the cold out.

Iggy doesn’t seem to mind. He gives his characteristic confident nod. Iggy knows Sandra already: he’s had several reasons for a police Family Liaison Officer to call at his house.

‘Yes. She thought you might want to get out of the house for a bit. You know, change of scene, and all that malarkey. Think of something else.’

Malarkey. It’s a very Iggy sort of word. He doesn’t have much of a local accent, though he’s not exactly posh either. It’s like he can’t quite decide how his voice should be and uses odd words to fill the gaps.

He goes on: ‘And so, here I am!’ He holds up his fishing rod. ‘Well,’ he adds, nodding to Suzy. ‘Here we are.’

I’m really not sure about Iggy. Dad doesn’t like him at all, ever since – soon after we arrived in the village – Dad caught him stealing a box of crisps from the pub’s outhouse. His mum said the outhouse should have been locked, so Dad’s not keen on his mum either. She keeps bees. She’s divorced from Iggy’s dad, I think.

Still, I have to admit: what Iggy is doing is quite kind, even if it wasn’t his idea. I don’t even like fishing. Suzy, Iggy’s chicken, stretches out her neck for a scratch, and I oblige, burying my fingers deep in her warm throat-feathers. To be honest, I have my doubts about Suzy too. I mean, who has a pet chicken?

Then, as I tickle Suzy, I think: What’s the worst that could happen?

So I put my head round the living-room door. Dad has gone into the kitchen on his phone and Mam is just staring blankly at the television, which is switched off. Gran snores a bit. The room’s far too hot and the remnants of the fire in the wood burner glow white-orange.

‘I’m just going out for a bit, Mam,’ I say. ‘You know – fresh air, an’ that.’

She nods but I’m not sure she completely heard me. All that’s in her mind is Tammy.

Tammy, my twin sister, who has disappeared off the face of the earth.