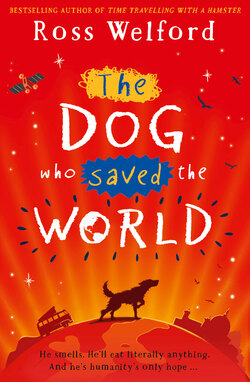

Читать книгу The Dog Who Saved the World - Ross Welford - Страница 20

Оглавление

Up till recently, I’ve hardly seen Clem for weeks, it seems. He’s finished his exams so isn’t back at school till September. He was supposed to be going to Scotland with his friends, but it all fell through when one of them got a girlfriend. So he hasn’t got much to do before we all go to Spain later in the summer.

For the last couple of weeks, he has occupied himself by messaging people, listening to music, helping Dad in his workshop and growing a patchy beard. He now looks about twenty.

The thing is: I miss him. Something happened to Clem maybe a year ago. The brother I grew up with – the boy who played with me when I was tiny, who let me ride on his back for what seemed like hours, who lied for me when he didn’t have to when I left the tap on and the bath overflowed, who told me his screen login so I could watch stuff when Dad said I couldn’t, who once laughed so hard at my impression of Norman Two-kids at the corner shop that he fell off the bed and banged his head …

… that boy had moved out of our house.

In his place came a boy who looked exactly the same, but behaved differently. A boy who hardly smiled, let alone laughed. A boy who wanted to eat different food from us and, when Dad refused to cook separate meals, got shouty; a boy who could spend a whole weekend (I’m not joking) in his room, emerging only to go to the toilet; a boy whose response to pretty much everything was to roll his eyes as if it was the stupidest thing he had ever heard.

Dad said it was ‘normal’.

But … there was one good thing about Clem changing, and it was this: I think I succeeded in persuading him not to tell Dad about Dr Pretorius, and it was all down to his beard. Sort of. Let me explain.

He was full of questions, and the main one was, ‘Why is she so secretive? If I’d invented something like that, I’d want everyone to know.’

‘I don’t know, really. She says she’s got something even better to show us soon, but right now I think she’s probably scared that someone will steal her idea.’

And then I added something that – not to sound boastful or anything – was utterly and completely brilliant, and I didn’t even plan it. I looked at the floor, all sorrowful, and said, ‘I know it was wrong, Clem. I really should have told a grown-up. But … I think you probably count as that now?’

Clem took off his spectacles and held them to the light to check for dirt and smears. It’s something he does a lot. ‘Perfect vision required, eh?’ he said, obviously flattered by me calling him an adult, and I nodded.

‘So she says. It’s why she can’t test it herself.’

‘She’ll need to sort that out if it’s to be commercial. Two-thirds of people wear specs, you know?’ He picked up a spanner from the bench and turned back to the rusty old campervan that he and Dad had been working on, which meant our conversation was over.

‘You won’t tell Dad?’

‘Not for now. But be careful.’ He actually sounded like a grown-up then.

Now I could worry about something else instead. The vicar had said Ben was sick. What was that all about?

Everything, as it turned out.