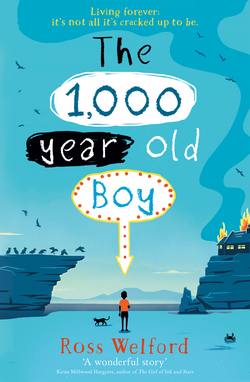

Читать книгу The 1,000-year-old Boy - Ross Welford, Ross Welford - Страница 18

Оглавление

Einar of Gotland was unrecognisable as he stood on the wooden jetty of Ribe on the west coast of Denmark with Hilda, his wife, and a small child – me. That was exactly what he wanted.

He had shaved his beard, cut his hair and dressed in the clothes of a middle-ranking tradesman. Not too rich to attract attention, nor so poor that people would question his ability to pay for a passage on the ship to Bernicia in the land of the Britons.

No one knew him in Ribe, but he was taking no chances. We stayed a little way out of town. Da was on edge, said Mam. He thought he was being followed. Hilda was now a Neverdead as well, the bloody process carried out on the night of their marriage. Together they would live forever in the new land with their son.

If they made it.

Einar had bought passage on a cargo ship that would sail straight across the North Sea, stopping first north of the old Roman Wall to offload cargo and take on another shipment, and then carrying on down the coast to the mouth of the Tyne.

The captain had said four days, maybe five, depending on the wind – and the wind was not cooperating. Cargo ships relied on sail, rather than the oars that the longships used, so if the wind was coming from the west – as it usually did – a journey to the new lands was hard sailing.

After a week, the wind changed and in less than a day the battered old knarr, with its filthy, patched sails, and old, tarry ropes, was gliding out of Ribe harbour.

Da boarded separately from Mam and me. We were to pretend for the whole journey that we were unconnected. Da gave the pearls to Mam, to keep them even safer, in case anyone recognised him. ‘Until we land,’ Mam had said to me, with her most serious face as she put it when retelling the story, ‘you must never speak to your da.’

She said I was clearly puzzled but did as I was told. I was always a good, obedient boy, she said.

We had very little luggage: a bag each, made of hemp, and, for me, a wicker basket containing a young cat that I had called Biffa. It was not a name, nor even a word. I think I just liked the sound of it.

On the boat there was no privacy. If anyone needed to wee, or more, they had to do it in the sea, as the boat shuddered along over the cloud-coloured waves. The crew were not fussy: they just dropped their trousers and put their bottoms over the side of the boat.

And that is how we lost Da, said Mam. No one saw him go. The wind had come up, and the skipper had pulled in the sail, and the long knarr was rising and falling on the swell. As the boat bucked and reared on the white-capped waves, Da got up and clambered to the rear, which was where everyone went. It was a little bit private as there was a stack of barrels secured with rope that would give you some cover and you could hang on to the rope straps.

And that was it, the last anyone saw of him.

Mam was the first to notice. Everyone had been huddled over, trying to stay dry, when she said, ‘Where’s Einar?’

When it became clear what had happened, the skipper turned the boat into the storm and tacked to and fro, going back way further than we had come that day, in case Da had been carried on the current. There was no sign of him. Even if he had yelled when he went over, he probably would not have been heard over the noise of the waves and the wind and the creaking old boat.

What a way to go. It still makes me sad, even though I can hardly remember him, and this was centuries ago, but it still comes back to me, even after all the sad and bad things that I have seen.

‘The hardest thing,’ said Mam, ‘was being unable to grieve. I had to pretend to be as sad as someone who had only just met him – and that you were crying because you were small, and any death upset you, not because your father had gone missing.’

‘But why?’ I used to ask.

‘Because that was the plan, to avoid those who might be after the pearls. And I stuck with it. I did not know – I still do not know – if he was pushed overboard. There was another passenger on the boat: a mean-looking devil with a huge black beard, and he and your da had argued earlier that day. I know Einar did not trust him. When you cried with the cold, he told me to, “Shut that bairn up!” and when you howled for the man who had gone overboard – your da, though no one knew it – he threatened to throw you over to join him.’

If I close my eyes, I can remember that face, inches from mine, growling, ‘Holl munnen!’ to a grieving infant. ‘Shut your mouth!’ The memory can still make me cold.

And so, six days later, freezing cold, soaking wet and smelling strongly of sheep’s cheese, sealskins and ship’s tar, Mam and I sailed up the Teen and got out of the boat on the long wooden pier by the fishing huts.

She had set off from Denmark as a young wife, and arrived in Teenmooth a widow, with a young, fatherless child.

Little. Old. Me.

Then, more than a thousand years later, a tiny little girl fell into our yard and banged her head. That was when everything changed.