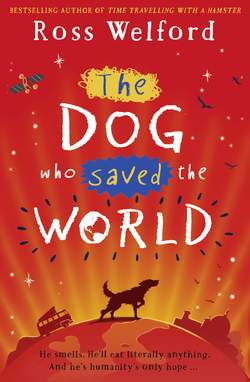

Читать книгу The Dog Who Saved the World - Ross Welford, Ross Welford - Страница 18

Оглавление

It has become a big thing in the last year or two: Disease Transmission Risk. At school it’s DTR this, DTR that, and the only good thing about it is that you only need to cough in class to get sent home.

Last year, every classroom at Marine Drive Primary had a hand sanitiser installed by the door. I think it was a new law.

So one of my jobs when I’m at St Woof’s is the maintenance of the sani-mats and hand-sans in the quarantine area. The sani-mats are wet, spongy mats that clean the bottom of your shoes when you go in and out of the quarantine area, which is where dogs go when they’re sick.

Anyway, it all happened a few days after our first visit to Dr Pretorius and the Dome.

I had topped up the disinfectant in the sani-mats first, then I went into the quarantine section to see Dudley, who had a tummy bug. It wasn’t his first time there, either, so I wasn’t especially worried. If you remember, he’d been gnawing on a dead seagull at the beach, and I thought that might have been the cause.

He was behind a fence of wire mesh that comes up to my chin. There were wellies and rubber gloves by the entrance gate, which I put on before I went in. He wagged his bent tail weakly.

‘Hello, you funny old thing!’ I said. ‘Are you feeling better?’ Normally, I’d let Dudley lick my face, but we’re not allowed to do that with the quarantined dogs, so instead I gave him a good old tickle on his tummy. It wasn’t quite the same with rubber gloves, but he didn’t seem to mind.

A family had been in to see him a few days before, perhaps to adopt him, but I think he was just too odd-looking.

‘The little girl thought he was cute,’ said the vicar, ‘and she said something to her mum in Chinese. Then they all had a long conversation which I didn’t understand – except the dad was pointing to Dudley’s eye, and his teeth and his ear, and then they left.’

Poor, ugly Dudley! I thought of the little Chinese girl falling in love with him and then her dad saying he was too strange-looking.

Secretly, though, I was very relieved. I know it’s better for a dog to be with a family rather than in St Woof’s, but I couldn’t bear it if Dudley was adopted.

I looked at him carefully. He didn’t seem very well, poor doggie. He hadn’t eaten much of his food, but he had drunk his water and done a poo in the sand tray, which I washed out and sanitised, and I did everything right, exactly according to the rules. Then I threw his soggy tennis ball for him a little, but it didn’t excite him very much and anyway I bounced it too hard so that it went over the fence and rolled away and we had to stop.

I was coming out of the quarantine area, I’d done the sani-mats and I was about to do the hand-sans (which were empty) and who was standing there but Sass Hennessey. She did this little hair flick and stood with one hand on her round hip.

‘Hiiiii!’ she said but there was zero warmth in her eyes.

‘Hello, Saskia,’ I said.

‘I was just saying to Maurice that he’s got the place looking really smart now,’ she said.

Maurice? Maurice? Nobody calls the vicar Maurice, apart from my dad who’s known him for years. Everyone else calls him vicar or Reverend Cleghorn. It was so typical of Sass to call him by his first name, though. I was annoyed already, and what came next was worse.

‘That ugly old mutt in there,’ she said with her head on one side, all fake sorrow. ‘It really would be kinder just to put him down, don’t you reckon?’

That was it: the mean comment I mentioned before. It took me a few seconds to realise she was talking about Dudley. Dudley – my second-favourite dog in the whole of St Woof’s! I could feel my jaw working up and down, without any sound coming out.

‘Are you OK, Georgie?’

‘Yes, I’m fine, Sass.’ But I wasn’t. I was furious. In silence, I refilled the hand-sans, removed my gloves and put some of the gel on my hands, rubbing it in angrily while she just stood there. Then I took off the wellies.

‘Look, I didn’t mean …’

‘You know we don’t do that here. So why did you even say it?’ I was furious.

‘But if he’s very ill and old …’

I snapped, loudly: ‘He’s not that ill and he’s not that old. All right?’

I could tell Sass was a bit taken aback. She said quietly, ‘Ooo-kaaay,’ and I thought for once I might have got the better of her.

She bent down and gingerly picked up Dudley’s spit-soaked ball that had rolled towards the door. She handed it to me and I was forced to say ‘Thanks’. It was an odd sort of peace offering.

I turned the ball over in my hands as I watched her walk away, and then tossed it back to Dudley, shutting the quarantine door behind me.

I was still cross when I got back to my station. Ramzy was waiting for me, and he was holding Ben, the snarly Jack Russell, who was trying to lick his face.

‘Look!’ he laughed, dead proud. ‘I’ve made a friend!’

‘So you have,’ I said. ‘Good boy, Ben,’ and I let him nuzzle my hand. Then I went round the rest of the dogs in the station, giving them a final stroke before I left.

‘Bye, vicar!’ I said, pulling on the big door.

‘Goodbye, Sergeant Santos and Private Rahman!’ said the vicar, giving another salute. ‘Jolly good work!’

So that was it. Damage done. I had started the End of the World.

Obviously, I didn’t know it at the time. I’ve kept the secret till now: how I handled the tennis ball that was infected with Dudley’s germs, germs that he had picked up from the little girl who had wanted to adopt him. I then passed on the infection to poor Ben by letting him lick my germy hands, and then to the other dogs …

Turns out that all the DTR lessons in the word can’t stop someone being stupid.

Or – for that matter – being so furious at Sass’s mean comment that my mind was all over the place. Which amounts to pretty much the same as being stupid.