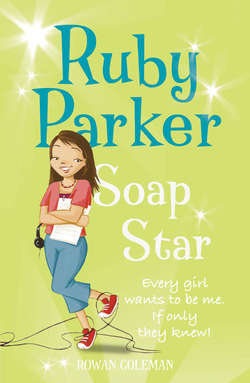

Читать книгу Ruby Parker: Soap Star - Rowan Coleman - Страница 10

Chapter Six

ОглавлениеI knew when I went down to tea that I was going to have to be as brave as Lucy, maybe even braver. It was bound to be bad because Mum made chicken risotto, and she only ever makes that when we have guests or if I’m sick or something, because it takes her hours and she has to stir it until her wrists go funny. I sat at the table and watched her stir and stir, her face tipped down into the steam as if she could see something else apart from risotto in the saucepan. Everest sat at her feet and gazed up, trying his best to psychically levitate some of the chicken out of the pan and into his paws.

“What is it, Mum?” I finally asked her. I was pulling my fingers through my hair, which, although it smelled nice, was not any blonder than it had been this morning. Mum looked up at me and smiled, but it was one of those upside-down smiles that are really more like frowns. Like a mixture of both the comic and the tragic mask in the school badge.

“Dad’ll be here in a minute and then we talk about things,” she told me carefully. “We just need to talk about things, Ruby, about how things are at the moment and how things are going to be.” I felt my stomach knot up and tighten again. When she said “things” she meant us, she meant me and Mum and Dad and how we were going to be.

“Things are fine, though,” I said, trying to stay casual, as if a nameless dread wasn’t beginning to boil up again in my tummy. Gradually, in the garden with Nydia, in the middle of our film, in the middle of the jungle with Justin swinging me through the trees on vines to save us from giant man-eating ants, my tummy knots had untied themselves and gone away. I told myself, and so did Nydia, that I’d been worrying over nothing – that I was over-imagining the way I was feeling again, and getting everything out of proportion, like I did when I thought this lump on my foot was cancer and it turned out to be an insect bite. But even if it hadn’t been for the chicken risotto, I knew that what was coming was bad when I heard Mum’s voice. When she spoke her voice sounded as if it was stretched very, very thinly, as if she were speaking from a very long way off.

Another universe, practically.

And then Dad came in and Mum went sort of stiff and nobody looked at me for a long time. They went about just doing normal stuff, only it wasn’t normal because normally they weren’t ever in the same room as long as this. Dad hung up his coat and took off his tie. Mum put out the cutlery and poured out drinks and didn’t ask me to do anything – so definitely not normal. And neither one of them told Everest off for sitting right wherever it was they were trying to walk and for making them trip and stumble. Dad didn’t even tell me his joke of the day. They just moved around like robots.

Then we all sat at the table and Mum put out the food. I looked at it steaming on my plate; it looked delicious, but somehow not real and I couldn’t eat any. My stomach was too full up with worry.

“Ruby, do you want some…” Mum passed me over the cheese, but I pushed it away. I couldn’t stand this abnormal normalness for a minute longer.

“Just say it!” I snapped at her. My words popped the clingfilm of tension that had suffocated the room and suddenly the kitchen was crowded with emotion. “Just say whatever it is you’re going to say. Please. Just say it.” I felt frightened then, and very small. Mum and Dad looked at each other and there was a moment of silence. I felt Everest come and sit on my feet: his fat, warm body made my toes tickle and I told myself it was because he was on my side and not because he was just after scraps.

“Well…” Mum almost looked at Dad. “You tell her, Frank, I think that – well, I think it’s you that should tell her.” The way my dad looked at my mum then – I’ve never seen him look at her like that before, or anyone. He looked at her as if he didn’t even know her, like she was just some strange woman in his house telling him what to do. He looked at her as if he didn’t like her, not even a little bit.

“Ruby, you know that things have been difficult at home for a while, don’t you…” I shook my head vigorously; just like Mum he was talking about “things” again. I wanted to ask him, why didn’t he say what he meant? Why didn’t he talk about me, Mum, us? We’re not “things”, we’re living, breathing people.

“No. No, I don’t know that. I think THINGS have been fine. Really fine,” I said. “So don’t worry about me, I’m fine. Is that all?” Dad bit his lip and took a breath. He picked up his fork and put it down again. Then he swallowed as if someone had made him take some really bad medicine. I watched his face for any sign of what it was he was about to say, but it was almost as if my dad wasn’t in there.

“Ruby, I’m sorry,” he spoke at last. “Your mum and I, we don’t get along like we used to. We’ve been making each other…unhappy…for a long time now.” My mum huffed out a breath of air as if “unhappy” wasn’t nearly a good enough word to describe how my dad made her feel. I looked at them both, from one to the other. My mum and dad: the two people who put me here in the world. It was them loving each other in the first place that made me happen. If they hated each other, then what about me? Did they hate me too? I tried to make them see.

“Are you sure?” I said quickly. “Because I don’t think you’re as unhappy as you think you are. I mean, when you say a long time, how long do you mean? We were happy at Christmas, weren’t we? And that’s only a few months ago. We were happy on holiday. We’re happy every day, aren’t we?” Neither one of them would look at me. “Well, aren’t we?” I pressed on. “It’s about working it out, isn’t it? And anyway, you don’t make each other unhappy because, Mum, Dad got you that perfume you really wanted at Christmas, didn’t he? And you were happy that day, weren’t you? And you’re happy when Mum makes a big roast, aren’t you, Dad? You love a big roast, don’t you?” Mum looked at her hands.

“Well?” I said to them both. Mum reached across the table and picked up my hand, her skin felt hot and dry.

“We were, darling, but you’ll understand this better when you’re a bit older. Being happy for one day a year, or just sometimes – it’s not enough.” She screwed her eyes shut tightly for a second and then looked at me. “And sometimes…sometimes it’s easier to pretend to be happy.” I shook my head in disbelief. Mum was holding my hand, but it felt like I was slipping away from her, from Dad, from everything I knew and trusted about my life and into an unknown darkness.