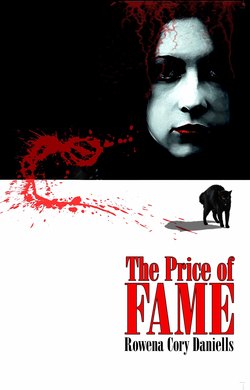

Читать книгу The Price of Fame - Rowena Cory Daniels - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 2

Оглавление'Whoa!' Monty edged closer, hands lifting to calm me.

I backed off, stomach cramping. One of the bench stools hit the back of my thighs and I felt trapped. This was an ideal time to practise my meditation. Naturally, I couldn't. But I was not going to have a panic attack. I hadn't had one for five years and I was not about to start now.

'Whoa, just an idle question, Antsy.' His voice was deep and soothing.

It did calm me and, against my will, I had to smile. 'What are you, the Horse Whisperer?'

A bark of laughter escaped him. 'I love it when you do that. You're the only person I know who can get one jump ahead of me.'

Really? I studied his face, I realised I liked making Monty laugh.

'Didn't mean to upset you, Antsy.'

No, and I didn't want to brush Monty off. The silence stretched. I placed my heel on the stool crossbar and sat on the seat, putting more distance between us. Showing more thigh than I intended. I resisted the urge to pull the skirt down. 'So how did you find out about my project?'

He accepted the change of direction gracefully. 'I dropped in on your nan.' A rueful grin lit his face. 'She ended up inviting me to dinner.'

I rolled my eyes. The thought of Nan serving Monty roast lamb and potatoes made me smile. It would probably feel just like home to him. But… 'Nan's moved from the old house.'

'Exactly.' He rested one elbow on the bench, long limbs casual. 'You're a hard person to track down, Antsy. Even Merryon didn't know where you were, but she did give me your nan's new address. She said you were preparing a doco and told me where you were staying. I know what happened in this house and you never made a secret of your obsession with the Tough Romantics, so I put two and two together. I want in.'

I was not obsessed, but I let it slide. I felt I had to be honest. 'I'm financing everything from the sale of the family home. It may never get off the ground.'

'It will. Somehow. You've got a knack for bringing people together, bringing out the best in them. And, if we don't get backing, it'll be just like old times, working with friends, sleeping in the back of cars. I do my best work like that.' His black eyes challenged me.

Monty was afraid I'd turn him down. He needed something from me. Now that was novel.

I slid off the stool, took a step forward and shoved him in the chest. 'You're a pushy bastard.'

A grin ignited him. 'And you're a slave-driving bitch, but here I am. Yours to command.'

I took a step back, bumping into the stool. Was there a sexual connotation in that, or was it just me getting the hots for a younger man? Did I mention Monty has the most beautiful body? He could have modelled for Michelangelo's David. Not that I would lust after someone simply because of their body.

When I first met Monty I assumed that he was gay and hadn't realised it yet. You know, good looking guy, dresses well, able to hold an intelligent conversation - has to be gay. But halfway through second year he turned up with a lady friend. Sacha was no girl, she was 30 if she was a day. And Monty was just 21. Five feet tall with curly dark hair, Sacha bristled with intelligence, always debating politics, art and philosophy. She irritated me, too pushy, but the rest of the gang liked her. In the 18 months that they were lovers Monty acquired a whole new layer of sophistication. The girls in our group whispered he'd also become the consummate lover.

My cheeks grew hot. I knew the blush had to show. I hated being so fair. I was glad of the high-backed stool between us.

'Okay, you're part of the project. Open the wine.' I went around to the cutlery draw, found the corkscrew and slid it across the bench to him. He collected the wine and came around to stand over the sink next to me. I felt a physical awareness, a tug that did not bode well for my peace of mind. So I looked for a distraction and remembered the cat.

Grace and Scott had been so excited about their first overseas trip, when we'd met to do the house handover, that they'd forgotten to mention their cat. I'd gone to bed and, next morning, there it was at the back door meowing. I loved cats, but they didn't love me. One cuddle and I was a sneezing, wheezing wreck. But I let it in, gave it some milk and water and later bought some dry cat food. I'd named him Smokey, since he was so dark he was almost black.

So, now I went to the pantry took the crunchy cat food, and topped up the food and the water bowl leaving them just outside the back sliding door, calling, 'Smokey, here boy.'

No sign of him.

Feeling more in control, I closed the sliding door and went over to the kitchen table leaning my hips on it. 'You're wrong, Monty. I'm not obsessed with the Tough Romantics. This doco is a carefully reasoned attempt to make a name for myself. I've roughed up the first draft of the script. Today, I saw Arthur Davidson, and I've spoken with Tucker's PR woman. I'm hoping to catch Pia sometime soon. She's in Australia for a family wedding.' I threw that in, trying to impress him but it was water off a duck's back.

Monty always was a good poker player. He'd had everyone in our group bluffed. Everyone but me. Being so much older and divorced had given me an advantage back then. Still gave me an advantage a 25-year-old lad.

His large hands made the wine bottle look small but he wasn't clumsy. I'd seen him dance. It was pure invitation. Yes, I definitely appreciated Monty - in the same way I appreciated the leaves on Arthur's driveway. Beauty for its own sake. Well, maybe there was a little lust in there, but Monty didn't need to know that.

'What's your angle on the band?' he asked.

'I'm not sure.' I went to get the wine glasses. 'I know what I don't want to do. I don't want to milk it for sensation. The Tough Romantics weren't some manufactured pop group. I want to do them justice.' We were just kids. I heard the echo of Arthur's voice. We were boring little shits. 'I want to look at the dynamics of the band in their formative years. Only the people who were there can give us the real band.'

'And the real murder? With everything that was written at the time you'd hardly need to interview people about it, 25 years on.' Monty said. 'Shit. That taxi driver was sick. Claimed he was innocent all along, then went and killed himself. What does that tell you?'

I hesitated. You never knew with Monty. He liked to argue black was white for the pure enjoyment of it. At the time of the murder, nearly everyone had been convinced of O'Toole's guilt. His suicide, a week to the day, was the nail in his coffin. As a child I'd thought so too. But, since beginning my research, I'd begun to wonder. O'Toole was too damn convenient.

'A fingerprint expert said O'Toole's prints, which the police claimed to have taken from the knife hilt, couldn't have been from it. Something about the curve of the surface and the texture.'

Monty's black eyes caught mine.

'I'll hunt down the clipping for you. In fact, if you're really interested, I can give you the whole file,' I said, watching him ease the cork out of the bottle. He poured the wine, pushed mine across the bench towards me. I had to come closer to get it. He lifted his glass. I let mine chime against his, the bench between us. If I wanted to work with Monty I had to be ready to ride the tiger.

'To the series!' he said, his voice rich and deep. 'May it be the first of many and make us a mint!'

'That's an about-face,' I teased. I took a mouthful of wine, savoured it, then swallowed. 'I thought you were morally opposed to mercenary motivation?'

'Since graduating I discovered I'm morally opposed to being unappreciated and kicked around,' he said, eyes intense and imperative. 'I want a chance to do some really good work and you're going to give it to me. I'm gonna ride your comet to the stars, Antsy. I can smell the stink of success on you.'

I chose to believe Monty meant it as a veiled compliment.

Now he drained his glass with relish and poured another. I covered mine when he tried to top it up. Monty had an amazing capacity for alcohol, but I didn't. Two glasses and I'd curl up and go to sleep. At least I wasn't a two-pot screamer, as Nan would say.

'So who has agreed to be interviewed?' Monty asked, gaze sharp as razors.

'No one. But I saw Arthur today.' I took another sip of my wine, felt it race to warm my empty stomach. Better slow down. I hadn't eaten since breakfast, hadn't had time. 'He refused to talk in front of his wife, then offered to put me in contact with someone from the band's early days.'

'Sounds promising.'

'And if he does come across, he can put us in contact with Pia. I get the feeling they are still quite close.'

'That makes two out of three. I'm thinking Tucker will drop his daks for you.'

'Tucker would drop his daks for anyone!'

Monty's eyes twinkled.

It was so good to be working again. To be working with Monty.

The smile slipped from his face and he leant forward propping his elbows on the bench. The reflected glow of the steel lit his features from below, filling his dark eyes with an evangelistic, silvery gleam. My heart raced. I loved it when Monty got inspired.

'Been thinking, Antsy. I brought my computer and my new digital camera gear. They're out in the van waiting for you to say yes.' He sent me a cheeky grin. 'Soon as you give me the go-ahead, I'll get started. I reckon with the software I've got I can create to-die-for effects, pull people out of old footage, digitise old stuff and clean it up. Whatever you want, I'm your man.' His eyes held mine for half a beat too long.

I felt my body react with a kick of arousal-induced adrenaline. That was a hit below the belt in more ways than one. The invitation was clear but there was no way I was going to be his sex buddy. I opened my mouth.

Before I could speak, Monty continued as if it hadn't happened, so I must have misread him. 'I'll start filming tomorrow, stuff we can edit for the Extra Features on the DVD.'

I laughed. My dream project was taking on a reality of its own, yet I felt an irrational twist of jealousy. Up to this point it had been my baby and now I resented Monty trying to muscle in. On a purely rational level there was good reason to welcome him - he was brimming with ideas, our areas of expertise complemented each other and I knew we made a good team. In my time at QCA I hadn't met anyone as focused on filmmaking as Monty. No one except me, of course.

'So how are you going to handle it?' Monty prodded. 'What's your doco's subtext?'

I shook my head slowly. 'I'm not sure. To tell the truth I'm not pleased with my rough script. The early band members haven't come alive for me yet.'

Veevie - Arthur's voice echoed in my head. It was like I heard him calling down the stairs to her, plaintive yet affectionate. Again, I felt that odd shift, registering it physically so that I shuddered.

'What is it?' Monty asked. 'You look like someone walked over your grave.' I could just hear his great aunts saying that.

Shrugging, I pressed the pads of my fingers into my closed lids - I would not scratch that scar - and chose to misinterpret his question. 'I just don't know. I thought I had a feel for the band, but the deeper I research, the more the individual members slip away from me. It's like they are based on shifting sands.'

'Let me read the script. That way, I can be thinking about art direction and hunt up locations while you research and write.'

We'd worked like this before, but I didn't want Monty seeing my weak first draft. When we'd made short films at QCA I'd always prided myself on writing scripts where the characterisation was strong enough to work on a stage without fancy special effects or car chases.

'I've only done a rough. Besides, I'm not sure what my hidden subtext will be.'

Monty studied me shrewdly. 'What's the matter? The idea is a winner.'

How could I explain my reservations when I didn't understand them myself? When I was on the right track I would know, and that sounded too New Age to confess to Monty. I looked around for a distraction.

The phone rang.

'If it's your nan tell her I miss her lamb roast already.' Monty's smile was sweetly innocent.

I picked up the kitchen extension. It was Arthur Davidson.

'You got a pen?' Arthur whispered. I had a vision of him hiding down the hallway from his wife.

'A pen? Just a sec.' I pointed to my satchel and Monty tossed it to me. I rummaged madly for a pen and a scrap of paper.

'Watched your DVDs, by the way. Liked your stuff.'

'I can do better.' I flushed. Great way to handle a compliment. Talk about foot-in-mouth disease. Normally I could lay on the charm, but this project meant too much to me. 'Right, got the pen, fire away.'

He gave me an address.

'Ah huh.' I was writing and nodding.

Then he dropped his bombshell. 'That's where you'll find Joe.'

I gave an undignified squeak that made Monty look over. Seeing my expression, he came to his feet.

Arthur kept right on speaking. 'I just got back from seeing him. He'll talk to you but I wouldn't hang about. He's just as likely to change his mind and do a midnight flit.'

My heart raced. 'Joe? You don't mean-'

'I mean the missing witness, Joseph Walenski. Joe, as in O'Toole's friend.' I could hear the smile in Arthur's voice.

'How'd you find him?'

'Bingo! You owe me one.' Arthur hung up.

I looked at Monty as I replaced the receiver. A buzz of excitement made my stomach knot.

'Well?' Monty pressed.

I waited a beat to draw it out, unable to keep the grin off my face. 'Arthur Davidson just gave us the missing witness!'

'Whaaat?' A frown spread across Monty's forehead. 'Why?'

I couldn't believe it. Never look a gift horse in the mouth, as Nan would say, but the police couldn't find Walenski 25 years ago, yet Arthur found him in less than a day. No, he already knew where he was. But how? And, as Monty said, why? Why give him to us?

'I just don't get it, Monty. Even if he was part of the '80s sex-and-drugs-and-punk-rock era, Arthur comes across as white bread now, so how could he know where Walenski lives?'

'Perhaps Arthur paid this guy not to come forward and testify 25 years ago. Perhaps he's been paying him ever since,' Monty suggested, leaning his hips against the bench and folding his arms across his chest. 'Clearing O'Toole might have implicated Arthur.'

'Then why give me Walenski now?' I countered. 'Besides, Arthur told the police he was down the road getting pizza when the murder happened and I believe him. I can't imagine him killing Genevieve, then calmly going out to buy pizza. He's not that cold-blooded.'

'It's always the least likely suspect who's the killer in Agatha Christie's books.'

I grinned. 'Wonder how Arthur found the missing witness.'

He shrugged. 'You can ask Walenski when we see him.'

'If we don't get over there soon he might do a runner.' I grabbed my coat. 'Then we'll never know.'

'And you couldn't bear that, could you?' Monty uncoiled, moving away from the bench.

I felt an answering coil in the pit of my stomach.

'Your car or mine?' he asked, double entendre intended.

I chose to ignore it. 'You navigate. I'll drive.'

'Then I'd better get the camera out of mine.'

'Whoa. Walenski's been Mr Invisible for 25 years. If we turn up on his doorstep with a camera he's likely to bolt.'

'You're right, but-' he hesitated.

I felt for Monty, the thought of capturing Walenski on film excited me too. 'Bring it just in case.'

Footscray was a run-down suburb across town. By the looks of things, it had inherited St Kilda's mantle. I counted three under-age prostitutes on one corner. My old Corolla wasn't worth stealing except for a teenager's joyride. I parked it under a street light to deter them. As I stepped out of the car, I was glad Monty was with me.

When I joined him on the footpath he'd turned up the collar of his leather jacket and tucked his hands in his pockets. He looked like he was waiting for a roving fashion photographer. I'd never been able to work out if Monty just naturally fell into these poses or if it was all carefully calculated. After all, he had an excellent eye for framing a scene. At any rate, I made a point of never commenting.

A drunk staggered past us, clutched the light pole and threw up in the gutter.

Monty gave a happy sigh. 'Feels just like home.'

I snorted. Monty and I came from a similar poor-respectable backgrounds. At least he knew who his father was and didn't have a heroin-addicted nutter for a mother. I elbowed him in the ribs. 'Keep your mind on the job. Look for 12B.'

There were no street numbers. We were not far from a dilapidated corner store, where a family business was struggling to compete with the nearest 7-Eleven.

'That's 10.' Monty indicated a little worker's cottage, then nodded to the store. 'So that makes the shop number 12.'

My heart sank. Was Arthur yanking my chain?

'Bet that's your man.' Monty pointed to a shadowy outline at the window of the residence above the shop.

Of course. We dodged the rubbish in the lane between the shop and the cottage, found a set of rickety stairs and climbed to the landing. Passing door A, we went on to B. The top screw had fallen off so that the B hung upside down. I knocked.

A knot of excitement curled in my stomach. I glanced at Monty. He had taken a step back. With the street light behind him his face was in shadow, expression unreadable.

'This could be an actor Arthur has hired to feed us a pack of lies,' Monty said softly.

'Arthur wouldn't do that,' I answered instinctively.

He snorted. 'The man's going into politics, Antsy.'

Damn, I'd always been too trusting, too quick to rush into things. Yet, I couldn't imagine Arthur telling a lie. Once elected, he was sure to shoot himself in the foot first chance he got. Why was he going into politics? 'Why would Arthur set us up?'

'To put us off the track.'

'Of?'

'The real killer.'

But we weren't trying to find who killed Genevieve, we were making a documentary about the band. That raised the question: did Arthur know who killed Genevieve?

I looked up at Monty. His eyes gleamed in the shadows.

Just as I went to speak the entry light came on, glowing through the rippled glass. Someone fumbled with the door, opening it as far as the chain would allow. An old man peered out at us. He had been taller than me but he was bent with age, and the flesh had fallen away from his skin, paring down his features to reveal the prominent nose and high cheekbones of a typical middle European profile. A sickly-sweet medicinal smell clung to his body and his clothes were shiny with ground-in grime. He looked genuine to me, but then he would, wouldn't he?

Arthur, a Machiavellian murderer? Logic told me it was possible but it just didn't gel.

The man claiming to be Joseph Walenski looked me up and down, registering surprise. 'You're the one? You don't look old enough to be a documentary producer.'

'I'm not. Not yet, anyway,' I told him. 'You're Walenski?' He nodded. 'I'm Antonia Carlyle, Arthur Davidson gave me your address. He said-'

'You didn't waste any time.' He cut me short as he closed the door to take off the chain, then opened it again and gestured us into a lounge room. 'Come in.'

When the light fell on Monty's face I saw the old guy react the way everyone did.

'This is just Monty. He's okay,' I said. 'He's my DOP, director of photography.'

Walenski's mouth twitched as if he fought a smile but he only nodded and stepped aside. 'Come in.'

But I didn't want to walk into that flat. The scar on my palm itched and a sick feeling settled in my stomach. The place felt claustrophobic. Stale air washed over me: onions, sausages, chips and something else, something I associated with Pop before he died. My great-grandfather passed on when I was seven yet I suddenly saw him vividly in my mind's eye, a grumpy old man, furious with the indignity of dying by degrees in hospital.

'Come in,' Joe repeated, directing us towards a narrow hall. 'This way.'

Rubbing my palm on my thigh, I stepped over the threshold and went down the hall to the living room.

I could tell the room had been nice once. There was a dusty, but fussily attractive, old-fashioned lampshade casting a pool of light over a comfortable stuffed armchair. A messy coffee table sat in front of the gas heater. Tall bookshelves stood to each side of the mantelpiece, stacked two deep. More books littered every surface. They were even stacked on the floor in wavering waist-high towers.

I had the feeling that Walenski had stopped trying some time ago and had just been going through the motions ever since.

There was only the one big chair and, with the papers and mug on the coffee table, it was obvious Walenski had been occupying it. The old guy pointed through a doorway to the kitchen. 'Bring some chairs.'

Monty snagged two before I could get one for myself. He knew I'd hate it and was just trying to push my buttons. I waited while Monty positioned the two chairs on the far side of the coffee table which stood in front of the heater. This was going full blast and the room was so hot, it was almost stifling. Again, a wave of claustrophobia swept over me. Nausea roiled in my belly. My heart raced and I felt the first rush of a panic attack. Had to get a grip.

I sat down clasping sweaty palms over one knee and looked to Monty but he'd wandered off exploring. Typical. I smiled and felt my heart rate begin to return to normal.

Walenski shuffled over to the armchair. 'I've been sorting through it for you.'

I waited, figuring I'd work out what he was talking about soon enough. Besides, I needed to do my meditation breathing.

The old guy lowered himself into the chair with painful care and began reading. I glanced at Monty who had prowled across the room. He grinned then poked his nose into the little kitchen. I heard him opening and closing cupboard doors. Luckily, Walenski was oblivious. Monty caught my eye as he returned to the living room, giving me a little half nod which I took to mean the place was lived-in. Then he opened the door to a bedroom. No rules for the Montys of this world. From the glimpse I caught, the bedroom was as cluttered and fussy as the lounge room with lots of knick-knacks and books.

Walenski kept reading. If it was Joseph Walenski. How had Arthur found him?

'Mr Walenski, I was-'

'It's waited this long, you can wait another five minutes,' he told me, then went back to reading. He looked weary, but he looked like a man who had wrestled with his demons and beaten them.

Monty winked at me and kept moving, this time over to the window that looked down into the street. He ran his finger over the sill and lifted it to show me the layer of dust. It showed up as a pale line on his dark skin. Either this was the actor's own home or this was the real Joseph Walenski's home.

I rolled my eyes and noticed the ceiling. It was pressed metal. Everything in this flat had seen better days, including the old guy.

Before Genevieve's murder, Walenski had lived on an invalid's pension, courtesy of a car accident that killed his parents and injured him when he was in his early teens, but after Genevieve's death his bank account had not been touched. I'd seriously considered that Walenski might be dead. Yet here he was. Supposedly.

I studied the old guy as he read the pages. If this was him, the missing witness had not aged well. The real Joseph Walenski would have been 53, yet this guy looked nearer to 70.

I cleared my throat. 'So how did Arthur find you?'

'Nearly finished.' He held up his hand and shuffled about 20 pages into order. There was a much larger pile of faded typewritten pages covered in scribbled notes. A manuscript. And, from the look of it, he was giving us roughly the first chapter.

Satisfied that the pages were straight, Walenski sat there for a couple of heartbeats staring into the blue flames of the gas heater.

Going on gut instinct, I was inclined to believe that this was Joseph Walenski, the man who had not come forward to save his best friend. But why? I couldn't keep quiet any longer. I shifted on my seat. 'I have some questions, Mr Walenski.'

Monty returned to stand behind my chair. I felt him as a familiar, if challenging, presence at my back.

Walenski looked across at us, his faded blue eyes glistening with tears. He blinked and the tears rolled unchecked down his face.

'I let him down. O'Toole didn't kill Genevieve.'

Sympathy wrenched at my gut, but it didn't stop my questions. 'Then why didn't you confirm Pete O'Toole's alibi?'

A grimace of pain twisted Walenski's features. 'You think you know yourself but you don't, not until you're tested. I failed. I dithered for a week. Truth is, I was a gutless coward. Maybe I would have come forward, but then O'Toole killed himself and there was no point. Guess I'll never know if I would have gone to the police.'

Angrily, he slid a large rubber band around the pages. It snapped, spinning away. He swore softly, his fingers trembling as he shoved the manuscript into a faded manila envelope. He stood and held it out to me. 'Go on, take it. I'm not going to hide anymore. When you finish it you'll understand why I let O'Toole down, and why he killed himself.'

I came to my feet and took the envelope, pulling the manuscript halfway out. It was called Unimportant Murders and headed Chapter One. The feel of the paper and the look of the faded typewriter print told me that this was an old manuscript.

'You wrote this to exonerate O'Toole? You wrote a book?'

'I'm a writer. I've been published in top-paying markets!' He bristled, then added, 'of course that was 25 years ago, but the only reason I haven't been published since is because I haven't submitted.'

'Okay, okay.' I caught Monty's secret smile. Creative people can be so defensive. 'But why write a book? You could have done an interview to exonerate O'Toole.'

He shook his head. 'People can twist your words. I had to tell O'Toole's story so the public got the whole picture. You don't know what it was like back then. When he killed himself everyone saw it as an admission of guilt. But I knew better. I knew the real O'Toole. He wasn't what the police made him out to be. True, he didn't have much schooling and he'd had a rough start in life, got in trouble with the law in his teens, got his first girlfriend pregnant. But he'd married her and tried to do the right thing. He wasn't stupid. He'd taught himself to paint.

'And he cared about the kids on the Street. The injustice of it really got to him. He would talk for hours about things that had happened while he was driving the taxi. After a while I began taping him. He didn't mind. In fact, he got a real buzz when I sold a couple of stories based on stuff he'd told me. I had a ringside seat to his life.

'More than that, in the last week before Genevieve's murder I was one of the players. After he killed himself, the book just poured out of me. I was going to send it to a publisher. I dreamed of it clearing O'Toole and being a bestseller.' He paused, then didn't go on.

'So what happened?' I gestured to the faded pages on the coffee table. 'Why didn't you submit your book?'

All the fight went out of him. 'I had my reasons. Good reasons. You'll see when you read it.'

I glanced down. I was tempted to scoop up the rest of the book and run. 'Why can't I have the rest of it?'

'It's not ready. I did the first draft, but when I went back to tidy it up I realised I couldn't send it out.'

'Why not?'

'You'll understand when you've read it.'

I hated it when people did that.

'If it wasn't O'Toole, who did kill Genevieve?' I asked, cutting to the chase.

He cast me a dry look. Walenski was no fool. 'I can make an educated guess and I know why.'

'Then who is your best guess? And why?'

He shook his head. 'I want you to read it as it unfolds, see if you agree with me.' He hesitated, a self-conscious grin lighting his face and suddenly the years slipped away from him and he was charming. 'I want you to make it into a movie.'

I bit my tongue. Spare me from writers who think their book will make a top-grossing movie.

I must have given myself away because Walenski bristled. 'You're not the only ones who'd be interested in this book. I know if I took it to a major publisher they'd jump at it.'

'Then why don't you?' Monty countered.

'I want creative control,' Walenski snapped, then took a deep breath glancing at each of us. 'And, from the way Arthur talked about you, I thought you'd understand.'

Yeah. I understood. Monty and I exchanged looks.

Walenski stiffened. 'We'll do this my way, or not at all. It's waited 25 years. It can wait a few more days while I tidy up the book. Then I'll start calling the major publishers-'

'Okay, okay.' If he did that my doco would be old news. They'd rush something like this into print, arrange author interviews, the works. Like I'd told Arthur, Genevieve's murder was still topical. 'Okay we'll do it your way. There's just one thing I don't get. Why come out of the closet after 25 years? Were you protecting someone who's dead now?'

He smiled briefly. 'Something like that.'

Walenski held all the cards and I knew it. I'd have to do it his way or not at all.

Even if I convinced the surviving band members to talk, now that I knew about the book, I wanted Walenski's insight to compare with what they said. It sounded like the band had something to hide and, since his agenda was to exonerate O'Toole, he wouldn't be glossing over the band's part in Genevieve's murder.

'Still got the tapes?' Monty asked. It was off tangent, but a good point.

Walenski nudged an ancient cassette player with his shoe, pushing it out from under the coffee table. I shivered, imagining him listening to the tapes before we arrived, communing with the dead. I seemed to hear the whisper of long gone conversation and felt the walls press in on me. Breathe, Antonia, breathe.

'Can we have a copy of the tapes?' Monty asked.

'No,' Walenski snapped. I glanced at Monty.

'Only a copy,' he said. 'To authenticate your book.'

Walenski sighed. 'The tapes are private; O'Toole rambles. He gets maudlin, rages against his ex-wife and rants about the drugs and prostitution on the Street. He said things to me he would not have said to anyone else. You have to understand. He was close to a nervous breakdown when I first met him. His wife had dumped him for another man and it was eating away at him. He adored his daughter and she, well, she loved him but she was trying to make a life for herself. When he first moved in upstairs, he was in such a bad way he couldn't sleep, that was why he drove the taxi at nights, to stop from going crazy.' He glanced at a battered briefcase on the floor next to his chair. 'The tapes are private.'

'Hang on,' I muttered as something clicked. The boarding house where Walenski and O'Toole had lived burned down several hours before the murder. 'You can't have the original tapes. According to the police all of O'Toole's personal effects were destroyed in the fire. Your stuff must have gone up in flames too.'

'That's what everyone thought. But the very afternoon the flats burnt down O'Toole insisted we pack an overnight bag and go stay somewhere else. I took the tapes because I happened to be working on a story at the time.'

Seemed plausible, but why had O'Toole insisted they move out?

Walenski gestured to the manuscript. 'O'Toole could never have hurt Genevieve. He loved her, we all did,' Walenski's chin trembled. After a moment he went on. 'When he committed suicide it wasn't because he'd killed her, it was because he hadn't saved her!'

Monty snorted softly.

Walenski glared at him, an old man's ineffectual anger.

'Okay. You've got me hooked,' I said quickly. 'According to you, this book will tell us what happened.'

'Yes.' He nodded. 'In the last week before she died.'

'How do we know you're telling the truth?' Monty countered.

Walenski pulled himself upright, furious and frail. 'I've laid myself bare in this book. What more do you people want, a pound of flesh?' The anger drained from him and he cast Monty a weary look. 'Read it. Then ask yourself if I'm hiding anything. Now, get out!'

Back at One-Eight-One, I unlocked the sliding door and noticed the cat had eaten his food. Monty put a pizza on the kitchen table and flipped the lid open, while I poured the wine. The pizza smelt good. My stomach rumbled as Monty passed me a plate and cutlery. For once he didn't tease me about eating pizza with a knife and fork.

I grinned, riding a surge of excitement as I slid the manuscript out. I was holding something that had never come to light. Except for Walenski, no one else knew what we were going to discover.

'Do you suppose Arthur's read this?' I asked.

'Walenski said no one had. But Arthur obviously meant him to give it to us.'

'So he must think there's something in it that we should know. It's his way of settling Genevieve's ghost. He said he owed her.' My palm itched and I was suddenly very aware of the dark night outside. I got up, crossing to the sliding doors to adjust the vertical blinds.

Monty gave me a questioning look.

'There was a gap. Someone could see in.'

He grinned. 'The back fence is as tall as me.'

'They could still climb the fence.'

'Paranoia reigns supreme.'

I stiffened. I was not loopy. I was nothing like my mother.

Monty studied me.

Either I had revealed too much, or Monty saw too much.

Hurriedly, I crossed to the table and sat down, scanning the front page of the manuscript. 'Walenski's started the book on Monday afternoon. Genevieve was killed the following Sunday. Six days to set up her murder. He doesn't believe in mucking around.' I looked up, meeting Monty's eyes. 'Ready?'

'Just try and stop me.'