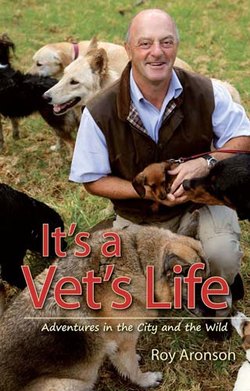

Читать книгу It’s a Vet’s Life - Roy Aronson - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Fate almost sealed

ОглавлениеWhen we’re young, enthusiastic and passionate, sometimes we do crazy things. But perhaps this is not such a bad thing. I am a determined person and once I get the bit between my teeth, I don’t like to give up. This story happened a few years before I entered Veterinary School and while I was in the South African Navy. I was young, reckless and not as cautious as I am today. It set me on a path that I would otherwise not have trod.

I graduated from the University of Cape Town in 1976 with my first degree, a BSc with majors in Microbiology and Biochemistry, and successfully applied to join the South African Navy at its base in Simon’s Town, a picturesque fishing village on the stormy False Bay coast. I was seconded to a laboratory that did quality control work in the engineering field. I was given various tasks to do but I was also allowed to choose one or two ‘special interest’ projects to keep me occupied if I had any spare time. I chose to do some investigations into anti-fouling paints that are used to coat ships to prevent barnacles from attaching to the hulls. If not for them, literally tons of barnacles would add massive drag to the ships. This would, of course, slow them down and dramatically increase fuel consumption.

My project involved coating small pieces of steel about fifteen centimetres square with the various anti-fouling paints on offer, hanging these pieces of steel at various depths from a raft and then measuring the number of barnacles that attached themselves. In this way I was able to assess the effectiveness of the paints and compare them so that the navy could choose the best one.

I was given the use a small rowing boat to access a raft moored on one side of the harbour out of the way of passing vessels. My raft was moored next to a number of floating pontoons where seals would sun themselves. There I diligently set up my experiment and hung numerous plates from ropes going down into the blue depths of the Simon’s Town harbour. My experiment was designed to run for a year, through all four seasons.

I spent many happy hours rowing out to my little raft in the harbour and measuring the number of barnacles that had attached themselves to my plates that were coated with a substance designed to prevent just that. It never ceased to fascinate me how those clean, painted plates attracted and accumulated life in abundance. First the plate became slightly roughened as microscopic sea creatures attached themselves to it. Then, over a period of a few days, the rough patches started to take the form of miniature little barnacles that you could see with the naked eye. These tiny barnacles grew until eventually, after nearly a year, they had grown to sea creatures coated in a hard shell a number of centimetres in height and diameter. During the summer months I’d row out with my shirt off and when it was really hot, I’d dive into the water in my shorts and spend some time in the sun drying off before I rowed back to the shore and my lab. Clearly this was a busy time for me. I was hard at work having a good time! During winter it was a lot less fun.

Towards the end of the first summer I noticed that a young female seal had beached herself on a nearby pontoon. She had a distinctive marking, almost like a dark shadow, around her neck. In passing I wondered if there was a species of seal known as a collared seal. I knew there were collared birds and lesser collared birds; perhaps there was a collared seal as well. I did not pay too much attention to her but made a mental note to be cautious because although these sleek and engaging creatures look friendly, they can in fact be aggressive if they feel threatened and can inflict a very nasty bite if you get too close to them. I decided not to swim if she was in the vicinity.

It was three days later when I next went out to my raft. I noticed that the same young female seal was still on the pontoon. She seemed to me to be thinner than before and the dark shadow around her neck had now taken on a reddish tinge, almost as though the colour had run in a dyed garment. Something was not right. It seemed strange that she was still there in the same position. The discolouration around her neck now looked sinister to me and I decided to row back to the lab to fetch a pair of binoculars so that I could get a better look.

I arrived back at the raft about half an hour later and used the binoculars to observe the seal. To my horror, the so-called shadow around her neck was actually fishing nylon that had tangled and formed a noose that was now extremely tight and cutting into her flesh. The reddish tinge that I’d seen was in fact blood seeping from the wound caused by the ever-tightening noose. What was I to do? I only knew that I had to help. I got back into my rowing boat and rowed a bit closer to the pontoon where she was sitting. She must have felt very threatened because she started to bark and vocalise fiercely. Her distress and dare I say anger was very obvious. Well, with the cacophony of sound coming from a mouth filled with large yellow fangs bigger than those of a German Shepherd dog, I too felt threatened. As the gap between my boat and the pontoon closed, she panicked and dived into the sea, her ultimate escape. Clearly this approach was not going to work.

I now had a problem that I very much wanted to solve. But back in ’76 there were few resources to turn to. Today I would have ‘Googled’ the problem on the Internet or asked the aquarium for help but these avenues didn’t exist then. I turned to the Fishing Industries Research Institute. A member of their staff was an expert in marine mammals and, convinced that this was a fairly common problem, I hoped that he would be able to help me solve it. I called him and our discussion did bear some fruit, although in an oblique way. He informed me that there were no quick-acting drugs available to inject or dart seals. Once darted, the seal would take fright, swim away and be long gone by the time the drugs took effect. Now deep underwater and impossible to find, the seal would slip into dreamland and drown. So, to my surprise, he explained that there was no protocol for this problem. Each time something like this came their way it was dealt with on an ad hoc basis. He felt that the only way to save the seal was to actually capture her in a net. Once netted, she could be safely immobilised with a sedative without the risk of drowning. Alternatively, if the seal was small enough, he recommended muzzling her and then wrestling her into a position where the noose could be removed. Given the size of her teeth, the sedative option seemed more attractive to me at the time.

Armed with this plan, I contacted a local vet and explained the problem to him. He very kindly volunteered his help. This was progress indeed. I obtained a large net from the navy store and I made a long pole with a big loop of stiff wire at the end. I sewed the net into a bag large enough to capture the seal and attached it to the wire loop. Once all my equipment was ready, I contacted the vet. He drove out to the dockyard where we boarded the rowing boat and confidently set off to capture our seal. How naïve we were.

Before we could get close enough to net the seal, she sounded her alarm clarion by barking frantically, after which she dived into the water and swam off without a backward glance. The vet kindly offered to wait for a while and so we bobbed up and down in the water just off the pontoon for half an hour. After this time it was clear that the seal was not coming back so we had to abandon the plan and row back to shore. I was now on my own. While pondering the problem, I looked through the binoculars to try and get a view of the pontoon and blow me down but our seal was back on the pontoon sunning herself. Once we had departed she must have felt safe enough to return.

The next few weeks were a stalemate. Every time I approached the pontoon, she would dive into the water and swim away, not letting me come even remotely close to her. The only small consolation was that she returned to the pontoon time and time again. She must have felt safe there because out in the open ocean, debilitated as she was, she was a sitting target for any number of predators, not least of which the Great White shark. False Bay has a large population of seals and a large population of Great Whites that prey on them, and this injured seal would make a quick and easy snack for a cruising Great White.

She was now even thinner. I noticed that her forays into the sea were getting shorter and the time she spent lying on the pontoon was getting longer. I wondered if she was eating. Seals are hunters and need to be fully agile and healthy in order to hunt successfully. This seal was getting weaker and thinner, and I was sure that her success as a hunter was being compromised.

I decided to try and feed her so I went to the local fish shop in Simon’s Town to buy some fresh fish. I got the fishmonger to cut the fish into what I considered to be bite-sized snacks for a seal and then rowed out as close to the pontoon as I could get without startling her. By now she was getting used to me and I was learning about her boundaries. I knew how close I could get before she would jump off and swim away and it seemed to me that I was able to get closer and closer each day. I wondered if this was because she was getting used to me or whether it was because she was simply getting weaker by the day.

I rowed up to a distance that did not frighten her and threw a piece of fish on to the pontoon about a metre away from her. To my disappointment she did not make any effort to try and eat the piece of fish. I threw another piece closer to her this time but still she ignored it. I decided to row a bit closer and throw fish into the water, hoping that she would jump off the pontoon and feed from the fish pieces in the water. But this did not work either. I now realised that despite my best efforts to help her, there was a real possibility that the seal would die.

I sat in the rowing boat, bobbing up and down a few metres from the pontoon feeling frustrated and dejected. Was this beautiful sea mammal going to die? Was there no way to get close enough to her to sever the nylon that had embedded itself around her neck?

During this time I had asked a number of people for help and each time someone would come up with a new suggestion as to how to capture her or immobilise her. But no matter who tried or what was tried, we got the same result. When she felt threatened by human proximity she would jump in to the safety of the water and swim off. She only returned when we had retreated a safe distance.

The hours became days and the days became weeks and she became weaker and weaker. After a month of trying everything I could think of, she was so weak that I was able to sit on the pontoon a metre away from her without her jumping in to the sea to escape. She stayed tantalisingly just out of reach so that even though I was able to sit really close to her, it was just not close enough to cut the nylon. She was dying and I felt totally useless.

At this point fate took an unexpected and very welcome hand in the matter. The expert I had called at the Fishing Industries Research Institute called me to ask how things were going. I told him my sorry tale and said that unless something drastic happened, she would die within a few days. He offered to come out the next day to see what we could do together. I thanked him gratefully for what I considered to be an eleventh hour reprieve.

The next morning I went to work with considerably raised spirits. My contact arrived with a bag filled with equipment, including a special throw net that had a leather hood. He told me that since the seal was so weak, we could try to throw the hooded net over the seal, immobilise her mouth and prevent her from diving into the sea. He also had a pair of scissors with long handles and a pair of heavy leather gloves. Equipped with this bag of tricks and new found hope, we rowed out to the pontoon. The seal was lying there and was a depressing sight. Her eyes were dull and her fur lacklustre. I was sure that she was near death. We were able to get on to the pontoon without her moving away and I think that at this point she was just too weak to offer any meaningful resistance. I doubt that she would have been able to swim had she had the strength to jump off the pontoon.

My friend donned the heavy leather gloves and with a casual but experienced flick of his wrist, he threw the net over the recumbent seal. He quickly grabbed the ends of the net in case she jumped off the pontoon and maneuvered the hood over her head. He then managed to sit astride the seal, something I have no doubt he would have been unable to do if she had been healthy and up to full strength. In the meantime I had grabbed the long-handled scissors and quickly went to work cutting through the heavy line round her neck. At long last the noose of death was off but I wondered if it was too late. Now all we could do was inject her with antibiotics and an anti-inflammatory and hope for the best.

Nature is a wonderful thing. Given the opportunity, once the underlying cause has been removed, most animals will heal themselves even in such an advanced state of debility as the seal was in.

I watched her with wonder as the next two weeks passed. The first thing I noticed was that even by the next day, a scant twenty-four hours later, she started swimming a bit more and lying on the pontoon a bit less. I hoped that she was strong enough to hunt because by the time we actually managed to remove the noose she was just skin and bone. Within another day or two her coat started to regain some of its beautiful lustre. After a week she was swimming vigorously and spending less and less time on the pontoon. I had no doubt that she was able to hunt because she actually started putting on weight at an amazing rate. From day to day I could see the difference. The cut around her neck was healing and the seeping had stopped. The dark ring of fur was still there and I wondered if the fur might not be permanently stained. Blood is a strong attractant to sharks and her instincts must have made her aware of this because she never really strayed outside the harbour precincts during her recovery.

The last time I saw her on the pontoon was two weeks after we had removed the noose. She was once again sleek and, dare I say, almost fat. Her wound had healed completely and there was no blood seepage but the dark ring was still there. When I came too close she barked loudly and dived into the water.

And then one day she just was not there anymore. I guessed that she had recovered fully and was now able to resume her life as a seal in the open ocean.

A few months later while I was working on my raft and measuring barnacle growth, I looked up and caught a glimpse of a sleek and fat seal, about the same size as the one I had helped. The seal jumped onto the pontoon for a few seconds and then dived off and swam away. But not before I noticed a black ring of fur around her neck.

My life has been shaped and continues to be shaped by all the little experiences that have accumulated over my lifetime. I know for certain though, that this was a pivotal experience for me. It was the catalyst that made me want to become a vet. I had a good degree and I was comfortable cruising along in the navy, but then along came a seal that I struggled desperately to help. I knew from then on that I wanted to spend the rest of my life working with animals. I am grateful to the seal for coming into my life and allowing me to help her, and I am grateful that she helped me.