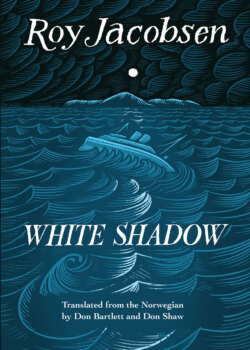

Читать книгу White Shadow - Roy Jacobsen - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

6

ОглавлениеIngrid knelt down and tugged at him. He didn’t react. Through a rip in his trouser leg, at the top of his right thigh, she saw a deep wound with edges that had swollen to form thick, blue lips. She pressed her fingers against them, saw living blood and heard a distant groan. One of his hands looked as if it had been burned in a fire, but most of the fingers were intact, the nails on the other hand were missing, it too was black.

Ingrid wrung a few drops out of the uniform and tasted them, it wasn’t salt water, so there had to be a boat somewhere around the island, moored presumably in the only place she hadn’t looked, near the ruins at Karvika, she was afraid of the ruins at Karvika, she always had been.

She managed to raise him into a sitting position, went down on her haunches and locked her hands around his chest, dis-covered how surprisingly light he was and dragged him over to the barn door, unbolted it and lugged him through the garden and into the kitchen, manoeuvred him up onto the bench, and covered him with blankets.

She grabbed the ladle in the bucket, propped him up and moistened his cracked lips. He writhed and groaned. She shoved a cushion under his head and fetched a funnel, stuck it down his throat until he retched and forced open his singed eyelids and tried to resist with his hands.

She held the ladle in front of his wild eyes.

He nodded, drank a few drops, coughed and raised his mangled hands as if to study them, and display them to her, or to God, as soot-blackened tears streamed from his scorched eye-sockets down his skeletal face, finding nowhere in his smooth, young features to stop them, making him look as if he had never been human, nor ever would be.

She grasped the hand missing only fingernails, sat holding it, staring into space, when she suddenly felt an imploring tremor, as if he were preparing to die. She began to shake the limp body, shouted no, no, grabbed the ladle and forced more water down him, causing more fits of retching, which eventually abated, reducing him to a whimpering infant, and the stench that permeated the warm kitchen was unbearable.

She got to her feet, went into the larder and stopped in front of the rows of shelves stacked with preserves and canned food. She grabbed a jar of redcurrant jelly and spooned the contents into a cup, mixed it with warm water, breathing through her mouth, and began to force a thin, red liquid down him. He coughed and spat and had to gulp to avoid choking, managed a few greedy gulps, brought them up again, swallowed a few small spoonfuls, she counted them, and he kept them down, until he passed out.

Ingrid placed the cup on the table, wiped her face on her jumper, heard two sobs, which were her own, and declared in a loud voice to the walls that this could not be true, before once again making sure that he was breathing, whereafter she went out into the driving snow and stared up into the darkness.

Only to realise that there was no way out of this.

She walked down to the landing stage and put out the boat, rowed around the northern promontory, where she had the wind in her face and kept beneath the jutting rock face, headed south through the foaming breakers to the fleet of nets, where the cries of the birds above Moltholmen were carried to her on the wind.

Using the last reserves of her strength she crossed the sound and jumped ashore, the boat left pitching against the rocks. She bound the mooring rope around her wrist, grabbed an oar and thrashed out at the swarm of screeching birds. The dead man came into view with a bluish-black hole for a face and his belly agape like a gutted cod through to the spine, his hands gnawed-off stumps of bone and his feet resembling charred wood. She slung the oar back into the boat, managed to lift him clear of the anchor peg and down into the seaweed, but not onto the boat. She wrapped the mooring rope around his thigh, leaped aboard and towed him along beneath clouds of birds making wilder and wilder dives into the wake. But now she had the wind at her back and sped along until, sheltered by the quay house, she was able to untie the mooring rope at the bow, step onto the quay and attach it to the hook on the windlass and hoist the man free of the water; he hung upside down like a man on the gallows.

The white-headed eagle stood on the quay beside her like a tame animal, she kicked out, it waddled away, she kicked again, screamed and lost her grip of the winch, caught it again and locked it into position, grabbed a wooden pole and lashed out wildly at the enormous bird, which lazily waddled to one side. She ran back to the windlass and lifted the man the last few metres up onto the stone quay, opened the doors of the quay house and dragged him inside, whereupon she discovered that one of his trouser legs was empty.

She closed the doors, shrieked at the swarm of cackling birds that had settled on the quay and the windlass and the roof, walked down to the boat and rowed back to the shed. She found herself crying and realised she had been doing so ever since she left the house.

She wiped her face on her drenched jumper, walked up the hill and again into the stench that filled her kitchen like intense cooking fumes and saw that the cup of redcurrant jelly was empty.

She tore off her jumper, tied a headscarf around her mouth, removed the blankets and began to undress him.

Beneath the uniform were the same brown rags, wood-shavings and an indefinable grey mass resembling sodden paper. She picked it all off him like dead skin from a sunburnt back, cloth, skin, soot, mould, and stuffed it into the stove, almost smothering the flames. She put in more wood and the temperature rose as he screamed in a voice that was not human.

Then she had to throw up before she could continue.

When he lay naked before her, black, pink, yellow and bluish-green, like a charred map of the world, she poured lukewarm water into a bowl and set about washing those parts of him that were unscathed; he moaned and struck out at her. She had to sit on him, and also removed something from him she could not identify, was it underwear or burned skin? He passed out again and lay motionless like a corpse, but still breathing.

She carried on until she was finished, filled the stove with the rest of the rags, went upstairs to the South Chamber and came back with an eiderdown and a new rug, slipped the rug under him and laid the eiderdown over him, opened all the windows and doors, filled all the saucepans she had with water and put them on to boil. She fired up the stove, hotter than on any baking day, while reassuring herself time and again that his slumber was not the sleep of death.

In a frenzy she tore off her own clothing, and burned that too, washed her body, put on some dry clothes, and the stench was no less abominable.

She pulled the eiderdown off him and began to wash him again, rubbed the thin skin, which in places was as smooth and white as a cod’s belly, fetched some talcum powder and burn ointment, and a needle and thread, heated the needle over a candle and began to sew the gash in his thigh. Tremors spread through his frail body, but he still had a pulse, regular, and kept groaning until she put down the needle and bandaged the wound.

She shut the windows, went into the sitting room and looked at herself in the mirror above the chest of drawers, smacked her stiff, unrecognisable lips, then went back and sat down, alternately looking at him and down at her own hands, they were swollen and puffy due to the water and frost, but they were not shaking, and when she opened her eyes again she was lying curled up on the floor next to a stove that had gone cold in a kitchen without light, and outside there was silence.

~

She rolled over onto her back and lay listening to the calm, regular breathing on the bench, the night beyond the window panes was black.

She got to her feet like a stranger to herself, pulled off the eiderdown and stood gazing at him, covered him again, lit the stove and dressed to go out and look for the boat they must have arrived in and found it where she knew it would be, on a low-lying spit of land at Karvika, an oval, dirty white craft made of planks and metal cylinders, more a raft than a boat, probably visible through binoculars from the main island, in daylight and clear weather at any rate. Now it was dark, but the stars were out, so she couldn’t burn it, nor would she be able to drag it over the crag and out of sight either.

She sat down.

It was quiet. No birds. She got up and spotted some drain plugs in the tanks, managed to loosen them and push the boat back into the sea and loaded it with rocks, launched it with her feet and watched it fill with water and sink like a white shadow. Now only the lustreless stars were reflected on the surface, she had forgotten her mittens and couldn’t move her fingers.

Back at the house she took off all her clothes again and inspected every inch of her body, as if looking for lice, then scrubbed herself until her skin was red and sore, until she was both hot and cold; she went into the sitting room and stared in the mirror, her face was dry and her body wet.

She dried her body and put on some potatoes and fish, overcooked them and mashed everything together, mixed in some liver and began to feed him.

He fell asleep.

She laid a hand on his wound.

He opened his skinless eyelids and peered at her with pupils like jellyfish in a black sea. She showed him the spoon, he nodded and opened his mouth, she fed him and he sucked and managed to swallow. She gave him another spoonful, and another, and warm redcurrant jelly, he coughed and drank, was given more and passed out in mid-mouthful. She wiped his chin, put a hand first on his forehead, then on his neck, to feel for a temperature and a pulse, and kept it there for so long that it seemed like a caress, then withdrew it and stared at it and stroked his chin twice more because it was impossible not to. Then she ate the rest of the food and went upstairs and fell asleep, fully dressed.