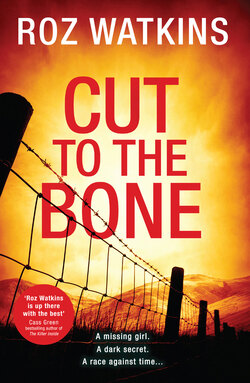

Читать книгу Cut to the Bone - Roz Watkins - Страница 15

6

ОглавлениеJai and I pulled onto the road out of Buxton. The sun was a vivid orange, and smoke from the wildfire was drifting up from the hills, leaving a hint of bitterness in the air.

‘Did you get any more info on him?’ Jai asked.

‘Tony Nightingale? Pig farmer and all-round country gent, from a long line of similar. Rolling around in cash, by all accounts – and owns a lot of the land around here. Violet turned up at his house around eight, saying she was related to him. Could be a good lead. Maybe it’s all a bit Thomas Hardy and he’s her biological father?’

We drove through Winnats Pass, a spectacular, steep-sided limestone valley with cliffs on all sides, formed from a long-ago collapsed cave system. It had once been the main route between Sheffield and Manchester, famous for its bad weather and bandits. We went another mile or so in silence, and then ground to a halt in the traffic of Castleton. Tiredness was catching up with me, and I wished again that I hadn’t invited Hannah over.

We chugged onwards, leaving Castleton and heading through the Hope Valley and up through Bamford, before reaching the outskirts of Gritton.

A red-brick farmhouse sat by the road, a tree-lined lane curling round behind it. A fence corralled a small garden, and an old path overgrown with weeds led to what looked like the original front door. A sign proclaimed Mulberry Farm – Rare Breed Pork. It was a decent-sized house, set apart from the neighbours, but wasn’t that grand for a supposed country gent.

I drove round to a yard at the rear, passing a field inhabited by pigs wallowing in mud. I regarded them with envy.

‘Nice,’ Jai said. ‘Shame they’re going to end up on someone’s breakfast plate.’

‘You could always go veggie,’ I said, ‘if you’re feeling bad.’

‘But bacon tastes so good …’

I remembered what Violet apparently said. That using the taste of bacon as an excuse for eating it was like saying it was okay to rape someone if you enjoyed it. Definitely an odd thing for our bikini-wearing sausage-sizzler to come out with.

We knocked on a solid, newly-painted door at the back of the house. To the side was a rose garden, overgrown and knotty, with long grasses growing between thorned stems.

The door was opened by a man with the corduroyed, bespectacled look of a university professor. He didn’t fit my image of a pig farmer, although I told myself there was no rational reason why a pig farmer should look like a pig. Then I noticed he had a thin covering of light, fair hair, almost like the hair on a pig’s back, and I felt strangely reassured.

We showed the man our ID and he nodded calmly, confirmed he was Tony Nightingale, and ushered us inside. The door led into an unmodernised farmhouse kitchen, complete with Aga, non-fitted wooden units, and pungent, aged black Labrador. We sat at a Formica table while Tony Nightingale made tea. The Labrador lay on its side, only raising an eyebrow in greeting.

‘Violet Armstrong came here last night?’ I said.

‘Yes.’ Tony placed a teapot, cups, and a milk jug in front of us, and lowered himself into a chair. ‘I’m sorry. It’s all such a shock. She said some rather strange things.’

‘What did she say?’ I asked.

Jai fished out a notebook and pen.

‘I didn’t know who she was. I don’t know about blogging and videos or whatever it is she does. But she told me not to tell anyone she’d come because she didn’t want any publicity. And then …’ He put his cup down with a trembling hand. ‘Sorry. She said she was my granddaughter. She said her mother was dead and she wanted to find her relatives. And to find out who her father was.’

‘Did you get to the bottom of it?’

He folded his arms. ‘She’d been told that her mother was called Rebecca Smith. My daughter is Rebecca and she took my sister’s name, Smith, when she went to live with her. But my daughter, Bex, isn’t dead.’

‘Did your daughter have a baby?’

Tony looked out into the garden. The evening sun was glistening on a climbing rose. A flash of anguish passed across his face. ‘If she did, she never told me.’

‘How old would Bex have been eighteen years ago?’

‘Only sixteen.’

‘Was she living with you at that time?’

Tony looked down. ‘She lived with her aunt. My sister, Janet.’

‘Oh?’

‘Yes, I’m afraid so. It was … hard. My other daughter, Kirsty, lived with me.’

‘What was the reason for Rebecca – Bex – living with her aunt and not with you?’

Tony jumped up. ‘I forgot the biscuits.’ He opened a wall-mounted cupboard and fished out a biscuit tin which he placed on the table with a flourish. ‘Only Rich Tea, I’m afraid.’

‘Thanks.’ Jai was straight in there, as was the aged Labrador, who’d done a Lazarus-like manoeuvre and was now sitting staring dolefully at Jai while he rummaged in the tin.

‘Ignore him,’ Tony said. ‘Burglars could maraud through the house unimpeded as far as he’s concerned, as long as they didn’t open any food containers.’

‘Aw,’ Jai said. ‘He’s hard to resist.’

I smiled. He was indeed hard to resist. I blamed those hypnotic eyes. ‘So, Bex went to live with your sister?’ I said.

‘Yes. My wife, Nina, and I split up. Nina was from the Ukraine and she returned there when Bex was only three. I found it difficult to cope with two children.’

‘Nina left the children with you?’

He nodded. ‘I suppose she thought they’d have a better life here. I was terribly upset with her at the time, but now I think she was suffering from depression. I should have given her more support.’

I spoke gently. ‘If Bex didn’t live with you, is there a chance she could have had a baby eighteen years ago?’

‘She was only sixteen. And Violet was sure her mother was dead. I tried to call Bex, but she hasn’t got back to me. Then I phoned Kirsty, to see if she knew anything about it, but she didn’t. I can’t ask my sister – she died of breast cancer two years ago.’

‘I’m sorry about that. We will need to speak to Bex. You say she took your sister’s surname when she went to live with her?’

‘Yes. Smith. For all intents and purposes, my sister adopted her. It was much easier with schools and things if she took her name.’

‘Okay. We’ll take her contact details from you.’

‘Oh Lord.’

‘Before we go, we’d like to clarify – the missing girl, Violet, was born in May 2000. When did you last see your daughter before and after that date?’

A look of shame crossed his face. ‘She stayed here for a month the summer before that. I haven’t seen her since 1999.’

‘Is there a reason you haven’t seen her?’

He swallowed. ‘She doesn’t like coming to Gritton, and it’s hard for me to get away, what with the animals.’

‘Why doesn’t she like coming to Gritton?’

He looked out of the window at the old rose garden. ‘I think she just has a very busy life. She’s a dog trainer.’

I knew all about fathers who didn’t see their daughters, but a ‘busy life’ didn’t explain what was going on here. I was very keen to meet Bex.

‘I love my daughter,’ Tony said. ‘It’s just … shocking the way the years slip by.’ He pointed to a framed photograph on an old dresser. ‘That’s her. That’s my Bex.’

The photo was small and I had to stand and take a step closer to see it clearly. A slim, dark-haired girl of about sixteen stood next to a huge, spotty pig, smiling with exactly the same radiance as Violet.

‘Do you think this Violet might be my granddaughter?’ Tony said.

Looking at the photograph, he must have suspected as much. ‘We’re investigating that possibility.’

Tony nodded slowly. ‘Right.’

‘What time did Violet leave your house last night?’ I asked.

‘About nine thirty. She said she had a job at the abattoir. She had white overalls on, so I suppose she planned to go straight there. But she was agitated when she left.’

‘Violet didn’t react well to your conversation?’

‘She was upset. Kept asking me who her father might be. I said I had no idea and she didn’t like that at all. I’m afraid she left here in a terrible state.’