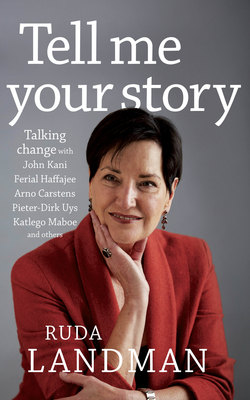

Читать книгу Tell Me Your Story - Ruda Landman - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

John Kani: “Just say the truth”

ОглавлениеJohn Kani was born in New Brighton, Port Elizabeth, in 1943. He has spent a lifetime in the theatre, first as an actor and later as playwright and director. His work has been lauded all over the world. At the time of this interview in November 2016, he was the director of the Market Theatre Laboratory, which he started with Barney Simon in 1989.

Ruda: Did you grow up politically aware, John, or did something happen to push you in that direction?

John: No, my mum and dad were normal people. My dad was a policeman, from the war. My dad was six feet eight inches tall, and two metres wide. That was my image of him when I was young. And he was a very strong man. There were rules at home. Things were right or wrong. Not political or non-political, not illegal or legal, but right or wrong. My mother worked as a maid at the Empilweni TB Hospital, and at the Livingstone Hospital. And there were eleven of us at home – talk about family planning! My dad invested in the children. He used to say, “I am putting my money into you. One of you might work.” But the environment in my township [New Brighton, Port Elizabeth] was heavily politicised. In those days the Eastern Cape was regarded as the powder keg of the struggle. Everything would start there.

So that was our environment: at home, strict religion, Christian; outside, in the [liberation] movement. Those were the two sides of my life. But my life was also ordinary, like other children’s. I completed high school and was ready to go to university, but that did not work out, because my eldest uncle was arrested and got five years on Robben Island. So my father said to me, “Sorry, I can’t send you to university.” I had already enrolled to become an attorney. I was going to be an attorney, oh my God . . .

Ruda: Were you going to Fort Hare?

John: I was going to Fort Hare. And I thought, I’ll become a human rights lawyer; I am going to use this. But at the same time the ANC [African National Congress] was recruiting [trainees for the movement], my list was up and I was ready to go. And then my father came home that night, so drunk. He fell down in the front doorway – there was only one door to get out. I thought he was going to wake up, so I could take him to his room and leave. Quarter past three, I heard the hooter. Papap! I knew it was time to go, but I couldn’t lift my father. I tried pushing out the burglar bars in all the rooms. I was begging him, “Dadda, please go to bed.” My mother was shouting, “Come to bed, Fanie!” Finally I got out, but that was it. I had missed the train.

Ruda: So your father literally, physically, blocked your path.

John: Physically blocked my way. So I didn’t go into exile to train for the ANC. I was so hurt, miserable.

Ruda: How old were you?

John: I was about eighteen, nineteen. I didn’t know what I was going to do next. Then I heard of a drama group called the Serpent Players, who were doing a play called Antigone. They were looking for someone. I was part of the drama group at my high school, in matric. So I went there. And that was the first time I met [playwright] Athol Fugard.

Ruda: Your partnership with him and [actor] Winston Ntshona was the next step, right? Sizwe Banzi is Dead and The Island came out of that.

John: Yes, in 1965 I met the boertjie, with his little beard and smoking a pipe. I thought this cannot be the famous Fugard. This must be a caretaker. Fugard must be inside, looking suave and intelligent.

Ruda: Distinguished.

John: And distinguished. But one of my friends said to me, “John, this is Athol. Athol, this is John.” You don’t know what that meant to a young man who was angry. For the first time I was introduced to a white man on a first-name basis. He didn’t say to me, “John, this is Mr Fugard, Mr Fugard, this is John.” And Athol said, “Sit down.” And thus began this incredible relationship, at a very difficult time. A relationship we couldn’t talk about in the militant township – that we were working with a white person and we had become friends with a white person. Even my younger brother, who was shot in 1985, kept saying to me, “Careful, the word is going around, you are mixing with the enemy.” I said, “You don’t understand; the guy knows what I want to know.”

Ruda: Tell me about the role of protest theatre in those days. You said you did not even have scripts . . . and that it was difficult, and dangerous.

John: We started by doing normal theatre, things like Antigone.

Ruda: The classics.

John: The classics. Coriolanus by Shakespeare, The Bacchae by Euripides, we did Waiting for Godot. But no one came to the theatre. So one day I thought, is it us who are irrelevant, or are we giving people stuff they don’t want?

And then there was a moment . . . One of the members of the Serpent Players, Norman Ntshinga, was arrested, but before his trial, two [other] men were sentenced to fifteen years. One of them took his coat off and gave it to Mabel [Norman’s wife] to take to his wife: “Tell her I have got fifteen years, tell her she must wait for me.” He was about sixty-eight.

So Mabel took the coat back to this lady’s house. She was sixty-five. She said, “Other husbands get life on Robben Island, other husbands get hanged in Pretoria. Mine got fifteen years. I will wait.” Out of that experience we created, in improvisation structure, a play called The Coat. What would happen to the coat?

That was the beginning of a theatre that asked the relevant questions. Theatre that was about the situation, not just in our country but in our own township, and in that house. And this, for me, was the beginning of what then was to be termed protest theatre. We didn’t know it was protest theatre. It’s the journalists who called it protest theatre, and of course the security police, who constantly visited us, called it protest theatre. We liked the term. It meant that the white ones aren’t comfortable with this theatre. So that’s how all the other works grew, right up to Sizwe Banzi and The Island.

Ruda: And those two plays, Sizwe Banzi and The Island,1 took you out of Port Elizabeth and to the world stage. How did you experience that – being in London, being in America, where colour did not determine everything?

John: It was an incredible experience just to stand at Sloane Square in front of the Royal Court Theatre, just to stand in Trafalgar Square. Just to see this is Hyde Park Corner. Just to be met by all the South African people who were in exile and were living in a democratic environment. That is where I learned the word democracy. You could do what you like.

It was kind of strange to see a policeman walk past . . . and you think, “Here is my passbook,” but he is not interested! And seeing the community of London, black and white, Indian, Pakistani, just living together. We were staring at black-and-white couples, we were staring at everything around us. But what was important, what we were all focused on, was the story we were telling in the theatre. All the awards and the recognition really blew our minds. Because we really had a tiny story of a man who’s got a passbook and changed the photograph because he wants to stay in Port Elizabeth, and the story of two men on Robben Island preparing to do a play for the other prisoners. We were amazed at the reaction.

And the people that came out to see the production. Father Trevor Huddleston came to see it. And I remember O. R. Tambo saying, “What you did tonight in this production is what we’ve been trying to do for over thirty years: to explain the situation at home, to explain how the system of apartheid is inhuman. Not whether it is illegal or oppressive, just inhuman.”

We grew as actors very quickly, and we had to deal with watch-what-comes-out-of-your-mouth. I remember Athol Fugard saying, “Just say the truth. The answer you give must be the truth. The situation in South Africa is terrible enough, you don’t have to lie or make it worse. Just say the truth.” And that’s what has guided me throughout my career when I go overseas. When people ask me what’s going on in South Africa, I just tell the truth.

Ruda: And the Tony Award you won in New York? That must have been absolutely unbelievable – two young men from Port Elizabeth in South Africa winning Broadway’s biggest prize.

John: We didn’t know what the Tony Award was. We did not know. Our producers were the ones who were excited, because when we got the nomination bookings went up by 20 per cent that same day.

Ruda: Of course.

John: Of course. So we went to the Winter Garden Theatre [in New York City] and we sat there and we saw all the stars you’d watched all your life, from Hollywood . . . There was Walter Matthau, Meryl Streep, there was Ellen Burstyn, o my God, there’s Jack Lemmon . . . Everyone you’d seen on screen, they were all there. It was a big thing.

We spoke to Fugard in Afrikaans, saying, “God, the Americans take themselves far too seriously.” So I didn’t hear what was going on onstage. And they said, “The nominations for best actor are John Carn-eye, Anthony Hopkins, Rex Harrison for My Fair Lady, Ben Gazzara, Winston Moshonas . . .” I wasn’t listening; it was going on and on and on. Then this guy says, “And the winner is – oh my God, the winners ARE . . .” For the first time in the history of the Tony Awards, they gave the best actor award for two different plays.

So I didn’t know – did I win for Sizwe Banzi is Dead or The Island, or did Winston win for Sizwe Banzi or The Island? – but we won. We went up on the stage and I said to Winston, “What are we going to say? There’s no speech prepared.” And Winston said, “I am just going to say thank you.” I said, “I am also going to say thank you.” We go up, I get my award, I hold it like this and I say, “Thank you.” Winston comes and says, “Thanks.” And that was it.

The New York Times the next morning says: “It was the most powerful political statement made by actors who in their own country, through the evil apartheid system, are not even recognised as human beings, and to find that the world confirms their identity . . .” I said, “No, man, we didn’t have anything to say!” And that got me into trouble when we got back to South Africa. That’s why we were arrested.

Ruda: Tell me about that.

John: We came back from the Tony Awards . . . The season stretched to 1976. We played on Broadway during 1974, 1975, 1976. Then we went to Australia. [Back in South Africa] we’re playing in a small town called Butterworth. Jirre jong, toe sien ek . . . hoekom sien ek ’n polisieman by die exit uitgaan? Another one there, another one there, toe dink ek, o Jirre, dit gaan vandag gebeur.2

I go on with Sizwe Banzi; the Butterworth city hall is packed. Black and white. People are standing. At the end of the performance, as I take the curtain call, security police grab me and pull me off the stage in costume. The other ones grab Winston. The audience, black and white, rush to grab us – this is 1976 – away from the police. The police reach for their guns.

And I see a young man I know. I say, “Four nine two seven four, four nine two seven four.” That was Athol Fugard’s number at home in Port Elizabeth. We’re bundled into the cars, driven to Umtata, and detained for twenty-three days in solitary confinement. The young man realised it must be a Port Elizabeth number. So he called Athol. And while we are being processed in Umtata, charged under section R400 of the Riotous Assemblies Act, promoting hatred through violence, promoting hatred among races, furthering the aims of banned organisations, furthering . . . I am thinking, “We did a play.”

Then the phone rings and this guy says, “Hold it, Lieutenant, hello . . . no . . .” It was Athol phoning: “Are John Kani and Winston Ntshona detained there?” And the guy said, “No, we don’t know what you’re talking about.” But because of that call there were massive demonstrations all over the world: New York, London, Paris, Sydney. People writing to the South African government, even Peter Brook,3 the Fraternity, the Screen Actors Guild. And through that pressure, we were released.

Ruda: The next point that stood out for me in reading your story was the interaction with Sandra Prinsloo on stage. A black man kissing a white woman – well, they kiss each other – and the huge reaction. What was the play?

John: Miss Julie. It’s 1985, right? I was so fed up with protest theatre, I wanted to do something else. And then I got a call from John Slemon at the Baxter Theatre: “Would you like to do Miss Julie by Strindberg?” I said, “Fantastic!” Then I found the script and I read the play. I thought, oops, the relationship between these two people may cause a little bit of uncomfortableness. But it’s not protest theatre really. It’s a play written in 1888. Strindberg is a bloody Swede, he has nothing to do with my country.

Ruda: The play doesn’t say it has to be a black man and a white woman. It just happened like that. It’s not like Desdemona [in Othello].

John: No, it’s not like Desdemona. Miss Julie is upper class. From the nobility.

Ruda: It’s about class differences.

John: Ja, Miss Julie is the nobility. And John is a footman, he’s a servant. So it was unthinkable that a relationship could develop between a man and a woman from these two classes. In fact, in 1888, when the play was performed in Stockholm, it caused the same furore, because it would encourage crossing cultural and class lines.

So toe dink ek, Sandra is so mooi, blonde, blue eyes en mooi gebou, dit gaan bietjie lekker wees.4 Bobby Heaney was the director. And then a journalist from the Sunday Times came to take a picture for pre-publicity. She said to me, “Hold Sandra like this, and just . . . almost kiss.” There was about two centimetres between our lips. We didn’t really kiss.

Jirre, the Sunday Times! BLACK MAN KISSES WHITE WOMAN ON STAGE. Dr [Andries] Treurnicht raised the issue in Parliament: “Kyk as ons nie versigtig is nie, sal die toekoms só lyk.”5 What a prophet!

At the first performance, there was a bit of a tension. Two people walked out. On the second performance, the word had gone out. Jirre, the community of Cape Town, from Langa, from Gugulethu, from all over, came to see the spectacle of a black man, and a militant actor like John Kani, kissing this Sandra, who is a nooientjie van die Afrikanernasie.6 People started walking out.

Ruda: Black people?

John: No, no. Oh, black people wanted more. White people. But . . . a few white people left. The rest stayed. Then the crunch came when they opened at the Market Theatre. Gerard Maclean from The Star phoned me and said, “Tonight there’s going to be some kind of a protest. I don’t know what, it’s just information I am getting.”

So I tell Sandra, “Something is going to happen tonight. If you feel unsafe, look at me and nod, we will both leave the stage.” I made a little joke. I said, “My people don’t mind me kissing you, it’s your people who have a problem. My people don’t mind.” So in the Main Theatre, which is now the John Kani, I put my hand below her breast, and there was the biggest silence I have ever heard in the theatre. I put my hand up, because I am tilting back, pretending there is something in my eye. So that she could lean over me, and her breast is almost on my face. And I touch her breast. And I hear this one “Oh God!” And she grabs me. It was Sandra who kissed me! I’m a servant, see. I say, “No, ma’am, leave me alone”, and Sandra goes, “Mwah”, and she keeps it that way. And jirre jong, the exit doors were opened. Two hundred people, led by the late Professor Lincoln Boshoff, walked out of the theatre. The other theatregoers stayed and booed them. We went backstage and we came back. The part they were objecting to was not the kiss.

Ruda: It was the touching?

John: More than that. We run offstage and I come back, pulling my zip up. And Sandra comes in holding her panties and her pantyhose in her hand. So what freaked them out is what they think happened backstage!

Ruda: Yes, it’s the implication.

John: We didn’t do anything! But we had an incredible run – apart from the fact that every night we would get bomb threats. We’d get a call that there’s a bomb. Colonel Tait from John Vorster Square, the bomb squad, would come with the sniffer dogs. I had a person who drove with me. Sandra was protected too once she got into her car. We decided not to give Sandra the hate mail, because it was terrible. It was terrible, terrible hate mail.

Ruda: What did that mean to you?

John: Excitement. I like a play that creates a conversation, that creates an interaction and engages the audience. I didn’t do it to annoy or to be part of protest. It was a great play and I had an opportunity to work with a very, very good actress, Sandra Prinsloo. But this was the eighties, this is the high point of the United Democratic Front. Black and white people were coming together voicing their objection to the system of apartheid. Suddenly the opposition to apartheid was not black. It was just the people of South Africa. It was exactly at that time that Miss Julie, followed by Othello in 1987, happened, in that political climate. Where somehow even artists stood up and said, “I too, I want to be counted.”

Ruda: It became a symbol.

John: (Nods) It became a symbol. And that I enjoyed very much. But then, when we came to 1987, my wife said, “No. No. You nearly died during that play.”

Ruda: You were attacked and almost killed, right?

John: Ja, eleven stab wounds around my body, my face, my back. So my wife said, “You’re not doing this one. It’s not just a play. You know this play, and Desdemona. You know that you’re going to be in a love relationship here.” I said, “It’s a moment in my life. To play this great role, Othello, the classic, directed by Janet Suzman, from England. Don’t worry, there won’t be any problem. At least this time they know it’s Shakespeare.” Oh my God.

Ruda: Was it just as bad?

John: Not as bad as Miss Julie, but there was a bit of reaction from the audience. Very few of them walked out. But they watched. That’s because they wanted to see the moment.

Ruda: But with Othello, you know that is what’s going to happen. That’s what the whole thing is about. So the audience was prepared.

John: They knew what was going to happen. Then suddenly, one day when I came back from the theatre, the security police stopped at my home in Soweto. “Can we ask you a few things?” they said. “Who decided to do this play?” And I thought, I’m going to say, The Market Theatre, not me. I am just an actor. But I was the artistic director of the Market Theatre, so I couldn’t get away with it. And the policeman says, “Why did you choose the play?” And I said, “Look, in the life of an actor, you have to do the classics if you really want to enhance your career.” Then he said, “But tell me something. On page 17, you are with the duke who is going to tell you to go and fight the war outside. Your wife comes in, right? And you . . . you kissed her. It doesn’t say that; why did you do it?”And I thought, “He read the book! Die poliesman het die play gelees!7 He read the play.” I was so happy. And then finally he says to me, “In the bedroom, when you were killing her, you were wearing nothing but a little loincloth. And you straddled your whole body over her beautiful white body. Why did you do that?” So I thought I’d be a little smart and I said, “Remember in the sixties, when Maggie Smith and Laurence Olivier played the same parts? Laurence was covered in black make-up to look black. They couldn’t kiss, they couldn’t be sensual, because that make-up . . .”

Ruda: It would rub off!

John: “ . . . it would rub off on Maggie’s white dress and Maggie’s face,” I said. “I don’t have that problem.” And he looked at me, like, next! But finally he let me go. We filmed the play and it was shown in England. It was very well received. In fact, it made me recognised as one of those “greatest African Shakespearean actors”. It was an incredible experience for me.

Ruda: Against that background, how did you personally experience the transition in 1990?

John: It was an incredible time in our lives. Remember, the release of Nelson Mandela happened when the entire country, especially the black communities, had been rendered ungovernable. I had been living in a house, and I couldn’t pay rent or electricity for six years. I couldn’t pay even if I wanted to, because the offices for rent were burnt down. Nobody would come and cut electricity. The rioting around the communities was incredible.

I remember at night I would wake up and hear the Casspir trucks that used to patrol our township. And then one night I didn’t hear them. I got worried. I almost said, “Where are the soldiers? I need to hear them to harass me or to look after me.”

And suddenly Nelson Mandela walks out [of prison]. He makes that speech in Cape Town, and he is asking us to give him a chance, saying that if he could, through negotiation, save one life, it would be the greatest achievement. But we needed to trust him.

We didn’t know what he meant exactly but we said yes. What followed then, right up to the death of [ANC leader] Chris Hani in 1993 . . . was the violence in our townships of the Third Force8 or Fourth Force or Sixth Force . . . but at the elections of the 27th [April 1994] we had to re-emerge as a different people. We had to come out as black people with an understanding that there is a better future that could be here for us.

We even had to believe in this thing called the vote. Remember, we fought for freedom, we fought for liberation. Now we were told about something we had never heard of: democracy. Excuse me? Explain this thing, what is democracy? It means we are not going to kill all the whites. It also means we’re not going to chase them all out of the country, because we need them. It means there are a number of good black people and good white people that will come together, and take this country to the future of equality, of equal opportunities or something. We bought into it like that, and it was amazing.

I remember 1994. I took my whole family, young, four, five of them, the girls, the boys, to vote. They didn’t vote, I just wanted them to experience it.

Ruda: How old were they?

John: They were . . . sixteen, the other was nine, the other one twelve. The press came, CNN came, the BBC came. They wanted me at the front of the queue so they could take a picture of me voting. I didn’t write anything on the ballot. I didn’t vote; I just put the empty clean ballot paper in the box, because I wanted to stand in the queue. So they took the photograph, and I went back to the queue. I asked my son, “Where is your mum?” “No, Mum has gone home quickly with the car. She is going to make sandwiches for us.”

John: And the white family [near us], who only had two children, had nice sandwiches and suddenly the white woman was distributing sandwiches to my children as well. I was about to say, “You can’t take bread from white people!” So the macheesa . . . yum yum . . . there we were, talking to them in English. My wife arrives and distributes the sandwiches, and then my children break the pieces and give them to the other white children in the line. I thought, “This is too fast for me. I am still too angry, can you please slow down with this integration? I’m not ready yet.”

I walked in, a little ink, my ID, I put in my cross – I am not telling you where, it’s mos my secret nè, ja, it’s my secret. I put the ballot in the box and I walk out. Ruda, ek was so kwaad. So kwaad. Hoe kan dit so maklik wees?9 To change things in my beautiful South Africa. Vir jare ons het gebaklei, mense10 . . . my own brother was shot in 1985. It can’t take just an X with a pencil on a piece of paper to change that. I had imagined voting was going to be the most difficult process. It was as simple as an X. And I put it there, and I said to my wife as we were driving home, “I am nervous.” She asked, “Why?” I said, “We have a bigger task now. To look after this newborn democracy. How are we going to do this?”

Because we had to get the entire nasie [nation] to buy into it. How are we going to do this? While we are struggling with that, here were Nelson Mandela and F. W. de Klerk and Bishop Tutu with another thing, called truth and reconciliation. Nee, wag, ek wil weet wie het my getorture when I was detained ten or twelve times. Ek wil weet wie het my broer geskiet.11 But no, there is a new way of doing this. It is reconciliation. It took time. Real time.

It took me from 1996 up to 2002 to really forgive, by writing the play Nothing But the Truth. It was a tribute to my brother, because I could now think about him, not as a dead body with three bullets through his stomach, but as a militant who was shot because he was a poet, and reciting a poem at a funeral of a little girl who had been hit by a tear-gas canister. I walked out of Grahamstown in that performance, the 4th of July 2002, almost like . . . reborn. I truly became a South African. A proud South African.

In 2016 John and Sandra Prinsloo teamed up again for the Afrikaans version of Driving Miss Daisy.

John: I get a call from [theatre producer and playwright] Saartjie Botha, who says to me, “We have an idea. Driving Miss Daisy in Afrikaans.” I said, “But I am not sure about my Afrikaans.” She said, ‘Nee, man, moenie nonsens praat nie, jy praat goed Afrikaans.’12

John: So we start. En Saartjie werk met my in die Afrikaans, die Afrikaans wat ek kan praat. En toe sê ek vir haar, “Nee, translate the script as you wish. Let me learn.” En toe werk ons vir vier weke, die translations and the rehearsals. Ek voel ’n bietjie comfortable met die Afrikaans. Nou by die Aardklop in Potchefstroom, ons eerste . . .13

Ruda: Nou is jy in die hart van Boeredom.14

John: Ooh . . . the first performance, nine thirty in the morning! We had never even had a run-through of the piece. The hall seats about 425 people. And I thought, if we get fifteen or sixteen I will be happy. The lights come up. (Throws up his arms) It is a wall of white people. Couple of black people (points) there and there.

You know what we do on Broadway: when a star makes an entrance, he or she gets a round of applause and then the play continues. And the first part of the scene is between Jacques Bessenger and Sandra. The son says to Miss Daisy, “You need a driver.” Now he’s going to interview me. It’s the second scene. I step in. Thunderous applause. It stopped. I thought, please hold on to the language [the Afrikaans]. At the end it was incredible. Toe wag die mense buitekant vir Sandra en my.15 To shake our hands. They talked about my whole career in theatre, where they had seen me, which film, whatever. Young people said, “We saw you recently in Captain America: Civil War. That’s why we came this morning.” Maar toe sê die mense, “Can you give me your hand?” I said, “Shake hands,” en toe sê die ou lady, “Ag, maar gee my sommer ’n druk.”16 It was unbelievable.

What more can I ask for in my life than an incredible career, incredible growth? I have grown with this country. From the worst of this country to the best of this country. I’ve just come back from a tour with my last play, Missing, which I also wrote. In Bogotá, Colombia, they are trying to make peace – FARC [Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia] and the government. Those people have fifty years of fighting, of killing. When I was there, I was invited to the university to speak to five hundred students [in an auditorium], three times in a row. All they wanted was for me to explain truth and reconciliation. They were asking me, “You had suffered. I have read your bio, your history. How could you accept white people? How did you accept forgiveness?”And you say, “It was a natural phenomenon. You fought not for revenge, you fought for peace.”