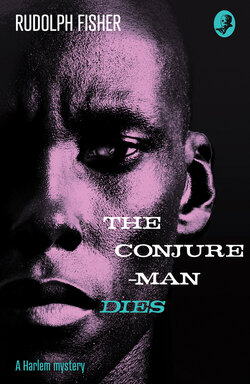

Читать книгу The Conjure-Man Dies: A Harlem Mystery - Rudolph Fisher - Страница 10

CHAPTER IV

ОглавлениеMEANWHILE Jinx and Bubber, in Frimbo’s waiting-room on the second floor, were indulging in one of their characteristic arguments. This one had started with Bubber’s chivalrous endeavours to ease the disturbing situation for the two women, both of whom were bewildered and distraught and one of whom was young and pretty. Bubber had not only announced and described in detail just what he had seen, but, heedless of the fact that the younger woman had almost fainted, had proceeded to explain how he had known, long before it occurred, that he had been about to ‘see death.’ To dispel any remaining vestiges of tranquillity, he had added that the death of Frimbo was but one of three. Two more were at hand.

‘Soon as Jinx here called me,’ he said, ‘I knowed somebody’s time had come. I busted on in that room yonder with him—y’all seen me go—and sho’ ’nough, there was the man, limp as a rag and stiff as a board. Y’ see, the moon don’t lie. ’Cose most signs ain’t no ’count. As for me, you won’t find nobody black as me that’s less suprastitious.’

‘Jes’ say we won’t find nobody black as you and stop. That’ll be the truth,’ growled Jinx.

‘But a moonsign is different. Moonsign is the one sign you can take for sho’. Moonsign—’

‘Moonshine is what you took for sho’ tonight,’ Jinx said.

‘Red moon mean bloodshed, new moon over your right shoulder mean good luck, new moon over your left shoulder mean bad luck, and so on. Well, they’s one moonsign my grandmammy taught me befo’ I was knee high and that’s the worst sign of ’em all. And that’s the sign I seen tonight. I was walkin’ down the Avenue feelin’ fine and breathin’ the air—’

‘What do you breathe when you don’t feel so good?’

‘—smokin’ the gals over, watchin’ the cars roll by—feelin’ good, you know what I mean. And then all of a sudden I stopped. I store.’

‘You whiched?’

‘Store. I stopped and I store.’

‘What language you talkin’?’

‘I store at the sky. And as I stood there starin’, sump’m didn’t seem right. Then I seen what it was. Y’ see, they was a full moon in the sky—’

‘Funny place for a full moon, wasn’t it?’

‘—and as I store at it, they come up a cloud—wasn’t but one cloud in the whole sky—and that cloud come up and crossed over the face o’ the moon and blotted it out—jes’ like that.’

‘You sho’ ’twasn’t yo’ shadow?’

‘Well there was the black cloud in front o’ the moon and the white moonlight all around it and behind it. All of a sudden I seen what was wrong. That cloud had done took the shape of a human skull!’

‘Sweet Jesus!’ The older woman’s whisper betokened the proper awe. She was an elongated, incredibly thin creature, ill-favoured in countenance and apparel; her loose, limp, angular figure was grotesquely disposed over a stiff-backed arm-chair, and dark, nondescript clothing draped her too long limbs. Her squarish, fashionless hat was a little awry, her scrawny visage, already disquieted, was now inordinately startled, the eyes almost comically wide above the high cheek bones, the mouth closed tight over her teeth whose forward slant made the lips protrude as if they were puckering to whistle.

The younger woman, however, seemed not to hear. Those dark eyes surely could sparkle brightly, those small lips smile, that clear honey skin glow with animation; but just now the eyes stared unseeingly, the lips were a short, hard, straight line, the skin of her round pretty face almost colourless. She was obviously dazed by the suddenness of this unexpected tragedy. Unlike the other woman, however, she had not lost her poise, though it was costing her something to retain it. The trim, black, high-heeled shoes, the light sheer stockings, the black seal coat which fell open to reveal a white-bordered pimiento dress, even the small close-fitting black hat, all were quite as they should be. Only her isolating detachment betrayed the effect upon her of the presence of death and the law.

‘A human skull!’ repeated Bubber. ‘Yes, ma’am. Blottin’ out the moon. You know what that is?’

‘What?’ said the older woman.

‘That’s death on the moon. It’s a moonsign and it’s never been known to fail.’

‘And it means death?’

‘Worse ’n that, ma’am. It means three deaths. Whoever see death on the moon’—he paused, drew breath, and went on in an impressive lower tone—‘gonna see death three times!’

‘My soul and body!’ said the lady.

But Jinx saw fit to summon logic. ‘Mean you go’n’ see two more folks dead?’

‘Gonna stare ’em in the face.’

‘Then somebody ought to poke yo’ eyes out in self-defence.’

Having with characteristic singleness of purpose discharged his duty as a gentleman and done all within his power to set the ladies’ minds at rest, Bubber could now turn his attention to the due and proper quashing of his unappreciative commentator.

‘Whyn’t you try it?’ he suggested.

‘Try what?’

‘Pokin’ my eyes out.’

‘Huh. If I thought that was the onliest way to keep from dyin’, you could get yo’self a tin cup and a cane tonight.’

‘Try it then.’

‘’Tain’t necessary. That moonshine you had’ll take care o’ everything. Jes’ give it another hour to work and you’ll be blind as a Baltimo’ alley.’

‘Trouble with you,’ said Bubber, ‘is, you’ ignorant. You’ dumb. The inside o’ yo’ head is all black.’

‘Like the outside o’ yourn.’

‘Is you by any chance alludin’ to me?’

‘I ain’t alludin’ to that policeman over yonder.’

‘Lucky for you he is over yonder, else you wouldn’t be alludin’ at all.’

‘Now you gettin’ bad, ain’t you? Jus’ ’cause you know you got the advantage over me.’

‘What advantage?’

‘How could I hit you when I can’t even see you?’

‘Well if I was ugly as you is, I wouldn’t want nobody to see me.’

‘Don’t worry, son. Nobody’ll ever know how ugly you is. Yo’ ugliness is shrouded in mystery.’

‘Well yo’ dumbness ain’t. It’s right there for all the world to see. You ought to be back in Africa with the other dumb boogies.’

‘African boogies ain’t dumb,’ explained Jinx. ‘They’ jes’ dark. You ain’t been away from there long, is you?’

‘My folks,’ returned Bubber crushingly, ‘left Africa ten generations ago.’

‘Yo’ folks? Shuh. Ten generations ago, you-all wasn’t folks. You-all hadn’t qualified as apes.’

Thus as always, their exchange of compliments flowed toward the level of family history, among other Harlemites a dangerous explosive which a single word might strike into instantaneous violence. It was only because the hostility of these two was actually an elaborate masquerade, whereunder they concealed the most genuine affection for each other, that they could come so close to blows that were never offered.

Yet to the observer this mock antagonism would have appeared alarmingly real. Bubber’s squat figure sidled belligerently up to the long and lanky Jinx; solid as a fire-plug he stood, set to grapple; and he said with unusual distinctness:

‘Yea? Well—yo’ granddaddy was a hair on a baboon’s tail. What does that make you?’

The policeman’s grin of amusement faded. The older woman stifled a cry of apprehension.

The younger woman still sat motionless and staring, wholly unaware of what was going on.