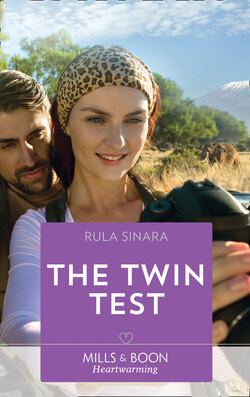

Читать книгу The Twin Test - Rula Sinara - Страница 12

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

THEY WERE MISSING.

Dax Calder muttered a curse and tossed his laptop, satellite phone and several rock samples, on the hand-carved poster bed that occupied the bungalow’s main living space. He double-checked the adjoining bedroom, where his identical twin daughters were supposed to be waiting for him.

The room was in perfect order, down to their suitcases—one purple and one green—sitting uncharacteristically neat and aligned at the ends of their timber-pole framed beds. Two binders of math practice assigned from their virtual classes lay on a small writing table tucked in the far corner. He had a feeling the twins hadn’t touched a math problem since he’d left them three hours ago. Sheer white curtains danced over a colorful, handwoven tapestry rug in front of the sliding doors which led to a private, lava stone patio.

Escaped. Not kidnapped. Or killed. Or—God help him—eaten alive.

He raked back his hair and started for the open door. His flash of panic dulled to a smoldering irritation the second he spotted a piece of paper with a pair of cheeky smiley faces drawn on it taped to the glass behind the billowing sheers. Not again.

Their modus operandi. Cryptic notes. Nothing but the sketched faces and “bored x 2” written under them. How many times had he told them that they needed to stay put until he returned? Three hours was all he’d asked for out of desperation. Their nanny hadn’t arrived in Kenya yet, and the chief engineer overseeing the oil field extension Dax had been contracted to survey had set up a meeting this morning.

Dax ripped the paper down and crumpled it. It wasn’t the first time he’d dealt with their escapades. Using their twin factor to play pranks with hotel staff whenever he traveled was probably half the reason the hotels he frequented knew him so well. He wouldn’t be surprised if his name was tagged with a warning note: Beware of the twins.

Only he’d never stayed here at the Tabara Lodge before. Heck. They’d never stayed anywhere this exotic. He wasn’t worried about them sneaking into a hotel kitchen and switching the salt and sugar, or dressing up as the Grady twins from The Shining and knocking on random hotel room doors at night. No, at the Tabara Lodge he was more worried about what they’d run into. This was Africa...as in safari land.

As stunning as Kenya was, there was dangerous wildlife out there, and the girls’ idea of survival and self-preservation was limited to some pact they had never to rat on each other.

Dax tugged at the collar of his polo shirt, where it chafed the back of his neck. He paused only for a second to secure the door they’d left open.

He’d told them a million times to keep the bungalow locked up so that nothing would get stolen. He’d expected them to stay locked in because it made him feel more secure about leaving them alone for a few hours. Sure, he’d chosen Tabara because it was family friendly and had flushing toilets. But the guests and staff were still strangers. He had also been warned that wildlife here could be unpredictable and that vervet monkeys considered open doors an open invitation. He made a mental note to check his bags and equipment for anything missing—once he found his missing kids.

An area of flowering shrubs and fruit trees that shaded benches fashioned from thick, twisted branches, extended beyond the rustic stone patio. Twelve thatched-roof bungalows, joined by stone-lined dirt paths, sat in a semicircle around the main lodge, complete with reception area, restaurant and pool. Considering the view of the golden savanna in the distance, this upscale safari lodge watered its gardens well. It seemed a wasteful luxury for a region that suffered severe drought seasons, but then again, for what he was paying for an extended stay, the lodge could afford the extra water.

Water. He knew exactly where to look for them first—the one place he’d forbidden the twins to go alone.

He headed for the main lodge, rounding a small cove where urns of flaming red hibiscus surrounded a metal sculpture of a giraffe and its baby. The scent of pool water and earsplitting squeals hit him before he cleared the garden.

“Out. Now.”

“Dad! Jump in!”

Ivy disappeared under the water and shot across the pool so quickly that all he could make out was a blur of purple. Fern popped her head out of the water and pulled one of her green swimsuit straps higher on her shoulder.

Sandy had chosen the two colors when she was planning their nursery and outfits before they were born. The purple-and-green color coding had stuck as a way of telling the identical twins apart and, even now, the girls considered them each their favorite colors because their mother had chosen them. As for Dax, it made life a lot easier when he wasn’t wearing his contacts or when he was too tired to pay attention to their subtle differences, like the fact that Fern had always weighed a pound or two less than Ivy.

“Not happening. Now, both of you, out.”

He grabbed a complimentary towel from a stack and tossed it to Fern as she hoisted herself onto the edge of the pool. Ivy hedged her bets and flipped around for one more lap before obeying.

“You’re not really mad, Dad,” Fern said, wrapping her wet arms around him. “Are you? Because I’d feel guilty, and you know how that knots up my stomach and makes it so I can’t eat.”

Guilt trip, huh? He loved them to death, but these two were going to age him twice as fast. Make that four times as fast if they’d inherited their ability to guilt him into doing what they wanted from his mother.

“I totally am, and I would never make you eat if you weren’t up to it.” Dax tossed another towel at Ivy as she dripped on over to them. “So glad you could finally join us.”

“Oh, come on, Dad. Didn’t you have ‘physical education’ written on the schedule you made up for our nanny? Since she’s not here yet, we figured we should get it done anyway, like the responsible individuals you’re raising us to be,” Ivy said.

“Yep, we’re on time and everything. In fact, isn’t math up next, Ivy?”

Fern smiled at her sister, and something unspoken passed between them. He couldn’t put his finger on it, but his parental instincts screamed conspiracy. Was math a code word or something? Man, he wished he could tap into their telepathic twin phone line. He narrowed his eyes and put a hand on each of their shoulders when they tried slipping past him.

“Math and reading were the only things you were supposed to do the past three hours. That and staying put.”

“But the power went out again,” Fern said.

That would make it twice since they’d arrived yesterday—if she was telling the truth. Being at the mercy of generators was something they’d have to get used to during their stay here.

“You don’t need power. Your math was printed out and there’s plenty of sunlight for reading.”

They started to argue and he cut them off.

“I’m not kidding, you two. I set your ground rules to keep you safe. Swimming without supervision isn’t okay—”

“But we’re good swim—”

“Don’t interrupt me, Ivy. I don’t care if you’re Olympic gold medalists. Things can happen. You could hit your head jumping and get knocked unconscious in the water. Or something even worse. And everyone here is a stranger—staff and guests. What if there was a creep hanging out here? Or a wild animal?”

There wasn’t even a lifeguard on duty, for crying out loud.

The images he’d seen of the South Asian earthquake-triggered tsunami that killed thousands—including families on vacation, lounging around pools—flicked through his mind. He’d been a sophomore in college at the time, and his friend had been on vacation in Indonesia. He’d died in the tsunami, along with his parents and sister.

The entire family. Gone. Unexpectedly.

The tragedy had hit Dax hard, eclipsing the other disasters ruining his life at the time, like his girlfriend dumping him and his parent’s divorce announcement.

He hated the unexpected.

Dax sucked in a deep breath, rubbed the base of his throat, then put his hands on his hips.

The tsunami was a memory. The past. The reason he’d decided to study quakes. To save people. To stop natural disasters from shaking and tearing lives apart like fissures in the crusty earth. It wasn’t something he talked about, especially not to the girls.

“We’re at a lodge, Dad. I think we’d need to go on a safari to see the wild animals.” Fern folded her arms and shifted her weight to one side. They’d been begging for him to take them on a safari, once they arrived in Kenya, but he didn’t have time for one yet. They weren’t here on vacation. He had work to do. People to answer to.

“Should I forward you the article I read about an elephant that kept breaking onto hotel grounds to drink from their pool? Besides, if gators and snakes can make it into toilets and pools in Florida, then I wouldn’t be surprised if something more dangerous slinked into a pool out here. And by dangerous, I mean more dangerous than the two of you.”

“Very funny.” Ivy grinned. “So, when’s Number Seven supposed to get here?”

“That’s Miss Melissa, to you. Don’t you dare call her Nanny Number Seven. She has no idea how many you’ve been through. Unless you told her.”

“Why would we do that?” Ivy pursed her lips as if to keep from smiling as she dried her hair.

There was that fleeting exchange between them again. Dax pinched the bridge of his nose, then raked his hair back.

Melissa had been with them only a week before he’d signed this contract with Erebus Oil. The contract had been an offer he couldn’t refuse. Due to his expertise and reputation as a seismologist, they were paying him more than he’d ever make in research...even more than he’d made on his last two jobs in the petroleum industry. And the living allowance Erebus offered as incentive was helping him afford Tabara Lodge. He’d told them upfront that he’d need a living situation amnenable to bringing his daughters along. That part of the deal had been nonnegotiable. His daughters and their nanny couldn’t live on-site in trailers, like the rest of Dax’s crew would be doing. He was lucky Melissa had agreed to come with them, and he’d gone over the arrangement with her multiple times. Of course, he had paid for her ticket from Texas, too.

Then he’d bribed the girls.

For every month the nanny stayed, he’d give them an allowance bonus. If their nanny quit, he’d dock their allowance. Reimbursement for his time and trouble. So far, so good.

“Miss Melissa should be here tonight. I was about to check for any flight delays when I returned from my meeting, but as luck would have it, I ended up looking for the two of you. You left the room unlocked, by the way. Strike two. Let’s go.”

“Oops.” Fern linked her arm in Ivy’s and the two vanished down the garden path toward their room. He heard them giggling to each other. Laughter was supposed to be a happy sound, not a worrisome one. He scrubbed his face and shook his head.

“It’s been less than forty-eight hours since you left home, Dax. Man up. You’ll survive,” he muttered. A little sleep wouldn’t hurt. His exhaustion and preoccupation with work gave the twins the advantage. How was it the girls seemed immune to jet lag? He needed a nap but didn’t dare take one. Unless, perhaps, he kept one eye open.

More laughter rang out as he started down the path after them, only this time it didn’t sound like the twins, and it was coming from—

He looked across the pool and beyond an arched stone arbor that led to an outdoor, canopy-covered seating area for the lodge’s restaurant. A woman with wildly curly auburn hair and an equally radiant smile walked past the tables and mass of fig trees that divided the dining and pool areas, making odd gestures with her arms as she spoke. There. He was right to warn the kids that everyone here was a stranger and some were a bit off in the knocker.

A brood of six blond-haired kids emerged from behind the curve of the lodge’s wall, following her like she was the Pied Piper. Okay, so she wasn’t talking to herself, but still, one had to be just a tad nuts to have that many kids. He could barely handle two.

He stuck his hands in his pockets and returned to the bungalow. Reassured by the sound of the twins’ voices in their room, he went straight for his laptop, hoping the lodge’s wifi wouldn’t fail him. It was yet another reason he’d booked this place. Most lodges only offered it in the lounge and restaurant.

The first few emails were from Ron Swale, the chief engineer he’d met with earlier at the survey site. The not-so-subtle yet diplomatic reminder that any seismic data Dax and his team collected was for the purpose of analyzing and mapping the possibility of oil pockets in a field extension near Erebus’s current wells—not research—had set his blood to simmering. It had taken everything in him not to walk away, but he’d signed a contract and his crew was counting on him for their jobs. He needed the income, as well. The fact was, he’d cleared collecting a little seismic data on his own time with management when he’d signed on for this. He’d never been close to the Greater Rift Valley region before. Not studying the area while he was here would be like forcing a kid to walk through miles of toys and not be allowed to touch even one.

Ron’s condescension might have irked him, but it was guilt that really gnawed at Dax.

Giving up on researching earthquake prediction hadn’t been a choice, it had been a necessity. And now any research he did was in the name of serving the oil company.

He knew about the relatively recent uptick in tremor activity in the area, some too weak for anyone to feel, but environmental groups were beginning to make waves. The same anti-fracking environmental groups Sandy used to support. Most oil companies insisted post-fracking water injections had nothing to do with increases in seismic activity.

Dax wasn’t so sure. Yet, here he was. That made him an enabler, didn’t it? But he had debts to pay off and the girls to raise and working for a petroleum company paid well. Six-figures well, which was more than double what he’d been pulling in before from research grants.

Don’t overanalyze. It’s a steady job. Just do it. But “doing it” meant he required full-time help with the twins more than ever. He rubbed the back of his neck as he scrolled down the emails in his inbox, finally spotting one from Melissa. He needed her here yesterday. He opened the email, but the knots in his neck only tightened. You’ve got to be kidding me.

“Ivy! Fern! Come in here. Now.”

The carved wood door to their room swung open and the two appeared dressed in shorts and T-shirts with their wet hair loose and half-combed out. Their eyes flitted toward his laptop and back up to him, widening just enough to look innocent.

“What’s up?”

“Nanny Number Seven quit. What do you two know about this?”

“I thought we weren’t supposed to call her that,” Fern said.

“I’m a little upset here, so I’ll call her Seven if I want to, especially since I now have to take time I don’t have to search for Eight.” He was sounding just like the twins. He squeezed his eyes shut and inhaled, long and deep.

“He’s at a 5.0,” Ivy muttered. “We’ll live.”

“Are you kidding? His neck is red. That puts him at a 6.5,” Fern countered.

Dax ignored their habit of using the Richter scale to gauge how mad he was at their shenanigans.

“It says in her email that the giant spider in her purse was the last straw.”

“It was fake. Besides, that’s such an overused prank, she should have expected it. She’s just a wimp. So much for her acting all sergeant-like. All bark and no bite. And she’s lazy—anyone who uses that as an excuse to quit doesn’t really want to work,” Ivy said.

“And you two certainly are a job.” He had no doubt the spider had only been a warm-up for the twins. A test. It didn’t come close to their somewhat scary creative capacity.

“It was harmless, Dad. We pulled it out of our Halloween supplies. We were just having fun. Fun is a necessary part of raising well-rounded, healthy, psychologically balanced children,” Fern added.

Wow. Just wow.

He closed his laptop. Three years and he still had to pause and ask himself what Sandy would do. Only lately, he kept coming up blank. She didn’t even visit in his dreams anymore...not the way she had after she’d left him and kept the girls. They had been five at the time.

Looking back, he couldn’t blame her for leaving. She’d been right. He’d been too busy chasing after his obsession to find better ways of predicting earthquakes and saving lives. He’d spent more time in tents doing field research than he had at home, protecting his family.

But he had tried to make it up to her. He’d been as present as he could possibly be after her diagnosis...but it had been too late.

He checked his watch again. He was supposed to be at the site by midmorning tomorrow to start setting up equipment, laying out geophones and cables. But now he had no nanny and there was no way he was taking the girls to the site. Too dangerous and not allowed.

He stared pointedly at each one. They looked so much like their mother all three could have been triplets, but for the generation gap. Their hair had lightened back to dark blond as it dried, and their hazel eyes sparkled with hints of gold that matched the freckles on their noses. That reminded him to pull out the sunscreen from their bags.

“Ivy. Fern. You need to think before you act. Everything you do has consequences.” Now he was sounding like his mother. He cringed. “That fake but—according to your nanny—very realistic spider caused her to scream and jolt. That caused her to spill her hot coffee all over her hand and into her purse, which resulted in both a burned hand and a fried cell phone, which I’ll be paying to replace. Nope. Correction. Which you’ll be paying to replace.”

Ha. There was an inkling of parental genius in him yet. The twins crinkled their foreheads, and the corners of their mouths sank.

“We’re really sorry,” they said simultaneously. It almost...almost...sounded rehearsed. Like synchronized swimming. Maybe he should look into signing them up for a class. Burn off some of that energy.

“Apology accepted.”

“So how do we earn the money to pay for her cell phone? We need jobs, right?” Fern asked. Always the logical one.

Jobs. He hadn’t thought that far ahead. Darn it. At their now-rented-out house in Houston, he could have had them weeding for the neighbors. But here? No way were they sticking their hands under shrubs where predators could be lurking. Not that the lodge needed any help with weeding. There were no jobs for eleven-year-olds here, not even lemonade stands or bake sales or... It hit him. That was Fern’s not-so-innocent point. No job availability. They were trying to get out of paying. Not happening. He scratched the back of his neck and stood up.

“You’ll stick to our bargain regarding your next nanny. Behave and you’ll get an allowance bonus. Consider yourselves docked for losing Melissa, so you’ll have to earn that back, too. And for now, your allowance goes to paying it off. Plus, I’ll pay a few extra bucks for keeping your room clean, beds made and bathroom wiped down.”

“Sounds fair,” Ivy said.

“Good. Now go brush out your hair and get your shoes on so we can get a bite to eat.”

The two closed their room door behind them, and Dax leaned his head back against the wall. The tribal mask hanging over his bed on the opposite side of the room scowled at him, as if it disapproved of his parenting skills. This was going to be a long day.

He started to head for his bathroom, but their whispers stopped him. He didn’t mean to eavesdrop—or maybe he did. The words he picked up required listening to. It was his parental duty.

“Doesn’t he realize?” That was Fern.

“Are you kidding? Maybe there’s an advantage to him being too busy to pay attention to us most of the time. It makes it easier to get away with things.”

“Yeah, like the fact that, technically, he’s the one paying for the broken cell phone. If you take into account that cleaning up is part of getting our allowance to begin with, then add the bonus for doing so, it covers what we were docked and then some.”

“And on top of that, we have a little freedom before he hires us a supervisor. But do you think we should get rid of the worms we put in his shaving kit before he opens it in the morning? If he docks us for that, we’ll be in the red.”

“You’re right. He hates worms about as much as Number Seven hates spiders.”

My shaving kit?

Dax gritted his teeth and eyed his toiletry bag. He’d always wanted to try the short-stubble look.

God, he needed to focus on his job, not the twins’ antics. He needed to be able to work without worrying. He’d made a lot of sacrifices to get through the past few years, but having the twins grow up away from him was where he drew the line.

He’d promised Sandy that he would stay with them. Keep them safe. Their grandparents disagreed with him moving them every time his job took him somewhere for months. They had insisted that the girls required structure and time management. As far as he was concerned, he could provide that. Sticking to a schedule wasn’t rocket science.

He just had to find a nanny who could do it.

* * *

PIPPA HARPER TUGGED against the stiff leather of her watch band and finally forced it to unbuckle. She shuddered as she shoved the new gadget in the pocket of her khakis and rubbed the imprint it left on her wrist. If anything ranked up there with flies and mosquitoes buzzing persistently around her face or deceptively delicate ants forging a trail up her back during a relaxing nap under the Serengeti sun, it was wearing a watch or following someone else’s schedule.

She unfolded a handwoven, flat-weave rug over the dusty, red earth that flowed through the small Maasai village enkang and beyond its thorny fence, then stretched out on her stomach and propped herself up on her elbows. The tribe’s oldest child, Adia, sat down next to her. At thirteen, she was making huge progress with her fourth-grade-level reading and writing. Pippa was proud of her.

“I’m ready and listening,” Pippa prompted with a smile. Adia was used to her relaxed teaching style. Of course, she sat up and gave the lesson more structure when they were writing or doing math, but reading was different. Reading was meant to be enjoyed. She wanted the kids to see that.

Adia opened the book to her marked paged and began reading. Her musical lilt drew Pippa into one of her favorite storybooks. The girl had a future ahead of her, so long as her father agreed to let her leave home and continue her education beyond what Pippa could offer. Trying to teach the children of the Maasai and other local tribes—particularly the young girls, who weren’t always given the opportunity—was a lot for one person. Thankfully, she wasn’t the only teacher who was trying to help. Some well-known people from the university...some who were born in these villages...had programs to teach and give back. But a few people and a couple of programs weren’t enough to teach all the rural children in Kenya and the children in the tribes around here were counting on her. She needed more money to help them. She was spread thin, traveling on different days to different enkangs. At some point, the girls had to be given the chance to move beyond her limitations.

She closed her eyes and raised her face to the sun as she listened. It felt so much better not to have her watch on. Who needed clocks when they had the sun and stars? Who needed alarms and schedules when all they had to do was listen to the diurnal rhythm and sounds of wildlife announcing everything from daybreak to dusk to the coming of rain?

Rain, fluid. Earth, solid.

The simple facts flashed through her mind the same second that the ground rippled against her like a river current against the belly of a wildebeest trapped during the floods.

She stilled and pressed her palms against the rug, her mind registering fact and logic. Earth. Solid. She glanced around. Adia’s rhythm hadn’t faltered. The others in the village were going about their routines.

The herdsmen had taken their cattle and goats out to pasture, and the enkang’s central, stick-fenced pen, where their goats were kept safe from predators at night, stood rigidly against the backdrop of the Serengeti plains. Women were laboriously mashing dried straw with cow dung and urine for the mud walls of their small, rounded inkajijik. Simple homes made with what the earth offered. The solid earth.

Clearly, she’d imagined the ripples. No one else seemed fazed. Maybe the sun was getting to her. It had shifted in the sky, stealing away the shade that the branches of a fig tree had offered. She took a deep breath and sat up, brushing off her hands, then pushing her curly hair away from her forehead.

“Is everything okay? Should I stop reading? Did I make a mistake?” Adia fingered the rows of red and orange beads that graced her neck, then smoothed her hand across the vibrant patterns of her traditional wrap dress.

“No, no. It wasn’t you. I need to get out of the sun.”

There was no point in frightening the girl. Unless... No, she doubted it. She hadn’t felt a tremor in forever. Sure, they happened here. She’d studied geology as an undergrad. She knew all about the earth’s tectonic plates moving.

She’d felt mild quakes in the past. The Great Rift Valley ran through western Kenya, including the Maasai Mara and the area where the Serengeti ecosystem lay and merged across the border into Tanzania’s famous Serengeti National Park. There was more earthquake activity in that region, but minor events happened here, too. Even to the east in Nairobi.

But what had happened a minute ago had been a different, odd sensation. Nothing had shaken. No one else had noticed. Most likely, the sun had made her dizzy. She got up and sat upright next to Adia.

“Okay, you can keep reading. Let’s get to the end of the chapter before we stop. That way you can write me a summary for next time.”

Adia looked down uncomfortably and bit her lip.

“What is it?”

“I shouldn’t ask you for more.”

“Adia, if you need something, ask me.”

“I can’t write a summary. A goat ate the pencil and paper you gave me. I set it down to help my sister when she fell down. And then the goat ate it.”

Pippa gave her a reassuring smile. If this had been anywhere else and a student had told her teacher that the dog had eaten her homework, she would have been accused of making up stories. But this wasn’t anywhere else, and Adia was as honest and conscientious as a kid could be, which meant a goat really had eaten her pencil and paper. She placed her hand on Adia’s shoulder.

“Not to worry. I have some extra supplies in my jeep.” Pippa reluctantly pulled the watch out of her pocket. She glanced at the time and stuffed the watch away again. “I didn’t realize how long we’ve been sitting here. You are reading so beautifully, you made me forget. And you’re at my favorite part in the book, too. It doesn’t matter how many times I’ve read or heard the story, I still feel my heart race when Captain Hook hears the ticktock of the crocodile approaching.”

“Me, too,” Adia said. She smiled and marked her page. “Thank you for teaching me to read.”

“You’re a fast learner. You can do anything you set your mind to. I hate to leave. On my next visit, you can help me teach the little ones, then we can talk about what I mentioned last time.” Pippa sighed as she stood. This is why she hated schedules. It didn’t seem fair to end class right when a student found his or her stride. Not that this was an official class or standard school, but still. She could remember the day Adia had read her first words when she was nine. Pippa hadn’t been teaching formally back then, but she had been donating books to some of the local Maasai villages her entire childhood.

She had taught a few of the kids to read back then because she wanted to. It made her happy. But it took years for her to realize teaching was her passion.

Adia and other children had missed out on lessons when Pippa left Kenya two years ago and spent a year traveling and studying in Europe—an escape she had needed after having her heart broken. But she was glad to be back home this past year. And dedicating herself to teaching children who otherwise had no access to education was more rewarding than she ever could have imagined.

She wanted others to read their first words, too, which was why making it to the tourist lodge on schedule mattered just as much. She had an arrangement with the lodge and the guided children’s hikes she provided there allowed her to earn money for teaching supplies. She also hoped to save for a small schoolhouse—or school hut—where she’d be able to teach children from different homesteads all at once, rather than losing so much time driving long distances across the savanna.

The problem was that tourist schedules weren’t sun—or Africa-time friendly. Five minutes late and they’d start complaining. Five minutes late was nothing around here, but add an hour or two and she’d have no customers at all.

She had found that out the hard way a few weeks ago. No one had even cared about the fact that a male ostrich had decided to challenge her jeep. And then she’d inadvertently driven too close to a rhino and her calf in the brush. She’d made her escape only to hit a piece of scrap metal in the middle of nowhere that resulted in her having to change her tire. No doubt, the lodge director and tour group parents had thought she was making up stories when she’d finally arrived at the hotel.

The trumpeting of elephants in the distance shook the air as if to give her a warning that she would be running late soon. She gave Adia a hug, then quickly scanned the enkang. The place bustled with activity, from the familiar act of women grinding corn, to making beaded jewelry and continuing to repair and build their huts. The village would crumble without the tireless work the women did here. Most had never left their clan, yet they had the focus, strength, persistence and motivation that so many students and people Pippa had met during her recent year of travels lacked. People who took the opportunities they had in life for granted.

“I don’t see your father. Did you talk to him?” Pippa asked as they walked toward her jeep. She really hoped that Adia’s father wouldn’t be opposed to the girl pursuing an education in Nairobi. Adia scratched her tightly cropped hair, then fidgeted with the colorful bracelets that ran halfway to her elbows.

“No, not yet. I’ll talk to him when you are here next time. With you. Please?”

“Okay. But I don’t want to offend him. This discussion is between you. The decision is his.” There was a fine line between advocating for a kid like Adia and crossing boundaries when it came to family, expectations and culture. The fact that everyone knew Pippa around here might help a little, but upsetting the tribal leader might put a hitch in her efforts to teach others in the village. She respected the Maasai and this particular family tremendously, and offending them was the last thing she wanted to do.

“Of course,” Adia said, following her outside the enkang’s fence to where the jeep was parked. Pippa reached into a backpack on the passenger seat and pulled out another pencil and small notebook. She handed them to Adia, gave her a hug and waved as the girl hurried back to her hut.

Pippa settled behind the wheel of her jeep and looked one more time at her watch. Talk about addictive. No wonder people succumbed so easily to the power of clocks and schedules...and stress and anti-anxiety drugs. How would someone like Adia adjust to that world? Would she lose her bond with and appreciation of her culture? Was Pippa causing more harm than good?

She took a deep breath, and her stomach rumbled as she started the ignition. Her home in the Busara Elephant Research and Rescue Camp was along the way, but she didn’t have time to swing by for a bite.

She had six kids booked for the hike, and she couldn’t risk being late. There weren’t a lot of opportunities out here for her to save up. As much as she hated the outside world leaving its footprints on this majestic land, being near the Maasai Mara meant tourists hungry for a glimpse of Kenya’s Serengeti and its wonders—and that meant money.

Funny how the things that annoyed her were the very things that she relied on to achieve her goals. Balance rarely happened without sacrifice. Everything from relationships, marriage and the circle of life that surrounded her proved it. The balance and beauty of the savanna relied on both predator and prey. Death was a necessary evil, but it provided for new beginnings. It, paradoxically, gave hope. She floored the pedal and held her breath till the dust she roused was nothing but a dissipating cloud in her rearview mirror.

She was making it to Tabara Lodge on time if it killed her.