Читать книгу Don't Rhyme For The Sake of Riddlin' - Russell Myrie - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Birth of Public Enemy

ОглавлениеThe demo version of ‘Public Enemy Number One’ was recorded in December 1984, a full two years before it became their debut twelve-inch release for Def Jam. Chuck took it up to WBAU and gave it to Dr Dre who played it on his show The Operating Room. Jam Master Jay was also in the studio, and he liked what he heard. ‘It became a mainstay on WBAU, and it shut those guys up,’ Chuck says of the Play Hard Crew who inspired the record when they challenged Chuck. ‘Jay was like, “Yo, that shit is hot.”’ What happened next is subject to debate.

According to some, Jam Master Jay was the first person to play the demo of ‘Public Enemy Number One’ to Rick Rubin, who co-founded Def Jam with Russell Simmons. But other insiders insist Dr Dre did the deed. It could quite easily have been either. They were both present when the song was brought to the studio after all. Jay, a big fan of their radio show, had such enthusiasm for hip-hop that he was constantly playing the newest joints to any and everyone he came across. Naturally, Chuck still has mad love for Jam Master Jay after all these years. ‘Jay would tape every show and then take it back on tour and all that so of course it got around and “Public Enemy Number One” would be the hot song.’ It’s also entirely possible that Dre – who would himself enjoy a hit with ‘Can You Feel It’ as part of Original Concept– played it for Rick when trying to hustle his way through the door. Original Concept would go on to release their debut album Straight from the Basement of Cooley High on Def Jam.

According to Dre, he played it for Run DMC and The Beastie Boys on a tour bus while he was DJing for The Beasties. ‘I was playing them a bunch of stuff that we had from the station and this one tape stuck out. They were going, ‘This “Public Enemy Number One” record is crazy Dre, you gotta take it to Rick, you gotta take it to Rick.’ At the time I was doing the Original Concept stuff so I said, “Let me take it up there.”’

He duly passed it on to both Def Jam head honchos, but didn’t receive the response he’d hoped for. ‘I gave it to Rick Rubin and Russell Simmons. Russell threw it out the window. I put it in the deck, played it, and Russell got it and just threw it out the window. I said, “Yo man, why you throw my tape out the window?”’ While Russell obviously didn’t like it, Rick called Dre back in two days. ‘He was like, “We’re gonna sign ’em, we’re gonna sign ’em!”’ Bill Stephney, who by this time had graduated from working in promotions to become vice-president at Def Jam, insists that this is how it went down. But regardless of who played it for him first, Rubin was determined that he would sign whoever was responsible for such a groundbreaking song. Bill Stephney was in no doubt of Rick’s seriousness.

‘Rick said, “We gotta sign Chuckie D. If you don’t sign Chuckie D you’re fired!” In a typical Rick Rubin sort of way. So I’m like, “Is he gonna fire me with all this success that’s happening?” They only have like one employee: me. What kind of sense does that make?’ Despite his tactics and personal quirks, Rubin proved how ahead of his time he was. He caught on to how special ‘Public Enemy Number One’ was despite its sonic strangeness. In fact, he probably liked it more because of this quality. After all, as Chuck says, ‘You gotta understand, that shit was noise in 1987. So you can imagine like 1984–85. It was like, “What the fuck?”’ he says before recreating the sample from the JBs’ ‘Blow Your Head’ with his mouth to emphasise the point.

If you’ve heard it, it’s easy to imagine. If not, the noise is not completely dissimilar to the prolonged wail of a crying baby, albeit one with an unnaturally deep voice. But this baby has decided to hold his crying note like Bill Withers at the end of ‘Lovely Day’. Chuck had been a fan of ‘Blow Your Head’ for a long time. He originally heard the song when he attended Roosevelt Roller Rink as a teenager. ‘Let me tell you I was a rollerskating motherfucker,’ he confirms with a laugh.

The idea to loop the song came from DJs who couldn’t mix the record properly. Many DJs couldn’t extend the groove properly and weren’t mixing and blending (or back-to-backing if you prefer that term) the two copies of the same record in time anyway. There would always be the tiniest gap between the old ‘waaaaaaaaaaah’ and the new one. And as Rakim would insist in a year or two there ‘ain’t no mistakes allowed’.

At this time the term loop didn’t exist, there still weren’t any machines a producer could load a beat into. All Chuck knew was that it didn’t sound right. ‘I was like, “They need to hold that shit”.’ Determined to get it just right, the Public Enemy camp happily used the (now super old-school method) of twin cassette decks. Just as it had done with the turntable, hip-hop revolutionised the way cassette decks were used. ‘When cassette decks first came out black people took them cassette decks and made pause tapes,’ Chuck says. ‘And pause tapes was the first remix tapes.’

Significantly, ‘Public Enemy Number One’, which went through many incarnations, was the first song to feature Flavor Flav and Chuck D on a song together. Flavor opens up the song by rehashing the real conversation he had with Chuck about the Play Hard Crew coming for his neck. Then, at the end of the song, Flav praises Chuck for a job well done on some ‘that’s right, you showed ’em’-type shit. It marked the beginning of a great musical partnership, one of the greatest in music history.

However, it didn’t really matter how anxious Rick Rubin was to sign Chuckie D (he still hadn’t shaved the ‘ie’ from his rap moniker) and Spectrum (despite recording ‘Public Enemy Number One’ they were also yet to change their name). They still didn’t want to sign to Def Jam, or any label for that matter. The Spectrum massive were still very interested in emulating the success of radio personality Frankie Crocker. But they were having a hard time. ‘This is before there was an Oprah, this is before Spike Lee’s big, before Denzel’s big, no one’s really big yet,’ observes Bill Stephney. ‘The big people in the community were the radio stars.’

Not even Jam Master Jay, who stayed on their case about releasing the song, could change Chuck’s mind. Flavor remembers picking up Jay and DMC to take them to the studio one day. ‘I remember Jay telling Chuck, “Yo come on, man, why don’t you put that record out, man”. They were telling Chuck that shit for some months. Chuck was like, “Man, fuck that”. It was really Jam Master Jay and DMC that talked Chuck into doing that Def Jam shit. So right now my hat goes off to Jam Master Jay ’cos he’s really part of the start of PE. Of us being a recording group.’

But while DMC, and Jay in particular, never stopped trying to persuade Chuck that a career as a professional rapper was a good idea, it was obviously going to take something uniquely powerful to change his mind when it came to taking that leap of faith. ‘I knew it would automatically just change my whole life,’ Chuck explains. Def Jam tried to diversify their offer, giving Chuck the opportunity to write for other groups like The Beastie Boys, but he wasn’t keen on that either.

A variety of factors combined to eventually change his mind. The historic show that Run DMC played at Madison Square Garden as part of their Raising Hell tour set things in motion. Once again Bill Stephney was the main link between the Rush and Spectrum camps, but Jam Master Jay also made sure his homies were invited. Rick Rubin was hopeful that they would attend the show. Unlike the show Run DMC played in Long Beach, California, soon afterwards, the show at the Garden would be legendary for all the right reasons. This was the concert where Run famously told the 20,000-strong crowd to hold their Adidas trainers in the air prior to their performance of their historic song ‘My Adidas’. Chuck, like everyone who saw or heard about this feat, was greatly impressed. (Wily old Russell Simmons also made sure that Adidas representatives saw the breathtaking response.)

But, despite the raw power of this spectacle, the media response to the Long Beach concert may have been even more crucial. Where Run DMC’s show at the Garden had been an unqualified success, the show at the Long Beach Arena was nothing short of disastrous. Not only did the Crips and Bloods fight each other with scant regard for the concert that was supposed to be taking place, they also decided to rob and assault some concert-goers. Forty people were badly injured. The predictably hysterical media response which sought to blame Run DMC, and hip-hop by association, greatly vexed Chuck (as it did all hip-hop fans).

Away from all things Run DMC, the cold hard realities regarding the lack of opportunities open to young black men at the time also reared their ugly head. The people who would form PE had to reluctantly admit to themselves that the job in syndicated radio they hoped to win was just not realistic. Chuck realised their choices were severely limited. ‘It was sorta like the only direction that was left because they wasn’t gonna give us any shot on the radio, on professional radio in New York City. It just wasn’t that time. Regardless of our skills in that field.’ That’s when Bill Stephney, Chuck and Hank all sat down and decided that instead of just doing another single they should try to come up with a concept. ‘One of the concepts that I had obsessed about personally,’ says Bill, ‘was that we didn’t have any political rap groups at that time.’ Bill was a big fan of ‘Sandinista’ by The Clash. He wondered, ‘Can we do something like that with a rap group?’

The mid-eighties was a volatile time to be a young black man in New York. Black America as a whole was feeling the effects of the Reagan administration’s ‘trickle down’ theory. It was a good lie. They promoted the always false idea that if the rich got richer, the wealth would eventually trickle down to the masses. The citizens of New York were hit harder than most. The fast-developing crack trade that would be dissected in ‘Night of the Living Baseheads’ wasn’t helping anyone.

Caught up in the middle of all the madness, and directly affected by it, the crew would spend hours discussing these issues. ‘Other young men of our time were hanging out smoking and drinking or doing drugs, or dealing drugs,’ Bill reflects. ‘All we did was talk about music and politics till 4 or 5 o’clock in the morning.’ The idea was to direct that energy into their musical output. In this respect, they would have more in common with the punk rock movement than they would with the majority of mid-eighties rappers. This notion was irresistible to the people who would soon become PE and was the reason they eventually signed on the dotted line with Def Jam. The prospect of being able to put their politics into practice proved to be too enticing. Not even their deep-seated suspicion of the music business could deter them.

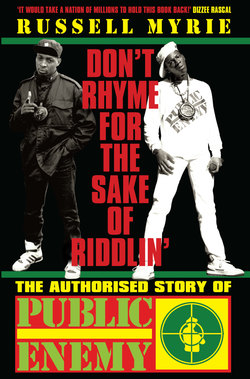

It was around this time that the graphic designer in Chuck surfaced to design the infamous PE logo. The image of a black man in the middle of a target is perhaps the most iconic logo in hip-hop history. It is certainly one of the most enduring and easily recognisable. Bill Adler, who, like everyone else, hadn’t witnessed anything like it before at Def Jam was totally nonplussed. ‘It was completely astonishing,’ the former press officer recalls. ‘Here was a group that said, “We’re going to change the consciousness of an entire culture.” Which is titanically ambitious to begin with. And they succeeded.’

PE stepped on to the scene at a time when the whole idea of black leadership was a thing of the past for America’s black youth. J Edgar Hoover’s tactics had worked: in the late sixties, soon after declaring the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense ‘Public Enemy Number One’ he famously proclaimed, ‘There will be no more black leaders, unless we create one.’ ‘Chuck’s voice sort of became that black leadership that everyone was looking for,’ claims Bill Stephney. ‘It’s almost like when you heard Chuck’s voice on record, you heard our version of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, even though he’s a rapper and it’s a rap group.’

However, once Chuck was on board, he then had to convince Def Jam that signing Flavor Flav, who had no clear role within the group, was an equally good move. Eventually, Flav recorded enough vocals on the Strong Island crew’s first album to be signed to a contract as a vocalist. But there was uncertainty about Flav at Def Jam. While some members of PE have spoken about how Russell and Rick in particular were unsure about what it was that Flavor actually did, Bill Stephney admits that he also objected. ‘I’m the one who actually thought Flavor didn’t make any sense,’ he says laughing. ‘I don’t know if Chuck or Hank speak to this, but I don’t recall Rick or Russell ever making any declaration that they didn’t want Flavor to be part of the group. I know I did. I remember having a meeting, and I’m thinking, well, “We want to do some serious political rap group, we wanna be like The Clash you know, we can’t have Flavor in the group! Are you out of your mind?”’ This point of view would dog Flav at various points of his career.

Bill Adler confirms there was considerable disquiet over Flavor’s membership in some quarters. ‘You kinda had to scratch your head even at that time and wonder, “What is he doing in this group? What does he have to do with this kind of righteous solidarity?” Political solidarity. He was a brother on the corner, you know?’ Hindsight, naturally, allows everyone to easily see how vital Flav was to proceedings. ‘And yet he was a key element in the group,’ Bill continues. ‘He was brought in by Chuck as a comic relief to Chuck himself. It was really brilliant and rather self-effacing of Chuck to do that. It demonstrated a lot of knowledge on his part. Chuck D had the sense to build a counterpart to himself and build some comic relief in the form of Flavor.’

Thankfully, it didn’t take long for the combined force of Chuck and Hank to bring Bill round. ‘Chuck explains to me, “You gotta have Flavor,” and then Hank explains it too: “You gotta have Flavor,’ cos Chuck might be too serious, so you need a balance there.” At a certain point I said, “Okay, why not, it makes sense to me, let’s just go with it.”’ Flav himself never suffered from these misgivings and was rightly confident from the jump. ‘They were getting ready to make a big mistake,’ he states on the subject. ‘But I did end up getting signed, and I became one of their biggest voices, their biggest entities. I became their most sampled voice.’

Simultaneously, with the birth of PE, Unity Force became the S1Ws. The S1s incorporated the discipline of the Nation of Islam with some of the influences of the Panther party, and sought to rid the world of the pejorative phrase ‘Third World’.

‘How can someone else define us, and call us third class?’ asks James Bomb. ‘We are the original people of this planet, so if we don’t see ourselves as First World people, then someone else is going to define us and we can’t let anyone else define who we are and what we mean to the planet earth. It’s our resources that’s fuelling the planet earth right now. You go to Africa, you’ll find the most gold, silver and diamonds. All the precious metals that make society work as it works.’

The last piece of the puzzle to slot into place was Norman Rogers, aka DJ Mellow D. Mellow D used to fill in for Spectrum gigs as and when he was needed. Keith was the original and seemingly natural choice for the group’s DJ, but quiet, dependable Norman was chosen by Chuck and Hank, probably because of those qualities.

Chuck and Hank were also responsible for creating Mellow D’s Terminator X persona. Eric Sadler describes Norman as ‘a big teddy bear, he’s really like Yogi Bear, the most lovable, naive, goofy kid that you could ever have.’ Such a personality would never fit in with PE. ‘They decided, “You know what?”’ Eric continues. ‘“Don’t speak. You’ll speak with your hands.” And that’s what he basically kinda stuck to.’ This marked the only time someone’s persona was significantly changed to fit the group. Of course, all performers perform. But this doesn’t mean they’re pretending.

Chuck and Flavor were the only people actually signed to contracts at Def Jam. Everybody else was a hired employee on a wage. Although it wasn’t a great situation, nobody was starving. And once they started gigging things gradually improved. Some years later, Terminator X got his own contract.

For his part Eric sorted a deal that was different from everyone else’s. When he was approached about working on the album he confirmed he was definitely interested but that he didn’t want to work for a pittance. But that didn’t change the fact that there wasn’t much money to go round. ‘I said, “Aiight it’s near Christmas time so I won’t charge that much, but I need to get a hundred dollars a jam,”’ he remembers telling Chuck and Hank. His work on PE’s debut album would amount to $1,200.