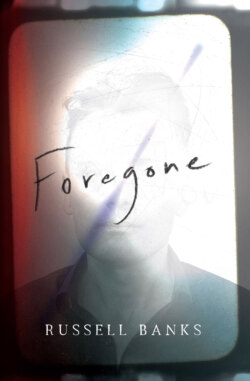

Читать книгу Foregone - Russell Banks - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

6

ОглавлениеFife wakes, ending his dream. He’s still in Richmond, he’s at the home of his in-laws. It’s morning.

He tries for a moment to remember the dream, the rules that determined its order, but can recall no more than a half dozen fading images, so gives the effort up. He tries instead to recall what’s going to happen now: living here. Leaving here. Today. Now.

Turning from his back onto his left side, he studies Alicia’s sleeping pregnant body. Beneath blankets, it lies in long mounds that churn with life. His own stringy, inert flesh, as he slowly comes awake, grows heavier and heavier, until finally, when he knows where the room is exactly and where he is located in it relative to everything else, his body, immobile beneath the blankets, weighs on his thoughts like a fallen log. One hand lies trapped beneath a hip, the other pressed against the opposite hip, as if he has caught himself while applauding his dreams.

He tries lifting his free hand, hoping that his torso will spring loose and glide easily away from this strange grasp. But the hand refuses to budge. He tries again. Nothing. Breathing heavily, he becomes suddenly aware of his protruding ankle bones and knees and the top leg pressing heavily down upon the leg beneath, both of them driving down into the mattress. Then his shoulders, and the weight of his chest. Even his skull presses downward, as if it’s been carved from a block of stone and attached loosely to the still larger block of stone that is his body from his shoulders to his large, flat feet. A hard wind or a gang of vandals shoved him off his pedestal and left him to lie here on his side, seeping slowly into the cold soil, silent and motionless.

He groans, and a hand shoots up beneath the sheet that covers him. He slides one leg off the other and is able to free the hand that has been trapped by his hip. He feels his face wrinkle and knows that he is grimacing. His body still weighs on the bed like a fallen statue. It takes all his strength, but he manages to push and shove it from one place on the bed to another. Concentrating his efforts, he flops his body over onto its back again. Then onto its other side. Until he finds himself staring away from his wife toward the window.

Light filtering through membranes, he thinks. Why doesn’t the darkness of the room flow the other way? Why doesn’t the darkness chase the light? Heat chases cold.

He steps from the bed, pushing his naked limbs slowly ahead of him, and dresses, covering his body with the clothes he laid neatly across the chair by the window last night after packing, one item folded neatly on top of the other. His travelling clothes—socks and underwear, grey flannel slacks, white shirt, maroon foulard necktie, navy-blue blazer, all of it mail-ordered from Brooks Brothers, chosen for him by Alicia, menswear brand discrimination, learned from her father. He stuffs his pockets with the loose items on top of the dresser: wallet, change. He straps on his wristwatch.

A checklist: suitcase packed; all necessary papers in briefcase; two novels and a book of Hardy’s poems in briefcase; ticket in jacket pocket; cash in wallet. Anything else? Chequebook? Yes. The bank cheque? In briefcase. Take another look, be sure. Yes, it’s there.

Are you all ready to leave me and your little babies, born and unborn?

He turns, surprised and embarrassed. While he patted pockets and tapped suitcase and briefcase, Alicia has been watching him.

Not quite, he says. No. I haven’t had breakfast yet. Go back to sleep. I’ll come up and say goodbye before I go.

She yawns like a cat, her entire body tightening into a thick arch. Anybody else up yet?

Yeah, I think your mother. And Susannah. I don’t know if Cornel’s awake or not. You sure your mother doesn’t mind taking me to the airport?

Forget it, sweetie. It’s her thing, taking people to airports and waving goodbye to them. She loves it.

What about Cornel? He may cry, Fife says.

Oh, let him sleep. I’ll explain it to him later on. If he’s awake and up, though, you might’s well let him ride out to the airport with you and Mummy and say goodbye to you. She’ll enjoy consoling him on the way back.

He smiles down at her and leaves the room, taking care to close the door quietly behind him, as if she’s already fallen back to sleep. His body descends the carpeted stairs like water down a hillside stream, bumpity-bumpity-bump.

Seated side by side at the kitchen worktable, Cornel and his grandmother eat together. The two, grandmother and grandchild, have agreed, without ever saying, that both enjoy meals more when the child refuses to eat until coaxed to do so by the grandmother. Cornel’s middle name is Leonard, and no one in the family uses it, except on legal documents.

Fife stands unseen at the kitchen door and listens with low-level irritation as his son coaxes the grandmother to coax him to eat more oatmeal. Fife is unsure why he’s irritated. Come on, Cornel, she chirps. Come on now, honey, just two more big spoonfuls. That’s the sweet boy. There now, that wasn’t difficult, was it, honey?

He enters the breakfast room adjacent to the kitchen, and Susannah looks over and sings, Good morning, Mr. Fife. He cringes and sits at the table.

H’lo, Susannah, he says, rushing to get it over with. No eggs or anything this morning, please. Just coffee and juice.

How about some beaten biscuits, Mr. Fife? They awful good, especially since you going on a long trip today.

Yeah, fine.

Good morning, Leo, his mother-in-law calls from the kitchen.

Good morning, Jessie. Hey, Cornel, say good morning to me.

Hello, Daddy.

Jessie, if you don’t mind, I’d just as soon take a cab out to the airport. There’s no need for you to drive all the way out there and back.

No, she says. He will not call a taxi. The drive to Byrd Field is a pleasant one. And there is nothing she’d prefer this beautiful morning than to drive across Richmond in the company of her son-in-law and grandson. It’s spring, she announces. March thirty-first. And the city is too beautiful for words. Everything is suddenly blooming today, and she wants Cornel to see it all. You want to see the flowers, don’t you, honey?

Where’s Benjamin? Fife asks, suddenly aware of his father-in-law’s absence.

He left early for the club. He said to wish you well. Oh, here’s the paper, she says. Don’t get up, I’ll bring it to you. Sit still.

She strolls into the breakfast room and hands him the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

You haven’t much time, she warns. Do you want to use Benjamin’s electric shaver?

His hand goes to his cheek. He should have shaved last night, as he planned. Or else gotten up earlier this morning. He remembers Alicia’s imitation of her father.

Alicia, honey, the man’s unstable.

Then in her own voice: Of course, Daddy. What interesting twenty-two-year-old man isn’t, for God’s sake? I wouldn’t want him stable.

But, Alicia, he’s a college dropout. Not able to get himself a college degree.

He will, she answers. Did you and Uncle Jackson finish college, Daddy?

Causing her father to turn away from her, to stare out the library window at his gardens while easing sideways toward the liquor cabinet. The boy doesn’t have a penny. He doesn’t have a red cent, and his family doesn’t, either.

He will if he marries me. She lights a cigarette and casually seats herself on a window ledge.

Facing the bar, he pours a double shot of bourbon, downs it. But how’s it going to look?

To whom?

Well, to your friends, for instance. And to the rest of the family. To your own children someday. I imagine you do plan on having children. How will they explain it to their friends? Tell me that.

Alicia begins to laugh.

You laugh, but you’ll see I’m right. I knew it the minute I laid eyes on him.

Alicia reported the exchange to Fife shortly after it occurred. Fife believes that was the moment when Benjamin decided to hire a private detective to check out the young man’s story, and a month later he learned that Leonard Fife had already been married once and divorced. Alicia had known it all along, but had not told her parents or anyone else. When her father put the detective’s report in front of her, Alicia laughed, and eventually so did they all, long afterwards—Fife, Jessie, even Benjamin himself. Alicia knew all about that brief, misbegotten marriage. It is not at all unusual for a sensitive, honourable young man from his background to marry his first serious girlfriend, only to learn quickly that it was a mistake. What is unusual, Daddy, is that he had the grace to call it a mistake and undo it.

In spite of the laughter and the slowly accumulated respect and trust, Fife has not forgotten the early anger, fear, and distrust. Every time he looks into a mirror and begins to shave, his razor poised high and tight to his right earlobe, he remembers, and for a second he tries to see himself as he must have looked to Benjamin back then, when he came to Richmond the first time, driving south from Boston with Alicia in her Morris Minor to meet her parents, a tall, skinny, hairy youth with a complicated, slightly sordid past and nothing more to recommend him than his plans for an even more complicated and only slightly less sordid future. He feels toward that entire period the way he would toward a birthmark—embarrassed, yet blameless.

Well, Jessie repeats, do you want to use Benjamin’s shaver?

If I have time, maybe I’ll step into a barbershop in Washington. There’s an hour and a half layover between planes. It’ll give me something to do.

All right then, she says and spins and exits into the kitchen in a swirl of yellow sundress and frozen smile.

He drinks his orange juice and coffee and munches on buttered, oven-warmed beaten biscuits, glancing across the front page of the Times-Dispatch. Vice President Hubert Humphrey is in town. Dr. Martin Luther King’s poor people’s march is unnecessary, claims Humphrey. Any grievances Dr. King might wish to air can be heard effectively by top government officials without marches or demonstrations. On the war in Vietnam, Humphrey says the Johnson-Humphrey administration is open to peace negotiations if there’s even the slightest indication that the enemy is willing to negotiate in good faith. The real peace candidate in these primaries is Lyndon B. Johnson, he says. Farther down, a box announces that tonight at nine the peace-loving President Johnson will tell the country by radio and TV that he’s ordering an increase in troops and spending for the war. Fife will be at Stanley Reinhart’s by then. They’ll probably have to watch it, with Stanley bellowing insults at Johnson. Firebombs went off yesterday in New York at Macy’s, Bloomingdale’s, Gimbel’s, and Klein’s, and a dynamite blast shattered thirty windows at New York’s major Selective Service induction centre.

He peers out the window of the breakfast room at a corner of the large yard, the manicured lawns, a luminous springtime shade of green already, and the blossoming dogwood and Judas trees. Through the trees and beyond he can glimpse slate-coloured scraps of the James River. The yardman, as they call him, comes slowly into view. Fife thinks his name is Joseph or Calvin or Roger. He carries a small fireplace shovel and a metal dustpan. Crossing the yard to the far corner where the lawn droops to meet a clutch of shiny dark-green magnolia trees, he stops, bends down slowly, carefully shovels a small lump of dog turd into his dustpan. Then he stands and resumes his search, passing out of Fife’s view to the other side of the house.

Your plane leaves in little over an hour, Leo! Jessie calls. We better leave for the airport in five, to be safe. Okay?

Can I go, Daddy? Cornel asks, more from a desire to be polite than a need for his father’s permission. The boy’s mother and grandmother have both reassured him that he can help take his daddy to the airport.

Yes, you can go with me, Fife says uselessly. As far as the airport, anyhow. He finishes his coffee and gets up from the table. Then you’ll have to come back here with Meema, okay?

Okay, Cornel says quietly and lapses into silence.

Is he afraid? Fife wonders. Or does he assume with the others that after a week away, Fife will be coming back here? The boy doesn’t realize that Vermont is a place distinct from this place, a thousand miles away. Once there, his father, if he chooses, will be free not to return. Cornel believes that his father has no such choice. Or desire. He believes that his father will simply disappear from his sight for seven days and nights, only to reappear suddenly, as if by magic, waving from the doorway of an airplane. Waving neither hello nor goodbye, but, Here I am again.

So why should he be afraid?

In their bedroom Fife leans down in the soft grey light to kiss his wife’s sleeping face, and her eyes flutter open, like a bird taking flight.

You look very beautiful. I’ll miss you, he says. Are you feeling all right?

She smiles. Have you got everything you’ll need?

Yes. He kisses her on the lips once and then on each cheek.

Will you be able to call me tonight?

From Reinhart’s, yes. I’ll call, don’t worry.

Is Cornel going with you?

Just to the airport.

That’s what I mean, silly. Good. I’m glad.

Why?

I don’t know. She shrugs. I guess because it’ll make it easier for me. To explain why you’re not here for the next week. He’s going to miss you, you know. He’s used to having you around all the time.

I’m his only father.

He’s your only son. At the moment, anyhow. Do you want to talk more about last night? About Daddy and Uncle Jackson and Doctor Todd’s?

Tonight. On the phone.

Yes, of course. I didn’t mean now.

Right. Listen, I’ve got to get going or I’ll miss the plane. I love you, take care of yourself. He waves casually as he leaves the room, his suitcase dangling from his left hand, his briefcase stuck under his arm. He shuts the bedroom door on her, then hears her call.

Leo! Did you forget to shave?

Jessie and Cornel are already seated in the car, waiting for him. Fife flings his two bags ahead of him and climbs heavily into the back seat. His son looks around from the front and gently smiles. Can I get a Popsicle? he says, this time asking sincerely for permission. A Creamsicle! Can I get a Creamsicle?

I don’t know, Fife answers. It’s too early. There isn’t enough time.

What flavour, sweetie? Jessie asks.

Orange on the outside, vanilla on the inside!

Fine, dear. We’ll stop and get you one after we take Daddy to the airport. We’ll have more time then. Sit down on the seat now, sweetie. It’s dangerous to stand while the car’s moving.

She backs the green Mercedes out of the garage and heads it down the long, gently curving driveway to the street.

Fife lets his weight sink into the upholstered seat behind and beneath him, and his body once again feels heavy to him, a solid mass yanking him deeper into the seat. He tries to raise one hand to lower the window and discovers that he can barely lift it off his lap. His feet press themselves against the carpeted floor, and his thighs crush the cushioning beneath them. He slowly turns his head to the right and finds that he’s looking out the car window at nothing but blurs and flashes of coloured light that turn out to be large brick homes with impeccable lawns, and in front of them and on either side, chalk white and rosy pink clumps of fruit cherry and flowering trees. There are gardenias, dogwoods, drooping willow trees, tulips and deep pink Judas trees, all coming abundantly to life and sweeping past him, as if in flight.

To stop his flight, he runs through his schedule. He will leave Richmond at 9:15 a.m. and arrive in Washington at 10:03. Then, changing from Piedmont to Eastern Airlines, he’ll take off from Washington at 11:30 and arrive in Boston at 1:20 p.m. He’ll rent a car and leave Boston before 2:00 for Reinhart’s home in Plainfield, Vermont, which will let him have dinner that evening with Stanley and his wife, Gloria. The business of completing the purchase of the house can begin in earnest tomorrow morning. He recites this as if memorizing it.

Jessie says, We won’t get out of the car, Leo. It’ll be easier to say goodbye here. For C-O-R-N-E-L. Okay?

Sure.

Have a pleasant flight, Leonard. And call us tonight when you get in.

Call us. Not call me, not call Alicia, your wife, or Cornel, your child. Call us. The family, Leonard.

Fife looks out the car window and sees that they have arrived at the entrance of the terminal. A young, moustachioed Black porter stands next to the glass door of the terminal, peering over at the Mercedes, waiting for the occupants to indicate whether they’ll need his services. Fife leans forward from the back seat and kisses Jessie on her dry cheek, surprised to find it powdered and smelling heavily of perfume, the same Alicia uses, Chanel No. 5. I’ll call tonight from Reinhart’s.

Then his son. He puts his arm around the boy’s tiny shoulders, kisses him on the cheek. He feels strangely self-conscious, as if Cornel were someone else’s child, a stranger’s, and it confuses him. Be a good boy. And take care of your mother, he adds.

He is mortified by his own words. The tinny, insincere sound of his voice repulses him even more than the words. Well … goodbye. I’ll call in tonight from Reinhart’s, he says again. He grabs his suitcase and briefcase and scrambles clumsily from the vehicle.

Have a nice flight! Jessie calls.

He slams the door. He shakes the porter off. Waving a hand at the car, he turns, and he is headed for the glass door when he hears Cornel start to cry and then to sob loudly. Looking back over his shoulder, he sees his son’s small, round face go soft. Fife wants to turn back and comfort the child. He looks away from him and lurches for the door. The porter’s hand snakes in front of his own and swings the door open for him. Fife passes through and into the terminal.

As he passes, the porter chuckles. That little boy don’t want his daddy to leave.

Fife keeps on moving.